TOWARDS A NEW MAP OF THE MIDDLE EAST – TREND ANALYSIS

Coming after the outbreak of the Arab Spring and the aftermath of the Iraq War, the current events in Syria, including Turkey’s involvement, and the perspective of a U.S./Israel military action against Iran, are more and more telling signs that long-established geopolitical landmarks in the Middle East are beginning to change.

In the case of Syria, one of the possible outcomes after the eventual toppling of the Assad regime would be the disintegration of the country, since many analysts believe that the Syrian regime will never be able to reclaim the Kurdish areas to its control. That would result in an Alawite-dominated state, eventually recognized by Russia (following the precedent already employed in 2008 with South Ossetia and Abkhazia), and a Syrian Kurdish region (already abandoned by the Assad government) that would fight to obtain a level of autonomy, as well as the right to pursue closer relations with Iraqi Kurdistan, leading to the emergence of a separate and united Kurdish state.

In the case of Iraq, just as South Sudan separated from Sudan after enjoying several years of autonomy, Iraqi Kurdistan could try to negotiate a separation from Iraq and then unite with a Syrian Kurdish entity. A collapse of Syria accompanied by a Kurdish secession from Iraq, would also sign the disappearance of Iraq in its current configuration. This would also completely change the nature of the Kurdish insurgency inside of Turkey itself, since the Kurds in Turkey might push to transform the Turkish Republic into a Turkish-Kurdish federation, and in so doing absorb the Syrian and Iraqi Kurdish entities.

In the case of Iran, most of the analysts that oppose the idea of a U.S. strike against Tehran point that such a war might end with another disintegration process, with a Kurdish enclave in Iran’s northwest tied to Iraqi Kurdistan, Iran’s Azeri north drifting toward Azerbaijan, and a Baluchi enclave in the south linked to Pakistan’s largest province, Baluchistan, leaving Iran only with the ancient territory of Persia.

More pessimist analysts see Syria breaking apart into Sunni and Alawite, Arab, Kurd and Druze, Christian and Muslim, Islamist and secular; Afghanistan dissolving into Tajik and Uzbek in the north, Hazara in the center, and Pashtun in the south and east; Iraq losing Kurdistan and reverting to civil-sectarian war. Finally, a U.S. defeat of Iran could bring to power revanchists and half of the population that is Arab, Baluch, Kurd, and Azeri would try to break away.

The events in the Middle East are seen as a challenge to the territorial order that followed the Sykes-Picot agreement[1] between Britain and France. That agreement, as refined in the early 1920s, divided the Middle East according to boundary lines that persist today, dividing formerly Ottoman territory into the countries of Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, and drawing modern Turkey’s frontiers. As a result, the Kurdish hope for self determination was denied, leading to intermittent rounds of guerrilla warfare and confrontation. Lebanon was an artificial entity that became increasingly war torn and fragile. Israel, the Palestinian territories and Jordan have all had tumultuous histories. Syria resented the loss of Lebanon and its mix of religious and ethnic groups never generated a healthy political or civil society. Iraq is also seen as being on the way to become different entities.

On the other hand, the foreign powers seem to have lost the ability to prop up local governments they had in the 1950s, and subsequently, the domestic despots have failed, so more and more analysts are convinced that the “Sykes-Picot states” (Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq) might not survive for long in their present boundaries.

1. “New Maps” for the Middle East

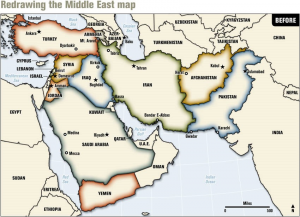

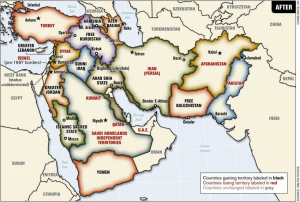

In this changing context, many analysts are beginning to have a new look at the so-called “New Middle East Map”, drawn by U.S. military intelligence analyst Ralph Peters[2] and published in the American Armed Forces Journal in June 2006. Although at the moment it created a widespread criticism that prompted the White House to officially distance itself from it, the analysts of the current-day events cannot help to notice that it shows quite accurately what may actually happen in the near future.

The map depicts Iraq as being split into three distinct nations: the “Free Kurdistan” in northern Iraq, “Sunni Iraq” in the south-western sector and “Shia Iraq” in the south-eastern sector, with Basra as the capital. The new “Arab Shia State” in south-eastern Iraq goes down along the Persian Gulf to Qatar, taking also land away from Saudi Arabia.

The new country it shows, Kurdistan, is the result of both Turkey and Iran relinquishing a significant part of territory. Turkey would be forced to give up some land on its Eastern border with Iraq, while Iran will have to forfeit some of its land on the Western border with Iraq.

Jordan would expand till the Red Sea, at the expense of Saudi Arabia, which would give land from all parts: on the Red Sea to Jordan, on the Persian Gulf to the “Iraq Shia State” and in the south to Yemen. If such a map is to be implemented, Saudi Arabia will be stripped of almost all the access to the ocean. Moreover, it will lose the management and control over the Islamic Sacred Sites. The Jewish state is going to be forced to retreat back to their pre-1967 borders so the Palestinians can be given their own state, and a “Free Baluchistan” would be carved almost completely out of Iran.

Ralph Peters’ map was considered to be based on several other maps, including older maps of potential boundaries in the Middle East extending back to the era of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and World War I. Although it was officially said that it did not reflect Pentagon doctrine, the map has been used in a training program at NATO’s Defense College for senior military officers and probably in U.S. military planning circles. According to Turkish press releases, on September 15, 2006 the map of the “New Middle East” was displayed in NATO’s Military College in Rome, Italy and it generated outrage among the Turkish officers who saw their country portioned and segmented. It was assumed that the map received some form of approval from the U.S. National War Academy before it was unveiled in front of NATO officers in Rome.

Since Ralph Peters’ books on strategy were seen as being influential in U.S. government and military circles, the “new map” project is considered by some analysts as revealing, in fact, what U.S. strategic planners had been anticipated quite earlier for the Middle East.

Before Ralph Peters’ “New Map”: the “Greater Middle East”

One of the first outlines of possible changes of the borders in the Middle and Near East was a “New Greater Middle East” concept exposed by Geoffrey Kemp and Robert Harkavy[3] in 1997. After 9/11 2001, the “redrawing” of the Middle East came forward on the agenda, with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s strategy to overthrow Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and then topple the regimes in Syria, Iran and four other Middle East countries. A report by Douglas Feith, former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, emphasized that the idea to redraw the Middle East map by military means was supported by the entire U.S. military establishment. In his memoirs[4], Feith included fragments of the report sent by Rumsfeld to President George Bush on September 30, 2001, calling for focusing on bringing to power “new regimes” in some Arab countries. Also, U.S. retired General Wesley Clark mentioned in his memoirs[5] that a Defense Department list of countries where governments were to be overthrown included Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Libya and Somalia.

A “Greater Middle East Project” was announced by George W. Bush on November 6, 2003 before the National Endowment for Democracy. According to Bush, the occupation of Iraq was to be the first stage of a long struggle for “the victory of democracy” in the Greater Middle East. The list of authors of the concept included Henry Kissinger, Dick Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz (most of them members of the neo-conservative “Project for the New American Century” – PNAC[6]). That was considered as aiming, in fact, to take under control the resources of Africa and Middle East in order to block economic growth in China and Russia, thus taking the whole of Eurasia under control.

Before G8 summit in June 2004 in Sea Island, Georgia, Washington published a working document called “Partnership for Progress and a Common Future with the Region of the Broader Middle East and North Africa”, but failed to receive support for the U.S. idea of democratization in the Middle East.

Later on, the concept of a “New Middle East” was introduced in June 2006 in Tel Aviv by U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (who was credited by the Western media for coining the term) in replacement of the older and more imposing term, the “Greater Middle East”. It coincided with the inauguration of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Oil Terminal in the Eastern Mediterranean.

