For Shi’a Muslims, the highest-ranking religious authorities are known as marj’as, who serve as a reference point for emulation for laypeople (marj’a al-taqlīd). The position of the marj’a, known as the marj’aiyyah, has the exclusive right to issue religious rulings (fatwas). Since the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Sistani in Najaf has become a focal point not only for Shi’a in Iraq, but for the entire region. Sistani is now 91 years old and the question of succession is a central one — one that concerns not only Shi’a Muslims, but the wider Middle East as well. This paper aims to shed light on the future of the religious authority in the Shi’a world based on the unavoidable change after Sistani.

Introduction

For Shi’a Muslims, the highest-ranking religious authorities are known as marj’as, who serve as a reference point for emulation for laypeople (marj’a al-taqlīd). The position of the marj’a, known as the marj’aiyyah, has the exclusive right to issue religious rulings (fatwas). Every renowned marj’a is expected to publish a manual of practical guideline for religious affairs, or ar’risalah amaliyah.1

Since the Iranian Islamic Revolution in 1979 that brought Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini to power as the supreme leader of Iran, there has been a major ongoing debate over the role of ayatollahs in political life in the Middle East. Khomeini influenced many Islamic activists worldwide, especially Shi’a armed groups in Lebanon and Iraq, who considered him to be the marj’a with religious authority and the right to make decisions within the confines of shari’a law.

After the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Ayatollah Sayyid Ali Sistani in Najaf became a focal point not only for Shi’a in Iraq, but for the entire region. Sistani is now 91 years old and the question of succession is a central one — one that concerns not only Shi’a Muslims, but the wider Middle East as well. This paper aims to shed light on the future of the religious authority in the Shi’a world based on the unavoidable change after Sistani.

Shi’a Religious Authority and the Concept of the Marj’aiyyah

The majority of Shi’a identify with the “Twelvers” or “Imamate,” sharing most other Muslims’ beliefs, though with some specific and significant differences. They believe in the khalifas, which means the successors to the prophet must be descended from him. Those successors only include Ali bin Abi Talib (the cousin of the Prophet Muhammad and his son-in-law) and 11 of his descendants, which is why they are called “Twelvers.” They regard those 12 imams as sacred, infallible people selected by God to guide Muslims after the prophet passed away. Shi’a believe that the last imam, al-Mahdi (born in 869 CE), was hidden by the order of God and he is the messiah who will rid the world of injustice alongside Jesus. Based on Shi’a theology, al-Mahdi was withdrawn by Allah into a miraculous state of occultation (hiddenness) in 939 CE. According to the Shi’a literature, al-Mahdi left a testament to his followers, referring them to the religious scholars with the greatest knowledge of the religion (i.e., fuqaha or “jurists”). Thus, Shi’as believe in the clergy as the successors of their imams until al-Mahdi, the Hidden Imam, returns from occultation. As a result, the clergy has a significant role among Shi’a, in contrast to the minor one it has among Sunnis, who do not believe in the divine designation of rulers. They believe instead in the stability of Muslim nations under a single strong ruler, regardless of his religiosity. As long as the ruler does not deny any of the principles of Islam, all Muslims — including the clergy — must obey him. This puts the clergy in a secondary role in politics and governance in the Sunni realm, as their role is limited to the interpretation of shari’a law and the legitimization of the government.2

Shi’a Muslims follow a hierarchy of clerical leadership based on superiority of knowledge of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence). The mujtahids (scholars with the power of legal reasoning, or ijtihād) constitute the religious elite with the right to issue fatwas. A mujtahid may rise to the rank of a marj’a al-taqlīd, or reference point for emulation. While any senior mujtahid could plausibly proclaim himself as a marj‘a, that does not guarantee a strong following. The two most important criteria are extraordinary scholarly competence and impeccable character. Today, the major capital of Shi‘a leadership is Najaf in Iraq, followed by Qom in Iran. Iranian ayatollahs are dominant in both schools. In Iraq, there are about 20 self-appointed marj‘as, while in Iran there are about 30. In each seminary, there are five or six who are widely recognized. Most Shi’a Muslims around the world follow marj’as based in these two countries, seeking spiritual and jurisprudential guidance from them and paying khums (religious tax) to their wakils (representatives).3

