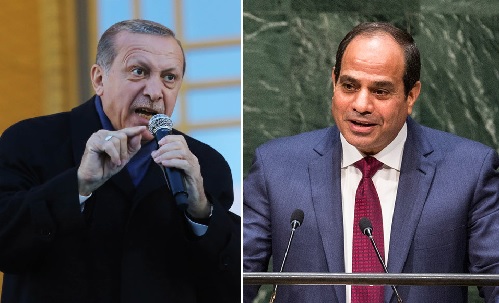

The picture sent shockwaves through Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s grassroots: A poor Egyptian member of the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan in Arabic) handcuffed by the Turkish police, put aboard a Turkish Airlines plane to fly back to Cairo, to be tortured and eventually executed. Is President Erdoğan not a staunch supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood? Is he not an eternal enemy of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who came to power after toppling the Ikhwan man, former president Mohamed Morsi, a darling of Erdoğan? Did Erdoğan not freeze diplomatic relations with el-Sisi’s Egypt?

In August 2013, about a month after el-Sisi toppled Morsi, Erdoğan appeared on television. In an unusually soft voice he read a letter written by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed al-Beltagy to his daughter Asmaa, a 17-year-old girl who had been killed in Cairo when security forces stormed two protest camps occupied by supporters of the deposed president, Morsi. Poor Asmaa was shot in the back and chest.

“I believe you have been loyal to your commitment to God, and He has been to you,” Asmaa’s father wrote in the letter. “Otherwise, He would not have called you to His presence before me.” You could see Erdoğan’s tears. In later days, Asmaa became another symbol of Turkish Islamists; Erdoğan cheered party fans with the four-finger Rabia sign, a reference to his solidarity with the Muslim Brotherhood, and a sign of his endearment to the unfortunate girl.

El-Sisi ran for president and won the elections, which Erdoğan then declared “null and void.” Erdoğan vowed never to recognize the regime that seemed to have come to power in Egypt through a coup, and called el-Sisi “an illegitimate tyrant” and a “coup-maker”.

Who, then, is Mohamed Abdelhafez Ahmed Hussein, the Muslim Brotherhood member deported to Egypt presumably for capital punishment, and why would the Turkish regime, which one would expect to be his staunchest savior, extradite him to a hostile regime?

Hussein, born on February 14, 1991, is an agricultural engineer, and widely known for his close links with the Muslim Brotherhood since the days of his youth. Hussein is one of the 28 people convicted in 2017 by an Egyptian court for the June 29, 2015 assassination of Prosecutor General Hisham Barakat.

Hussein, convicted in absentia, fled to Somalia via Sudan. His first plan was to fly to another friendly country, Malaysia, to seek refuge there. His friends suggested a flight to Kuala Lumpur via Istanbul. No, that ticket would be expensive. Someone else suggested a cheaper ticket ($860) to Cairo via Istanbul, but he did not take the Cairo flight. He did NOT want to go back to Egypt, but because he could not obtain a Turkish visa in Mogadishu, he wanted to pretend he was going to Cairo. He was, in fact, planning to stay in Istanbul with the help of his friends in the Ikhwan: his friends in Turkey might help him slip into Turkey illegally.

As an Egyptian citizen, he had to be younger than 18 or over 45 to qualify to apply for a Turkish e-visa. He failed to qualify. The Turkish embassy in Mogadishu did not have the authority to issue this Egyptian citizen a visa.

On the evening of January 16, 2019, Hussein arrived in Istanbul, with a ticket for a connecting flight to Cairo on the 17th — a trip he did not intend to take. At the Turkish immigration counter, he said he wanted to apply for an e-visa. Turkish authorities told him that due to his age, he is not entitled to apply for an e-visa. Helpless, Hussein tells Turkish authorities that he cannot take the flight to Cairo because an execution order is waiting for him there.

Turkish officials tell him they do not have any evidence of a court decision about him, execution or not, and no legal documents to prove that he was in danger of execution in his own country. So, the plan to smuggle Hussein into Turkey fails at the immigration desk. The Turkish passport police, unaware of the political troubles awaiting them, put him on a flight to Cairo on January 18. Upon his arrival, Egyptian authorities placed him under arrest.

By now, Hussein’s Egyptian and Turkish “brothers” are shocked and enraged, and launched a campaign to alert President Erdoğan and other government officials of the “grave mistake.”

The “mistake” was that the Erdoğan administration was not expecting Hussein, so the immigration officers treated him as just another illegal entry. He would not have been arrested and extradited if the Turkish authorities had known he was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Müfid Yüksel, an Islamist columnist in Turkey wrote: “Those [officials] who extradited him should be probed.” Another Turkish journalist, Adem Özköse, wrote: “Our brother Hussein has been extradited to the Sisi administration. Those who are responsible should be held to account”.