It was also used by the U.S. Secretary of State and the Israeli Prime Minister during the Israeli siege of Lebanon (July 2006), when they informed the international media that a project for a “New Middle East” was being launched from Lebanon. It was considered at that moment as a confirmation of the existence of an Anglo-American-Israeli “military roadmap” in the Middle East, aimed to generate instability and violence that might be used by the United States, Britain, and Israel to redraw the map of the Middle East in accordance with their geo-strategic interests.

In the 90ies: Brzezinski’s “Eurasian Balkans”

The “New Middle East” concept was also seen as an attempt to achieve, in time, a so-called “balkanization and finlandization” of the area, also seeking to extend the U.S. influence into the former Soviet Union and the ex-Soviet Republics of Central Asia. Such a theory was exposed in the late 90ies by Zbigniew Brzezinski, former U.S. National Security Advisor[7], who considered that the modern Middle East was a control lever of an area he called the “Eurasian Balkans”. The Eurasian Balkans would be consisting of the Caucasus (Georgia, the Republic of Azerbaijan, and Armenia) and Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan,Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan) and to some extent Iran and Turkey. According to Brzezinski, both Turkey and Iran, the two most powerful states of the “Eurasian Balkans”, are “potentially vulnerable to internal ethnic conflicts [balkanization]”andthat, “if either or both of them were to be destabilized, the internal problems of the region would become unmanageable”. The “Eurasian Balkans” are “truly reminiscent of the older, more familiar Balkans of southeastern Europe: not only are its political entities unstable but they tempt and invite the intrusion of more powerful neighbors, each of whom is determined to oppose the region’s domination by another”. Brzezinski called it a “combination of a power vacuum and power suction”, that was important for at least three of the more powerful neighbors, namely, Russia, Turkey, and Iran, with China also signaling an increasing political interest in the region.

Similar to the oilfields’ map

The former U.S. National Security Advisor also pointed that the importance of the “Eurasian Balkans” is above all economic, since the region has “an enormous concentration of natural gas and oil reserves, in addition to important minerals, including gold” and “estimates by the U.S. Department of Energy anticipate that world demand will rise by more than 50 percent between 1993 and 2015”.

In this context, analysts compared the “new Middle East” map with the maps of the oil fields in the area, finding that dividing up Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia would allow the consolidation of most of the region’s oil into a new country and thus remove control over the oil from governments based in Baghdad, Tehran and Riyadh. In the case of Iraq, by splitting it into three new states, most of its oil would be concentrated in the Shia and Kurdish regions. In the case of Saudi Arabia, its main oil fields are in the east, along the Persian Gulf, and the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina are in the west. This might have been the reason for Saudi Arabia’s division into two countries – one with the holy cities but without oil, the other without holy cities but with oil fields. As for Iran, its oil is mostly in the western provinces along the Persian/Arabian Gulf, inhabited by Arab population, so the proposal for a new “Arab Shia State” along the northern Persian/Arabian Gulf would separate the bulk of the oil from Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

2. The “New Map” in the making: towards a Kurdish state entity

Most of the analysts of the region note that one of the most visible effects of the “Arab Spring” of 2011 and the civil war in Syria was the intensifying efforts of the Kurdish minorities in Syria and Iran, as well as Iraq and Turkey to use in their interest the upheavals in the region, in what is increasingly referred to as “the Kurdish Spring” (to be discussed later on).

The uncertainties faced by the states with Kurdish minorities have already allowed Kurds to grasp unprecedented autonomy, first in Iraq and recently in Syria. Kurds hope that the crisis of the “Sykes-Picot states” (and the changes in Turkey) offer them new chances for a state of their own, if not the full “Greater Kurdistan”, at least a small state in northern Iraq and Syria, with ties to Turkey. Moreover, the confrontation between Iran and the West offers them also hope for expansion into Iranian Kurdistan.

Analysts draw analogies between the rising Kurdish wave and the Tuareg wave in North Africa and the western Sahel. The Tuareg rising has already destroyed the territorial integrity and political order of one state, Mali, creating the state of Azawad, and threatens others. Another analogy comes from the emergence of the new states of South Sudan, in July 2011, and Azawad, in April 2012, which changed the old colonial borders.

The Kurds of Syria are demanding a federal system in which they would gain significant autonomy in a post-Assad Syria. The Kurds of Turkey are pressing for what they call democratic autonomy. The Kurds of Iran are also pressing on the local government for rights. The most important are the Kurds of Iraq, who managed – after their success in the early 1990ies – the establishment of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which is considered a de facto Kurdish state. It is to the KRG experience that Iranian, Syrian and Turkish Kurds increasingly look for lessons and guidance.

Recently, Iraqi Kurdistan’s president Massoud Barzani admitted that KRG was training Kurdish-Syrian fighters who will be defending “Kurdish territory”. The territory that was practically abandoned by the Assad government began to be jointly ruled by the People’s Council of Syrian Kurdistan, a body resulting of an arrangement between Kurdish-Syrian groups supervised by Barzani. KRG also supports the militant Kurdish-Iranian group Party of Free Life of Iranian Kurdistan (Partiya Jiyana Azad a Kurdistane – PJAK), formed in 2004, that has operational bases on the territory of the Kurdish Regional Government.

According to KRG sources, in the near future, the UN Security Council will allocate a special session to discuss the Kurdish statehood topic in its annual meeting, and a Kurdish independent state will come into existence by 2015.

3.The Kurdish problem

The area known as Kurdistan is estimated between 190,000 km² (by Encyclopædia Britannica) and 390,000 km² (according to the Encyclopædia of Islam that adds 190,000 km² in Turkey – nearly a third of its territory –, 125,000 km² in Iran, 65,000 km² in Iraq and 12,000 km² in Syria, totaling 392,000 km²), including parts of northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and small portions of Armenia, with an estimated population of 25 – 30 million people, having their own language, culture and national identity.

Kurdish populations are also to be found in the Caucasus area, the Middle East, in Western Europe and Post-Soviet countries. In the 1920ies there was a short-living Kurdish Autonomous Province in Soviet Azerbaijan and during the Stalinist regime, the major part of the Kurdish population in the Caucasian region was deported to Central Asia and Siberia that became the Kurdish communities in Kazakhstan, Siberia and Kyrgyzstan.

If the Palestinians are more often proclaimed as a “nation without a state”, the Kurds, who outnumber the Palestinians by a factor of five, are the most populous such nation in the Middle East.

Kurdistan’s territorial division has its origins in the Sykes-Picot Agreement, according to which Kurdistan was no longer the unofficial buffer between the Ottoman and Persian Empires, but a region divided between several new nations (Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Persia). However, neither the British nor the growing Kemalist Turkish government wished to see an independent Kurdistan, especially one able to defend itself.

In mainly all the countries with a Kurdish minority, the authorities had to deal and are still facing calls and actions (many of them violent) for autonomy and even independence. Kurdish nationalists seek to create an independent nation-state consisting of some or all of the areas with Kurdish majority, while others campaign for greater Kurdish autonomy within the existing national boundaries. Kurdish autonomy is recognized in Iraq and there is a province named Kurdistan in Iran, but without self-rule.

The so-called “Kurdish problem” refers to the separatist and/or autonomy-seeking activities of the Kurds, including those aimed to establish a Kurdish nation state. Sometimes they have been encouraged by the global powers with interests in the region.

Turkey

In Turkey, the Kurdish separatist movements began with the incorporation into the Ottoman Empire (later the Turkish state) of the Kurdish-inhabited regions of eastern Anatolia. That resulted in a long-running conflict, with several major Kurdish rebellions, including the Koçkiri rebellion of 1920, then successive insurrection under the Turkish state, including the 1924 Sheikh Said Rebellion, the Republic of Ararat in 1927, and the 1937 Dersim Rebellion, all put down by the authorities. The region was declared a closed military area from which foreigners were banned between 1925 and 1965. In 1983, the Kurdish provinces were placed under martial law in response to the activities of the militant separatist organization, the Kurdistan Workers Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan – PKK).

The PKKwas founded on 27 November 1978 and was led by Abdullah Öcalan. Since the early 80ies, it has been fighting for an autonomous Kurdistan and greater cultural and political rights. The PKK’s ideology was originally a fusion of revolutionary socialism and nationalism. The PKK is listed as a terrorist organization by a number of states and organizations, including the United States and the European Union.

