As Erdogan teeters between the West and the Russia-China axis, it will be his goal of securing his political future at home that determines which direction he takes.

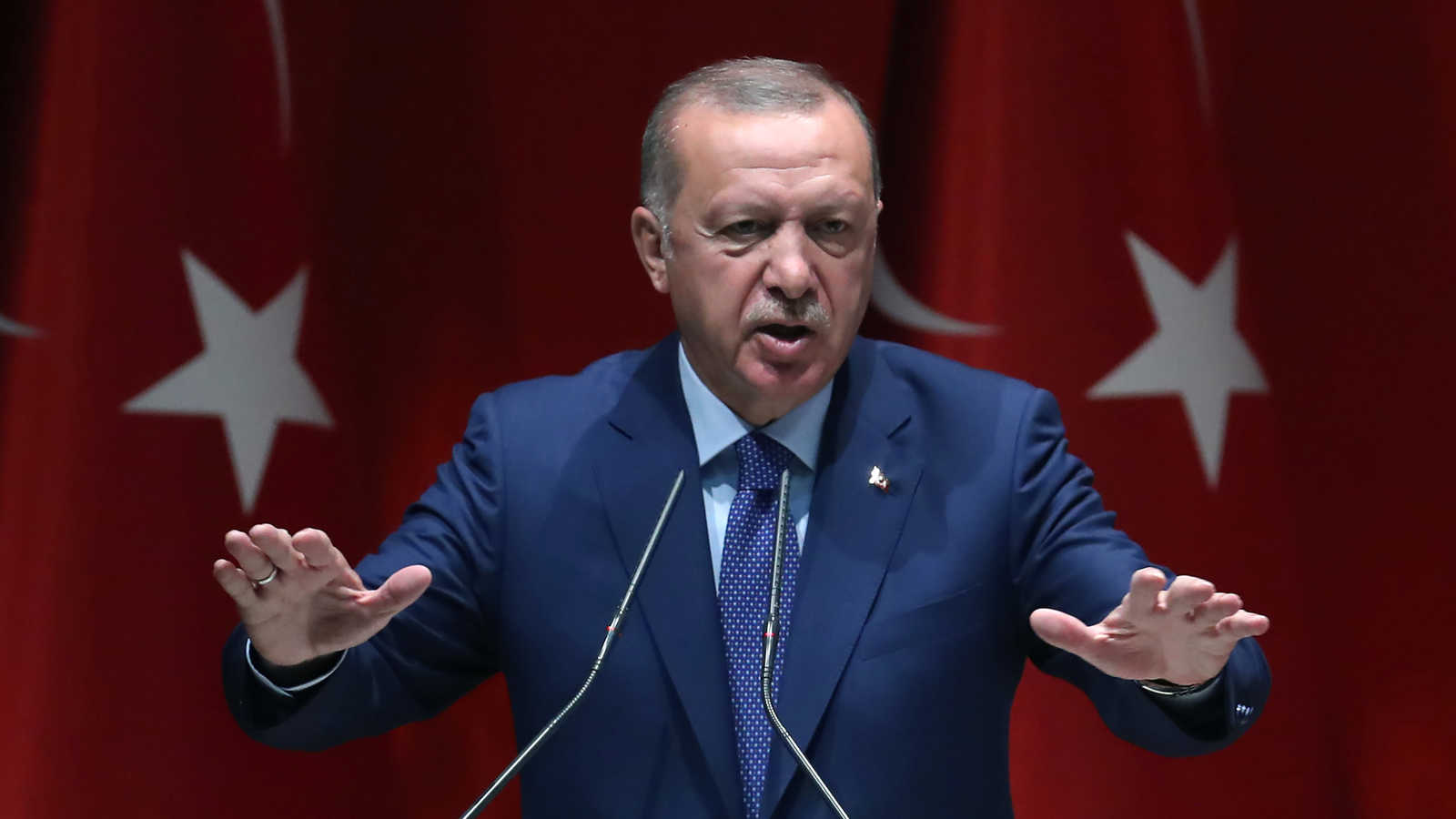

In a span of five days last week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan delivered two diametrically opposed messages to Washington, highlighting his vacillations on ties with the United States and, more generally, with the West — a balancing act that he can no longer sustain.

In a Feb. 15 speech following the deaths of 13 Turkish captives at the hands of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a designated terrorist group, Erdogan fired a broadside at Washington for “siding with terrorists,” incensed with a US condemnation of the executions that seemed to take Turkey’s version of the events with a grain of salt. Referring to the PKK and its Syrian affiliates, Erdogan said, “You claim to not side with terrorists, to not side with the PKK, the YPG and the PYD, but you are clearly siding with and standing behind them.” He charged that the United States had “delivered thousands of truckloads of ammunition to terrorists” in northern Iraq.

