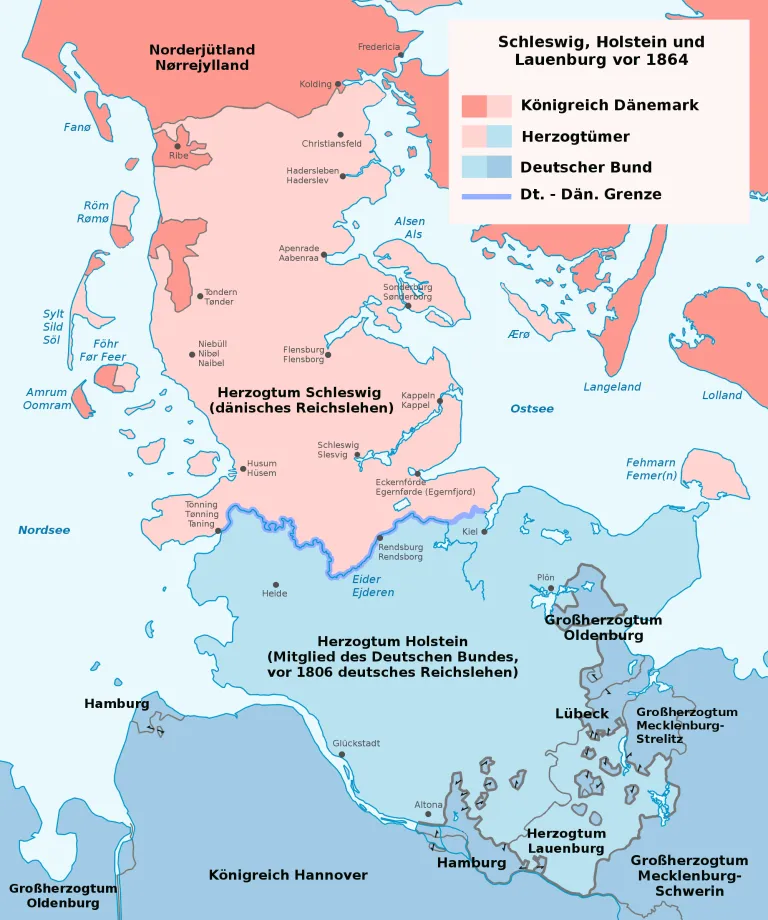

The Schleswig-Holstein Question was a notoriously problematic territorial dispute in the nineteenth century. It involved two groups of people, each with ethnic associations with neighbours (Denmark and Germany), living in adjacent pieces of land – Schleswig (Danish) and Holstein (German). For complex historical reasons, The Duchies of Schleswig-Holstein were treated as a separate state from either Denmark or Germany. This state had its own government; but the people of Schleswig and the people of Holstein had different ideas about how their government would change or its constitution would evolve.

Every time such a change occurred, it caused a war. That was because any change (whether enacting a new constitution or a change of Duke in accordance with competing hereditary principles applicable in each part of the territory) would be perceived as either pro-Danish or as pro-German; and the other side would declare war with a view to restoring the status quo ante. The British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston observed: “Only three people have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business – the Prince Consort, who is dead – a German Professor, who has gone mad – and I, who have forgotten all about it.”

Bosnia’s war ended in 1995, and in 2021 – some twenty-five years later – it is tempting to adapt Lord Palmerston’s sentiments to the situation in Bosnia. Bosnia’s war ended in partition; the territory that was once a province of federal Yugoslavia was declared an independent state albeit with layers of complex federal structures so that the country’s three groups of people, Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Serbs, who had segregated themselves from one-another into mono-ethnic geographical units during the war, could each effectively govern themselves. A formal, flimsy state-wide government structure was created for a very limited number of federal functions, such as central banking and foreign policy.