As of 1994, the PKK was estimated to have between 10,000 and 15,000 fighters, (of which 5,000 to 6,000 inside Turkey and the rest in neighboring countries), as well as 60,000 to 70,000 part-time guerillas. In 2004, the Turkish government estimated the amount of PKK fighters at approximately 4,000 to 5,000, of which 3,000 to 3,500 were located in northern Iraq. By 2007, the number was said to have increased to more than 7,000. Official PKK number is declared to be between 7,000 and 8,000 fighters, 30 to 40% in Iraq, and the rest in Turkey where they were backed by an additional 20,000 part-time guerillas. High estimates put the number of active PKK fighters at 10,000.

Since its creation, the PKK evolved and was able to adapt to the changing local and international situation, which is seen as the main factor in its survival. It gradually grew from a handful of political students to a dynamic organization, and became part of the target on the “War on Terrorism”. After the 1980 coup in Turkey, the organization restructured itself and moved to Syria between 1980 and 1984.

A full-scale PKK-led insurgency began on August 15, 1984 when the PKK announced a Kurdish uprising, and lasted until September 1, 1999 when the PKK declared a unilateral cease-fire. The PKK shifted its activities to include urban warfare and terrorist attacks in other countries, between 1993 and 1995 and 1996 to 1999. Also from 1984, the PKK started using training camps located in France and launched attacks against governmental installations. It moved to a less centralized form, taking up operations in a variety of European and Middle Eastern countries, especially Germany and France and attacking civilian and military targets in Turkey and various other countries.

In the early 90’s, in the context of the establishing of the “no-fly”, practically independent zones in Iraqi Kurdistan, the PKK used them as a base to launch attacks against Turkey, which responded with military operations in 1995 and 1997.

Following an international campaign by the U.S., Israel, Greece, UK and Italy, PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan was captured by CIA agents in Kenya on February 15, 1999, and turned over to the Turkish authorities. After the trial, he was sentenced to death, but this sentence was commuted to lifelong aggravated imprisonment when the death penalty was abolished in Turkey in August 2002.

After Abdullah Öcalan’s imprisonment, the PKK unilaterally declared a peace initiative in 1999, but the armed conflict was resumed on June 1, 2004, when the PKK declared an end to its cease-fire, claiming that the Turkish government was ignoring their calls for negotiations and was still attacking their forces. Lacking a state sponsor or the kind of manpower they had in the 90s, the PKK adopted new tactics, by reducing the size of its field units from 15–20 to 6–8 militants, avoiding direct confrontations and relying more on the hit and run tactics. Another change in PKK-tactics was that the organization no longer attempted to control any territory, even after dark. From 2006, the violent clashes increased in number and intensity, with resumption of large-scale hostilities.

In 2009, a “Kurdish initiative” was launched by the Turkish government that was interested in joining the European Union. The initiative included plans to rename Kurdish villages which had been given Turkish names, expand scope of freedom of expression, restore Turkish citizenship to Kurdish refugees, strengthen the local governments and a partial amnesty for PKK fighters. However, it was practically ended after the pro-Kurdish Democratic Society Party (DTP)[8], that had won the 2009 local elections in the South East, was banned by the Turkish constitutional court on 11 December 2009 and its leaders were trialed for terrorism.

The violent clashes increased again and, according to analysts, 2011 was one of the bloodiest years in recent history of the Kurdish – Turkish conflict. In summer 2012, the conflict with the PKK increased again in violence, in parallel with the Syrian Civil War, since the regime of Bashar al-Assad ceded control of several Kurdish cities in Syria to the PKK and the Turkish foreign minister accused the Assad government of arming the group.

On the other hand, The PKK also developed a new strategy, trying to spread a Palestinian-style “intifada” movement, known as “Serhildan” (“uprising”). Within the framework of civil disobedience, it followed a strategy of increasing tension by bringing security forces face-to-face with the people. More weight was placed on city structures, with the aim to create a paramilitary organization strengthened in its capacity to carry out normal daily obligations in city neighborhoods, to provide all sorts of financial and spiritual help, and to act according to the wishes of the organization. Some experts note that the urban organization’s power has now surpassed that of the organization in the mountains.

Iran

In Iran, the Kurdish separatism resulted in an ongoing dispute between the Kurdish opposition in Western Iran and the governments of Iran, lasting since the emergence of Pahlavi Reza Shah in 1918. Better known is the Simko Shikak tribal revolt, finally defeated by central government in 1926, while another Kurdish tribal revolt was put down in 1931.

According to some historians, the organized Kurdish separatism began with the creation of the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI) that managed to establish, for a short time, a “Republic of Kurdistan”, also known as the “Republic of Mahabad” (after its capital), supported by the Soviet Union that intended to use in its own interest the Kurdish struggle against the monarchies of Iran and Iraq.

The “Republic of Mahabad” was crushed following a pact signed by the Iranian central government and the Soviet Union, after which the Iranian army launched a vast offensive into the region. More than a decade later, KDPI supported other violent tribal uprisings through the 1960s. A Kurdish rebellion was also put down in 1966-1967. One of the most violent episodes of the conflict was the 1979 Kurdish rebellion, crushed after a large scale offensive in spring 1980 by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. By late 1980, the Iranian regular forces and the Revolutionary Guard ousted the Kurdish rebels from their strongholds, but the clashes in the area went on as late as 1983. The KDPI insurgence surged again in the early 1990s, escalating because of the assassination of the KDPI leader. The conflict gradually faded with the election of the Mohammad Khatami government in 1997.

Kurdish separatism in Iran re-emerged in 2004 with the still ongoing conflict with the secessionist Kurdish guerrilla group Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan (PJAK), closely linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party in Turkey (PKK). According to founding members of PJAK, the group began in Iran around 1997 as an entirely peaceful, student-based, human rights movement. According to other sources, members of the PKK founded the PJAK in 2004, as an Iranian equivalent to their insurgency against the Turkish government. PJAK has a similar goal as PKK, to establish an autonomous Kurdish region within the state.

After a series of government crackdowns against Kurdish activists and intellectuals, the group’s leadership moved to Iraqi Kurdistan in 1999 and settled in the area controlled by the PKK, close to the border. PJAK adopted many of the political ideas and military strategies of jailed PKK leader Abdullah Őcalan, and evolved from a civil rights movement to a multi-directional independence movement, aided by the transfer of many seasoned PKK fighters of Iranian origin into PJAK. The clashes continued even after the cease-fire that was declared in summer 2011, and are still ongoing.

PJAK’s military operations are believed to be funded by Kurdish immigrant communities in Europe and Kurdish businessmen in Iran. In 2006, there were allegations that the United States and Israel secretly supported PJAK, since PJAK operates and is based in Iraqi territory, which is under the control of the U.S.- supported Kurdistan Regional Government, formed after the main Iraqi Kurdish parties cooperated with the U.S.-led coalition to overthrow Saddam Hussein.

On April 18, 2006, U.S. Congressman Dennis Kucinich sent a letter to the President, saying that he suspected that the US was likely to be supporting and coordinating PJAK. Later on, in November 2006, journalist Seymour Hersh, writing in The New Yorker, supported this claim, stating that the US military and the Israelis are giving the group equipment, training, and targeting information in order to cause destruction in Iran. The claims were denied officially by both the U.S. and PJAK, but the group’s spokesman also mentioned that PJAK wished to be supported by and work with the United States in a similar way to the U.S. cooperation with Kurdish organizations in Iraq in overthrowing the Saddam Hussein regime. In August 2007, the leader of PJAK visited Washington, to seek more open support from the U.S. both politically and militarily, but it was later said that he only made limited contacts with officials in Washington.

Iraq

In Iraq, the rebellions of the Kurds against the central authority began shortly after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, when Mahmud Barzanji began secession attempts and in 1922 proclaimed the “Kingdom of Kurdistan”. After Mahmud’s insurrections were defeated, another Kurdish sheikh, Ahmed Barzani, began to actively oppose the central rule during the 1920s. The first of the revolts took place in 1931, but eventually Barzani failed and took refuge in Turkey. The next serious Kurdish secession attempt was made by Ahmed Barzani’s younger brother, Mustafa Barzani (Mulla Mustafa), in 1943, but the revolt failed as well, resulting in exile of Mustafa Barzani to Iran, where he participated in the establishment of the Soviet-backed “Republic of Mahabad” and founded the “Kurdistan Democratic Party” (KDP).

