There was a firefight

During the winter of 2019, teams of U.S. Army Special Forces and U.S. Marines were positioned alongside their allied militia unit, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), by an oil field near Deir Ezzor, Syria. What looked like a Russian-led militia force, including a number of armored vehicles, lined up nearby in preparation for a ground attack. American military leaders activated a hotline to the Russian commander in Syria, who stated that the hostile forces were not Russian. Given that official confirmation, Secretary of Defense James Mattis instructed Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford to eliminate that force if it became necessary to defend U.S. forces and the SDF. On Feb. 7, 2019, the attack occurred and the American and SDF forces carried out that order.

During the engagement, the combined Russian and Syrian force deliberately advanced on a known and identified U.S. and SDF position. In the ensuing four-hour battle the U.S. and SDF applied a combination of close air support, artillery, and direct-fire weapons, killing more than 300 of the attackers. There were no U.S. casualties. Later reporting revealed that up to 30 of the dead were Russian soldiers ostensibly working for the Wagner Group, a quasi-official company owned by a Russian oligarch, Yevgeny Prigozhin.

In all likelihood, Wagner Group is a Kremlin condoned cover company and some of those Russians might have been active members of the Russian special forces known as Spetsnaz. While the Russian military had at first disowned the mixed Russian and Syrian force, toward the end of the battle they called the hotline and asked U.S. forces to cease their defensive kinetic strikes. Both the U.S. and Russian soldiers at Deir Ezzor were fighting at the tip of their respective national security spears and their respective national policies essentially pit the two directly against one another. What occurred at Deir Ezzor had serious potential for escalation and miscalculation. Similar situations in the future have the potential to trigger an all-out war between the United States and Russia.

This paper looks at the 2018 U.S. National Defense Strategy (NDS), and the Irregular Warfare Annex (IWA) to that guiding document, with recommendations on how to better implement the strategy. It also analyzes the current Russian way of conducting irregular warfare by reviewing their actions in Ukraine, Syria, and Libya.

The counter-terrorism hangover

In 2018, leaders at the Department of Defense (DoD) reviewed the almost 20 years of near continuous counter-terrorism operations and realized that maintaining a competitive advantage over near-peer adversaries, China and Russia, and dealing with rogue state actors, North Korea and Iran, needed to be a higher priority than counter-terrorism. Subsequently, Secretary Mattis and his staff drafted the NDS, publishing it on Jan. 19, 2018. This document placed China and Russia as the top two priorities, followed by the rogue states North Korea and Iran, with counter-terrorism falling to the fifth national security priority for the United States.

During those almost 20 years of counter-terrorism operations, the modern battlefield has become increasingly complex and multi-dimensional. The U.S. soldiers in Syria were conducting a counter-terrorism operation, yet they found themselves supporting the second-highest national defense objective of countering Russian aggression. The national defense priorities were playing out in Syria in real time. It was in Syria, not in eastern Europe or in the Arctic Ocean, where the so-called contact layer of competition emerged. If the United States is going to truly embrace the NDS, it should do so in places like Syria. Our forces are fully capable of executing the strategy in support of all the priorities, but they need the authority, the resources, and the policy guidance to do it effectively.

Get in the game

Sean McFate, a professor of strategy at the National Defense University and Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, said in The Return of Mercenaries, Non-State Conflict, and More Predictions for the Future of Warfare, “Conventional war thinking is killing us. From Syria to Acapulco, no one fights that way anymore. The old rules of war are defunct because warfare has changed, and the West has been left behind.”

The IWA of the 2018 NDS is an attempt to address that issue. It specifically directs DoD to apply the irregular warfare skills acquired in the last 20 years of executing counter-terrorism against near-peer competitors and rogue state actors. Since Sept. 11, 2001, the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) has been at the epicenter of U.S. counter-terrorism operations, and will likely be required to do the heavy lifting when it comes to the irregular warfare efforts against near-peer competitors and rogue states. The IWA also says conventional forces should play a prominent part in these efforts. Although not all-inclusive, irregular warfare includes counter-insurgency, foreign internal defense, partner force operations, information operations, unconventional warfare, and cyber operations.