The details of so enormously a complex multi-layered federal structure for a small country were set out in a series of voluminous legal documents drafted by US State Department lawyers in late 1995, as the US Government mediated a settlement between the warring parties in Wright-Patterson Airforce Base in Dayton, Ohio. The principal mediator was the ruthlessly determined US diplomat Richard Holbrooke, and the legal drafting was undertaken by a team managed by his personal friend, Roberts Owen, US State Department Legal Advisor under President Jimmy Carter (1977-1981). Holbrooke and Owen did extraordinary work in mediating a resolution of Bosnia’s protracted and bloody three and a half-year war (1992-1995) in a mere three weeks. May they both rest in peace, and we should be grateful for their extraordinary work.

Nevertheless, as is always the case with law, we learn a lot with time. By contemporary standards the documents negotiated at Dayton appear antiquated. The language they use is not that of legal drafting in the third decade of the twenty-first century. In some parts the Dayton Peace Accords now seem naive. Substantial parts of the peace agreement were never implemented. One of the annexes to the peace agreement was a national constitution, which contained a number of mistakes or irreconcilable problems. The wartime circumstances in which the drafting was undertaken excuse the drafters; there was no time for sensible debate. Nevertheless the latent problems in the Dayton documentation, including in the Bosnian constitution, came to be noticed later on.

The constitution adopted so-called consociational principles, consociationalism being a concept first described by the political scientist Arend Lijphart in the 1960’s. Certain rights to elected office were distributed between “constituent peoples”. Hence the three-member Presidency described in the constitution must include one Bosniak, one Croat and one Serb; one of the legislatures, the House of Peoples, is likewise to be composed of equal numbers of each such group. The Judges of the Constitutional Court are also defined by reference to their ethnicity. The theory underlying consociationalism was to create political bodies that required the consensus of representatives from potentially competing ethnic groups in order to enact key political decisions. This, so the theory went, would encourage compromise, because any one of the groups could only get their political agenda enacted if they had the agreement of the others. Therefore in Bosnia there must be tripartisanship in everything that is done, and the parties would undertake quid pro quo agreements with one-another to achieve this.

Notwithstanding the optimism of 1960’s political scientists, in practice consociationalism turns out to be ineffective, for reasons parallel to those explaining why bipartisanship has become regrettably ineffective in the US Senate. In the Bosnian system the people who are are elected to institutions pursuant to their race, religion or ethnicity being identical with that of their voters have an incentive to adopt extreme positions related to their ethnic qualifying criteria, against the interests of other groups. In other words, consociationalism pitches different groups against one-another: this policy is good for Serbs and bad for our opponents the Croats / the Bosniaks, for example. Politics becomes binary under such a system: each elected representative has an incentive to push for policies that are good for us and bad for them.

If a representative elected in such a system does not adopt extreme positions, they will lose elections and they will be replaced by other representatives who do adopt extreme positions. That is because the “good for us, bad for them” narrative is enticing for voting populations; we all like to feel part of a group, and if an electoral system reflects this inclination then the result will be that ever more extreme representatives are elected and that there is ever less political space for moderates. As politics becomes more polarised, elected politicians who will undertake quid quo pro deals with their opposing number become increasingly rare. Consociationalism, although once sounding like a good idea, turns out to represent the most extreme form of democratic politics imaginable because it defines each political group in “us versus them” electoral terms. Approximately the same thing is happening in the US Senate right now, as the Republicans and Democrats have increasingly come to identify themselves not with policies but with groups of people. Bipartisanship has become extremely difficult as a result,

This is not an essay about US federal politics. The problems the US Senate is now having are but a trifle compared to the problems mixed up in the contemporary Bosnian Constitution. To give one example that has created particular controversy for some time, the current Croat member of the Presidency is not voted for by many Croats. It is estimated that 95% of his voters are Bosniaks, because he is an exceptional non-Bosniak member of a predominantly Bosniak political party in a consociational system. Therefore, both Serbs and Croats say, in a tripartite Presidency there are two Bosniak members, one Serb member and no Croat member. The two “Bosniaks” can outvote the Serb, and therefore both Croat and Serb confidence in the tripartite model of the Presidency is undermined.