Historical Background of the Development of the Transnational Marj’aiyyah

Since the occultation of al-Mahdi, Shi’a have followed local clergy who live in their communities. For a long time, there was no specific condition leading to the centralization of the position of marj’aiyyah, whereby Shi’a believers are expected to follow a transnational marj’a who is considered to be the individual most well versed in jurisprudence. It is unclear when exactly al-a’alamyah (superiority of knowledge in jurisprudence) became a condition for imitating the marj’a, who hold the title of grand ayatollah. The mandatory nature of adherence to al mojtahid-e aalam (the most knowledgeable scholar) led to the domination of handful scholars within the Shi’a religious sphere. In turn, this domination led to the establishment of an exceptional financial system, as believers are obligated to pay religious taxes to their marj’as or their local representative. The money flowing from overseas enables the marj’a to attract seminary students to his camp and these students later advocate for him when they return to their communities. This financial power leads to social power, which in turn leads to political power. Indeed, without the concept of al a’lamyah, it would be difficult for Shi’a clergy to attain the level of influence they wield.

Recent political events in Iran and Iraq have further enhanced the position of the grand marj’a as a religious authority, giving him a greater political role than the Catholic pope. The Persian Tobacco Protest of 1891 was an early example of a transnational fatwa, as Iraq’s grand marj’a at the time, Ayatollah Muhammad-Hassan al-Shirazi (1815-95), forced the Persian shah to abolish a tobacco concession granted to the British. Furthermore, the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1905-11) and the Iraqi revolt of 1920 were both led by grand marj’as. That is to say, the beginning of the 20th century was the turning point for the political role of transnational ayatollahs.

The other factor that contributed to the rise of the transnational marj’as was the increase in the number of Najaf seminary graduates who returned to their communities in the first half of the 20th century, including a number of well-educated clergy members who advocated for adherence to al mojtahid-e aalam (which is most likely to be the grand marj’as of Najaf or Qom). Thus, there are three main factors contributing to the rise of the transnational marj’aiyyah:

The concept of al a’lamyah (following the most knowledgeable scholar)

The transnational political role upon the nation state in Iran and Iraq

The new wave of Najaf alumniIn terms of al a’lamyah, it is hard for ordinary Shi’as to identify who is the most knowledgeable scholar among the marj’as. Indeed, after a scholar reaches ijtihad, there are no concrete written criteria creating a hierarchy of mujtahids. Ordinary Shi’a seek the advice of experts, the scholars who can identify a certain mujtahid as the most knowledgeable among them. Those experts frequently support the head of the school they attended or the marj’a of their allies in the seminary. “The process of becoming a marj’a, however, is very elaborate, and in many cases depends not on educational level but rather on wealth and social connections.”4

The position of marj’a is both individualistic and institutional. People follow the marj’a as an individual scholar, but the clergy who serve the marj’a (both in his major offices or in their local communities) follow a hierarchy based on their position within the circle of their marj’a. The relationship between the representatives (wakils) and the transnational marj’as is symbiotic. While the marj’a proves his superiority in seminaries (hawzas), the local wakils advocate for him and persuade their people to follow him. The local clergy members who enjoy popularity in their communities derive their legitimacy from being the representatives of the deputies of the Hidden Imam (who, according to Shi’a belief, went into occultation in 874 CE and will return at the end of this world to restore justice and peace), while the marj’as derive their legitimacy from being recognized by the local religious authorities (wakils) who advocate for them. In theory, the marj’a is superior to the wakils who represent him; in practice, however, people follow the marj’as based on the advocacy from the wakils to the grand ayatollah. That is to say, “the marj’a who has influence in the traditional hawza still needs adherents who follow his lead and put his religious rulings (fatwas) into action. For an aspiring marj‘a, the key to gaining adherents is having the right wakils to promote and empower him over others.”5

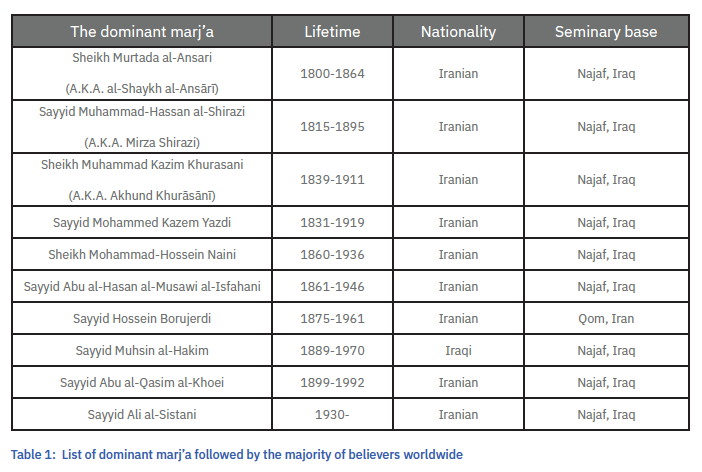

It is hard to determine who was the first sole dominant transnational marj’a. In the 19th century, al-Sheikh al-Ansārī (1800-64) was the most distinguished marj’a; his book Al-Makāsib al-muharrama (“Forbidden Businesses”) is considered one of the most prominent scholarly Shi’a textbooks for advanced students in seminary, and many subsequent marj’as published volumes of commentary on Al-Makāsib. Since then, Shi’a have had a dominant marj’a who is followed by the majority of believers worldwide. Table 1 (below) lists those marj’a.6

