Born out of the Iraqi War in 2003, Daesh has stretched across the Middle East and into northern-Africa where today only the Mediterranean Sea separates the militants from Europe. It has conquered regions of Iraq, Syria and Libya while building a strong support structure in Turkey, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Egypt’s Sinai Province, Afghanistan, Tunisia and Algeria.

This expansion is part of its ‘global strategy’ to seize control of destabilized countries while engaging in all-out battle against the West. According to experts from The Institute for the Study of War (ISW), Daesh also has begun to accelerate its operation to activate its ‘sleeper groups” and this is having international effects.

ISW also recorded that in 2015 Daesh pursued simultaneous campaigns to defend territory in Iraq and Syria, to foster affiliates in the region, and to polarize populations globally.

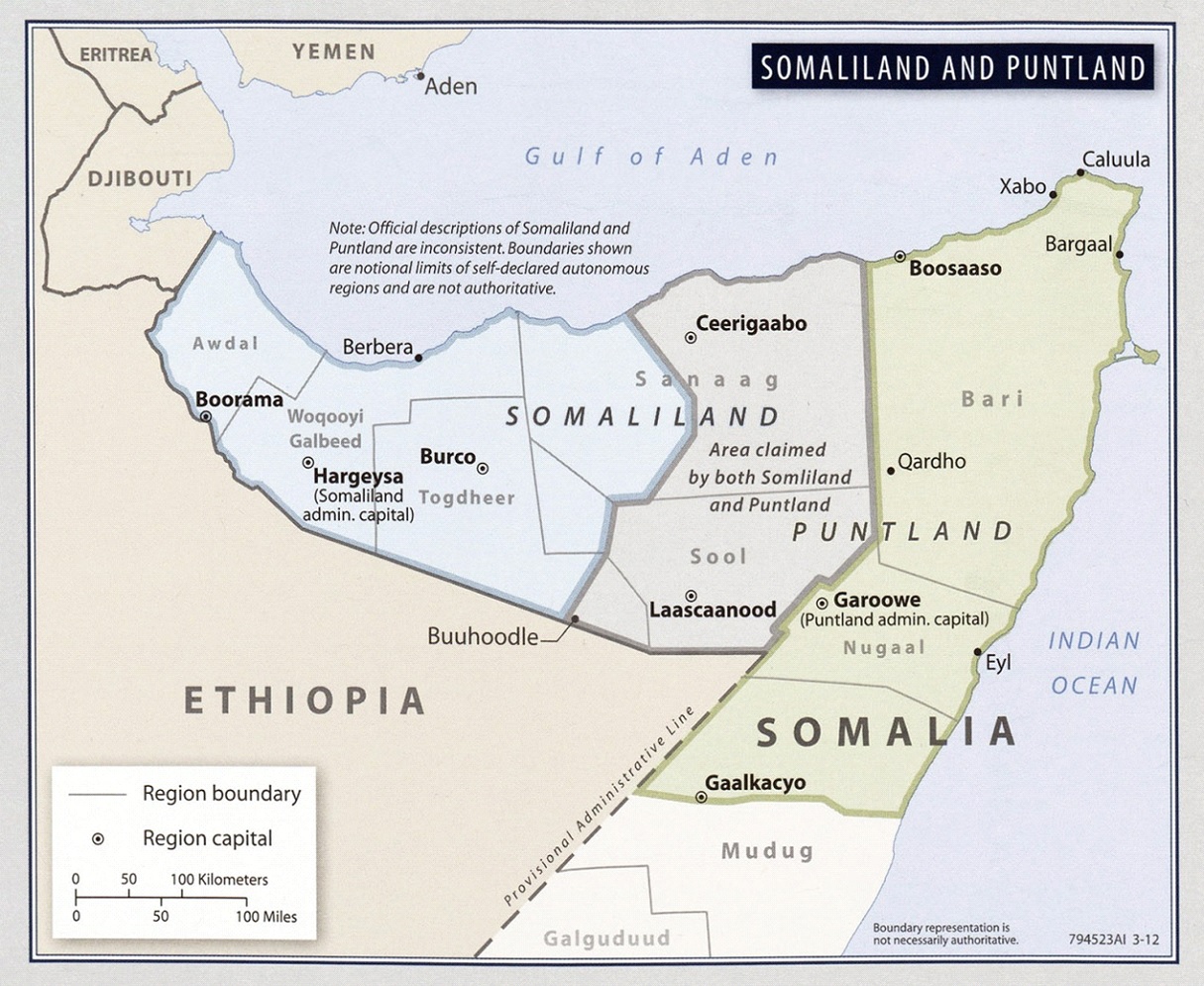

Daesh’s “rings” and wilayat from the Atlantic to the Red Sea and beyond (source: ISW)

Daesh’s parallel campaigns developed three geographic rings. The “Interior” ring includes Jordan, Israel and Palestine, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria, where Daesh focused its main effort to defend the core lands of its so-called “caliphate.” The “Near Abroad” ring is comprised of lands historically held by Arab rulers, stretching from Morocco in the West to Pakistan in the Far East, where Daesh is attempting to expand its influence to offset losses in its Interior. The “Far Abroad” ring encompasses the wider world, including Europe, the United States, Southeast Asia, and cyberspace, where Daesh is attempting to foment a broader war. One of the main goals of Daesh is to expand in the Near and Far Abroad rings to offset the risks of losing terrain in the Interior ring, particularly in Iraq.

Daesh leadership is linked to its regional governorates, or wilayats, in Algeria, Libya, the Sinai, Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Khorasan (Afghanistan-Pakistan). Daesh claims to communicate with local leaders and approve operational concepts in each area. It also reported to provide strategic resources and military training to its most robust wilayats. The groups that constitute wilayats are directly affiliated to Daesh. There are other associated groups and actors worldwide that also appear to align with Daesh. These actors include cells in the Near Abroad and the Far Abroad that contain foreign fighters returning from Iraq and Syria, longstanding members of the overlapping global Daesh and al-Qaeda support networks, and “lone wolves” who conduct individual attacks on behalf of Daesh.

During 2014 and 2015, 42 international groups are believed to have offered support or pledged affiliation to Daesh and its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, according to the Global Terrorism Index published in late 2015 by the Institute for Economics and Peace, suggesting the group is enjoying a rapid growth of influence. Many of these new groups are based in North and West Africa. In fact, terrorism analysts point out to a shifting trend of Daesh’s projected power is from the Persian Gulf region to areas in Africa.

Weak state structures, porous borders, armed conflict and poverty combine to produce a breeding ground for organizations like Daesh. Such conditions, which particularly flourish in the power vacuums that follow the collapse of dictatorships, made it easy for terrorist groups to capitalize on the desperation and resentment in parts of Africa.

Recent developments

The shift of Daesh’s strategy towards North-Western Africa is visible in several recent actions and strikes, particularly in Libya and the Maghreb.

a) At the beginning of January 2016, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) released a video in which it threatens to attack Naples, Rome and Madrid.

The analysis of the video, made by AICS, Spain’s major private intelligence and security company, shows that al-Qaeda is trying to copy Daesh – which has been expanding its influence, in particular in Northern Africa – to recover the power it is losing to the militant group.