The tragedy of the individual in question, Željko Komšić, is particularly acute because although in all likelihood he genuinely wants to govern on behalf of all three of Bosnia’s ethnic groups, he is eligible for election only because he is a Croat (the constitution says one member of the Presidency must be Croat); and yet he is elected by his electors only as a Bosniak (because Croats form a small minority of the Bosnian population). Mr. Komšić is therefore condemned every way he turns.

Although the Dayton drafters did not notice it at the time, the consociational system of government Bosnia is also racist. It forces people to identify themselves with one of three ethnic groups, something they may not be comfortable with because some citizens may not feel associated with any ethnic group and/or may be members of families with inter-ethnic marriages. Cititzens’ voting rights depend upon which ethnicity they have identified themselves with, when they may not have wanted to identify themselves with any of the three groups. This racism expresses itself most blatantly when we consider that some people in contemporary Bosnia are none of Bosniaks, Croats or Serbs. Those people, including Jews and Roma, are constitutionally disenfranchised from office; you cannot become a member of Bosnia’s tripartite Presidency unless you are a Bosniak, a Croat or a Serb. The same is true of the House of the Peoples, the upper house of federal legislature. The constitution says this explicitly. Hence there are some people in a country that imagines itself as a democracy, who cannot vote for certain candidate for electoral office, nor can they be elected to those electoral offices. This is racism against minorities, and it is something the European Court of Human Rights observed in a ground-breaking judgment some twelve years ago.

Nevertheless nobody has done anything about these things, irrespective of the judicial and other condemnation of the racism and discrimination built into the Bosnian constitution at Dayton. The reason why nothing has changed is because of what one international official with oversight over the country, High Representative Paddy Ashdown (2002-2006), called the “impossibly sclerotic” nature of Bosnia’s politics. It is very difficult to change the constitution – this is the sclerosis – in substantial part because it was imposed upon the three warring groups by the US government down the barrel of a gun. The Americans locked the various political antagonists in Wright-Patterson Airforce Base until they agreed to the constitution that had been drafted and proposed to them. Therefore there was never much domestic political buy-in to the Bosnian constitution from the beginning.

The second, more fundamental, reason why consociational systems are incapable of self-reformation from within is that constitutional amendment in a consociational system requires the moderate political bipartisanship (in effect, representatives of all three ethnic groups must agree) that consociationalism marginalises. This is something the architects of consociational models of government did not spot; but it came to light in Bosnia and Herzegovina and elsewhere, including the Duchies of Schleswig-Holstein, when consociationalism was put into action. Because they cannot amend themselves, consociational systems require constant external tutelage and supervision to prevent them from becoming embroiled in inertia (what Ashdown called their sclerosis).

The only way politicians, consociationally elected, can work together is if a foreigner, overlord, monarch or supervisor instructs them or guides them to do so. If there is such a person within the system – a fourth branch of government, if you like – then consociationally elected politicians can disclaim them politically, telling their electorates that the compromises necessary for government are not their fault but have been imposed by the overlord. This is the reason why Bosnia has had an international overlord for 25 years, the longest period of post-war international supervision of a territory in recent history. As a complex and radically consociational system of government, it needs such a fourth branch of government in order to keep operating.

The other notable European country with a dysfunctional consociational system of government is Belgium. Their system does not work terribly well either, and lurches from one threatened disintegration to the next after each election, as the Flemish people threaten to split from the French and German people unless they are granted more political and fiscal autonomy. Belgium’s High Representative is her King, Philippe / Filip, who is of mixed ethnicity and serves as an inter-ethnic mediator to negotiate the formation of Belgian federal governments after elections. His role becomes ever more taxing as the wealth gap between Flanders (Dutch-speaking Belgium) and Wallonia (French-speaking Belgium) becomes wider. The notion of Belgium’s survival as a federal state without its King might be regarded as about as unrealistic as the notion of Bosnia and Herzegovina in its current form surviving without its High Representative.

Hence we already have a provisional answer to the question posed in the title of this essay, namely how does the international community exit Bosnia in the sense of closing the Office of the High Representative. The very short answer is that under the current system of Bosnian government this cannot be done, because the High Representative and his staff are an essential fourth branch of government the presence of which is essential for Bosnia’s federal system to survive.

