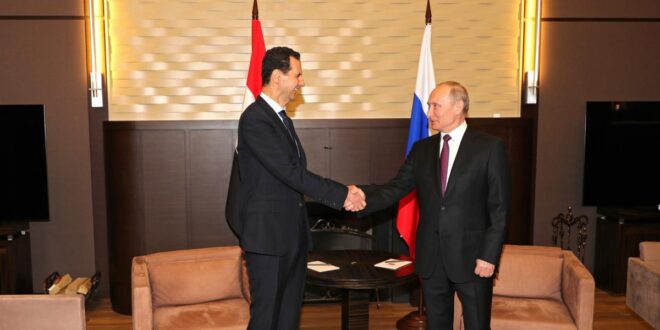

As we near presidential “elections” in Syria, it is worth exploring what interests continue to drive Russia’s ongoing military intervention in that country, which has helped the Assad regime to not just avoid being overthrown (as it seemed on the verge of being in mid-2015), but also to regain control over much of the territory it had previously lost to its various opponents. Whether Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s forces will be able to regain control over more or even all Syrian territory remains unclear. But even if this dictator—who stands to be “reelected” on May 26—fails to regain control over all of Syria, his opponents do not seem likely either to seriously threaten his regime’s survival or retake territory from it. While this represents a success for Russian policy, the situation in and around Syria remains complex for Moscow due to so many other actors pursuing conflicting policy goals there.

Besides Russia, the other actors involved in Syria include Turkey, Iran, Hezbollah, Israel, Sunni jihadist groups, Syrian Kurdish forces, the United States and the Assad regime itself. Putin’s main foreign policy approach has been neither to seek the victory of one side over another nor to resolve conflict between contending actors, but to reach some sort of accommodation with all the different contending actors (except the jihadists) and thereby give them an incentive to court Moscow even as their conflicts with other actors continue. This gives Moscow numerous opportunities to enhance its own influence through balancing between contending actors. And to the extent Russia succeeds in motivating various contending parties in Syria to cooperate with Moscow, America’s effort to counter Russian influence in the Middle East is made more difficult by the fact that America’s allies are all cooperating with Russia to some extent.

Moscow has long called for an internal peace settlement in Syria and sees a robust reconstruction effort as important for contributing to this. But Russia is neither willing nor able to pay for this effort itself. The U.N. has estimated that Syrian reconstruction will cost as much as $250 billion. Russia’s total annual foreign aid budget, though, has been running at just over $1 billion per year. Moscow, then, has sought funding for Syrian reconstruction from others better able to afford it, including the West. Western governments, though, have been unwilling to provide reconstruction funding unless the Assad regime undergoes meaningful democratic reform. But the more secure that Russia’s military intervention in Syria, which began in September 2015, has made the Assad regime feel, the less incentive it has to make democratic reforms or any concessions to its political opponents—including those who have fled Syria and whom the Assad regime does not want to see return anyway. In addition, the continued presence of Iranian forces as well as its Shi’a militia allies which are not interested in encouraging democratic reform in Syria means that Assad has important allies in resisting any Russian effort (should Moscow choose to make one) to pressure him into undertaking even minimal reform.

The continued Iranian presence in Syria also poses a challenge for Moscow. According to the “The Military Balance 2021” (published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies), in 2020 there were 4,000 Russian military personnel in Syria, while there were 1,500 from Iran, 7,000-8,000 from Hezbollah and about 50,000 militia fighters from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and elsewhere. (“Some receive significant Iranian support,” IISS noted.) On the one hand, since these forces from Iran, Hezbollah and other Shia militias have undertaken the main burden of fighting the ground war alongside Assad regime forces, Russian forces could avoid this potentially high casualty operation and focus on the air war instead. Moscow, though, now hopes to obtain funding from wealthy Arab Gulf states for Syrian reconstruction. But while Saudi Arabia and the UAE are not concerned about democratic reform in Syria like Western governments are, they (along with the U.S. and Israel) do want to see the reduction of Iranian influence in Syria. Moscow, though, is not in a position to either force or persuade Iran or its allies to withdraw from Syria, and any attempt to do so could damage Russia’s largely cooperative relationship with Iran and accelerate the simmering competition between Moscow and Tehran for influence in Damascus.

Moscow has also established a fragile degree of cooperation with Turkey in northern Syria where Ankara is supporting Assad regime opponents (including jihadists) and Turkey itself has been in conflict with Syrian Kurds whom Moscow hopes it can persuade to join forces with the Assad regime. Turkey and Russia have also been supporting opposite sides in Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh and now Ukraine. One way Moscow could punish Ankara for inserting itself into the affairs of former Soviet states is to increase its support for the Assad regime’s campaign against its Turkish-backed opponents or to help the Syrian Kurds resist Turkish forces. Doing so, however, risks damaging Putin’s larger goal of encouraging Turkish leader Erdogan’s hostility toward America and Europe.