The video was released on January 6 and says the terrorists would strike in Naples, Rome and Madrid. AICS found the video in one of the channels through which Islamists spread their propaganda.

AICS CEO Salvador Burguet also stressed that, while the relations between the two groups are “not the best in the world,” in Northern Africa the situation is a bit different, and the two may even merge their forces to launch a major offensive.

According to AICS, at the end of 2015, during several meetings, Daesh representatives in Northern Africa, its affiliate in Algeria, and representatives of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb discussed the possibilities to merge their forces, in order to launch an offensive from South to the North. AICS considers that Daesh needs to expand its activities from Libya to the West, and to do so it needs to cooperate with al-Qaeda, that is why they are “trying to merge both groups and create a common front.”

b) Also at the beginning of the year, on 05.01.2016, the scope of Daesh’s attacks on Libya’s eastern oil ports expanded with at least five oil tanks set on fire amid fears the group could inflict long-term damage on the North African nation’s energy industry.

Four storage tanks were ablaze at eastern Libya’s Es Sider terminal, where Daesh attacks began on January 4. At the neighboring oil port Ras Lanuf, another tank caught fire after the extremist group attacked. A spokesman for the National Oil Co. put the number of burning tanks at seven: five in Es Sider and two in Ras Lanuf.

Libya’s state-owned oil company issued a “cry for help”, after the Daesh attacks. “We are helpless and not being able to do anything against this deliberate destruction to the oil installations,” Libya’s National Oil Corporation said in a statement. “National Oil Corporation urges all faithful and honorable people of this homeland to hurry to rescue what is left from our resources before it is too late.”

Daesh’s chief goal is Libya’s Marsa al Brega oil refinery, also on the Gulf of Sidra, about 50 miles east of Ras Lanuf and the largest such facility in North Africa. This would give the militants control of most of the country’s oil wealth.

According to many observers, Daesh’s strategic goal seems to be not to take over Libya as a functional state, but rather to destabilize it so much that neighboring states have to intervene more heavily than they have already. The terror group will thus use increased fighting with the neighboring Arab states as a means for attracting recruits to its cause, while trying to destabilize those countries, especially Egypt. The ultimate goal of Daesh may be to provoke destabilization in Egypt, Tunisia and Algeria, and eventually hook up via the Sahel with Boko Haram and other jihadist groups, creating a wide arc of instability spanning the Atlantic, Mediterranean and Red Seas.

Daesh’s Expansion in the Maghreb

Western intelligence officials consider that, as Daesh is under growing military and economic pressure in Syria and Iraq, its leaders have looked outward. One manifestation of the shift is a turn toward large-scale terrorist attacks against distant targets, including the massacre in Paris and the bombing of a Russian charter jet over Egypt. The group’s leaders are also devoting new resources and attention to far-flung affiliate groups that pledged their loyalty from places like Egypt, Afghanistan, Nigeria and elsewhere.

Daesh is extending to Africa also looking for recruitment sources. It publishes a ‘recruitment magazine’ aimed at Africa. Under the title ‘Sharia Will Rule Africa’, the magazine refers to West Africa, Algeria, Tunisia, Nigeria, the Sinai and Libya.

The recruiting propaganda employed by Daesh is designed to stress the idea of a re-emergent caliphate, not only in the Middle East, but across the North African littoral, as well as in Sub-Saharan Africa. A map produced by Daesh applies names to parts of Africa that existed during an earlier period of Islamic cultural and religious hegemony, which the group aims to recreate by 2020.

The number of groups in Africa pledging allegiance to Daesh shows the success of such propaganda. Groups on the continent which have pledged allegiance to Daesh such as Boko Haram in Nigeria, have adopted names to conform with the Daesh vision of Africa, such as ‘The Islamic State’s West African Province’ (Nigeria) or ‘The Province of Sinai’ in Egypt. Most significant for the recent trend is Daesh’s ‘offensive’ in the Maghreb countries.

Libya

A report released by the United Nations in November 2015 warned about Daesh beefing up its military presence in Libya; indeed, the northern African state is strategically important to Islamists due to its geographical location at the crossroads between the Middle East, Africa and Europe. The report cited Abu al-Mughirah Al Qahtani, the so-called “delegate leader” of Daesh’s Libyan Wilayat, who said that “Libya has a great importance because it is in Africa and south of Europe. It also contains a well of resources that cannot dry. […] It is also a gate to the African desert stretching to a number of African countries.”

While Daesh’s primary objective in Libya is to establish its control over the country’s oil exports, it also could make huge profits in arms smuggling: the destruction of the state following the NATO intervention has resulted in uncontrolled weapons’ supplies within the Libyan borders and beyond. Moreover, it may gain access to the banking operations in Libya, in the context of the ongoing dual power in the country: on one hand the elected parliament sitting in the city of Tobruk, on the other the pro-Islamic universal national congress based in Tripoli.

According to most analysts, Libya is the typical case of the ‘Arab Spring’ effect, the fact that the overthrowing of the secular Arab dictators like Muammar Gaddafi would create a huge security vacuum that would be filled the strongest and most violent actors. Greek security analysts cited as early as March 2011 Muammar Gaddafi’s second son, Saif Al-Islam, who warned that Libya “could become a ‘second Somalia,’ afflicting the Mediterranean with the scourge of piracy and bringing more opportunities for terrorists to attack European targets.”

In 2014, Daesh announced three provinces/governorates in Libya, namely, Wilayat Tarabalus/Tripolitania (including Tripoli and Sirte), Wilayat Barqa (Cyrenaica, including Derna and Benghazi) and Wilayat Fezzan (south).

These governorates likely coordinate their activities internally and may even operate under a unified command. The Libya wilayats are Daesh’s strongest source if it loses control of urban centers in Iraq and Syria. Daesh’s forces in Libya control the cities of Derna and Sirte, conduct governance activities, and run training camps. The Libya wilayats are gaining strength primarily by convincing local groups to align with Daesh ideologically and adopt its style of warfare.

The Wilayat Tarabalus is considered to be the most important and is the only affiliate now operating under the direct control of the central Daesh leaders.

Former Daesh prisoners in Sirte reported that the fighters and guards seem to be coordinated by a Saudi administrator, or “wali” sent by Daesh to preside over the city. (According to locals, Daesh periodically rotates in new administrators, who typically are from the Persian Gulf). Whenever drones were heard flying overhead, guards would run to the Saudi, take away his cell phone, and hurry him away to safety, considering him important enough to be a target of the U.S. airstrikes. However, the Daesh fighters in Sirte were commanded by Iraqis more powerful than the Saudi. The former prisoners also mentioned that Daesh seemed to command a strong intelligence network in Misurata, since their interrogators asked well-informed questions about their families and personal histories.

In Libya, Daesh is taking advantage of the civil war, receiving from the various factions that have taken over whatever remains of the Libyan government, weapons and other support from the oil wealth that should belong to the Libyan state.

While Daesh fighters are attacking both of the country’s rival governments with bombings and assassinations, the Libyan Central Bank continues to pay for public budgets and payrolls across both governments and the Daesh territory. Sirte residents, including the Daesh fighters, drive into Misurata to cash checks and buy fuel and other supplies.