In addition to U.S. military special operations, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) has developed and maintained a highly effective expeditionary irregular warfare capability. In order to mesh all of the capabilities within the U.S. arsenal, the IWA needs a companion national covert strategy that aligns presidential findings with the overall national defense objectives. This is the most effective way to have a clandestine and covert whole-of-government strategy. Once the strategic planning and guidance have meshed, the only requirement needed is the legal authorities to allow these organizations to compete, and the political fortitude to exercise those authorities.

Authorities needed: global and expanded, to match our priorities

On Sept. 14, 2001, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the military to apply “necessary and appropriate” force against those who “planned, authorized, committed or aided” the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. This authority, known as the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), has been interpreted by all subsequent administrations to include direct military action against al-Qaeda and all of its affiliates, including ISIS.

It was that authority that placed those U.S. forces on a counter-terrorist operation in Syria. However, the 2001 AUMF does not apply to near-peer competitors or rogue states, and it is unlikely that Congress would authorize the use of direct military action against them. In order to counter near-peer adversaries and rogue states, new authorities are required. These should not authorize direct military action (except self-defense), but they should authorize other actions that could be effectively applied. These authorities should be overt, clandestine, and covert to effectively counter Russia. There is currently a nascent effort in the U.S. House of Representatives to provide authority and funding for DoD to conduct partner force operations against Russia. This effort is under Section 1202 of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Unfortunately, this authority is confined to the U.S. European Command (EUCOM) theatre of operations and is not authorized in the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) theatre of operations, which includes the Middle East.

Although the European theater is important, countering Russian expansion should not be limited to the European continent. The four-hour battle at the Syrian oil field is a perfect illustration of why these AUMF-like authorities need global expansion and redefinition. The Russian forces were advancing to claim the natural resources of a war-torn Syria for the benefit of the Kremlin. The Russians do not have geographic restrictions on their partner force operations; neither should the United States. The U.S. has the capabilities to compete. Our authorities are not keeping pace with Russian expansion, and this has hampered our efforts to counter them as they gain influence in the Middle East.

The “Gerasimov Doctrine”

Not to be left out in the cold, Vladimir Putin saw the U.S. focus solely on counter-terrorism as an opportunity. The “Gerasimov Doctrine” was articulated in a speech in February 2013, when Valery Gerasimov, the chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia and first deputy defense minister, explained how Russians view Western encroachment, primarily through NATO alliances. According to many experts, including, most recently, Ben Connable of the RAND Corporation, Gerasimov’s articulation was an iteration of a time-tested Russian approach to conflict at a violence level below conventional war. Some also believe that Gerasimov was simply stating what he thought the United States was doing in irregular warfare and not describing a new Russian doctrine.

Regardless, in that speech, Gerasimov made clear hybrid warfare has always been a part of Russian strategy, and has recently been accelerated at Putin’s behest. Gerasimov specifically emphasized the use of propaganda and subversion. He focused on how a thriving state can be transformed into a “web of chaos” through foreign intervention. After the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2014, many looked back at Gerasimov’s speech and found a blueprint for Russia’s actions. The Russian intervention in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea is a clear demonstration of current Russian irregular warfare capabilities.

In Crimea, they did so quasi-covertly by using proxy forces and by masquerading their soldiers using private security companies like the Wagner Group. The Russians effectively combined clandestine military special operations forces (the “little green men”), disinformation operations, and social media manipulation. In all likelihood, they also covertly pushed for political support of their objectives using key local influencers. This manipulation of the political systems within other countries is done routinely by Russia, but not by the U.S. because of moral and ethical issues. In total, their use of overt and covert capabilities illustrates the Russian appetite for irregular warfare in their approach to modern warfare.