It is clear that Iranian clergy who have been trained in the Najaf seminary dominate the position; al-Hakim, as an Iraqi scholar who held the role, was an exception. It is noteworthy that when an Arab scholar (al-Hakim) became the leading marj’a of Najaf, the major transnational marj’a position moved to Qom (Borujerdi) before al-Hakim eventually took on the role. There were some short-term gaps between the periods of dominant marj’as, but usually the peers who compete with the major marj’a pass away shortly and the majority of Shi’a follow a major marj’a.

The Relationship between Najaf and Tehran

During the Qajar (1789-1925) and Pahlavi (1925-79) eras, the Iranian shahs showed great respect toward the religious authority of Najaf; some of them even proclaimed the emulation of the grand marj’a of Najaf. Doing so was a way for them to confront and push back against the religious authority of the Qom Seminary. The marj’a has religious authority over his followers, who are obligated to follow his fatwas. Those who imitate other marj’as, however, are free from this obligation. By contrast, the Najaf marj’a did not provide legitimacy to Baghdad’s government, which at the time was controlled by a Sunni elite. So, those Iraqi rulers had no motivation to court the traditional Shi’a authority, who also had no interest in them, especially given the financial independence of the marj’aiyyah, which is ensured by the religious taxes paid directly by worshipers.

The recognition of Najaf’s authority by the shahs of Tehran was a point of support in the favor of the Najaf Seminary. The head of state in Iran favored an outside marj’a over the local ones. Thus, the grand marj’a of Najaf increased his chances of enjoying popularity in Iran and political support worldwide. For non-Shi’a, they considered the grand marj’a of Najaf as the religious authority respected by the strong Iranian king.7

The Islamic Revolution in 1979 was not merely a change in the Iranian regime. Iranian foreign relations were also significantly affected, especially with the war with Iraq (1980-88). During the Iran-Iraq War, the grand marja’a in Najaf, al-Khoei, refused to issue a fatwa supporting the Baathist regime, while the Iranian army was blessed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who was, as the supreme leader, the chief commander of the army. Al-Khoei’s passive stance was appreciated by neither Baghdad nor Tehran. Thus, the long-term alliance between Najaf and Tehran was terminated, and the Baathist regime started to harass the marj’as without the risk of provoking Tehran. The Islamic regime in Tehran adopted the theocratic principle of velayat-e faqih, under which the faqih (jurist) serves as the general deputy of the Hidden Imam, who is authorized to act on behalf of the prophet and the 12 imams, including overseeing the governance of the country as the wali al-amr (guardian) of the Muslims. Khomeini and later Ali Khamenei imposed their will upon the Iranian public sphere as a source of legitimacy apart from Qom and Najaf. The marj’aiyyah of Najaf maintained this passive political status from the Iranian Islamic Revolution in 1979 until the collapse of the Baathist regime in 2003.

The Rise of Sayyid Ali al-Sistani

Sayyid Ali al-Sistani was a student of three former marj’as: Borujerdi, al-Hakim, and al-Khoei. He was a very close disciple of al-Khoei and one of the top mujtahids when his teacher passed away in 1992. Indeed, Sistani was the one who led the prayer on al-Khoei ‘s body in a very private funeral, which is, in the Shi’a tradition, a sign of respect within al-Khoei’s circle.8 His knowledge and close relationship with al-Khoei, however, were not the only reasons why he was able to gain the current position and standing he holds today.

During the 1980s, a number of distinguished scholars passed away. The Baathist regime executed Sayyid Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr in 1980. Al-Sadr was a young creative marj’a and influenced many clergy members who later become marj’as themselves, such as Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah (1935-2010). In addition, when the regime assassinated Sayyid Nasrallah al-Mustanbit in 1986, who was al-Khoei’s son-in-law and his substitute imam and prayer leader, Sistani replaced him in the role. Al-Khoei also brought exceptional members of the Najaf seminary to Qom either by choice or to escape the cruel regime in Iraq. Scholars such as Mohammad Hussaini Rouhani (d 1997), Jawad Tabrizi (d 2006), Wahid Khorasani, and Mohammad Sadeq Rouhani would have had a better position if they had stayed in Najaf, the major seminary of Shi’a theology.