Through a web of apparently contradictory local alliances, the jihadists have even been able to tap into a line of weapons and funding through the Misurata-dominated government in Tripoli and its allies among the Benghazi militias, even as it continues to attack that faction in Tripoli, Misurata and elsewhere.

One of the point men responsible for obtaining the money from the Tripoli government and buying weapons for the Benghazi militias, including the Daesh fighters is Wissam bin Hamid, well known for his ties to hard-line Islamist groups, who was the leader of Benghazi’s most formidable fighting force at the time of the deadly assault on the United States diplomatic compound in Benghazi in 2012. Wissam Bin Hamid maintained good relations with all of the factions, including Daesh, his only goal being to defeat his main adversary, General Khalifa Hifter, the strongman in eastern Libya.

In December 2015, Daesh accelerated its efforts to boost its presence in Libya, as part of its regional strategy aimed at easing pressure on its “caliphate” in Syria and Iraq. According to “Jane’s” analysts, Daesh has turned Sirte into its de-facto capital in Libya, replicating similar efforts at establishing its governance in Syria and Iraq. Daesh considers Libya as the most favorable country where a regional hub of its North African “caliphate” could be established. Daesh’s strategy is aimed at provoking a Western military intervention, especially on the ground, in Libya. An intervention would ease the military pressure on Daesh in Syria and Iraq. It also gives the group a more resilient alternative base.

No matter which scenario occurs, the outcome is the same: Daesh might become master of a country that’s around 300 miles from Sicily. Also, there is real concern that dynamics in Libya could destabilize neighboring states like Algeria which, like Egypt, has had a long and particularly violent battle with extremism. Radicals from neighboring countries have been using Libya as a refuge and a base for operations against their home countries.

Tunisia

Tunisia is the most affected country by Daesh’s presence in Libya, because its control of the cities and regions in Libya will destabilize Tunisia, and make it vulnerable to a danger that it is not yet prepared to counter. The risk of Daesh infiltrating the Tunisian border is facilitated by local armed groups supporting al-Qaeda, such as Ansar al-Sharia and Uqba ibn Nafaa. Equally worrying is the rise in the number of Tunisians fighters in Syria and Iraq to 3,800 members, according to Tunisian Interior Ministry estimates. The Tunisian Interior Ministry recently confirmed that hundreds of Daesh Tunisians fighters have returned to their country and are active as sleeper cells, while some of them joined the ranks of Ansar al-Sharia.

At least 1,500 Tunisian fighters are currently in Libya, trained and armed, and they undoubtedly would like to return to their country. It seems difficult for the Tunisian army, which has limited armament, to impose strict air and ground control on the common border, stretching over 500 kilometers (about 310 miles).

The suicide gunmen attack on the Bardo Museum in Tunis on March 18, 2015, claimed by Daesh, demonstrated a confluence of Daesh and al-Qaeda elements in North Africa. While both groups recruit heavily from Tunisia, the al-Qaeda affiliated Uqba Ibn Nafaa Brigade is the country’s strongest operational extremist group. The Bardo attack indicated that Daesh-linked elements likely played some role in the operation.

Members of the Daesh network likely intend to gain a following by launching more spectacular and lethal attacks in Tunisia. This assessment was strengthened on March 20, 2015, when Tunisian authorities intercepted a Daesh cell that planned attacks in multiple cities across the country. Daesh and al-Qaeda’s differing target types in Tunisia suggest that the groups’ efforts to cooperate with each other may increase rather than cancel each other out.

The worst-case scenario for Tunisia is the escalation of the violence in Libya, which would push hundreds of thousands of civilians to migrate toward Tunisia, in a replay of the 2011 scenario during the NATO’s military campaign against Gaddafi. The Tunisian state, which has been weakened by four years of instability and the collapse of its economic resources, is unable to bear the burdens of receiving a million refugees, in addition to tens of thousands of foreigners already living in Libya, such as what happened four years ago. Tunisia already accommodates nearly 2 million Libyans.

Morocco

With a Muslim majority population, high youth unemployment and its proximity to territory held by Daesh in Libya, Morocco is facing a rising threat of Islamic radicalism and terrorism that could shatter its image as trouble-free. A growing number of Moroccans are joining Daesh on the battlefield in Iraq and Syria, while several hundred others have traveled to Libya in recent months. Terrorism and political experts said these Moroccan fighters pose a threat to the greater Maghreb region as well as nearby southern Europe because they could mount attacks upon returning home.

So far Morocco has remained relatively terror-free, compared to its North African neighbors. There are departments within the religious affairs ministry that oversee the country’s 50,000 mosques and strictly monitor religious education to curb the spread of radical ideologies. The kingdom also is working closely with its allies, particularly the United States, Spain and France, to jointly fight global terrorism. However, terror threats in Morocco have become more frequent, as Islamic radicalism has spread throughout North Africa.

Moroccan authorities arrested thirteen individuals linked to Daesh in nine cities across Morocco on March 22, 2015. Officials claimed that the individuals constituted a group that was “in permanent contact” with the Daesh leadership, received foreign funding, and had named itself “The Islamic State in the Western Maghreb.” The cell had reportedly smuggled in weapons from the Spanish territories of Ceuta and Melilla and was planning a series of assassinations targeting Moroccan military and political figures. Moroccan authorities also arrested five members of a Daesh-linked operational cell in Nador on April 13, 2015. The group worked with an individual who was planning an attack in the Netherlands, highlighting Morocco’s location as a pathway connecting Europe and North Africa.

Most recently, on January 8, 2016, seven suspected terrorists who allegedly had received training from Daesh in Syria and were planning attacks on Moroccan soil were arrested in Casablanca.

While Morocco still cannot be compared to war-torn Libya, where Daesh controls the coastal city of Sirte and has seized key oil ports on the Mediterranean coast, terrorism experts said the country is becoming more and more vulnerable as Daesh looks to expand its influence on Europe’s doorstep. Radicalized Moroccans could launch attacks or recruit jihadists at home or even in southern Spain, which is narrowly separated from Morocco by just 8 nautical miles (Morocco also shares a western border with the Spanish territory of Ceuta and Melilla).

Algeria

Daesh’s Wilayat al-Jaza’ir (Algeria) is the least active of Daesh’s wilayats. Nevertheless the group released statements which claimed small attacks on Algerian security forces. Algerian media attributed some of the attacks to Jund al-Khalifah in Algeria (JKA), an al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) splinter group that pledged allegiance to Daesh in September 2014 and likely constitutes the primary membership of Wilayat al-Jaza’ir. This claim, as well as reports of a JKA cell dismantled on March 22, 2015 indicates that remnants of the organization may still be active despite the Algerian government’s December 2014 counterterrorism offensive. Under the umbrella of Wilayat al-Jaza’ir, Daesh also retains historic networks in the country that are likely connected to pro-Daesh elements in Tunisia.

In spite of the relatively small-scale Daesh activities of its territory, Algeria is considered one of the countries with a high risk generated by Daesh’s expansion in western Libya, which make the Algerians to strongly oppose any military intervention in Libya, whether at the international or the Arab level.

While Algeria has an experienced army and sophisticated military equipment, unavailable to its neighbors, there is no guarantee that Algeria would remain safe in the face of Daesh expansion and infiltration into its territories, as it is not possible to monitor the long border it shares with Libya. The joint military command set up by Niger, Mauritania, Mali and Algeria has also proved to be inefficient.

