Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan didn’t give a damn about possible European Union sanctions against Turkey, and the EU has proved him right.

No need to indulge in semantics and take pains to conceal the fact: Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan defied the European Union — and he won.

Before the European Council summit Dec. 10-11, European Council President Charles Michel had accused Turkey of playing a cat-and-mouse game that has to stop. Erdogan retorted to the EU on the eve of the ostensibly fateful summit in a belligerent tone, saying he was not concerned about possible European sanctions as they would have no impact on Turkey. Yet he also emphasized that Turkey’s strategic objective to become an EU member state remains unchanged, thereby creating false hopes and optimism.

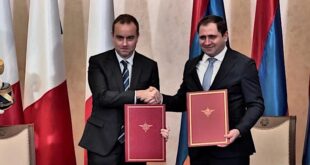

When the EU leaders met in Brussels haggling over the wording of the continuously changing drafts of the European Council’s statement on Turkey on Dec. 10, Erdogan was in Azerbaijan as the proud leader who enabled the Azeri victory over Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh war in the South Caucasus.

The EU summit’s outcome has indicated that the Turkish pundits, as well as many other non-Turkish analysts, who are critical of Erdogan with legitimate reasons, have a strong tendency of wishful thinking to see the Turkish president as the loser in his assertive foreign policy moves. The Erdogan critics were expecting tougher sanctions in accordance with the consistent calls by EU member states — France, Greece and Cyprus.

Yet, after some bickering among the member states, the summit’s conclusion text vis-a-vis Turkey fell considerably short of what these three countries wished to see. The EU has opted out of limited sanctions against Turkey for unilateral moves in the eastern Mediterranean, slightly expanding previously approved sanctions against individuals and institutions involved in Turkey’s hydrocarbon exploration activities in the contested waters of the eastern Mediterranean.

The previous sanctions list that was drawn up during the bloc’s October summit was already very limited and largely symbolic, and the long-awaited outcome of the recent meeting did not go beyond that.

Former Turkey rapporteur of the European Parliament Kati Piri shared her disappointment in a tweet: “[Seven] paragraphs on Turkey, not a single word on human rights & rule of law situation in the country.”

Reuters reported succinctly what is decided in Brussels: “Shying away from a threat made in October to consider wider economic measures, EU leaders agreed a summit statement that paves the way to punish individuals accused of planning or taking part in what the bloc says is unauthorised drilling off Cyprus. The steps did not go far enough for Greece, with envoys saying the country expressed frustration that the EU was hesitant to target Turkey’s economy over the hydrocarbons dispute.”

The respected Greek daily Kathimerini conceded that the summit was a diplomatic loss for Greece, naming a number of EU member countries that pushed for a text to the liking of Erdogan. The final text, the report said, “is significantly far from the solid answer that Athens wanted.”

“Until late yesterday, the well-known Berlin-Rome-Madrid bloc insisted on postponing serious decisions — with Italians particularly negative about the prospect of new sanctions against Ankara. The position of Greece and Cyprus was weakened by the apparent reluctance of France to insist on more substantial measures, while Austria also seemed to rest with the lukewarm wording of the original drafts.”

The Europeans apparently wanted to deal with Turkey under Joe Biden’s presidency, as they hope to cooperate and coordinate with the United States in regard to Turkey.

The EU is obviously aware of the fact that its influence in Ankara has diminished. The main European powers are clearly divided between France that denounces Erdogan’s policies and Germany that mostly seeks to appease Turkey. Germany has important arms deals with Turkey, in addition to its willingness to assuage Ankara for complying with a refugee deal that German Chancellor Angela Merkel brokered in 2016.

Regardless of these reasons, the arguably mild reaction of the EU to Turkey’s “belligerency in the eastern Mediterranean” and “provocations,” presented a lifeline to Erdogan that would comfort him until the next European Council summit in March 2021.

The Turkish president seems quite confident that March 2021 would not be much different than December 2020 in regard to Turkey-EU relations. Speaking to reporters after the Friday prayer Dec. 11, he praised those “reasonable countries” in the EU that prevented the Greek and French efforts. “The next meeting of EU leaders in March would not yield results [that would hurt Turkey],” he added in a self-assured manner.

His self-confidence in dealing with the Europeans emanates mostly from his experience with the EU and the many European leaders he knew over the years.

Former US envoy to Syria James Jeffrey highlighted in a blunt manner that Erdogan knows how to push the limits. In his interview with Al-Monitor, widely circulated in Turkish online media outlets, Jeffrey described Erdogan as “a great power thinker. Where he sees vacuums, he moves.”

“Erdogan will not back down until you show him teeth. That’s what we did when we negotiated the cease-fire in October of 2019. We were ready to crush the economy,” Jeffrey said “That’s what Putin did after the Russian plane was shot down. You have to be willing, when Erdogan goes too far, to really clamp down on him and to make sure he understands this in advance.”

Erdogan is pretty sure that the EU is too disunited to show him its teeth despite the willingness of some of its members. He also knows that he can depend on those “reasonable” EU member countries having lucrative deals with Turkey.

The EU, without any doubt, could have inflicted severe damage on Turkey economically at a time when the coronavirus outbreak in Turkey is escalating and the country’s crisis-hit economy is already ailing. However, the Europeans also fear an ultimate collapse of Turkey’s economy that would unleash all the social, economic and political demons over Europe.

Thus, the weakest element of Erdogan’s reign — aka the country’s ailing economy — paradoxically provides political strength to him in his dealings with Europe. That’s why he can afford to be belligerent with the EU, and he can win against his European opponents.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News