+++

Long-term Bosnia-watchers will observe that the High Representative, like the King of Belgium, rarely if ever needs to do much as this governmental fourth pillar. The latest High Representative, the Austrian-Slovene diplomat Valentin Inzko, is illustrative of that. He has been in office for some 12 years. He is able in principle to exercise unilateral executive and legislative dictates. To understand how the High Representative acquired this authority, the reader may wish to review this author’s 2007 essay “The Demise of the Dayton Protectorate”; little has changed in the last 14 years. Nevertheless Mr Inzko has issued little in the way of formal decrees. He has governed from a political distance, occasionally issuing approvals of disapprovals of policies or politicians, and talking to the parties, making threats and promises in private that are seldom carried out, in order to make sure that the Bosnian federal government works approximately in accordance with its mandate. Now in 2021 Inzko wants to retire, and suddenly we have a crisis of whether there should be such an official anymore whose mandate is to keep a country together that otherwise cannot properly be governed by the political extremists its constitutional structure inevitably creates.

One advantage Belgium has over Bosnia is that the Belgian Monarchy has a statutory line of succession from one King to the next, useful for retirement and replacement of individual office-holders; whereas with each retirement of a Bosnian High Representative the international community is left scratching its head as to whether there should be such an official anymore and if so then who it should be. Nevertheless the most important thing about a Monarch or High Representative is not necessarily who it is or whether they are good at their jobs (although obviously it is better that High Representatives are competent, Bosnia has not always been lucky), as much as there needs to be certainty as to who the next one will be and indeed that there will be a next one. This is a profound weakness in the system of the Office of the High Representative. The absence of clear answers to these questions each time a High Representative steps down, in 2021 as in multiple prior cases, creates political instability if not chaos because it is obvious that the country is at risk of melting down in one or other ugly way if no successor is promptly named.

The other difference between Belgium and Bosnia is that Belgium is a very wealthy country (2019 GDP per capita US$46,420), so it can afford to pay for inefficiency and duplication in its federal structure; whereas Bosnia is a very poor country (2019 GDP per capita US$6,109), so it cannot afford inefficient federal duplication without substantial international development support that, as time passes ever further since the war and with the world concentrating its resources on fighting the Coronavirus crisis and other geopolitical events perceived to be of greater moment, donor countries are ever less willing to provide. Bosnia’s problems have been compounded, moreover, by successive High Representatives and other international officials pressing the parties to create ever more federal structures in a push towards the centralisation of power. Thereby, these international officials imagine, their presumed reforms will diminish the importance of the mono-ethnic sub-federal institutions of government and increase the importance of centralised multi-ethnic institutions; and these officials will, when they retire or move on, leave the country in a state in which it is able to govern itself without international intervention.

A succession of High Representatives and their advisors have pursued this course because they have not always fully understood the essential permanence of a figure such as the High Representative in a consociational system of government. Centralisation compounds the problems of consociationalism, not relieves them. It is decentralisation that defuses the political pressures of consociationalism when different groups do not want to compromise with one-another, not more centralisation. Switzerland survives with an approximately consociational constitution by keeping government competences away from Bern and leaving them in the hands of the geographically varied cantons.

Not always perceiving this logic, the High Representatives have perhaps been deluded by dreams that if they can create federal structures and a centralised system of government, then the position of High Representative will not be needed anymore and the international community can exit the country. This is a grave delusion indeed, because it gets everything back to front. The reason Bosnia needs a High Representative is not to manage its mono-ethnic sub-national structures, but rather to manage the consociational central federal structures, that will be jammed, blocked and inefficient without them. With its current constitution, and ever more centralised consociational federal structures pushed by different members of the international community, the High Representative becomes ever more essential, not ever less so. The same is true with international funding, which is needed in ever greater quantities to mask the Bosnian central government’s inefficiencies.