When al-Khoei passed away on Aug. 8, 1992, Sistani was the grand marj’a’s closest disciple. The only major scholar alive in Najaf at that time was Sayyid Abd al-A’la al-Sabziwari (1910-93), who passed away a year after al-Khoei. From 1993, Sistani took on the role of grand marj’a of Najaf. The majority of al-Khoei’s wakils (representatives), including al-Khoei’s sons who run his foundations, pledged allegiance to Sistani as their new marj’a — a strong supportive action in Sistani’s favor.

During the following years, the grand marj’as of Qom passed away in turn, the most important of which were Sayyid Mohammad Reza Golpaygani (d 1993) and Sheikh Mohammad Ali Araki (d 1994). Gradually, Sistani was recognized as al mojtahid-e aalam, which enhanced his authority to be the grand marj’a for Shi’a worldwide.

Sistani’s path to becoming the grand marj’a was very traditional, as the grand marj’a is generally raised to the position either by being a strong competitor or a close disciple of the previous one. When a scholar becomes the grand marj’a of Najaf, he will most likely also become the marj’a for Shi’a worldwide.

The Marj’aiyyah in the Post-2003 Era

From the Iranian Islamic Revolution in 1979 to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the position of grand marj’a was focused on religious affairs and had a very limited role within the political realm. During that period, the supreme leader in Tehran built a strong political, economic, and social network worldwide, serving the agenda of the Islamic Republic. The Imam Al-Khoei Benevolent Foundation, which was established in 1989, was not a competitor with the Iranian network. Located in London and with 15 branches in some of the world’s most important cities, this traditional organization concerns itself with charitable and missionary educational functions historically associated with the marj’aiyyah in Najaf; they currently follow Sistani as their marj’a.9

The collapse of the Baathist regime in Iraq was a turning point in the Middle East that affected the region’s political, economic, and social affairs. The marj’aiyyah started to face new challenges with great expectations from Iraqis who had just been freed from dictatorship and faced foreign invasion. As the grand marj‘a of Najaf, Sistani carries the hopes of Iraqis to deal with the complications resulting from the 2003 invasion of Iraq, including the American military occupation itself, as well as issues like sectarian violence, political fragmentation, and corruption.

At this point, the marj’aiyyah shifted from a focus on surviving the harassment from the Baathist regime in Baghdad to observing the political landscape and interfering only in the most critical circumstances.10 Sistani is turned to for guidance and his advice is sought by politicians in times of crisis, as they expect the Shi’a population to obey his pronouncements.11 This is a reasonable assumption, since the Iraqi prime minister “needs to take enough tangible steps on reform and combatting corruption to secure a meeting with the Grand Ayatollah.”12 Since the invasion of Iraq, U.S. administrations have dealt with Sistani as “a major power broker”13 who does not exercise power but holds great influence upon the public sphere and would get involved when it is absolutely necessary. Sistani, however, approaches the political scene with the pragmatic and circumspect behavior of a civil state leader, rather than following the theocratic model of Khomeini (i.e., velayat-e faqih). That is to say, regardless of the significant power that Sistani has, he is not interested in using it to impose his will as a ruler or to get involved in governance. This attitude reflects his view of the marj’aiyyah as a religious position, not a political one. The more a marj’a gets involved in state affairs, the more potential mistakes he could make. In addition, becoming deeply involved in Iraqi politics would only put the grand marj’a of Najaf in the difficult position of choosing between two undesirable options:

Becoming involved in the political scene of other countries with large Shi’a populations, in order to maintain his role as the transnational grand marj’a.

Remaining in a passive political role, which would call into question his status as the grand marj’a of Shi’a in general, or even only among Iraqis.It is clear that neither position serves the marj’aiyyah as a transnational religious leadership. Thus, Sistani is establishing a new doctrine of the marj’aiyyah,14 which aims to balance his potential power in the host-state of Iraq with his broader spiritual leadership of the Shi’a population worldwide. Sistani has never taken any position or issued any fatwa regarding political upheaval in any country other than Iraq.15 This wise attitude should serve as an example for the future marj’as of Najaf; otherwise, Iraq and the Shi’a worldwide would face a tough future with their Arab neighbors and other regional powers such as Iran, India, Pakistan, and Turkey. Following what I call “Sistani Doctrine” should serve as the model for future marj’as to avoid potential political crises.