In 1958, Mulla Mustafa Barzani and his fighters returned to Iraq and an attempt was made to negotiate a Kurdish autonomy in the north with the new Iraqi regime. The negotiations ultimately failed and the Kurdish-Iraqi War erupted on 11 September 1961, lasting until 1970. The attempts to resolve the conflict by providing Kurds with a recognized autonomy in North Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan) failed in 1974 and the conflict resumed (the second Kurdish-Iraq war), resulting in the defeat of the Kurdish militias and the occupation of northern Iraq by Iraqi government troops. As a result, Mustafa Barzani and most of KDP leadership fled to Iran, while the local power was gained by a group of former KDP dissidents who founded the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), led by Jalal Talabani (the current president of Iraq).

The PUK was a coalition of several separate political entities, the most significant of which were Talabani and his closest followers, the clandestine Marxist-Leninist group Komala, and the Kurdistan Socialist Movement (KSM). The PUK served as an umbrella organization unifying various trends within the Kurdish political movements, finally merging in 1992. The PUK received grass roots support from the urban intellectual classes of Iraqi Kurdistan upon its establishment, partly due to 13 of its 15 founding members being PhD holders and academics.

Since 1976, PUK and KDP relations deteriorated, reaching the climax in April 1978, when PUK troops suffered a major defeat by KDP, which had the support of Iranian and Iraqi air forces. The conflict with Iraq re-emerged as part of the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war, with the Kurdish parties collaborating against Saddam Hussein, and KDP also having military support from Iran. By 1986, the Iraqi leadership began a genocidal campaign, known as Al-Anfal, to oust the Kurdish fighters and take revenge on the Kurdish population – an act often described as the Kurdish genocide, with an estimated 50,000 – 200,000 casualties.

In 1991, in the aftermath of the Gulf War, the Kurds succeeded in achieving a status of unrecognized autonomy within one of the Iraqi no-fly zones, established by the U.S.-led coalition, and the PUK jointly with the KDP administered Iraqi Kurdistan (Kurdistan Region of Iraq).

Since 1994, the parties engaged into a three year conflict, known as the Kurdish Iraqi Civil War. The conflict ended with U.S. mediation, and reconciliation was eventually achieved in 1997. The most valuable gains of the Kurds occurred in 2003 and 2005, after having contributed to the toppling of the Saddam Hussein regime and the Kurdish autonomy gained recognition by the new Iraqi government. The Iraqi constitution of 2005 defines Iraqi Kurdistan as a federal entity of Iraq, and establishes Arabic and Kurdish as Iraq’s joint official languages.

The establishment of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq dates back to the March 1970 autonomy agreement between the Kurdish opposition and the Iraqi government. It was left by the Iraqi troops in October 1991, to function de facto independently; however, neither of the two major Kurdish parties had at any time declared independence and Iraqi Kurdistan continues to view itself as an integral part of a united Iraq but one in which it administers its own affairs. The region is officially governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Despite the mutual recognition, the relations of Iraqi Kurdistan and the Republic of Iraq grew strained in 2011-2012 due to power sharing issues and the export of oil.

On the other hand, KRG developed strong relations with Turkey, based on the economic mutual interest and using the connections made through the only Turkish institution working in Arbil, the pro-Fethullah Gülen Fezalar Eğitim Kurumları (Fezalar Educational Institutes), which had close ties with the Justice and Development Party (AKP) through its ally, the Kurdistan Islamic Union (KIU). Also, because the Gülen movement’s ideological background is based on Kurdish Islamic scholar Said Nursi’s thoughts, the institute was accepted by Kurds, especially those who are religious. Many intellectuals believed that this movement, a mixture between Kurdish and Turkish leadership, was in the best position to bring Turks and Kurds closer.

Syria

The Kurds are the largest ethnic minority in Syria with about 2 million people, inhabiting regions in the northern and northeastern parts of the country (where a large percentage of the country’s oil supplies is located) and making up about nine percent of the country’s population. Many Kurds are seeking political autonomy for the Kurdish inhabited areas of Syria, similar to the Iraqi Kurdistan, or outright independence in a Kurdish nation state.

Anti-government sentiment has been present among the Kurdish population for a long time, since the Syrian government does not officially acknowledge the existence of Kurds in Syria. A number of Kurds were stripped of their citizenship and were registered as foreigners. The Kurdish language and culture has also been suppressed. Since 2004, several riots in Syria’s Kurdish areas have prompted increased tension, and occasional clashes between Kurdish protesters and government forces have occurred since then.

Kurds participated in the early stages of the Syrian uprising in smaller numbers than their Syrian Arab counterparts, partly due to the Turkish endorsement of the opposition and Kurdish under-representation in the Syrian National Council (SNC). The National Movement of Kurdish Parties in Syria, which consisted of Syria’s 12 Kurdish parties, boycotted a Syrian opposition summit in Antalya, Turkey on 31 May 2011, stating that “any such meeting held in Turkey can only be a detriment to the Kurds in Syria, because Turkey is against the aspirations of the Kurds, not just with regards to northern Kurdistan, but in all four parts of Kurdistan, including the Kurdish region of Syria”. Only two of the parties in the National Movement of Kurdish Parties in Syria, the Kurdish Union Party and the Kurdish Freedom Party, attended the August 2011 summit in Istanbul, which led to the creation of the Syrian National Council.

Anti-government protests had been ongoing in the Kurdish inhabited areas of Syria since March 2012, as part of the wider Syrian uprising, but clashes started after the opposition Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Kurdish National Council (KNC) signed a seven-point agreement in June 2012, under the auspice of the Iraqi Kurdistan’s president Massoud Barzani. This agreement failed to be implemented and a new cooperation agreement between the two sides was signed in July 2012 which saw the creation of the Kurdish Supreme Committee as a governing body of all Kurdish-controlled territories.

In the context of the ongoing civil war in Syria, the government forces have abandoned many Kurdish-populated areas, leaving the Kurds to fill the power vacuum and govern these areas autonomously.The newly created Popular Protection Units (YPG) stormed and captured several places in the Kurdish area and the KNC and PYD formed a joint leadership council to run the captured cities. The ease with which Kurdish forces captured the towns and the government troops pulled back was speculated to be due to the government reaching an agreement with the Kurds so military forces from the area could be freed up to engage opposition forces in the rest of the country. On 2 August 2012, it was announced that most Kurdish dominated cities in Syria were no longer occupied by government forces and were being governed by Kurdish political parties.

Kurdish in exile and international support

The Kurdish separatist groups, mainly the PKK, are consistently supported by donations from both organizations and individuals from around the world. Some of these supporters are Kurdish businessmen in south-eastern Turkey, sympathizers in Syria and Iran, and Europe. Other funds come from the sale of various publications, as well as revenues from legitimate businesses owned by the organizations.

Labor migration since the 1960s, family reunion since the 1970s, and a vast stream of asylum-seekers since the 1980s have resulted in huge numbers of Kurds in most West European countries though not to a single well-organized Kurdish Diaspora. The existence of large Kurdish communities has enabled the activist minority to raise funds, recruit devoted supporters, lobby national and European institutions, and to engage in a level of cultural production and reproduction that has a significant impact on Kurdish society in the region of origin.

The most important Kurdish organizations in Europe are the Confederation of Kurdish Associations in Europe (KON-KURD), headquartered in Brussels and the International Kurdish Businessmen Union (KAR-SAZ), based in Rotterdam, which constantly exchange information and perform legitimate or semi-legitimate commercial activities and donations.

The KON-KURD member organizations are mainly located in the European countries, with some associations from Australia and Canada also belonging to the federation. KON-KURD is the biggest organization of Kurds in exile, with most of the members being Kurds from Turkey.