This may be observed with a pertinent recent example. The Coronavirus pandemic in Bosnia and Herzegovina is not a crisis. It is a tragedy. With death levels recently having reached as high as 90 people per day in a country of barely four million with a fractured healthcare system, the management of which is divided between Bosnia’s lazy set of constitutional structures. There is barely a national programme of vaccinations at all. That is because the international community, almost two decades ago, pushed the centralisation of pharmaceutical regulation into a federal pharmaceutical agency that, as part of a political compromise, now sits in Banja Luka, the capital of the Bosnian Serb part of the country and some 200km away from the federal capital Sarajevo. The very location of the relevant government agency to approve and distribute vaccines is a point of political controversy.

Given that, one may be barely surprised if the agency proves incapable even of conceiving of a mass vaccination programme for the nation, that transcends ethnic boundaries. Because the political incentives of Bosnia’s federal politicians and public officials are guided in the direction of extremist opposition towards the interests of other ethnic groups, even a federal pharmaceutical agency cannot agree anything between its three constituent peoples in response to a global crisis. Hence for Bosnia to be vaccinated – and this is essential to protect the rest of Europe – the international community will soon have to establish, structure and pay for a vaccination scheme that they themselves run under the auspices of international supervision. That inefficiency is the consequence of pharmaceutical regulation and public distribution being pressed up to the federal level of a dysfunctional consociational system of government.

The perversity of a message that the way for the international community to exit Bosnia is to press upon the parties ever greater centralised government structures must, by now, be obvious. This is precisely the way for the international community to stay in Bosnia for another 25 years or more. The more the country’s government is centralised, the greater the role for a High Representative and his office as a key to unlock consociational blockage. A High Representative cannot work himself out of a job by pressing harder to create sclerotic institutions over which he will be the ultimate arbiter. Rather a High Representative with such a view of matters only guarantees his own perpetual presence until eventual war or other conflict brings the whole system tumbling down. If, this year, instead of replacing Mr. Inzko as High Representative, the international community were to close his office entirely, then the centralised structures that have been gradually built up by the pressure of successive High Representatives since 1995 would collapse. The country would find itself in chaos of a kind that Belgium, with her established reign of Monarchs, can barely imagine.

Had a decision been taken to terminate the High Representative’s office some 15 years ago – the retirement of the particularly prominent High Representative Paddy Ashdown might have been an appropriate juncture – then the country we call Bosnia and Herzegovina would look very different from the way it does today. The pre-existing weak federal structure would, one hopes, have gently collapsed to a bare minimum, as with all consociational federal structures from Schleswig-Holstein to Belgium to Switzerland. Consociationalism has always entailed very weakest central government institutions, and Bosnia has been no exception.

Under such a hypothesis, the country would be run now as three mono-ethnic territorial blocs, much as Belgium is now run, with minimal cooperation between the three blocs whenever the need arose. Bosnia would have become a minimalist central state but one that was functional in proportion to her wealth. Her three governments might have matured, to the extent that they could provide basic public services to their populaces. As things are now, there is too much in dysfunctional federal institutional structures liable to collapse, just to whip away the Office of the High Representative upon the event of one individual’s retirement. The role of the High Representative is not properly dependent upon what individual office-holders may think of the morality of what happened in the 1992-1995 Bosnian war some 25 years ago, horrendous as that war was and involving as it did the most atrocious genocide. Rather the High Representative has evolved into a constitutional office, an essential feature of the Bosnian system of government that serves as one of the principal mechanisms for cooperation between the country’s three ethnic groups.

Hence a replacement to Mr Inzko must be found. But if the international community seeks to exit Bosnia, then the mandate of his replacement must be dramatically changed. This seems essential precisely because the international community has tired of running Bosnia and Herzegovina as a proconsulship. None of the principal actors in the international community has much of a strategic interest in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Perhaps the only exceptions to this are Germany and Austria, who would likely serve to receive the greater majority of refugees in the event of a renewed conflict. (The last Bosnian war displaced some two million people from their homes.) Nevertheless the good news, such small amount as there is, is that for now no renewed war seems on the horizon for as long as the three groups are separated into different territorial blocs. Thus even fear of a refugee influx is currently a remote interest.

