Every March,[1] nearly 5,000 delegates descend on Beijing for the meeting of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political and Consultative Conference (CPPCC), generally simply referred to as the lianghui, or two meetings. The NPC, with nearly 3,000 members representing the country’s provinces and municipalities, is the world’s largest legislature, which is perhaps appropriate for the world’s most populous country.

Despite its large size, the NPC it has very little power. Important decisions are made at the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which typically meets in the fall, and then rubber-stamped at the NPC. The CPPCC, with about 2,200 members, is strictly an advisory body that is often imperfectly compared to Britain’s House of Lords. Its composition is more broadly representative of Chinese society as a whole and includes retired party elders, academics, businesspeople, and luminaries of the sports and entertainment worlds. Both meetings are highly scripted affairs meant to showcase the government’s achievements of the past year and introduce plans for the future. As such, they are eagerly awaited by China analysts over the world for clues as to what to expect.

Clear Skies and a Bright Future

The highlight of the NPC was, as always, the Government Work Report, delivered by Premier Li Keqiang. It brimmed with self-confidence for a number of reasons. First, the economy had rebounded from a historic pandemic-induced contraction in the early months of 2020 to finish the year at a 2.3% growth rate, with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) the only major economy to expand at all that year.[2] In a related second development, General Secretary Xi Jinping was credited with having conquered the coronavirus. Third, in December, the PRC’s Chang’e 5 mission successfully delivered samples of lunar rock and dust to Earth, with Tianwen-1, China’s first interplanetary mission now in Mars orbit and scheduled to touch down later this year. At the end of February, Xi received credit for eliminating extreme poverty, a full decade ahead of the 2030 target set by the World Bank for doing so.

The cult of Xi, its antecedents noticeable as early as 2012 when he first came to power, was in full bloom, with an effusive report by the official Renmin Ribao declaring that “General Secretary Xi Jinping has stood at the strategic height of building a well-off society in an all-around way and realizing the Chinese dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Analysts speculated that the motive behind this hyperbole might be to reinforce the wisdom of allowing Xi to remain as president beyond the customary two five-year terms, as a controversial 2018 change to the constitution has already legitimized his right to do.

Certainly, the future looks promising. According to the Work Report, the target growth rate for 2021 is six percent, which actually seems excessively modest. Since six percent had been the target for pre-pandemic 2020 and the 2021 figure will take off from 2.3%, an 8% increase is more likely. The reported defense budget (most estimates believe the true figure is at least 40% higher) will increase by 6.8%, up from 6.6%, to $209 billion and already the world’s second largest. This year will mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, sure to be celebrated with all the pomp and parades befitting the PRC’s rise to superpower status. It will also mark the beginning of the country’s 14th Five Year Plan. Beijing will host the Winter Olympics in 2022.

For the coming year, the budget envisions major increases in research and development to close the supply gap in innovation with emphasis on quantum computing, 5G communications, and the development of electric vehicles. Eleven million jobs are to be created. A dual circulation system is being implemented in which domestic and overseas markets reinforce each other; the government has affirmed its commitment to global trade and investment. Longer-term goals, which outsiders consider difficult but not completely impossible, include doubling the size of the economy by 2035, becoming a “great modern socialist country by 2049” (however one chooses to measure that) and carbon neutral by 2060.

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

In a complete surprise, the 100th anniversary of the birth of Hua Guofeng, Mao Zedong’s alleged hand-picked successor, was commemorated. Hua was eased out of power by Deng Xiaoping only a few years after his ascension and disappeared from the political scene. As if to underscore the importance of the commemoration, on the night of the symposium, the popular television program Ping Yu Jin Ren, a series that began in 2018 with the apparent aim of touting Xi’s image as a great leader, prominently displayed on its screen two characters for loyalty, symbolizing Hua’s loyalty to Mao.

Speculation about what this meant was rife, especially when, although two unspecified members of the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee and three of the Politburo’s 25 members attended, Xi Jinping did not. Some observers opined that it was a symbolic rebellion against Deng for dismantling the cult of Mao, and hence affirming the cult of personality and Hua’s status as a loyal follower. One might also hypothesize, however, that, given Hua’s unceremonious removal from power, the commemoration was a warning to Xi Jinping loyalists about the costs of such fealty.

Was the increase in the tempo of praise for Xi simply, as it appeared to be, a sign of confidence the citizenry has in him, or a sign of insecurity? The cult of Xi has had its critics in the past; though currently silent in the present climate of restriction, they have surely not disappeared. No knives or sharp-edged instruments could be sold during the period of the two meetings. While hardly a sign of the leadership’s confidence in the people, such restrictions have happened before. Still, there are other indications that there were misgivings behind the façade of what one Japanese pundit called “predetermined harmony.”

Skepticism abounds on the war on poverty: China defines extreme rural poverty as an annual per capita income of less than 4,000 yuan ($620), or about $1.69 per day, while the World Bank’s figure is $1.90. The government has already acknowledged that those pulled out of poverty may sink back into it again. Fear of the collapse of the economic bubble remains: just as the lianghui were convening, Guo Shuqing, the country’s highly respected chief banking regulator, warned of rising risks from asset bubbles in global financial markets that he said were out of sync with real-world economic conditions. Guo’s primary worry, however, concerned the danger of a steep drop in home prices that could threaten the financial and economic stability of banks, since they would not be able to collect on mortgages. Inequality of income remains a serious problem, and the state pension fund is expected to run dry by 2035.