According to a INTERPOL report, in the early 90ies about 178 Kurdish organizations were suspected of illegal drug trade involvement, and members of the PKK have been designated narcotics traffickers by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

The fact that PKK is considered a terrorist organization in Europe, but also the lack of a Kurdish state are seen as the main obstacles in the Kurds’ securing more visibility and media attention. In this context, analysts note the increasing influence in Western Europe of the (Iraq) Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), due to its de facto statehood and its possibility to offer business opportunities, a possibility that Kurds in Turkey don’t have.

In the United States, Kurdish immigration began after World War I, with several waves of migration, including a more significant one in the late 70ies, when Kurds immigrated from Iraq and Iran. The third wave arrived between 1991 and 1992, following the Kurdish support for Iran in the Iran-Iraq War. The most recent wave of migration came between 1996 and 1997, in the context of the civil war between Iraqi Kurdistan’s two major political parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). Most of the immigrants have the status of political refugees from Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. The Kurdish population in the United States was 9,423 according to the 2000 census, with Nashville, Tennessee having the largest number.

The Turkish authorities accused many times that the Kurdish separatist movements were supported by other countries although their activities were considered as terrorist. Such accusations were made against Armenia, Greece, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Russia and Syria.

In the case of Russia, former KGB-FSB officer Alexander Litvinenko, who was poisoned in 2006, is cited for declaring that PKK’s leader Abdullah Öcalan was trained by KGB-FSB[9].

Also, the Turkish authorities are accusing that, despite PKK being considered a terrorist organization by the European Union, European countries allowed the activities of the Kurdish broadcasting networks and permitted Kurdish separatist leaders to move and live in Europe, as well as to develop high-placed relations that favored the Kurdish interests.

In 2007, the Chief of the Turkish General Staff stated that even though the international struggle had been discussed on every platform and even though organizations such as the UN, NATO, and EU made statements of serious commitment, the necessary measures had not been taken.

4. Integrating into state-type organizations

In the recent years, the analysts noted the increasing trend of political integration among various parties and organizations active in all the territories of Kurdistan, as well as efforts to develop a Kurdish armed force out of the traditional Peshmerga troops.

Political integration

On the political side, one of the most significant developments is to be seen in the Union of Communities in Kurdistan (Koma Civakên Kurdistan – KCK), formerly named Peoples’ Confederation of Kurdistan(Koma Komalên Kurdistan – KKK), founded in 2005 by Abdullah Öcalan and based on his ideology of “democratic confederalism”, exposed in the Declaration of Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan issued in March 2005.

According to Öcalan, “the democratic confederalism of Kurdistan is not a State system; it is the democratic system of a people without a State… It takes its power from the people and adopts to reach self sufficiency in every field including economy.

The democratic confederalism is the movement of the Kurdish people to found their own democracy and organize their own social system… The democratic confederalism is the expression of the democratic union of the Kurdish people that have been split into four parts and have spread all over the world… It develops the (notion of) a democratic nation instead of the nationalist-statist nation based on strict borders”. Developing the principle, the KCK executive leader, Murat Karayılan, mentioned[10] that “the alternative is the independent self-declaration of the democratic confederate system. (…) The society should be independent, the nation should be independent. Yet, the main purpose should be for independent nations to form a democratic nation community together and based on equality, within a confederate system… It is a system of partnering, where various cultures live together”.

Abdullah Öcalan is KCK’s honorary leader, and the organization is led by an Assembly called Kurdistan People’s Congress (Kongra Gelê Kurdistan – Kongra-Gel), which serves as the group’s legislature. There are five main subdivisions of the KCK: the ideological front, the social front, the political front, the military front and the women’s division. Kongra-Gel is headed up by Zübeyir Aydar, and Murat Karayılan leads the so-called “executive council”. Karayılan’s assistants are Duran Kalkan, Mustafa Karasu and Cemil Bayık. The units known as the “people’s defense powers” are autonomous organizations within the KCK. As for the PKK, in the KCK’s “constitution” it is defined as the “ideological power behind the KCK system”, responsible for bringing into practice its philosophy of leadership and its ideology. The KCK is run by the executive group led by Karayılan from the Kandil Mountains in northern Iraq. This organ coordinates all of the various institutions, units and organizations of the KCK in Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq.

In addition to the PKK, political parties such as the Iranian PJAK and the Syirian PYD, as well as civil society organizations, are included in KCK. In Iraq the party is called Kurdistan Democratic Solution Party(Partiya Çaresera Demokratik Kurdistan – PÇDK).

KCK is banned in Turkey, where many members were detained, especially after the interdiction enforced for the Democratic Society Party (DTP) in 2009. Most suspects have been charged with membership of an illegal organization under Article 314 of the Turkish Penal Code. One of the final verdicts (most of them issued in 2012) mentioned that the KCK is acting with the aim of turning the PKK into a separate state structure.

According to the Turkish analysts, the KCK is to be regarded not as the political branch of the PKK, but a “shadow state”. The KCK possesses both a lateral and a pyramid organizational structure, and is active not only in Turkey but also in Syria, Iran and Iraq. By forming an alternative to the official organs of justice, management and politics in these countries, it provides a roof under which its supporters can gather.

The KCK bestows and revokes citizenship, imposes tax obligations and tries people in courts, engages in armed battle, has both local and central units, makes an effort to control regional leadership. The KCK – which has spread out to cities, towns, neighborhoods, streets, village organizations, communes and homes – uses a flag with a red star on a yellow sun with 21 rays on a green base. Its justice system includes an executive high court, a people’s free court, and a high electoral board. Crimes that occur in its military arena are addressed by its High Military Court.

According to the KCK contract, those attached to the KCK system are defined as “citizens” or “countrymen”. People who betray the principles or aims of the KCK can have their citizenship revoked by decision of the “people’s courts”. Every person living in areas under the rule of the KCK is obligated to actively participate in defense actions when there is a state of war. Every KCK citizen is also obliged to pay taxes.

Peshmerga: the Kurdish armed forces

The Kurdish armed fighters in northern Iraq are known as the Peshmerga or Peshmerge(“those who face death”), and have been in existence since the advent of the Kurdish independence movement in the early 1920s, following the collapse of the Ottoman and Qajar empires that had jointly ruled over the area. Peshmerga forces include women in their ranks, and Kurds say that all Kurds willing to fight for their rights are Peshmerga.

The roots of the modern-day Peshmerga can be found in the early attempts of the Ottoman Empire to create an organized Turkish-Kurdish military force, to defend the Cossack Region from a possible Russian threat, and to reduce the potential of Kurdish-Armenian cooperation. This force, called the Hamidiya Cavalry may also have been instituted to create a feeling of “Pan-Islam”, especially in light of a perceived possible British-Russian-Armenian Christian alliance.

Through much of the 1990s, the Peshmerga came into conflict with the Iraqi forces, using guerilla warfare tactics against them. Many of the Peshmerga were led by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP – led by the Barzanis), while others were under the command of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK – led by Jalal Talabani and later by Kosrat Rasul Ali). Following the First Gulf War, Iraqi Kurdistan fell into a state of civil war between the two major Kurdish parties the KDP and the PUK, and their Peshmerga forces were used to fight each other. The civil war among the Peshmergas of the PUK and the KDP held up the military development of the Peshmerga as the attention was no longer on outside threats.

After the 1998 “Washington Agreement” secured by the U.S. between the KDP and the PUK, the fight between their Peshmerga units came to an end. As active PUK Peshmerga put down their weapons, elder veterans began filling more political PUK roles. The U.S. insisted on the Peshmerga stand down if the Kurdish parties wished to be included among continuing U.S.-sponsored Iraqi opposition groups, so the Kurdish groups had to accept the U.S. policy to overthrow Saddam Hussein’s regime.

During operation Iraqi Freedom (2003), the deployment of CIA agents to Kurdistanfollowed by the U.S. Special Forceswas the beginning ofa close cooperation with Peshmerga forces. Arriving in July 2002, on a supposed counterterrorism mission, the CIA seldom worked with the Peshmerga, since the true mission was to acquire intelligence about the Iraqi government and military. The CIA-Peshmerga operations eventually went beyond the scope of intelligence gathering however, as PUK Peshmerga were used to destroy key rail lines and buildings prior to the U.S. attack in March 2003. Peshmerga cooperation with the 10thU.S Special Forces Group was even closer, since in January 2003, the Peshmerga became an integral part of the US military operations. As confidence in American intentions increased, PUK and KDP Peshmerga were again placed under the command of foreign leadership.