Other Daesh African aims

Perhaps hoping to sustain its image of invincibility, Daesh’s propaganda has increasingly promoted the operations of its foreign affiliates. Western intelligence agencies say it is devoting more resources to them as well.

The expansion in Africa is favorable for Daesh due to poverty, political conflict, continual sectarian tension and the illegal spread of weapons. This supports its ambitions to extend the so-called caliphate from the Levant to the land of Egypt, the land of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and to the Maghreb, according to a map of the caliphate published by the group on its social media sites.

a) The Egyptian branch of Daesh, deemed second after Libya’s in the scale of its threat, had a long record as a domestic insurgency before pledging its allegiance. The branch appears to have acted on its own initiative to carry out the bombing of the Russian charter jet on October 31, 2015, according to Western intelligence. The Daesh core immediately embraced the bombing, which killed 224 people, trumpeting the achievement of its Egyptian “brothers.”

Daesh is seeking to implement its plan through specific tools such as Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, which seeks to control Egypt. It would use Boko Haram to control the depths of African and the headwaters of the Nile.

b) According to Veryan Khan, editorial director for the Florida-based Terrorism Research & Analysis Consortium (TRAC), which tracks international terrorism and had a source on the ground in Mauritania, Daesh, Boko Haram and Al-Qaeda have links to two camps in this North African country, which shares a border with Mali and is not far from Nigeria, where Boko Haram is based.

At least 80 trainees, recruits from the United States, Canada, and parts of Europe, including France, are known to be training at the camps, which are far from the population centers. Besides the two training camps, there are about 7,000 mosques and 1,000 madrassas, or Islamic religious schools, in Mauritania, but the Mauritanian government monitors very few, creating opportunities for these institutions to be used as propaganda and training centers.

In December 2014, Mauritanian security forces arrested four Daesh terror suspects in Zouérate, the largest town in northern Mauritania, who claimed Daesh was “on its way to that country.”

With Boko Haram in Sub-Saharan Africa

Boko Haram’s leader Abu Bakr Shekau pledged allegiance to Daesh leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi on March 7, 2015, confirming rumors of growing contact between the organizations. Al-Baghdadi accepted Shekau’s allegiance and renamed the group as the Islamic State’s Wilayat West Africa. In the next two months, ten other Daesh wilayat in Algeria, Libya, Yemen, Syria and Iraq issued videos praising Shekau’s allegiance, and Wilayat West Africa became the most significant of Daesh’s more than 30 claimed wilayat in terms of number of militants, territory controlled, and operational capacity.

While the Daesh leadership celebrated the pledge, it chose not to establish a wilayat in Nigeria immediately.

Daesh has a standardized wilayat creation process which was detailed in a February 12, 2015 publication. Prospective affiliates must document their allegiance, unite under a collectively chosen leader, and present a military and governance strategy to Daesh for approval in order to be officially recognized as a wilayat. Daesh does not permit anyone to announce a wilayat or pose as representatives of Daesh until this process concludes. It thus requires internal unity and strategic cooperation from its wilayats.

Daesh’s choice to delay a declaration of a wilayat in Nigeria suggested that the operational relationship with Boko Haram might be limited. While Daesh publications on March 31 and April 23 2015 referred to a “Wilayat Gharb Afriqiya (West Africa)”, they did not confirm that Daesh leaders have officially designated a wilayat in Nigeria. However, Daesh used Boko Haram’s pledge as an opportunity to announce its intent to “rule” Africa, a choice that increases the stakes for Daesh’s strategic competition with al-Qaeda.

While Daesh’s impact on Wilayat West Africa is most easily seen in media and propaganda (and, of course, Boko Haram’s new name), an operational relationship exists and, according to a source with a record of inside knowledge, in the Daesh hierarchy Shekau reports to a new overall emir of Wilayat West Africa, who is a Libyan and former Mali-based militant in Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s al-Mourabitoun. Nonetheless, Daesh recognizes Shekau as the titular head, or wali, of Wilayat West Africa.

Joining forces with Libya

As Daesh claims of Wilayat West Africa operations in Chad were released in July 2015, there were also reports in north and west Africa that Wilayat West Africa militants were mixing with Daesh in Libya. By August 2015, a trend started to become apparent of growing interactions and greater trust between Wilayat West Africa and the wilayat in Libya, which would further integrate the Wilayat West Africa into the broader “Islamic State” system.

For example, several Daesh supporters in Barqa wrote on twitter that “Shekau’s followers” traveled to Darna (a city near Barqa in eastern Libya) to support Daesh and these reports were consistent with other reports from Libya that 80 to 200 Wilayat West Africa militants were in Sirte.

Nigerian media also reported that the country’s military intelligence believed Shekau fled to North Africa and that Wilayat West Africa now reports to Syria or Iraq in the Islamic State hierarchy.

Algerian security forces also believe Wilayat West Africa is active in northern Niger, which borders Libya, together with 200 militants from MUJAO (MUJAO’s leader pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi in July 2015 against Belmokhtar’s wishes, thus leading to a break-up among al-Mourabitoun militants). The openness of migration routes from Nigeria through eastern Niger to Libya makes travel between the two wilayat fairly straightforward, and Daesh can easily afford to pay smugglers to carry militants (and weapons) along that route.

The movement of Wilayat West Africa militants to Libya has the potential to transform the “Islamic State landscape” in northwest Africa in at least three ways.

First, it could allow Wilayat West Africa to forge deeper and more operational ties with Daesh beyond the media relationship.

Second, Wilayat West Africa could acquire new militant training and skills from Daesh’s militants. Negotiators who have been in Wilayat West Africa camps say that Chadians who were formerly mercenaries for Muammar Gaddafi in Libya joined forces with Wilayat West Africa and operate its complex machinery, such as tanks stolen from the Nigerian army.

Third, Wilayat West Africa and the Libyan wilayat can coordinate attacks in Nigeria and the Lake Chad sub-region. Daesh will likely also continue to encourage Wilayat West Africa to carry out attacks throughout the Lake Chad sub-region to demonstrate that it is a “West African” and not a “Nigerian” movement.

Daesh’s need to rival Belmokhtar’s al-Mourabitoun, whose area of operations is still mostly in Mali and Niger but potentially could reach Nigeria, will likely accelerate Wilayat West Africa’s importance in the context of the overall Daesh versus al-Qaeda global rivalry.

Becoming “West African” and re-creating Kanem-Bornu

One trend to watch out for is how Wilayat West Africa manages its identity as a “West African” – as opposed to Nigerian – militant group. Observers assess that the Malians, Mauritanians, and Algerians in MUJAO might merge into Wilayat West Africa (possibly with MUJAO’s leader responsible for the Sahel and Shekau responsible for the Lake Chad sub-region). Furthermore, Wilayat West Africa’s overall leadership in Libya that reports to Syria will further dilute its Nigerian-ness.

