It all started in late April with an open letter written by a group of 20 retired French generals and published in a right-wing weekly news magazine, Valeurs Actuelles, known for its inflammatory provocations. Describing France as teetering on the edge of civil war, the letter called on France’s civilian leadership to take action so the military wouldn’t have to.

With its reference to the threats posed by “Islamism and the hordes from the banlieues”—France’s peri-urban ghettos—and a form of anti-racism that “despises our country, its traditions, its culture,” the letter was more foghorn than dog whistle when it comes to the culture wars that have wracked France over the past year. And though the retired generals did not explicitly call for a military coup, the significance of the date their letter was published was lost on no one: April 21, the 60th anniversary of the failed 1961 putsch against then-President Charles de Gaulle in response to his decision to end the war, and with it French colonial rule, in Algeria.

The letter quickly snowballed into a political controversy when Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right National Rally party, responded with approval and called on uniformed service members to lend her their support. Le Pen was roundly condemned across France’s political spectrum for seeking to politicize the military. But given that 58 percent of French respondents to one poll agreed with the letter’s assessment of the country’s woes, it was an opportunity for Le Pen, who is almost assured a place in the second round of France’s presidential election next year, to position herself once again as a fearless iconoclast willing to buck the establishment consensus.

But the story wasn’t over yet. When it subsequently emerged that at least 18 active-duty French soldiers were among the other signatories to the letter, the episode became, if not a full-blown crisis, at least a matter of concern for French civil-military relations. The military quickly announced it would seek to identify and sanction those in the ranks that had endorsed what many in France considered to be a not-so-subtle call to insurrection.

So far, so good. Civilian control over the military is sacrosanct in any democracy, but especially in France, where the homme providentiel who emerges, often from the military, in the nation’s hour of need is a deeply rooted historical trope.

It’s only when one pulls the lens back from a French-centric focus to a global view that a wrinkle is introduced into this narrative of civilian leaders rooting out a particular military mindset that sees the messy instability of a normally functioning democracy as an existential threat to the nation.

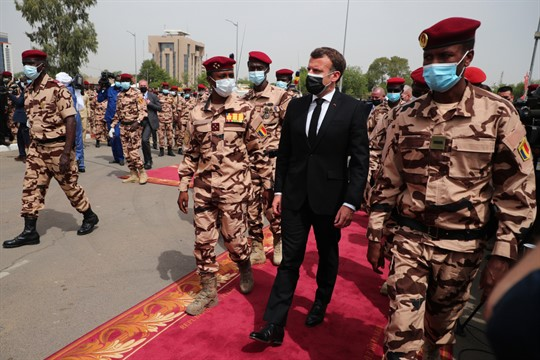

Just two days after the letter had been published, and while the fallout from it was still spreading, French President Emmanuel Macron flew to Chad to attend the funeral of Idriss Deby. The long-time Chadian autocrat had died on the battlefield the week before, fighting against the latest in a series of armed insurgencies that had arisen over the course of his 31 years in office.

Deby himself came to power through an armed rebellion that toppled Hissene Habre, the brutal dictator who was convicted in 2016 of crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture. Though he proved to be perhaps less brutal than Habre, Deby was no democrat. Nevertheless, on several occasions, the French military intervened on his behalf to help stave off armed insurgencies that threatened his rule, most recently in 2019.

To be clear, none of these uprisings promised to introduce democracy to Chad. But this was not the reason for France’s steadfast support of Deby. The explanation lies instead in the cynical calculation that often drives French—but also American—support of repressive leaders and governments in regions of strategic importance, a calculation that values stability over democracy. It is the same calculus that leads France to sell 30 Rafale fighter jets to Egypt, as was just revealed this week, despite the brutal dictatorship established there under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi; again, Washington has no lessons to teach Paris in this regard.

Recent events make clear the double standard at the heart of France’s engagement in Africa: What’s perfectly acceptable in Chad is not to be countenanced in France.Deby’s importance as a security partner for Paris was magnified by the role Chadian troops have played in France’s vast counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in West Africa, which grew out of the 2013 French intervention to stave off an Islamist insurgency in northern Mali. Deby’s soldiers, battle-hardened from their campaigns against domestic insurgencies, quickly won a reputation for effectiveness in northern Mali’s unforgiving terrain. That represented a stroke of good fortune to French military planners eager to lighten France’s own military footprint by outsourcing as much of the fighting as possible to local partners.

Chadian fighters similarly underpin the G-5 Sahel security bloc, an initiative bankrolled by France, again in the hopes of drawing down its own forces in the Sahel, which nevertheless still number more than 5,000. Deby’s troops also played a prominent role in pushing back against Boko Haram in 2015, when the Nigerian group began expanding throughout the Lake Chad region.

The circumstances surrounding Deby’s death, to say nothing of the widely acknowledged failure of France’s efforts to improve security in the Sahel, make clear what most Chadians, like most Egyptians, have known for decades: The stability provided by propping up strongmen rulers is not just fragile; it is illusory.

Nevertheless, at the same time that Macron’s government and political allies in Paris were condemning a vague and veiled threat to civilian control over the military in France, he sat at Deby’s funeral beside Mahamat Idriss Deby, the late president’s son and now head of a “transitional council” named by the Chadian military in such total disregard for Chad’s constitution that it easily qualifies as a coup.

France later walked back its support for the transitional arrangement proposed by Chad’s military, but it doesn’t seem to have had much impact on developments in N’Djamena.

The point isn’t so much that France, or the U.S., should conduct their foreign policies based solely on respect for human rights and democracy. Governments—and even analysts—don’t have the luxury of always being right in the way that advocacy organizations do. They must weigh multiple and at times competing equities that often require messy compromises not easily defended, whether morally or ethically. But in such cases, those compromises should pay off in terms of the objectives and interests they are meant to secure.

Another problem has to do with the disconnect between the values and ideals that France and the U.S. defend in theory and the priorities they pursue in practice. That hypocrisy is not lost on local populations, nor does it play well in the broader narrative of the West’s systemic competition with illiberal powers like China and Russia, as illustrated by U.S. President Joe Biden’s emphasis on a global battle between democracy and authoritarianism.

As worrisome is the tendency of any nation’s actions abroad to seep back into the body politic at home. This was on prominent display in the U.S. over the past year, as incidents of militarized policing in response to Black Lives Matter protests highlighted the ways in which America’s war on terror—and particularly its counterinsurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan—have affected its approach to domestic law enforcement and crowd control.

The juxtaposition of the recent events in Paris and N’Djamena makes clear the double standard at the heart of France’s engagement in Africa, in which democratic values are compromised in the name of stability: What’s perfectly acceptable in Chad is not to be countenanced in France. The retired generals’ letter, however, and the response to it as reflected by French public opinion polling demonstrate that this same kind of compromise can be a powerful temptation back home, as well.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News