With the occupation of Baghdad by U.S. forces on 9 April 2003, the Iraqi army was all but completely defeated. The combined Peshmerga-U.S. assault from 21 March to 12 April 2003 defeated 13 Iraqi divisions, prevented Iraqi forces from reinforcing their southern defenses, captured strategic airfields throughout northern Iraq, and diminished the ability of the Ansar al-Islam terrorist group. The Kurdish Peshmerga, assisted by the U.S. military, were finally able to defeat the Iraqi military and open a new chapter in Kurdish history.

After the war, the Peshmerga have assumed full responsibility for the security of the Kurdish areas of Northern Iraq. Trained by U.S. and Israeli officers, they began to take the place of party-controlled Peshmerga on the Iranian border, or were assigned to protect vital oil pipelines, while others continued operations with the U.S. Special Forces. Nearly 7,000 Peshmerga, nicknamed “Peshrambo”, were trained in commando operations and assisted in the hunt for Ansar al-Islam and other Al-Qaeda related militants. Since 2003, training between the Peshmerga and the U.S. has evolved into a mutual relationship. As U.S. forces were deployed to Iraq, Kurdish-Americans have started helping American troops prepare for their mission while on American soil.

Although the Peshmerga’s military integration has been cautious, political relations with the Kurdish leadership took a large step forward when former Peshmerga leader and PUK founder Jalal Talabani was elected President of Iraq in May 2005.With Masoud Barzani (KDP) elected President of Iraqi Kurdistan in June 2005,the potential to achieve the goals of generations of Peshmerga became greatly enhanced. However, the broken promises of the past have forced the Kurds to look to their own as the most reliable means of protection, since the Kurds have been “abandoned” by three of the world’s premier superpowers: the British in the 1920s, the Soviet Union in the 1940s, and the U.S. in both the 1970s and the 1990s. Politically, members of the Kurdish parties have called the armed resistance the “only alternative for revitalizing the Kurdish liberation movement”. Socially, the Peshmerga have become heroes.

Analysts agree that the ideal of the Peshmerga as “guardians” of Kurdish nationalism will continue far beyond the generation of Massoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani. As older Peshmerga step away from the battlefield and assume political roles, new Peshmerga fill the ranks. Even Iraqi Kurdish children are considered future Peshmerga and their involvement in the cause is looked at approvingly by their parents.

5. The “Kurdish Spring”: reshaping regional relations

Most analysts agree that the rise of the Kurdish nationalism – the so-called “Kurdish Spring” – is a factor that might influence the evolution of all the four countries with Kurdish population, as well as the regional relations.

The Kurdish “oil and gas trump”

Analysts consider that the “Kurdish Spring” impetus largely benefits from the oil boom in the Kurdish Region of northern Iraq, where KRG announced its plans to raise its output to one million barrels per day by 2015 withmore discoveries expected that would result in a possible 2 million barrels per day by 2019.This would qualify Iraqi Kurds for membership in OPEC if they had their own sovereign state. In addition, the region could produce as much as 15 million cubic meters of gas annually.

Even without a state, the Iraqi Kurdish region begins to attract international business, and recently Exxon Mobil, the US oil giant, has signed up to explore for oil and gas, despite warnings from the government in Baghdad that it will be frozen out of contracts in the rest of Iraq if it goes into business with the Kurds. Also, the French Total, Norway’s Statoil, U.S. Chevron and even Russia’s Gazprom Neft are looking at exploration blocks in Iraqi Kurdistan.

In June 2012, the Baghdad government asked U.S. President Barack Obama to stop Exxon Mobil exploring for oil in Kurdistan, saying that the company’s actions could have dire consequences for the country’s stability, adding to the already rising territorial tensions between Kurdistan and Baghdad after the U.S. troops withdrew from Iraq. Iraqi Kurdistan has also clashed with the central government over oil rights, and halted its crude exports, after accusing Baghdad of not making due payments.

In another important development, Kurdistan has started plans to begin exporting its crude oil along a new pipeline to the Turkish border by August 2013, after Turkey announced that it was prepared to import oil directly from Kurdistan despite Baghdad’s stance that it has the sole right to exports. Even before that, industry sources say the KRG is preparing to move crude by tanker truck to Turkey, possibly as part of a crude-for-products swap with Turkey.

There are plans for two new pipelines that would pump crude from Kirkuk[11], in Northern Iraq, to Ceyhan, the first is scheduled to come on line in August 2013; the second, in early 2014. This would all tie into the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline and its capacity of 1 million bpd of Caspian oil. Expanding the BTC to include sizable Iraqi Kurd output would turn Ceyhan into a major hub. Furthermore, the Turks have contracted out an infrastructure project to transport Kurdish natural gas to Turkey.

Iraqi Kurdistan also has resources estimated up to between 100 trillion to 200 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and the future Nabucco pipeline project needs 1.1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas per year, meaning the KRG can supply the entire needs of Nabucco. Together with Azeri oil and gas, the Kurdish resources could be an alternative to Russia and Iran for the needs of Europe.

The energetic advantage is already being used by KRG that does not want to become part of a new Iraqi hydrocarbons law, which continues to languish in Baghdad’s parliament. According to intelligence analysts in the field, since the KRG’s own oil and gas regulations are good enough for the foreign companies operating in the region, KRG is interested to use its new position for its end objective, which is clearly independence, and there are plenty of external forces who would like to see greater autonomy, and even independence, for Iraqi Kurdistan. In their vision, Iraq has already been carved up, with Northern Iraq controlled by Turkey, the US, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, and the rest controlled by Iran.

Turkey: bound to change

The energy boom in Iraqi Kurdistan and, on the other hand, the Syrian civil war that allowed Syria’s Kurdish minority to take control of parts of the north-east, bordering Turkey and Iraq, with Kurdish flags flying over border towns (seeming to signal the end of Syria as a unitary state) are seen to have a significant effect in Turkey, affecting even the Justice and Development Party (AKP)’s “zero problems with neighbors” foreign policy.

Ankara is equally alarmed about prospects of Kurdish nationalism and a greater Kurdistan emerging in the region. With the presence of the Kurdish regional government in Iraq, a newly formed Kurdish region in Syria, and Iran’s own Kurdish region, soon Turkey might see Kurdish entities at all its three southern borders.

Externally, as Shia-Sunni and Arab-Kurdish schisms widened in Iraq and Syria, and Iran’s regional influence grew, Turkish neutrality vis-à-vis different ethnic and religious groups became more difficult to maintain. Turkey had long feared that Kurdish nationalism in its neighborhood would stir ethnic trouble at home, but now religious tensions may also be in play. Domestic politics have been increasingly preoccupied with cleavages between Turkish Sunnis and Alevis, and many interpret Turkey’s Syrian policy as a U.S.-Israeli plot to strike Shia Iran by using “Sunni Turkey”. Consequently, Turkey’s relations with Iran have been deteriorating rapidly, with Iran recently warning Turkey that it would be facing reprisals if it continued to support western (i.e., anti-Iran) policies in Syria.

Turkey also finds itself obliged to reconsider its relations with the Kurds since the groups that control the north-eastern parts of Syria are associated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The sight of PKK flags and posters of PKK leader Abdullah Őcalan, so close to Turkish soil, shocked mainstream public opinion in Turkey, and PKK attacks inside Turkey increased. Reportedly, recently the Turkish army needed last-minute intelligence and a pre-emptive battle to foil a PKK plan to start an insurgency in Semdinli, a Turkish town in the sensitive wedge where Iraq, Iran and Turkey meet.

Consequently, the AKP government is already showing a different approach of its problem with PKK. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan used a recent visit to the Kurdish region to call for unity between Turks and Kurds, amid speculation that a new initiative to solve the long-running Kurdish conflict might be started.