Kenan Alpay, from the militant Islamist daily Yeni Akit, appealed to Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu and Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu: “Why are you still silent [on the Hussein affair]?” This, said Rıdvan Kaya, head of an Islamist NGO, Özgür-Der, is providing a bloodthirsty dictator with new blood.

Is this a subtle step taken by the Erdoğan administration to offer an olive branch to his arch-enemy, el-Sisi of Egypt? Is Erdoğan changing course and abandoning his ideological love affair with the Muslim Brotherhood? Is Hussein’s extradition an initial sign of a Turkish plan to normalize ties with Egypt, after six years of explicit hostilities? Why did Erdoğan extradite a 28-year-old member of the Ikhwan to the el-Sisi’s Egypt, while knowing that he would likely be executed? Is this a signal that there is a major policy change in Ankara?

To reach any of those conclusions would be a bit naïve. There are a number of reasons to believe that Hussein was not extradited to Egypt as part of a Turkish policy re-calibration or of a decision slowly to distance itself from the Islamist cause.

First, Erdoğan seems too ideologically rigid to make fundamental policy moves away from political Islam — his whole reason for being.

Second, he is heading toward critical municipal elections on March 31 and therefore not in a position to offend his Islamist grassroots supporters. As in every pre-election period, this, for Erdoğan, is the time to bash Israel and tone up pro-Hamas, pro-Ikhwan rhetoric as strongly as possible.

Third, there is Qatar, Erdoğan’s staunchest regional ally and the patron of Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a Qatari-based nonagenarian cleric wanted in Egypt in connection to the violent protests that followed the ouster of Morsi.

In a 2016 speech, al-Qaradawi praised “Sultan Recep Tayyip Erdoğan” as a man “who defends the nation in the name of Islam and the Quran and the Sunnah, and Sharia, and he speaks of standing in front of the tyrant.” The man did not say which tyrant, but in the jihadist lexicon, “the tyrant” usually refers to “infidels”: Christians and Jews as well as secular Muslims.

Fourth, the way Hussein was deported to his home country looks very much like a typical Turkish bureaucratic mishap. He was probably not expected to arrive in Istanbul with the intention of staying. He would most probably have been given preferential treatment by the Turkish embassy in Mogadishu had his friends not thought they could smuggle him into Turkey without a visa. It is most likely that the Turkish immigration officers in Istanbul were confused over whether he was a member of their president’s favorite organization, the Muslim Brotherhood, or if he was an Islamic State jihadist. As Hussein did not have valid papers for entry, they most likely did not want to take the risk.

The Istanbul governor’s office denied that Hussein had requested asylum. A statement from the office said on February 4:

"According to Turkish law, the foreign individual was sent back to his country with inadmissible passenger (INAD) status ... There wasn't any notice by the individual to airport staff or police force about an international asylum request, there is no information whether he is on trial in Egypt or any other country."On February 5, apparently panicked by the political repercussions of what would normally be a simple deportation, the governor’s office released a new statement saying that eight police officers working for Turkey’s passport control office were suspended, pending an investigation. That confirms that Hussein was not “politically extradited to Egypt”.

Erdoğan has always argued that Muslim Brotherhood is not a terror organization, but rather an “ideological organization”. His “ideological” kinship with the Brotherhood remains in place. Early in January, DITIB, the Turkish government-backed Islamic organization operating in Germany, invited two Brotherhood members to its conference in Cologne. Henriette Reker, a spokesperson for Cologne’s mayor, said “there was no place for radicalism in Cologne”. The Cologne conference confirms that Turkey is still officially supporting the Muslim Brotherhood: a Turkish government agency invited two Brotherhood members to its event in the German city.

Erdoğan’s feud with Egypt’s El-Sisi runs deep. Erdoğan has a kind of emotional, ideological attachment to the Ikhwan which, after having deposed its president, Mohamed Morsi, el-Sisi views as an existential security threat to his country.

Starting in 2015, Turkey provided safe haven to Muslim Brotherhood members, including broadcasting their messages from Turkish territory.

Just last year, a celebration in Istanbul brought together like-minded Islamists, including former Hamas political bureau chief, Khaled Mashaal, to celebrate the Muslim Brotherhood’s 90th anniversary. At the same conference, Yasin Aktay — a professor and MP from Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party as well as a senior advisor to Erdoğan – said, rather inaccurately, “Ikhwan has never diverted from the path to peace … it has never resorted to violence”.

According to the Syrian journalist based In Turkey, Hüsnü Mahalli, “most influential Brotherhood members in the world reside in Turkey.” Mahalli says there are 2,000 Brotherhood media members in Turkey, 10 television stations and several radio stations. Altogether, Mahalli says, there are more than 5,000 Ikhwan members given refuge in Turkey thanks to Turkish and Qatari money.

False alarm. Erdoğan apparently has not changed, after all.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News