What can be done is something far easier: have the government explain to the public what it is doing and what it wants to achieve; and not just when it comes to Iran, but also Gaza

It was a coordinated assault.

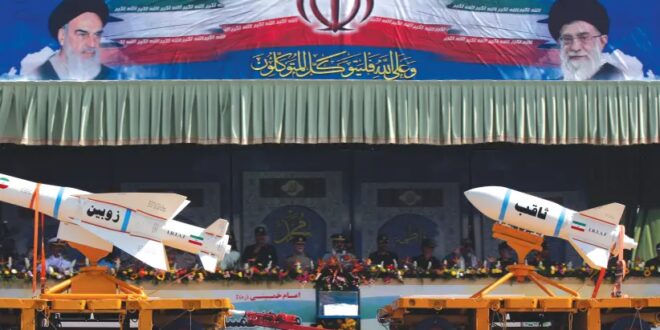

The first was by Defense Minister Benny Gantz, who on Wednesday morning warned a group of 60 diplomats serving in Israel that Iran is a mere two months away from becoming a nuclear power. Israel, he warned, would not let that happen.

“The State of Israel has the means to act and will not hesitate to do so,” Gantz said. “I do not rule out the possibility that Israel will have to take action in the future to prevent a nuclear Iran.”

Later that afternoon, comments made a day earlier by IDF Chief of Staff Lt.-Gen. Aviv Kohavi were released from embargo. Israel, the head of the army said, was accelerating operational plans against Iran, with NIS 3.5 billion of the new defense budget being earmarked specifically for that purpose.

On Thursday it was Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s turn. On his first visit to Washington as prime minister, Bennett planned to use his hour-long meeting with Joe Biden to try to convince the US president to keep up the pressure on Tehran.

While Bennett spoke earlier this week about a new plan he had crafted to stop Iran, he did not really have that much new to offer the US that was substantively different from what previous Israeli governments had asked of their American partners. Israel wants to stop Iran without needing to attack. It has long believed that the way to do that is to combine a number of measures: sanctions, covert operations, economic pressure, and steps against Iranian proxies throughout the Middle East.

What is new is Bennett himself.

One, he is not Benjamin Netanyahu; and two, he is not going to stand before Congress, as his predecessor did, and speak out publicly against a sitting president. That is why he has spoken in recent weeks about the “new spirit” that his “new government in Jerusalem” is bringing to the relationship with the United States.

Another opening that allows for a new plan is that the US has not yet returned to the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the JCPOA. Upon taking office in June, Bennett initially believed that the Americans were just weeks away from returning to the deal. But when that didn’t happen, it presented him with a window of opportunity of which he is now trying to take advantage.

That is what is new, and that is why the government is working in a coordinated way. From Gantz to Kohavi and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid to Bennett, everyone understands that as long as the Americans are not yet back inside the deal, Israel needs to use this moment to influence what happens next. It is also why Bennett speaks of the “new spirit”: he wants to buy good faith with Biden, and knows that not being Netanyahu is just not going to be enough.

Nevertheless, after all is said and done, we need to remember that Israel’s options are limited. It can continue to strike covertly at Iran, and share its vital intelligence with allies to get them to curb economic ties, but that will not be enough. What Israel would ideally like to see happen is for the US to issue a credible military threat against Iran, similar to what Gantz and Kohavi did on Wednesday.

While there is very little expectation that the US under Biden would attack Iran – especially in light of what’s happening in Afghanistan – a credible US military threat is believed to have been one of the most effective tools until now in getting the Iranians to recalibrate. In 2003, when the US invaded Iraq, the ayatollahs in Iran thought they were next in line and suspended most aspects of their nuclear weapons program.

It is a strategy that Netanyahu pushed during the Obama administration as well. He urged the president to not only up sanctions against Iran, but to also prepare the US military in a way that would make it clear to the Iranians that he was not bluffing, and that military action was not just on the table as a figure of speech.

Until today, there are disagreements among former officials on whether Netanyahu was actually planning to attack Iran, or was just bluffing and trying to get the Americans to take tougher action themselves.

Based on the threats from Israel in recent days, it could be that this is the direction Israel is once again headed. It wants to get Iranians to think it is preparing an attack, but no less important is getting the world and specifically Biden to think that scenes of Israeli fighter jets flying to Iran is a realistic option.