One final way the re-branding of Boko Haram as a “West African” movement could prove instrumental is if the Nigerian military succeeds and wins the war against “Boko Haram.” In such a case, Wilayat West Africa could attempt to hold territory in Nigeria’s weaker neighbors, such as Diffa, Niger, northern Cameroon, or an increasingly insecure northern Mali. The brand “Wilayat West Africa” may then serve Boko Haram in the same way that the brand “Islamic State” can serve al-Baghdadi’s militants if, for example, Daesh is defeated in Syria and Iraq and its “core” relocates to the “third capital”, Sirte (Libya). Then the “core” would be able to maintain the master narrative of “remaining” and “expanding” to Libya, while also becoming a closer neighbor of its Wilayat West Africa brethren.

Although it suffered major territorial losses in Nigeria, Wilayat West Africa is a far from finished force and can still engage in asymmetric warfare. The next phase of the insurgency in Nigeria and the Lake Chad sub-region will likely feature a Wilayat West Africa determined to re-establish enough territorial control to support the narrative that it has a “state”.

One of the Daesh/Wilayat West Africa strategies may aim to re-create the Kanem-Bornu African trading empire, which had a territory that included modern-day southern Chad, northern Cameroon, north-eastern Nigeria, eastern Niger, and southern Libya. Toward the end of the 11th century, Kanem-Bornu became an Islamic empire, when its leader, Ibn ʿAbd al-Jalīl, converted to Islam until the empire faded out between 1846 and 1893.

Since its pledge of allegiance to Daesh, Boko Haram has expanded its campaign across the borders of the old Kanem-Bornu Empire; namely, Northern Nigeria, Cameroun, Niger, and Chad. Although it started its campaign from northeastern Nigeria, the group is neither national nor international: its strong ethno-linguistic cross-border ties facilitate cross-border movements.

In the last years, Boko Haram continued to intensify cross-border activities and its territorial ambitions have expanded beyond Nigeria to territories of the old Kanem-Bornu Empire. It enjoys the historic ethnic, linguistic, and cultural ties created by the old Kanem-Bornu Empire, particularly the Sunni-Muslim interrelation of Kanuri, Hausa and Shuwa Arab groups that transcend national boundaries.

Consequently, Nigeria’s President Muhammed Buhari will prioritize cross-border military and political cooperation with Cameroon, Chad, and Niger to “encircle” Wilayat West Africa and prevent the militants from reclaiming their lost “Islamic State” in the Nigeria-Cameroon border region.

Intelligence analysts also point out that, if merged with Daesh, Boko Haram has the ability to achieve the dream of Daesh to extend the so-called caliphate to enter Ethiopia and the headwaters of the Nile.

Daesh’s Economic Aim: the West’s Energy Collapse

Since Daesh emerged on the scene in Syria in 2013, long before they reached Mosul in Iraq, the jihadis saw oil as a crutch for their vision for an Islamic state. The group’s Shura council identified it as fundamental for the survival of the insurgency and, more importantly, to finance their ambition to create a caliphate.

While al-Qaeda depended on donations from wealthy foreign sponsors, Daesh has derived its financial strength from its status as monopoly producer of an essential commodity consumed in vast quantities throughout the area it controls. Even without being able to export, it can thrive because it has a huge captive market in Syria and Iraq. According to the US Treasury, Daesh is making up to $40 million per month selling oil that is stolen from production facilities in Syria, and made up to $500 million in total so far from the oil trade. Also, attempting to run its oil industry by mimicking the ways of national oil corporations is part of Daesh’s strategy to project the image of a state in the making.

On the other hand, intelligence experts put Daesh’s recent Libya oil tanker attacks in connection to its plans to attack oil fields, pipelines and trucking routes in Libya and Sinai Peninsula that aim to increase its income, since the costs of its oil operations in Syria increased due to the air strikes on the oil transportation facilities that it controls.

Alongside its military and security operations and its sophisticated media output, oil is centrally controlled by the top Daesh leadership. It’s a central Shura matter and a centrally controlled and documented area.

Until recently, Daesh’s emir for oil was Abu Sayyaf, a Tunisian whose real name, according to the Pentagon, was Fathi Ben Awn Ben Jildi Murad al-Tunisi, who was killed by U.S. special forces in a raid in May 2015. According to U.S. and European intelligence officials, a treasure trove of documentation relating to Daesh’s oil operations was found with him. The documents revealed a meticulously run operation, with revenues from wells and costs carefully accounted for. They showed a pragmatic approach to pricing too, with Daesh carefully exploiting differences in demand across its territories to maximize profitability.

Oversight of the oil wells is carefully controlled by the Amniyat, Daesh’s secret police, who ensure revenues go where they should and mete out brutal punishments when they do not.

Libyan “disaster scenarios”

According to many experts, several scenarios are at play. In one of them, if Daesh gains control of Libya’s oil industry, it will possess sufficient revenues to consolidate power and become a persistent problem in Libya (a self-funded organization, which controls territory and is able to subjugate a population).

At the same time, by destroying or crippling Libya’s oil industry, Daesh might scuttle a UN-brokered power-sharing agreement between the three non-Daesh factions in the Libyan civil war (that is supposed to result in a unity government), since a key part of that agreement is how the factions will divvy up oil revenues.

If the power-sharing agreement becomes a reality, about 6,000 Western soldiers and marines, including from Britain, France and the United States and led by Italy will be sent to the country to help the new government survive.

In the beginning of January 2016, the British Daily Mirror reported that the British Special Air Service (SAS) have been deployed in Libya waiting for the arrival of almost 1,000 British military personnel. SAS units, including military close observation experts from the Special Reconnaissance Regiment, have been sent to Libya to advise Libyan commanders on battlefield tactics. They also are gathering intelligence on the military situation in the country. Such intelligence will be the base for Britain’s chief of joint operations, Lt. Gen. John Lorimer, to decide whether to request the presence of more warplanes of the Royal Air Force (RAF) in nearby Cyprus, which serves as an RAF base for the kingdom’s operations in Iraq and Syria.

While Daesh would welcome a chance to kill European troops on the soil of a Muslim country, ruining the UN-sponsored power-sharing agreement would likely keep the Europeans out, giving Daesh more time to set up a new government based on an ultra-orthodox interpretation of Sharia law.

Critical consequences for Europe

Daesh in Libya has been depicted as posing a new trans-Mediterranean terrorist threat to the West, particularly via Italy and Greece. This threat has fueled calls for a military intervention or at least a coastal blockade. Yet it is not even necessary for Daesh to reach European shores to still pose a major new threat to Western interests, economy and regional stability.

Daesh has already threatened to use Libya and North Africa to disrupt European security and economic wellbeing, including the aim to cut natural gas supplies of France, Italy and Spain. In an issue of Dabiq, its English-language propaganda magazine, the leader of the Daesh affiliate in Libya vowed that “the control of Islamic State over this region will lead to economic breakdowns especially for Italy and the rest of the European states.”

Daesh’s moves against Libya’s oil infrastructure have significant economic consequences in Europe, since before the 2011 uprising against the Gaddafi regime Libya provided 11% of Europe’s oil needs. In 2014, Europe imported only 3.4% of its oil from Libya. Libya has the potential to become again a significant exporter to Europe, but this would not happen if Daesh moves against the country’s oil fields.