As highlighted by Crimea, the Ukrainians are fighting Russian aggression every day in their country — for themselves, for Europe, and for the rest of the West. The U.S. has a responsibility to support allies as they push back against Russian aggression and expansion. With a taste of success from Crimea, the Kremlin has expanded its irregular warfare efforts. Using the lessons learned, Russia has made substantial gains by increasing its influence and countering the U.S. in the Middle East, especially in Syria.

Russia in Syria

The Syrian civil war began in 2011 as part of the broader Arab Spring movement. The regime of Bashar al-Assad (much like that of his father Hafez) reacted to the uprising with brutal force. From the initial salvo against the protesters until today, the war has engulfed the region, caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, displaced millions more, and brought in global superpowers supporting opposite sides of the conflict.

Between 2012 and 2013, the U.S. began programs to support the insurgent forces attempting to overthrow the Assad regime. One program was successful but was canceled, which closed the door on any chance of the insurgent movement forcing the regime to a negotiated settlement. Regardless, in 2015 Russia became involved to prevent the collapse of the regime. Their support was two-fold. From the political side, Russia has been guiding Assad’s decisions. The U.S., in an effort to isolate the regime politically, has been forced to use Russia as the intermediator.

This has increased Russian influence in the conflict as the U.S. relies on them to accurately relay information without manipulating it for their own purposes. This approach supports the underpinning of Gerasimov’s speech as he highlights the use of propaganda and subversion. From the military side, Russia has provided tactical air support, special forces advisors, ammunition, logistical support, communications infrastructure, and other technical assistance. As a result of Russia’s intervention and support, the Assad regime has remained in power, even if it had to commit some of the most horrific war crimes in a generation to do so.

Russia’s actions led to substantial benefits for its military posture in the Middle East. This includes a strategic warm-water naval facility in the eastern Mediterranean, at Tartus, as well as air bases in and around the capital of Damascus. Russia successfully countered the U.S. and our policies of regime change and of ensuring that those who commit war crimes will be held accountable as called for in the UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2254. Through an unconventional approach, by supporting proxy forces, Russia has actually reduced its military budget by 20 percent while still making strategic geographic and political gains. A withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria will cement all the gains Russia has made, leaving them as the ultimate victor on the irregular warfare battlefield of Syria.

Not being blind to the changing landscape of Russian expansion in the Middle East, especially Syria, the bipartisan U.S. congressionally directed Syria Study Group Report was published in September 2019. It provides an excellent assessment of the situation and recommendations for the way ahead. The study specifically says that the U.S. underestimated Russia’s ability to use Syria as an arena for regional influence, and as a result, Moscow was able to prevent the Assad regime from being overthrown, and in the process, “reestablished itself as a crucial player in the region’s politics for the first time in decades.” Russia has blended a covert and overt approach to its activities in Syria and has been aggressively pursuing its objectives using irregular warfare. The U.S. has been using most of its assets and resources on counter-terrorism and has fallen behind in the competition against its higher priority adversary.

Libya is the next battleground

During the last months of 2019, Russia made substantial investments in Libya. As per open-source information, the military part of those investments consists of troop and material contributions, to include quasi-official troop contributions through the Wagner Group. From mid-October through November 2019, over 200 Wagner Group soldiers arrived in Libya, supporting Gen. Khalifa Hifter, a dual Libyan-American citizen who was appointed commander of the Libyan National Army (LNA) by the Libyan House of Representatives. Hifter is supported by Russia among other nations. They are against the Government of National Accord (GNA), recognized by the UN as the legitimate government, led by Chairman Fayez al-Sarraj.

The Wagner Group soldiers increased the lethality of Hifter’s military. One resource that Russia has employed very effectively with very limited costs is its snipers. It has also used the advisor skills acquired in Syria to make the LNA more capable in its engagements. In addition to providing soldiers with higher lethal skills, Russian Sukhoi jets, coordinated missile strikes, and precision-guided artillery are adding to Hifter’s overall campaign as well. Through a combined overt and covert effort, the Russians are tilting the conflict in Libya in their favor, and they are creating enough chaos to carbon-copy their expansion efforts beyond Syria.