Then, in a video address to the American Turkish community Feb. 20, Erdogan upheld the “strategic cooperation” between the two countries. “We believe that our common interests with America outweigh our disagreements by far. We are willing to further strengthen our cooperation with the new American administration, based on a long-term perspective and a win-win approach,” he said.

Such dizzying turnabouts have less to do with Turkish-US ties and more with Turkey’s domestic politics and Erdogan’s indecision.

To start with, it is worth noting that one can no longer speak of a Turkish foreign policy as we knew it. Since Turkey’s 2018 transition to an executive presidency system tailor made for Erdogan, what Ankara has pursued is hardly a national foreign policy, but rather foreign relations designed to protect and strengthen Erdogan’s political standing at home, very much in the style of public relations. To better understand Erdogan’s contradictions, one needs to view Ankara’s diplomatic choices not as foreign policy but calculations to ensure Erdogan’s political survival or publicity stunts to boost his image at home.

Ankara’s strategy to play the United States and Russia against one another in crisis regions such as Syria, Iraq, Libya, the eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea basin and Nagorno-Karabakh, taking advantage of grey areas in US-Russian ties, has come to an end as a result of more assertive moves by the United States, Russia and Europe and, most critically, the change of guard in Washington. The Joe Biden administration and the Kremlin are both signaling that the time has come for Erdogan to choose his side.

Yet Ankara seems confused on whether it should make a decisive turn toward the United States and Europe, Turkey’s traditional allies, or opt for closer partnerships with Russia and China, as the country’s vocal Euroasianists preach. In a rift that has grown increasingly visible since last year, Erdogan’s supporters are split on which direction would better serve his interests at home.

In February 2020, for instance, Burhanettin Duran — head of the pro-government think tank SETA and a member of a foreign policy board advising the president — wrote that the United States should become more active in Syria’s rebel-held province of Idlib to curb Russia. The article, penned amid Turkish-Russian tensions in Idlib at the time, prompted harsh response by the daily Aydinlik, the mouthpiece of Turkey’s Euroasianists, who have ardently backed Ankara’s rapprochement with Moscow.

And after Biden’s victory in the US elections, Duran wrote that “new geopolitical equilibriums” were forcing Ankara and Washington to cooperate, urging the two sides to “turn over a fresh leaf.” Evidently, Duran and a number of other foreign policy experts close to Erdogan believe that leaning to the United States and Europe and keeping transactional ties with the West will best serve Erdogan’s domestic agenda. In a reflection of this thinking, Ankara seems to be trying to leverage the crisis with Washington over its purchase of the Russian S-400 air defense systems to extract concessions that would play into its hand at home. From Ankara’s perspective, a good give-and-take would see it give up on the S-400s in return for a free hand to pursue the PKK in Iraq and Syria. Such military operations promise the biggest gains in domestic politics.

The option of leaning to the United States and Europe, however, is a nonstarter with the government’s de facto ally, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which has trapped Erdogan into a nationalist and isolationist discourse as well as Euroasianist and anti-Western cliques.

In intriguing timing in early February, Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu — a figure close to the MHP who has become the cheerleader of Turkey’s nationalists in recent years — accused Washington of being the real culprit behind the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, just as presidential aides were scrambling to arrange a phone call between Erdogan and Biden. Soylu’s abrupt outburst apparently sabotaged the effort, with Washington denouncing the allegations as “unfounded and irresponsible claims … inconsistent with Turkey’s status as a NATO ally and strategic partner of the United States.”

Given Erdogan’s ample record of pragmatic U-turns, many observers expect he will ultimately opt for fence-mending with the United States and Europe, though with a view of pursuing businesslike, transactional ties rather than a committed alliance. Skeptics, on the other hand, believe he has reached a point of no return in an anti-Western Euroasianist shift that is also authoritarian and isolationist.

This author, however, believes that Erdogan is still undecided, struggling to accept that 2021 will be his moment of truth; hence his frequent vacillations, which exact a price on the whole nation as Turkey’s international credibility and predictability suffer.

Some idea of Erdogan’s intentions is likely to emerge soon. His Justice and Development Party (AKP) will hold a grand convention March 24 to elect its leaders for the next three years. The new leadership will shape AKP policies ahead of presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for 2023. Erdogan is also reportedly planning to replace some ministers and party leaders in the run-up to the convention. All those changes will offer ample clues about which direction Erdogan is taking.

Turkey watchers will remember the international media debates several years ago on whether Turkey’s axis was shifting under Erdogan. Fasten your seatbelts, we’ll know the answer this year.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News