The government has promised reform of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), huge but often inefficient behemoths that have a drag effect on the state budget. Since they employ hundreds of thousands of people, dismantlement is unthinkable. Although restructuring has been tried in the past, it has achieved only modest results. Private entrepreneurs are reluctant to invest in SOEs since doing so would put their funds under state control. China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is officially 280%, though other estimates place it as 317-335%, and local government debt continues to be a problem.

In order to meet the target of doubling the economy by 2035, China would have to grow a bit over 4.7% annually for the next 15 years, which, considering recent past growth rates of over 6%, seems feasible. However, Michael Pettis, a professor of finance at Beijing University, points out that this does not take into consideration economic and demographic factors. If gross domestic product is to double by 2035, China’s debt burden will have to rise to over 400%, a level unprecedented in history. Pettis notes that “everywhere else, growth collapsed long before debts reached levels close to this.” In addition, because declining birth rates mean fewer workers, productivity will have to increase by unrealistic amounts.

What About Foreign Countries?

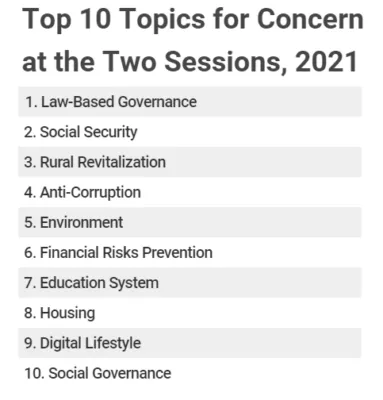

Although the challenge to U.S. primacy is implicit in the Work Report’s ambitious targets, most of it dealt with domestic matters. This fits well with the concerns of the average Chinese: An online opinion poll of 5.2 million people conducted by Renmin Ribao on their concerns for the two meetings listed no items relevant to foreign policy.

While we do not know how the poll was structured—perhaps people were responding to a limited range of choices—foreign affairs were clearly much on the minds of the leadership. At a press conference during the NPC, Foreign Minister Wang Yi warned the Biden administration to reverse the “dangerous practice” of support for Taiwan, calling it an insurmountable red line with no room for compromise. In a tone that resembled a lecture to a naughty schoolchild, Wang said that meddling in the internal affairs of other countries in the name of democracy and human rights would not be tolerated: “It is important that the U.S. recognizes this as soon as possible. Otherwise, the world will remain far from tranquil.” Differences of opinion on these and other outstanding issues between China and the United States, such as trade and intellectual property rights, are unlikely to be resolved when Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan meet with Wang and State Councillor Yang Jiechi, a former foreign minister likewise renowned for his intransigence, in Anchorage next week.

Wang also defended new legislation that would ensure only candidates loyal to Beijing could be elected to positions in Hong Kong as necessary to its security and rejected foreign governments’ charges that the party’s policies in Xinjiang amounted to genocide.

Despite many references in state media to the West declining while China continues its rise to power, Xi Jinping explicitly named the United States as the biggest threat to Chinese development. Indeed, the U.S. remains the world’s largest economy as well as one whose recent impressive scientific achievements have included a successful landing on Mars a few months before China’s mission is scheduled to touch down. But other countries also present impediments to Chinese progress. Moves to consolidate its claims to contested areas of the South and East China Seas have been met with resistance and nascent attempts to counterbalance by entities such as the Quad (Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S.) and the intelligence-sharing Five Eyes (Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, and the U.S.).

Assertive “wolf warrior diplomacy” has antagonized other countries as well. Among other examples, Guo Congyou, China’s ambassador to Sweden, has been summoned to the country’s foreign ministry more than 40 times in two years for his most undiplomatic criticisms of perceived slights to the country. Guo’s statement, “We treat our friends with fine wine, but for our enemies we have shotguns,” drew international attention. And, after Canberra refused to back down on calling for an independent investigation for the coronavirus pandemic that began in Wuhan, a Chinese newspaper editor compared Australia to “a bit like chewing gum stuck on the sole of China’s shoes. Sometimes you have to find a stone to rub it off.” This was followed by sanctions on major Australian exports to China, including coal, barley, and wine. China’s relations with several Southeast Asian states have been strained after Beijing unexpectedly cut the flow of the Mekong nearly in half, affecting water levels in Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.

Whether these irritations will rise to the level of genuine resistance remains to be seen. Most of these countries rely on trade with China to a greater or lesser degree and are aware that, as Australia discovered, retaliation will be swift. Chinese state media have been openly derisive of organizations such as the Quad, arguing that the interests of the individual countries involved will impede any meaningful degree of cooperation against China. Most or all of the countries involved may decide that wounded pride is less important than sacrificing economic gains, and will not seek to impede China’s ability to achieve the ambitious economic goals that it has set. The possibility of an economic downturn in China cannot be counted out, nor can that of an unexpected catastrophic event on the level of a pandemic. For now, however, China seems well-positioned to achieve the ambitious goals announced at the lianghui, and Washington should be prepared for that eventuality.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News