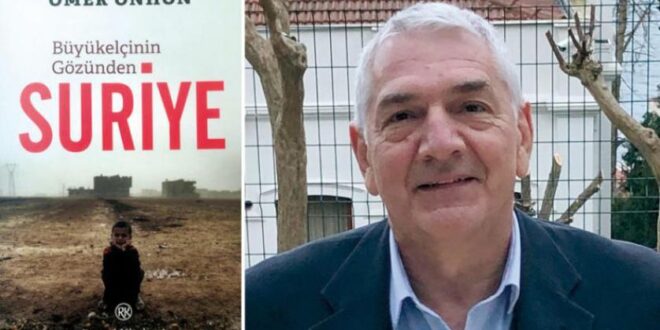

In his book, “Syria through the Eyes of the Ambassador,” Ömer Önhon recalls how the position of Turkey evolved throughout the Syrian conflict, according to Asharq al-Awsat.

The Ambassador of Turkey to Syria Ömer Önhon, who served as a political aide at the Turkish embassy in Damascus in 1988, came to many conclusions in a book he recently published, especially about the position of his country in the Syrian conflict. Önhon was appointed as ambassador there in 2009 and later special envoy on Syria in 2014 and director of security affairs at the foreign ministry.

Now retired, Önhon recounts his experience in a recently published Turkish-language book, “Syria through the Eyes of the Ambassador”. The publication details secret meetings, talks with late Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem, discussions between President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Bashar Assad, attacks against the Turkish embassy, and how the ambassador was “constantly tailed by Syrian intelligence”.

For him, the fighting may have largely ended in Syria, but the crisis there will persist for years to come, especially with the signs that ISIS and other extremist groups are reemerging. The solution, therefore, demands the execution of all articles of United Nations Security Council resolution 2254, for Damascus to impose its sovereignty throughout all Syrian territory and for the establishment of a Syrian leadership that unites all Syrians.

However, five armies and their militias deployed in Syria will not withdraw so easily. The United States, Turkey, Russia, Iran, and Israel will not pull out without guarantees that their strategic interests will be protected.

The interests of most of the countries can be met, including Russia, but Iran remains the main sticking point because it has transformed Syria into an “advanced front and a cornerstone for its regional agenda.” Tehran’s influence has grown so much that it has even become a headache to some of the military and security commanders and even the regime.

From prosperity to decline

In remarks to Asharq al-Awsat, Önhon said he was witness to critical events in relations between Ankara and Damascus, dating back to the crisis over the head of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) Abdullah Ocalan, who was deported by Syria in 1988. He also remembers the visit by then Turkish President Ahmet Necdet Sezer to Damascus to offer his condolences to Bashar over the death of his father, President Hafez al-Assad in 2000.

Sezer’s visit effectively marked the beginning of a new phase in relations, recalled Önhon. These ties “flourished when I was ambassador and Turkey was on its way to becoming Syria’s favorite country.” In November 2009, Erdogan received Bashar in Istanbul and they announced that visa requirements between their countries would be removed. “This move was the crowning achievement of these relations,” recalled Önhon.

When anti-regime protests erupted in spring 2011, Turkey carried out extensive diplomatic efforts to persuade Bashar to offer some concessions and meet some of the protesters’ demands. That way, he would have become the “enlightened reformist leader in the region and would consequently consolidate his power.”

Moreover, Önhon said a seven-hour meeting in August 2011 between Bashar and then Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu was one of the most significant examples of those efforts. Önhon was present at those talks and among the agreements was that he would visit the Hama region to ensure that pledges were being respected.

However, as disappointments with Damascus mounted and as it continued to renege on its pledges, Turkey increasingly came under pressure, especially from the U.S. and other western allies, to sever its relations with Bashar. Therefore, the position of Turkey on the Syrian conflict evolved. Indeed, in spring 2012, Ankara and several Arab countries severed relations and threw their support behind the divided opposition that would fail to unite its ranks.

Iranian frontlines

On the other side of the divide, Önhon credited Tehran and Moscow with acting fast in Syria. Iran set up its line of defenses and Shiite and Hezbollah fighters, as well as Iraqi groups and Afghan and Pakistani militias, thrust themselves to the frontlines.

It was Russia, however, that “played the greatest role in turning the tide of the war” after it intervened in 2015. It applied the same war strategy it had implemented in the Caucasus in the 19th Century and later in Chechnya in the 20th Century, noted Onhon. In sum, the strategy views every person and everything as a target. Russia’s war creed does not recognize collateral and civilian damage whereby military leaders are not responsible for their actions. It is this approach that made a huge difference, explained Önhon.

Another major factor in determining the war was the emergence of extremists in Syria, he recalled. Rather than viewing them as a setback, the regime deliberately released extremists from the notorious Saydnaya Military Prison and made them form armed groups aimed at fighting Damascus. Unfortunately, this strategy was a success. After the barbaric terrorist ISIS group emerged, the world turned its full attention to it

After repeated hesitancy in Syria, the one time the U.S. acted decisively there was when it chose the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) as a local partner, to the detriment of relations with Turkey, and the position of Ankara in the Syrian conflict continued Önhon. The ambassador speaks in his book of a “turbulent triangle” that includes Turkey, the YPG, and U.S. He also noted the Syrian refugee crisis – the worst since World War II – and how the Syrian conflict has become embroiled in internal Turkish politics, which is also rife with deep divisions.

What about Idleb?

After losing many territories, the regime, with Russian and Iranian backing, managed to recapture most of them. The latest presidential elections were held in regions held by Bashar’s forces that effectively hold less than two-thirds of the country’s territory. Regions held by the Kurdish autonomous authority in the northeast and extremist Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and pro-Ankara groups in the north and northwest were not included in the elections.

During his swearing-in ceremony, Bashar vowed to recapture territories outside regime control from the grasp of “terrorists and their Turkish and American sponsors.”

Önhon stressed that Turkey “cannot turn its back on the events in Syria. It must protect itself and at the same time, it must do all it can to end the war. In the meantime, no one can deny that Turkey, just like any other country, may have committed some mistakes.”

The Idleb province, which is home to 4 million people, half of whom are refugees, is a “ticking time bomb”. There are great concerns over the fate of thousands of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham fighters and residents should the regime, Russia, and Iran decide to wage a major military offensive there. The only place they can flee is Turkey, which is their only passage to Europe.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News