Russian officials have long called for U.S. troops to leave Syria altogether, arguing that unlike forces from Russia and Iran, they were not invited into the country by what Moscow always refers to as Syria’s “legitimate” government. But one of the missions that U.S. forces have undertaken in Syria is ending ISIS’s control over territory there. If U.S. forces do indeed withdraw from Syria, this may lead not only to the return of ISIS to Syria, but to Russian forces having to undertake more of the effort needed to contain it.

How will Russia deal with this challenge in Syria and the Middle East more broadly? If its past actions are a guide, Moscow will try to avoid making a definitive choice about siding with any one party’s agenda against that of others. Instead, Moscow is likely to continue its efforts to let opposing sides keep each other in check and stepping in itself to keep or tilt the balance between them when this would advance Russia’s own goals.

Russia’s incipient competition with Iran over influence in Syria as well as Moscow’s desire to obtain reconstruction funding from anti-Iranian sources in the Arab Gulf give Moscow good reason to prevent the expansion of Iranian influence in Syria and even bring about its reduction now that the Assad regime’s survival is more assured. There is no need, though, for Russia to take action against Iran and its allies since Israel has taken it upon itself to do so through launching attacks on both Iranian and Hezbollah forces in Syria while going to great lengths to avoid harming Russian interests and engaging in damage control with Moscow when it does. Moscow is well aware that Tehran is not happy that Russian forces in Syria do not protect Iranian and Hezbollah fighters from Israeli attacks and even seem to facilitate them through the Russian-Israeli deconfliction process. On the other hand, Moscow may continue to calculate that because Tehran remains dependent on Moscow for arms supplies and other forms of military coordination in Syria, Tehran is not in a position to make an issue about this with Moscow.

Russia is also likely to maintain its balancing act of competing with Turkey in Syria and elsewhere while also encouraging Erdogan’s resentments toward the U.S. and the EU. If Turkish involvement in Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh, or Ukraine impinge too much on Russian interests, though, Moscow can always dial up the pressure on Ankara in Syria through being more supportive of Assad regime efforts to push back Turkish-backed Syrian opposition forces in the Idlib area or through aiding Syrian Kurds in the northeast. And if and when Moscow and Ankara come to an understanding over their differences (as they have in the past), Moscow can always dial back its support to anti-Turkish elements in Syria.

While Moscow can be expected to continue complaining about U.S. military forces remaining in Syria despite their numbers having been greatly reduced, their continued presence may actually be useful to Russia. Since U.S. forces have mainly focused on fighting ISIS, their departure would shift the burden of doing so to Russia and its allies—something Moscow does not want if it can avoid.

Some in the West have argued that one way for Moscow to try to induce European countries to provide reconstruction money for Syria would be to support maximalist Assad regime efforts to retake areas still under opposition control which would lead to renewed refugee flows out of Syria toward Europe. But instead of resulting in Europe paying for Russian-orchestrated Syrian reconstruction efforts in the hope of halting the refugee flow, this could backfire and result in European states cooperating more with the U.S. against Russia as well as arguing that they cannot provide money for Syrian reconstruction when they need to pay additional costs for dealing with more Syrian refugees in Europe.

One way for Russia to raise money for reconstruction that avoids both European concerns about reform in Syria and Arab Gulf concerns about reducing the Iranian presence there would be for Moscow to seek money from China. So far, though, Beijing has not been willing to fund Syrian reconstruction. Moscow, however, may yet be able to persuade it to do so. If China ever does decide to increase its economic involvement in Syria, though, Beijing would probably want the reconstruction effort to be undertaken more by Chinese enterprises and not Russian ones.

So far, Moscow has been able to balance between contending actors in Syria, thus giving most of them an incentive to cooperate with Moscow. The risk for Moscow, though, is that when one of the many balances it wishes to maintain breaks down, it may be unable to restore it and a greater conflict than it can control breaks out.

How should the U.S. respond to what Russia might do going forward? The first step is to recognize that even though concern for Russia has become a high priority in Washington, several of its Middle Eastern allies are less concerned about thwarting Russian ambitions than Iranian or Turkish ones they see as more threatening. Some even regard Russia as a partner, and so are unlikely to cooperate with the U.S. much in anti-Russian policies. The second step is to recognize that Washington cannot achieve all the disparate goals it has been pursuing—democracy and human rights in Syria, fighting ISIS through allying with Syrian Kurdish forces, dissuading Turkey from moving farther away from the West and toward Russia and limiting Russian, Iranian and Chinese influence in the region—but recognize the need to prioritize among them both in terms of achievability and importance. The third may be the need to be mindful about whether American success in reducing Russia’s role in Syria and the Middle East might result in increased influence there for Iran and ISIS (much like how America’s overthrow of the Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq enabled both Iran and ISIS to expand their influence there). Russia is not the only country that faces trade-offs.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News