NATO European member states have been increasingly concerned about Daesh gaining ground in Libya. France’s Le Figaro reported in late December that France is considering a plan for intervention in Libya to eradicate “the cancer of Daesh” as well as its metastases. Citing the French Defense Ministry the journalist pointed out that a six-month military operation would possibly be launched against Daesh in Libya before spring.

On the other hand, pessimistic scenarios stress that a series of Paris-style attacks across Europe could fracture the European Union, as individual countries close their borders and pursue different national approaches to the threat of Islamic extremism at home and abroad. The Syrian refugee crisis has already placed enormous strains on European unity. If jihadists motivated by the successes of Daesh abroad succeed in terrorizing the major capitals of Europe in a systematic way, existing transnational institutions may simply buckle. The EU would likely remain as a shell institution, but decades of integration could finally be reversed.

Case Study: Somalia

According to many experts and observers, among the dysfunctional states in Africa that would be easy prey for Daesh’s expansion, Somalia is the first, due to the ethnic and religious divisions and the weakness of the government’s authority.

There are also Somalia’s neighboring countries, such as Djibouti and Sudan, where suppression and oppression, poverty and lack of development prevail. Thus, central and northern Africa might become the new headquarters for Daesh’s networks, which were joined by several jihadist movements that move easily between states without being tracked by the security services since there is no security coordination between these countries to confront them. A catastrophic scenario is generated by these countries’ inability to face Daesh, which might expand into the depths of the African countries and take advantage of a suitable environment for the formation of a jihadi republic, a Daesh republic or an Islamic caliphate.

Daesh fighters already call war-torn Somalia the “little emirate”; it holds potentially huge rewards for the extremist group: it is an almost non-governed, secession-plagued country, but with significant and so far untapped natural resources. It also has a strategic position in the Horn of Africa, with the continent’s longest coastline, and it borders three U.S. allies: Ethiopia, Djibouti and Kenya.

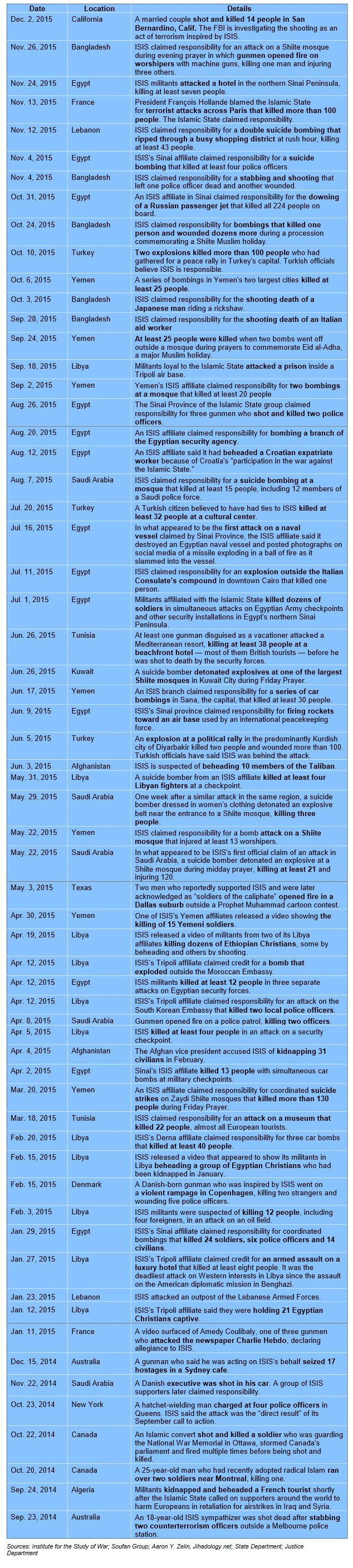

The main area targeted by Daesh is forms by Somalia’s splitting regions of Somaliland and Puntland, especially the Berbera port. Local observers do not exclude a competition or a conflict al-Qaeda vs. Daesh in the country.

Untapped resources

Somalia has untapped reserves of numerous natural resources, including uranium, iron ore, tin, gypsum, bauxite, copper, salt and natural gas. Due to its proximity to the oil-rich Gulf Arab states such as Saudi Arabia and Yemen, the nation is also believed to contain substantial unexploited reserves of oil.

A survey of Northeast Africa by the World Bank and U.N. ranked Somalia second to Sudan as the top prospective producer. In 2012, the administration of former president of Puntland, Abdirahman Farole, gave the green light to the first official oil exploration project in Puntland and Somalia at large.

In the late 1960s, UN geologists discovered major uranium deposits and other rare mineral reserves in Somalia. The find was the largest of its kind, with industry experts estimating the deposits at over 25% of the world’s then known uranium reserves of 800,000 tons. Besides uranium, an unspecified quantity of yttrium, a rare earth element and costly mineral, was also found in the country.

The splitting of Somalia and the Islamist role

From the strategic point of view, Somalia had always been recognized as highly important. Its President Siad Barre had played favorite to both the Soviets and the United States at different times, even allowing U.S. Rapid Reaction forces to establish a base there. In 1982, General Alexander Haig emphasized the strategic significance of Somalia to the U.S. saying the country “would be vital to our own Persian Gulf access.”

Eventually, the U.S. cut aid to Somalia in 1989 and in January 1991, Siad Barre was overthrown by his Defense Minister, General Mohammed Farrah Aideed, a Somali nationalist. The U.S. Embassy was burned to the ground as Somalis expressed their outrage at decades of U.S. support for the brutal Barre.

This prompted the launching in Somalia of the UN operation Restore Hope with troops from Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Egypt and Nigeria participating. The Saudis too sent elite forces. The UN led effort soon became a hunt for Mohammed Farah Aideed, and resulted in a failed political mission and the departure of all US troops after the infamous Blackhawk Down incident. The UN pulled out of Somalia in 1995; its effort failed to create a new national government and end the reign of the warlords, who continued in power throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century.

During the humanitarian crisis, the Rome-based World Food Program, which Iraq had found was serving as a CIA cover, chartered two C-130 transports from CIA-contract airline Southern Air Transport and began delivering food to Somalia. In fact, the CIA began arming Islamic fundamentalists bent on destroying Aideed’s leftist Somali National Alliance.

As the fighting intensified the 2,000 U.S. Marines who had officially been deployed to protect UN peacekeeping troops prepared to come ashore. UN relief groups were forced to withdraw their workers from the Somali regions of Bardera and Baidoa where the famine, which served as pretext for intervention, was worst.

General Aideed tried to form a government but was forced to fight off the Islamist extremists which the CIA supported. The day the U.S. Marines came ashore to back the extremists, President George Bush stated that the war “may have to be extended” into northern Somalia. The U.S. backed the Somalia National Movement’s successful attempt to seize northwestern Somalia and declare an independent country called the Republic of Somaliland.

In northeastern Somalia, which includes the strategic Gulf of Aden ports of Berbera and Boosaaso, the CIA supported the separatist Somali Salvation Democratic Front, which had called for foreign intervention in Somalia.

Eventually the two northern factions seceded from Somalia and created two new “countries” known as Somaliland and Puntland, bordering the Gulf of Aden and the strategic French-controlled country of Djibouti at the gateway to the Suez Canal.

All the while the Clinton Administration attempted to frame the Somalia conflict as an ethnic struggle between different clans, a characterization which they would use to justify adventures in Rwanda and Yugoslavia as well.