Germany might be interested in principle in the European Union expanding eastwards, to include Bosnia and Herzegovina. But that programme of expansion seems on hold for the time being at least, while the European Union struggles with its response to Covid and the likely economic fallouts for European Union member states. Most countries involved in the contemporary international administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina have no strategic interest in the country. Her neighbours, Serbia and Croatia, have no interest. Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, does not want Republika Srpska, the Serb part of Bosnia, trying to accede to her; Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, mutatis mutandis. The United States and the United Kingdom have no strategic interest in the constitutional structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina, particularly given British exit from the European Union. Russia has no interest in Bosnia, save insofar as Bosnian issues may become proxies for other conflicts with the West. Indeed most countries have a strategic interest in staying away from Bosnia, because there seems nothing they can do to improve matters there and hence the only thing they can achieve in remaining involved there is to be blamed if and when things go wrong.

To achieve a strategic exit from Bosnia, therefore, the international community needs to change the Bosnian constitution to remove its consociational elements. The problem with saying this, as though it were easy, is that there are many consociational provisions in the country’s constitution, including all three branches of government from the Presidency through the legislature to the constitutional court. Bosnia’s constitution was designed to be like that, by its now long-forgotten Dayton framers. The making of various changes to each of these branches of the central government structure to move away from consociationalism and towards a less sclerotic form of majoritarian federal government, with clearly delineated divisions between what is a federal and what is a sub-federal competence, will inevitably be perceived as assisting different groups in each case. Hence to eliminate consociationalism from the Dayton drafting will require a lot of give and take. And as we have seen, consociationalism restrains bipartisanship and encourages extremism. That is why the parties to the Dayton constitution have barely been able to agree to amend it so far.

The only way out for the next High Representative is to impose these constitutional reforms, insofar as he is capable, by cajoling, pressing, demanding and punishing the parties; yet being strictly fair to each. The final result will involve a substantial loss of federal competence in some areas, that Bosniaks (who demand a centralised state) will revolt against; and acquiescence by the two successionist groups, the Croats and the Serbs, to a number of principles that reflect Bosnia and Herzegovina as a single state for various purposes, in particular in the regions of foreign policy and defence. One of the problems facing any new administrator in Bosnia and Herzegovina is that very little international expertise remains. Most of those involved in the Bosnian war and post-conflict reconstruction have departed and have, like Lord Palmerston surveying Schleswig-Holstein, long forgotten the intricacies of the debates, the personalities of the individual politicians (remarkably few of whom have changed in the past fifteen years) and the traps for the unwary of which Bosnian politics is replete.

This author is one such official, finding himself trying to re-learn the long-lost art of Bosnian politics but recalling historical failed efforts at constitutional reform of 15 to 20 years ago, because the international community leaders previously pushing those reforms were not thinking about them in the right way. In the past 25 years, the constitutional reforms that have been repeatedly countenanced by the international community have been exclusively in the direction of centralisation, rather than aimed at dismantling consociationalism and in the process catalysing a process of give-and-take between the domestic parties so that all three sides feel they have gained something as well as having given something away.

If we as the international community do not proceed in this dramatically new way, then we risk the Schleswig-Holstein problem of conflicts each time the High Representative is changed or another centralising reform is attempted by international community fiat. The Schleswig-Holstein Question produced a litany of wars and conflicts in which international neighbours found themselves having to intervene. This is precisely what all the international parties really want to avoid in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The road from where we are to a stable political structure in Bosnia and Herzegovina not overseen by foreigners is a profoundly difficult one, full of risks and danger. Nevertheless if we want to exit Bosnia, this is the course we must now pursue.

The Schleswig-Holstein Question, another consociationalist puzzle, was ultimately resolved by partition of the territory and its absorption by neighbouring states, But that took place only after many decades had passed, and multiple wars had yielded no other solution. Unless we stop in our tracks and dramatically reform the direction of international community attention towards Bosnia and Herzegovina, then something akin to the Schleswig-Holstein Question will continue to infect this blighted corner of Southeastern Europe. Like Lord Palmerston, we will all be scratching our heads and trying to remember what we knew about an intractable problem, as it generates ever further unpredictable problems.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News