Mr. Erdogan also said he was ready to re-launch talks with the jailed PKK leader Abdullah Őcalan and that, to that effect, the Turkish intelligence service could “do anything at any moment”, if asked by the government. The government conducted confidential talks with both Őcalan, who remains a revered figure among many Kurds, and PKK representatives through Turkey’s National Intelligence Service (MIT), but negotiations ended without a result last year. According to Kurdish sources, new closed-door negotiations may already have begun.

On the other hand, the current Turkish process for writing a new constitution – through a multi-party parliamentary commission including most political forces – provides an opportunity to reconfigure the status of Kurds and other groups.

If Ankara manages to find solutions for the Kurdish problem, analysts see Turkey as having a good opportunity to play a major role in shaping the borders of the emerging Middle East map, even to include a Kurdish state entity, in the context of Syria’s likely fragmentation.

Since between 10-20 percent of the Syrian population is Kurdish and the largest concentrations of Kurds in Syria live along the Turkish border areas and stretching eastward towards Iraq, Syria’s Kurds would appreciate Ankara as a balancing force against Arab nationalism, a lesson they would fast learn from the Iraqi Kurds, who have made Turkey their protector against Baghdad since 2010.

Turkish, Syrian, and Iraqi Kurds (at least the ones that live in Iraq’s northwest, across the borders with Turkey and Syria) are linguistically united. These Kurds speak the Kurmanchi variety of Kurdish, as opposed to Iranians and northeastern Iraqi Kurds, who speak the Sorani variety of Kurdish, which is more different from Kurmanchi than Portuguese is from Spanish.

This – together with the prospect of chronically unstable Sunni Arab neighbors, and the need to counter Iran’s Shia axis, currently stretching from Baghdad to the Assad regime to Hezbollah in Lebanon – might change Turkey’s traditional hostility to an independent Kurdish state or entity anywhere in the region, lest its own Kurdish population make similar demands. Also, the recent shelling across the Turkish-Syrian border presented an important case for why Turkey might be better served by buffer states such as Kurdistan, rather than the far-less defined geographic realities today. Also, Turkey ought to favor a new Aleppo-based government that would act more responsibly, as Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has, in reigning in PKK militias.

Furthermore, as in Iraqi Kurdistan, where more than 1,000 Turkish companies are currently operating, Turkish infrastructure companies would be among the prime beneficiaries of investment in Syria’s Kurdish region post-Assad, winning major contracts, as they did in Iraqi Kurdistan after Saddam. Similarly, it is a necessary trade partner for any landlocked entity emerging in the post-Assad aftermath. Turkey’s competitive advantage in Iraq, as an advanced economy that lies next door, will be its advantage also in post-Assad Syria.

Syrian Kurds: a place for Russia

For Syria’s Kurdish community the crisis in Syria provided unexpected opportunities to initiate diplomatic discussions with Russia, China and Iran in its pursuit of regional autonomy, speculating on the fact that Russia, Iran and China are opposed to outside intervention by the Western states or Turkey and prefer to find alternatives.

The PKK and its Syrian affiliate PYD tried to counter Turkish influence by joining the National Coordinating Body for Democratic Change in Syria (NCB) that supports the Kofi Annan plan and a peaceful transition and dialogue with the regime and is against any foreign intervention. As such, it is a useful opposition alternative to the SNC for Russia. The fact that PYD and NCB are talking with a foreign ally of Assad does not change the fact that toppling the Assad-government will be difficult without foreign intervention. Some opposition members recognize that a dialogue with Russia is necessary, given the fact that Russia, as a UN Security Council member, can support or veto UN motions and is also in a position to pressure Assad to make changes. The same goes for Iran and China.

Although the PYD claims its talks with the Russian government are designed to support the Annan peace plan, in reality it wants to prevent an international intervention led by Turkey or the creation of a Turkish-supported humanitarian corridor that could lead to Turkish dominance over Kurdish areas in Syria. Furthermore, if the NCB does succeed in creating a transitional government, the PYD would be assured of future influence in the Syrian government through the role it played with Russia and could then play a stabilizing role in a post-Assad Syria.

Iran: worrying about “Kurdish Spring” repercussions

Iran is troubled by the upheavals in Syria – not only because it stands to lose its most important ally, but also because of the possible repercussions for Iran in general, and the Kurds in particular, should Assad’s regime collapse. If the upheavals reach Iran, the Kurds in that country will be pressing for change because of the double repression under the Islamic republic, the synergy of cooperation with the other parts of Kurdistan, and the nationalist fervor among organizations in the Diaspora.

The Kurds of Iran outnumber those in Iraq and far outnumber those of Syria. They also have great potential on the intellectual-scientific front, as attested by the large number of Kurdish intellectuals in the Diaspora. On the whole, a large number of the latter are active in the Kurdish national movement, providing it with indispensable organizational links with the outside world.

Iran is worried by the support given to the Iranian Kurdish parties by the Iraqi Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), that provided safe haven for various Kurdish Iranian groupings such as Komala and the KDPI, two groups that, after fighting each other for a long time, recently signed an agreement calling for the toppling of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the establishment of a federal system in Iran and the separation of religion from the state. The Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK), seen as the Iranian Kurdish offshoot of PKK, is also based in Iraqi Kurdistan, and Tehran is strongly suspecting PJAK of benefitting from American assistance, thanks to its activities against the Islamic Republic.

6. The Kurdish state: a new Israel?

The events in the Middle East and the so-called “Kurdish Spring” made many analysts draw a parallel between the growing chances of including a Kurdish state in a new map of the Middle East and the creation of the Israel after World War Two.

The Kurdish revival in Iraq in the 1990s resembles in some ways that of the Jews in the 1940s. Four years after a genocidal war waged against them by the Ba‘athi regime of Saddam Hussein in 1988–89, the Kurds managed to launch an ambitious project of nation- and state-building.

The KRG managed to establish a Kurdish national entity functionally separated, at least in part, from the Iraqi state. The autonomous prerogatives of the KRG cover a wide range of areas. It holds elections to the Kurdish parliament independently of the central/federal government. It has a draft constitution, endorsed by the Kurdish parliament in June 2009, as well as an elected President. In addition the Kurds have national symbols of identity such as an anthem, a national day (Nowruz) and a flag. Another important marker of statehood is the border between the KRG and the Arab part of Iraq. The many checkpoints in operation are meant to imply de facto independence. Another important emblem of the new Kurdish sovereignty is the turning of the Peshmerga (see the previous chapter), into a conventional army, with paid soldiers, a modern organizational structure, rank insignias and uniforms.

On another level of sovereignty, the KRG has developed foreign relations independently from Baghdad. The acceptance of a higher KRG political status, especially by the United States, has been crucial for enhancing the Kurdish political and strategic profile. The KRG leadership also sent commercial representatives and all-but-official ambassadors to various world capitals. Meanwhile, some 25 states have opened consulates in Erbil, the KRG capital.

External factors

Just as a conjugation of various domestic, regional and international factors made possible the rise and defense of the State of Israel only three or four years after World War Two, the Kurdish success in Iraq and the chances for the creation of a Kurdish “historic” state (similar to Israel) are favored by a conjugation of factors.

As with the Jews, the main factor is seen to be the internal cohesion of the Kurdish people into a nation, despite territorial, political and even cultural division. However, factors beyond Kurdish influence are to be taken into account. Among them analysts mention the collapse of the Iraqi state model and the shift of emphasis from the 20th-century struggle between Arab and Kurdish nationalisms to the Sunni-Shia struggle at the beginning of the 21st century. The consolidation of KRG (considered by many analysts as the core of a future Kurdish state) also changed the political and psychological geometry of the region, leading the Turkish, Syrian and Iranian regimes to see the KRG and its relationship with Baghdad in a new light.

If in the 1990s, and even in the early 2000s, the surrounding states collaborated to prevent Kurdistan from drifting toward independence, this collaboration has now ended. Turkey and Iran now seem to be on a collision course; the short-lived Turkish-Syrian collaboration ended as everyone, not least the regime in Tehran, awaits the outcome of the Syrian civil war. Baghdad did not recovered from war and the Iraqi government acquiesced to the formula of federalism. Tehran has been weakened because of the international response to its nuclear program. Furthermore, Tehran and Ankara seem to have reached a tacit understanding with regard to the division of spheres of influence in the Arab and Kurdish parts of Iraq respectively; the Iranians concentrated on Baghdad, the Turks on Erbil.