Meanwhile, the U.S. appears to be locked in policy indecision. Our previous efforts within Libya centered on eradicating ISIS from the city of Surt. Those large-scale U.S. counter-terrorism efforts effectively concluded in 2017 with the defeat of ISIS-Libya. Since then the U.S. hasn’t played a large part in shaping the political outcome in Libya. Although still supportive of Sarraj, the U.S. has been hesitant to invest in another low-scale conflict on the African continent. According to one former U.S. partner, Muhammad Haddad, a GNA general, “We fought with you [the United States] together in Surt and now we are being targeted 10 times a day by Haftar.” Officially, the U.S. is a supporter of the UN-recognized GNA government, but we have sent mixed messages including congratulating Hifter for “killing the terrorists.” Unfortunately, some of the “terrorists” Hifter is targeting are the Libyans who fought ISIS as partners of the U.S. It is easy to see the fissures for Russia to capitalize on and exploit to gain further influence in the Middle East.

The U.S. has done little to counter Russia or Russian-backed forces in Libya, or throughout the continent of Africa. With the recently announced reduction of U.S. forces in Africa Command (AFRICOM), near-peer competitors will continue to outpace U.S. influence in key countries. Competition with Russia should not be tied to geography. It should be tied to where the Kremlin is trying to undermine U.S. influence. They have done this with relatively little investment through the use of partner force operations and other irregular warfare actions. The U.S. needs to do the same and meet Russia in these areas with authorities and resources to compete and prevent them from expanding their influence.

2020 vision: a clear-eyed approach

The U.S. should not simply replicate Russian actions, as many are unethical and immoral. The U.S. should not create chaos and destabilize regions so that we can then swoop in as the “solution to the problem” as the Russian do. We have our own way of conducting irregular warfare within our legal and ethical standards. This includes adherence to the law of armed conflict, the conventions of the UN, and under the oversight of the U.S. Congress in the armed service and the intelligence committees.

U.S. leaders need to recognize the nature of warfare has changed. Russia does not want an all-out conventional war, as it would be crippling for all nations involved, but they are actively conducting an irregular war against U.S. interests every day. Russia’s new style of warfare is going to look like Crimea, Syria, and Libya. In order to counter this, the U.S. must present a unified front and commitment to carrying out the NDS. This includes a comprehensive overt and covert national strategy, opening up the authorities for the military to do partner force operations, and having the political fortitude to take the actions necessary to compete. This political fortitude should also include vocalization of, and condemnation of, malign Russian activity within the international community.

The longer U.S. decision-makers in Washington D.C. stall, the more our national security goals will lag behind Russian expansion in the Middle East. The longer we stall in implementing the IWA, the more difficult it will be to catch up to the Kremlin and gain lost ground and influence in the Middle East. It might not be our preferred form of warfare, but it is the warfare we find ourselves in.

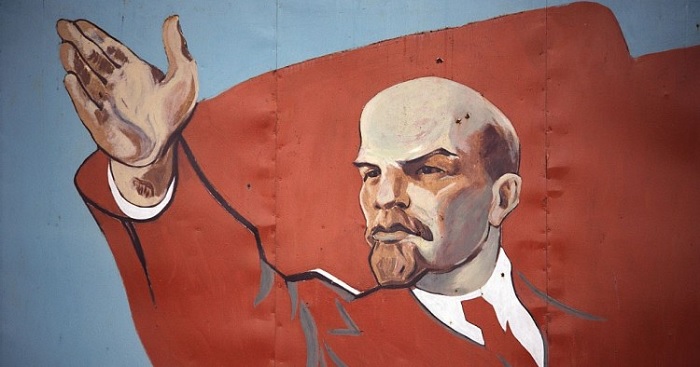

Vladimir Lenin said, “You probe with bayonets. If you find mush, you proceed. If you find steel, you withdraw.” The U.S. needs to be steel.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News