While the effectiveness of this policy can be questioned, there at least seems to be a coordinated strategy being led by Bennett and his government. As demonstrated on Wednesday, everyone knows their part. Gantz and Kohavi are making the threats, Lapid is working the diplomats, and Bennett is trying to get Biden on board.

Where Israel does not seem to have anything remotely close to a strategy is the Gaza Strip, which this week seemed like it was again on the verge of exploding into another widespread conflict.

Last Saturday, St.-Sgt. Barel Shmueli was shot along the border and continues to fight for his life. In the days since, the media has been full of stories of everything but the main issue: what does Israel want to do with the Gaza Strip?

We heard the recording of the conversation Bennett had with Shmueli’s father during which he bungled the border policeman’s name; we heard the radio interviews with his mother and watched as hundreds of people gathered outside Soroka Hospital in Beersheba to pray for his recovery; we learned of Kohavi’s visit to the hospital, which came after criticism from the family that no one was visiting them; and we read about the IDF’s investigation into the incident that includes recommendations on how to prevent such border shootings from happening again.

If I didn’t know better, I would think that the border protest that led to Shmueli’s shooting was an incident of strategic ramifications for the State of Israel, and not a tactical border clash (which it was) that was bungled.

The reason this happens is because Israelis don’t know what to make of the situation in Gaza. They don’t know how to process it, since their government never explains what it wants. And the reason the government never explains what it wants is because it doesn’t really know.

So instead of explaining that unfortunately Israel borders a territory controlled by a murderous terrorist organization and that conflict will not just go away, the government doesn’t say much of anything. It threatens Hamas every once in a while, saying Israel will attack on its own time clock; responds with meaningless airstrikes to incendiary balloon and rocket attacks; and allows in Qatari cash payments that it previously said it would not do.

Under these circumstances, it is no surprise that both Kohavi and Shin Bet (Israel Security Agency) chief Nadav Argaman are not particularly perturbed by Gaza today. It is blocked off by a wall, there is Iron Dome to intercept most rockets, and there is technology to detect tunnels. They of course are always preparing for a new conflict, but their focus is on other fronts, from the West Bank to Lebanon to Syria to Iran.

The question we need to ask ourselves is whether this is good enough. Should we not demand more from our government? Either introduce a plan that has never been tried that would use economic tools and incentives (for example allowing Gazans into Israel for work, or building a power plant and industrial zones for them), or, a frank explanation of how the conflict will continue and more soldiers like Shmueli will unfortunately and tragically continue to get hurt.

We know that neither will happen, since it is highly unpopular to admit that you don’t have a solution to something. It is much easier to pretend that there is one even if there isn’t.

What adds to this imbalance is the way this country digests news of an injured soldier. This is one of the “sacred cows” in Israel, an issue that is meant to be above and immune to criticism. It is an issue that cannot be analyzed in a single column and possibly not even in a lengthy series, leading to a feeling that Israelis sometimes have a harder time learning of a dead soldier than of a dead civilian.

This is the result of a number of factors. Firstly, all Israelis are meant to serve in the army. This means that almost every one – excluding the haredim and the Arabs – has served in the army and has a child who has served or is serving.

When there is war or news of a casualty, the fear sweeps across the entire nation.

There is also the changing nature of warfare, which has become standoff and almost casualty-less in recent years.

In the operation in Gaza in May, for example, no soldiers needed to cross into the Hamas-controlled territory. In total, on the Israeli side, 12 civilians were killed and one soldier. This style of warfare gives the impression that wars can be fought and missions carried out with very little price.

Then there is the length to which Israelis are willing to go to save a single soldier. On the one hand, this is exemplary, and shows the value that we as a people put on every single life. But this also leads to situations like the prisoner swap for Gilad Schalit, which saw the release of 1,500 Palestinian prisoners for one single soldier.

And so we have to ask ourselves: if the person shot on Saturday had been a farmer working his field near the border, would it have received as much attention? Would the TV stations have dispatched camera crews to the hospitals for several days in a row? Would the prime minister have called the family? Would the chief of staff had needed to visit?

We all know the answer. But this is something to ponder since it touches on the role of the military and what our soldiers are meant to do. Tactical incidents will continue to happen, especially when soldiers need to be deployed along a volatile border to protect civilians, which, after all, is their primary job.

Can this be corrected? I don’t know. But what can be done is something far easier: have the government explain to the public what it is doing and what it wants to achieve; and not just when it comes to Iran, but also when it is closer to home, along the border with Gaza.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News