As Somali support for General Aideed grew, the U.S. media did their best to demonize him. In 1996, General Mohammed Farrah Aideed lost his game, supposedly being gunned down by CIA-backed Islamist assassins. However, it was Aideed who benefitted from the activities of al-Qaeda in Somalia, which are alleged to have begun as early as 1992, when Ali Mohamed and other al-Qaeda members purportedly trained forces loyal to him.

The Islamic Courts (al-Shabaab’s predecessors) briefly seized power from the warlords in Mogadishu and most of southern and central Somalia until they were ejected by Ethiopian forces at the end of 2006. Ethiopian troops remained in Mogadishu until early 2009 when the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), were strong enough to replace the Ethiopians.

Ethiopian and AMISOM forces both struggled to counter al-Shabaab, which in 2011 was pushed out of Mogadishu and other key towns, but moved its forces to rural southern and central Somalia. Kenyan troops entered southern Somalia in 2011 to remove al-Shabaab from the Lower Juba and formally became part of the AMISOM force in 2012. Ethiopian troops, who periodically crossed into Somalia from across the Ethiopian border, became part of AMISOM in 2013.

Currently, Somalia is trying to create a federal-style government, with expected elections for September 2016, and since Somali clans continue to prevail as the predominant political force, it will almost certainly result in some kind of federal system. Two recent visitors to Somalia, retired British Army Major General Dickie Davis and head of the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst Foundation, Greg Mills, concluded that the state operates today as a clan-based mafia where entwined business and political interests feed off each other. Others describe the current government as disjointed and widespread corruption as a way of life.

Somaliland and Puntland: connections with the Islamists

In 2010, reports surfaced linking the secessionist government of the northwestern Somaliland region with the Islamist extremists that are currently waging war against the Transitional Federal Government and its African Union allies. The International Strategic Studies Association (ISSA) published several reports shortly after the 2010 presidential elections in Somaliland, accusing the enclave’s newly elected president Ahmed M. Mahamoud Silanyo of having strong ties with Islamist groups, and suggesting that his political party Kulmiye won the election in large part due to support from a broad-based network of Islamists, including al-Shabaab. The ISSA also described Dr. Mohamed Abdi Gaboose, Somaliland’s new Interior Minister, as an Islamist with “strong personal connections with al-Shabaab”, and predicted that the militant group would consequently be empowered.

In January 2011, Puntland accused Somaliland of providing a safe haven for Mohamed Said Atom, an arms smuggler believed to be allied with al-Shabaab. Somaliland strenuously denied the charges, calling them a smokescreen to divert attention from Puntland’s own activities.

Map of Somalia and its splitting territories

The Puntland Intelligence Agency also claimed that over 70 Somaliland soldiers had fought alongside Atom’s militiamen, including one known intelligence official who died in battle. Somaliland media reported in January that Atom’s representative requested military assistance from the Somaliland authorities, and that he denied that Atom’s militia was linked to al-Shabaab.

Puntland government documents claim that Atom’s militias were used as proxy agents in 2006. They accuse Somaliland of offering financial and military assistance to destabilize Puntland and distract attention from attempts to occupy the disputed Sool province.

Berbera: a high prize

Somalia’s splitting region of Somaliland is targeted by Daesh because of its port of Berbera, which was the only major Indian Ocean base for the Soviet Union, until November 1977 when Moscow decided to take sides with Ethiopia during the Ethiopia-Somalia war.

Leaving Berbera in 1977, the Soviet Union lost its big port equipped with a mooring, an important communication center, which was eventually transferred to Aden suburbs in the then existing South Yemen, a tracker station, a tactical missile warehouse, as well as a big fuel storage and accommodation facilities for one thousand fifty people.

In the ‘980s Berbera was considered by the U.S. Navy as the best suited for American purposes, since the Soviet Union had built a 3,200-foot runway and, on departing, left a number of buildings that could be converted for the use of American naval and air forces. At the same time, the port of Berbera was considered as a “major port” also by the Central Intelligence Agency.

Intelligence analysts estimated at that time that from Berbera, aircraft and ships would be able to survey the entrance to the Red Sea and the Soviet installations in Aden, Southern Yemen. It would also serve as a backup base for any military facilities used by the Navy and Air Force in Oman, which is to the northeast and closer to the Persian Gulf.

The increased presence of Russia in the anti-Daesh war and in the region also fuelled talks about the possibility to offer Moscow the facilities of Berbera for the Russian submarines. One such discussion was started on a Somaliland forum in December 2015.

A fruitful recruiting campaign

While Daesh’s presence in Somalia still appears to be small, its bid for followers there shows its ambitions. In early 2015, Daesh released a series of videos that aimed to win recruits, particularly from within al-Shabaab. The videos feature heavily armed men who appear to be of Somali ethnicity.

In March 2015, Daesh reached out to al-Shabaab in a bid to expand its reach and influence beyond its base in Iraq and Syria, part of a wider plan to realization of its caliphate. According to the local police, there are Daesh recruiters in the country trying to lure young men, especially college and university students in to the rank and file of the group.

The recruiting campaign in Somalia has paid some dividends. In October 2015, an influential Muslim cleric, Abdiqadir Mumin, announced that he had joined the group and was bringing at least 20 of his followers with him. Other reports even mentioned that Puntland was declared a wilayat (district) of the Islamic State.

Mumin is a cleric with an international following; he was seen as one of al-Shabaab’s most significant religious figures and a leader in his native Puntland province, which is considered to be outside of al-Shabaab’s heartland.

Additionally, 27 fighters from Somalia, though it’s unclear if they were members of al-Shabaab, have also appeared in a Daesh video and gave their allegiance to Daesh on 8 November. Further, on 8 December, another group of Somali militants, allegedly al-Shabaab members, led by an individual identified as Abu Nu’man Al-Yintari, gave their allegiance to Daesh in a video.

A radical Kenyan cleric named Hussein Hassan, once aligned with al-Shabaab, also has recently recorded an audio message suggesting that al-Shabaab join Daesh. Underscoring the risk, Kenya’s police chief told the Associated Press that about 200 al-Shabaab fighters had joined Daesh and that the group was operating near Kenya’s border.

According to the Kenyan police, in late 2015 the group has deserted to create Daesh affiliate in Eastern Africa. Reports mentioned that Al-Shabaab has undergone a split, with one group staying loyal to al-Qaeda and the other, predominantly foreign, group swearing allegiance to Daesh. The two groups are competing to spread an international jihadist agenda, and have engaged in a sort of recruiting rivalry that has apparently led to the increased violence in Kenyan towns near the Somalia border. The two groups appear to have carved out individual operating areas, with the Daesh-affiliated group operating in Kenya’s northeast, and the al-Qaeda affiliate operating from Kenya’s southern forest region as a staging point.

Daesh’s presence in the splitting regions of Somalia (Somaliland and Puntland) was reported in September 2015, when complaints from local families mentioned that Daesh was abducting children in the port of Bossasso, with around 40 children missing.

Accounts from local residents in the Sanaag region suggested that a boat carrying around 40 abducted children approached at Dur-Duri, near the Laasqoray port, in the first incident of this kind involving Daesh.