On the other hand, the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq reinforced the strategic importance of KRG. The rivalry that developed between Iran and Turkey increased the KRG’s significance in both American and Turkish eyes. Similarly, deteriorating relations between Sunni Ankara and Shia Baghdad accelerated as a result of the American withdrawal and turned the Sunni KRG into an ally for Turkey in the region’s sectarian calculus. Meanwhile, a new virtual tripartite alignment formed that came to include Washington, Ankara and Erbil. Having proved its loyalty to the United States and the West in general, the KRG became the least unreliable partner in sight for both the United States and Turkey.

Risks and drawbacks

The process of creation of a Kurdish state is, however, mined by internal and external risks, that might delay or even make impossible in the near future.

A very important drawback consists in the differences that exist between the Kurdish communities. The Kurds are a clan-based society, and the different dialects of Kurdish are not all mutually comprehensible. The idea of all the Kurds coalescing into a state is seen by some analysts as less realistic, given the variety of political parties and armed groups.

As for the Kurdish-inhabited areas of Syria, the population is mixed Kurdish-Arab, any form of Syrian Kurdish autonomy or self-rule will have to address the internal challenges and fragmentations among the Syrian Kurdish community. Despite the signed “unity agreements”, there is no real agreement between the Syrian Kurdish groups on leadership, organization and objectives.

At the regional level, the Kurds must be reliant on regional cooperation to sustain any level of prosperity or security in the current geopolitical landscape. Kurdistan in general, especially Iraqi Kurdistan, is landlocked and lacks any independent way to export resources. Even with control of oil-rich Kirkuk, the Kurds must rely on pipelines traversing Turkish or Arab Iraqi lands. As long as the current landscape created by the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 and the treaties of World War I stands, the Kurds are at the mercy of their neighbors.

The success of the KRG autonomous area stems from the limited freedom of action it has, squeezed between the hammer of Turkey and the anvil of Baghdad. Such a precarious existence has demanded mature leadership, which might be in short supply if the autonomous region expanded into new territories.

7. Conclusion: New Map for an unchartered territory

Most analysts do not dare to predict a term for the creation of a Kurdish state or for the re-drawing of the Middle East map. However, they agree that the Kurds’ quest for a state of their own will play a significant role in the process of developing a new system in the lands between the Mediterranean and Iran.

If achieved, a new Kurdish “historic state”, non-Arabic, similar to the Israeli model of the late 40ies, would constitute the core for a whole new regional system in the Middle East and would trigger the process of re-defining the geopolitical order in the area. That would be even more necessary if a Kurdish state will be followed, sooner or later, by, for example, a Baluchi state further East that will mean new problems for Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan and the whole Central Asia.

For the moment, given the landlocked nature of the Kurdistan Region and the geographically contiguous nature of Kurdish populations in Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Syria, analysts consider that Kurdish borders cannot be re-drawn simply because central governments are currently weak and there are opportunities for Kurds to claim control of these territories. What is more likely are greater border security problems and a reaction by regional states, non-state actors, and central governments seeking to reassert their control over the state borders. But until these border changes, or hoped-for changes, are recognized by the international community or at least by regional states, they will remain part of map images and not political reality.

On the other hand, as King Abdullah II of Jordan said recently, “the breakup of Syria … would create problems that would take us decades to come back from”. The conditions that could make those problems unavoidable may already be in place. Just as new and unknown faces have risen to power in a number of Middle East countries over the past year, the very configuration of familiar states and boundaries could change very rapidly as well.

This would jeopardize, in the opinion of many analysts, the entire structure of relationships on which the U.S. strategic agenda in the region rests, and the next Obama presidency will be forced to navigate “undiscovered territory” in charting its policy toward the Middle East. However, in time, if fracking and alternative energy sources ultimately do disperse the concentration of strategic energy wealth around the world, the value of the Middle East to U.S. economic security will diminish and with it the rationale for involvement in the region, including for attacking countries only because they might influence global oil prices.

Another significant trend is given by the fact that, if in the Middle East stability has been imposed for centuries by outsiders (Europeans, Ottomans, Russians and Americans), nowadays the foreigners are less willing and able to accept the costs and risks that come with this role. Americans are worried about jobs and debt – and U.S. foreign policy has shifted focus toward Asia. Europeans are preoccupied with their continent’s crisis of confidence. Russia lacks Soviet-scale international muscle, and the Chinese are worried about China — its slowing economy and the dangers of domestic reform.

The events in the Middle East and the perspective of the West having to confront a new radical wave, as it happened with the “Arab Spring” states, made foreign governments even less willing to involve themselves in the area. This might pave the way for a second phase of the “Arab Spring” process, already called “the Arab Winter”, which might end in an even greater fragmentation of the Arab nations and the creation of the Vatican-type small religious state of Mecca and Medina, as predicted by Ralph Peters, in fact the laicization of Islam.

The result of the global powers’ (mainly the U.S.) withdrawing from the Middle East is an increasing involvement of the regional powers in shaping the future system. Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia – three countries with different political systems, social structures, worldviews and visions for the region – will compete for influence.

Turkey offers the example of a Muslim western-type democracy that can build a modern economy with a relatively open society. Iran is the world’s only theocracy, an international nuclear outlaw and a state sponsor of Shia militancy. Saudi Arabia remains far more socially conservative than either of its influential neighbors and spends freely to promote its Wahhabi conception of Islam. The frictions produced by various forms of conflict among these three will shape the region for many years to come.

The Turkey-Iran relationship are seen to be marked by Iran’s fear that Turkey is undermining Assad’s government in Syria (Iran’s regional ally) and Ankara’s suspicion that Tehran is supporting Kurdish militancy inside Turkey. Turkey and Saudi Arabia have interests in limiting Iran’s regional influence, but they markedly different interpretations of modernity and Islam. The Saudi-Iranian rivalry is central to the region’s potential for conflict – in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and within Saudi and Iranian society.

Other states will play a significant role. Egypt’s government will continue to try to strike a delicate balance between appeasing street-level anger toward America and protecting a relationship with Washington that brings in about $1.3 billion a year in military aid. Qatar’s government will continue to spend money to extend its influence, particularly in Syria. Finally, though Israel is unlikely to launch strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities, the tensions generated by escalating rhetoric on both sides will keep governments and markets on edge.

Over the longer term, regional stability may well benefit as local governments, aware of the fact that there are fewer constraints on their belligerence, will be forced to accept greater responsibility for provocative actions.

[1] The Sykes–Picot Agreement, officially known as the Asia Minor Agreement, was a secret arrangement between the United Kingdom and France defining the proposed spheres of influence in Middle East should the Triple Entente succeed in defeating the Ottoman Empire during World War I. The negotiation occurred between November 1915 and March 1916, between the French diplomat François Georges-Picot and the British Sir Mark Sykes. The agreement was concluded on 16 May 1916. [2]Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Peters (b.1952) worked until 1998 in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, within the U.S. Defense Department, and is known for his fiction and non-fiction writings, including essays on strategy for military journals and U.S. foreign policy. [3] Geoffrey Kemp and Robert Harkavy: Strategic Geography and the Changing Middle East, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1997 [4] Douglas J. Feith: War and Decision: Inside the Pentagon at the Dawn of the War on Terrorism, HarperCollins, New York, 2008 [5] Wesley K. Clark: Winning Modern Wars – Iraq, Terrorism, and the American Empire, PublicAffairs, New York, 2003 [6] The activities of PNAC were treated in a previous paper [7]Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geo-strategic Imperatives (New York City: Basic Books, 1997) [8] The DTP evolved from several Kurdish political groups that formed during the 90ies and were banned, one after another, by the Turkish authorities for allegedly promoting separatism and links with the PKK.

[9]Cf. Chechenpress Dept. of Interviews, 19.07.2005, see http://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/regions/london/2005/07/318875.html [10] in his book “Bir Savaşın Anatomisi”(Anatomy of a War) [11] However, Kirkuk’s official status remains unresolved and it is not officially under the KRG’s jurisdiction, pending a referendum on this issue.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News