Daesh – al-Shabaab: a difficult relationship

For Daesh, there are several benefits from an alliance with al-Shabaab. Having established its branch in neighboring Yemen, Daesh may be able to create a safe haven in Somalia as well as passage for its fighters to cross back and forth from the Middle East via the Gulf of Aden to Africa via the Horn of Africa.

In addition, its location in the Horn of Africa has considerable importance for trade routes through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, piracy being one of the issues faced by vessels travelling through those routes. If Daesh were to secure the Horn of Africa and exploit piracy, it may benefit economically as well as strategically by targeting vessels.

Daesh’s expansion into Somalia is to find organized local groups and seed them with resource and training to pursue systematic violence. Al-Shabaab is an effective military organization; therefore merging with the group will shape local conditions and prepare the ground for Daesh’s future expansion into the rest of the Horn and East Africa.

However, despite Daesh’s persistent attempts to pull al-Shabaab into its ranks, al-Qaeda still holds sway over the Somali group, given al-Shabaab’s history and al-Qaeda’s presence in Somalia.

Having trained with the Taliban in Afghanistan, Ahmed Abdi Godane, the former leader of al-Shabaab had been associated with Osama bin Laden. Al-Qaeda’s presence in Somalia can be traced back to the early 2000s while senior al-Qaeda members have worked alongside al-Shabaab since its official formation in 2006. In this respect, al-Qaeda has a marked advantage over al-Shabaab, compared to Daesh. Following the death of Godane, who was killed in a US drone strike on September 1, and the appointment of Ahmed Omar Diiriye, aka Abu Ubaidah, as the new leader, the group promptly reaffirmed its allegiance and loyalty to al-Qaeda. Little is known about Ahman Omar, except that he earned the reputation as a brutal punisher of non-Muslims.

However, Al-Shabaab has been suffering from a power struggle in its leadership even before its merger with al-Qaeda in 2012. With deep clan loyalties in Somalia, al-Shabaab has been having difficulties advancing a unified cause. It has long been divided between leaders whose interests are nationalistic, others who desire to rule Somalia under the Sharia law, and yet others who are faithful to al-Qaeda’s vision of global jihad. Also, the group’s foreign recruits, especially those from Kenya and the United States, have been viewed as potential spies. In addition, tensions between clans have diminished al-Shabaab’s support in the country, making the group’s members even more vulnerable to Daesh’s recruitment drive.

The reason for which al-Shabaab may eventually join hands with Daesh is to obtain a much-needed financial lifeline at a difficult time, following a string of losses in the territory it holds and the decimation of its top leadership. For its part Daesh would benefit from al-Shabaab’s allegiance by its establishment in the strategic Horn of Africa. However, the likelihood of Al-Shabaab abandoning its allegiance to Al-Qaeda remains low even if there are individual cases of fighters defecting to and supporting Daesh.

Adapting counter-terrorism operations

The rise of Daesh in northern Africa, but also the need of continuing surveillance in Somalia and the Horn of Africa region generated a reorientation of the U.S. counter-terrorism operations, mainly by moving its drone operations from southern Ethiopia as demands expand elsewhere across the continent with the rise of Daesh in Libya, and extremist militants in Nigeria, Mali, Chad and Cameroon. The move was announced at the beginning of 2016, and it was also announced that some of the tasks of the drone operations are expected to be undertaken by the drone U.S base in Djibouti, which operates as the U.S. main combat hub for counterterrorism efforts in the Middle East and the Horn of Africa.

Since 2011, the U.S. had been using the air base in Arba Minch, 250 miles south of the Ethiopian capital, to launch surveillance drones aimed at groups in East Africa with links to al-Qaeda, particularly al-Shabaab. Although State Department officials maintained that the move had nothing to do with bilateral differences between the U.S. and Ethiopia, some experts speculated that Addis Ababa may have had reservations about hosting the U.S. drones. The Ethiopian ruling party has also had to face some unrest in the Muslim community, where many believe the government interfered with the country’s official Islamic authority.

Some experts say the fight against al-Shabaab was going well enough that the Pentagon’s Africa Command (Africom), had the opportunity to redistribute its scarce resources elsewhere, since other groups are rapidly gaining strength. Among them, Daesh has consolidated its power in Libya and its presence has reportedly forced the U.S. to focus on gathering intelligence there in order to better monitor militant movements in North Africa.

Conclusion

According to counter terrorism experts, if Libya becomes a hub to sub-Saharan Africa, similar to Raqqa in its region, in 2016 or 2017, West Africa wilayat (Boko Haram) could also carry out a new type of attacks in Nigeria or West Africa under the training and coordination of Daesh in Libya. Experts also say that tighter control by Turkey of its border with Syria or setbacks for Daesh in Syria and Iraq could encourage would-be global jihadists to turn to Africa as a battlefront.

Although there are analysts who consider that the Daesh threat in Africa might be exaggerated by propaganda, the fact that terrorist movements in the African continent are pledging allegiance to Daesh warns about a dark scenario in which Daesh might create strong areas of influence and occupy vital and vast geographic areas in Africa.

Lt. Gen. Vincent Stewart, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, told the House Armed Services Committee in March 2015: “With affiliates in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, the group is beginning to assemble a growing international footprint that includes ungoverned and under-governed areas.”

In such a “dark scenario”, many evoke the 1453 AD moment, when the Ottoman Turks captured Istanbul from the Byzantine Empire and blocked the overland route from Europe to Asia that was critical for the spice and silk trade. The Europeans sought an alternative sea route to the East, around Africa and by 1498, 45 years after the fall of Constantinople, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama had rounded the Cape of Good Hope. Before long, the Europeans turned the refueling and replenishment stations for their ships on the way to the Far East into launch pads for colonial domination of the African hinterlands. Today, Asia is big again, with China as the world’s second largest economy and most populous nation, and with a resurgent India, the world’s second most populous nation. If Daesh and other extremist groups were to control the Middle East and North Africa, they would be able to block the two key trade routes for Europe to Asia, Africa, and the Americas: the Mediterranean and the Red seas.

It is conceivable that a few more Arab countries in the Middle East might collapse in the years ahead and the world powers might well live with that, especially if their oil is no longer important, and that would mean Israel would be imperiled too.

There would be no rear bases for the Americans and the Europeans to mount a defense of Israel. The only possibility would be in the Horn of Africa, which is what Daesh aims to control. Its aim is not only North Africa or the Horn, but the whole continent, which would give them the control of the sea routes between the Americas and Asia. Who does that would determine whether the Americas and Asia prosper.

The future of African cooperation in confronting the threat posed by Daesh depends on several factors. One of these factors is Egypt’s success against the Muslim Brotherhood and its ability to face Daesh in Libya and finally being able to form an alliance to counter terrorism in Africa (the African Alliance, which Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi had called for in February 2015). The second factor is related to extending the international coalition’s operations against Daesh from Iraq and Syria to include African countries such as Mali, northern Nigeria and Cameroon and assist these countries in confronting terrorism.

oooOOOooo

Annex

Daesh and Daesh-inspired attacks, September 2014 – December 2015

Check Also

Libya’s Fragile Peace Tested Again As New Clashes Roil Tripoli

Clashes broke out earlier in the week across several districts of the Libyan capital, reportedly …

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News