Sistani and the Issue of Succession

Based on the historical background provided above, it is not an easy task to succeed the dominant transnational marj’a of Najaf. Succession entails many factors beyond just religious knowledge. The strong network of students and clergy and the leaders of Shi’a communities are even more important than being al mojtahid-e aalam (most knowledgeable scholar), which is usually determined by the experts who are already or about to become mujtahids. Those experts generally support their teachers and the marj’as with whom they already have a good connection and a wikalah (certificate of representation).

One of the most effective steps for recognizing the new transnational grand marj’a is the pledge of allegiance from the transnational philanthropic foundations that serve as missionary charitable agencies associated with the former grand marj’as. The Imam al-Khoei Benevolent Foundation has pledged allegiance to Sistani by listing him as the marj’a of the organization.16 According to the fifth article of the Khoei Foundation’s constitution, “The institution is working under the supervision of the Grand Marj’a of the sect, His Eminence Grand Ayatollah Imam Abul-Qassim Al-Khoei as long as he is alive. After him, the Grand marj’a of the sect who is recognized by the majority of the respected scholars, with the approval of at least three-quarters of the members of the central committee of the institution.”17 There is another narrative stating that the foundation had pledged allegiance to Sayyid Mohammad Reza Golpaygani (d 1993), who refused to give his blessing to the foundation without having actual authority over its administration and actions. Thus, the chairman of the foundation, Sayyid Abd al-Majid al-Khoei,18 decided to declare that it would following Sistani as the grand marj’a.19

Sistani’s marj’aiyyah is not limited to the recognition of the Al-Khoei Foundation, which offered the new marj’aiyyah a supervising role in an honorary position that enables the foundation to collect religious taxes under Sistani’s auspices without giving him actual authority regarding the administration. When he declared his marj’aiyyah in 1992, Sistani’s son-in-law, Sayyid Javad Shahrestani (b 1954), was already a well-established figure in Qom. Shahrestani, who moved to Qom in 1977, founded the Ahl Al-Bayt Institute for the Revival of Shi’a Heritage in 1986. During the 12 years he spent in Qom before declaring his father-in-law as a marj’a, Shahrestani established a strong network that enabled him to promote the new grand marj’a of Najaf in Iran. The Ahl Al-Bayt Institute turned into the arm of Sistani’s marj’aiyyah in Iran and the broader Middle East. Shahrestani supervises the office of the marj’aiyyah, which is associated with 25 Islamic centers and institutes in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Germany.20 Away from the Iraqi political scene, Sistani’s office in Qom and Shahrestani are the voice of the grand marj’a worldwide.21

Sistani’s staff launched new foundations such as the Imam Ali Foundation in London, which identifies itself as the liaison office of Ayatollah Sayyid Ali al-Sistani headed by the representative of the marj’a, Sayyid Murtadha al-Kashmiri, Sistani’s son-in-law.22 Al-Kashmiri’s young brother, Sayyid Mohammad Baqir Kashmiri, is running the Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya (I.M.A.M.), Inc. located in Dearborn, Michigan and Fairfax, Virginia. While Murtadha al-Kashmiri has the title of chairman of both foundations, Mohammad Baqir, the vice chairman, is the de facto leader of I.M.A.M.23 Today, those foundations are stronger than the Al-Khoei Foundation. So, any future candidate for the position of grand marj’a must obtain a pledge of allegiance from these foundations. At this point though, Kadhim and Slavin argue that the wide network of loyalties to Sistani will not easily transfer to a successor.24

Moreover, the other sorts of networks would not play as effective a role as these institutions do. Community leaders who support other marj’as cannot avoid promoting the successor supported by these wealthy transnational institutions. For example, many Iraqis followed Sayyid Muhammad Muhammad-Sadiq al-Sadr (1953-99)25 right after al-Khoei, but this did not affect Sistani’s marj’aiyyah worldwide. In Saudi Arabia, the most senior Shi’a scholars did not declare the marj’aiyyah of Sistani until 2006. Instead, they supported Mohammad Hussaini Rouhani (1917-97), then Sheikh Mirza Ali Gharavi (1931-98), then Sheikh Jawad Tabrizi (1926-2006), and finally recommended Sistani alongside Sheikh Wahid Khorasani (b 1921) and Sayyid Muhammad Saeed al-Hakim (b 1934-2021). This attitude, held by a number of the most influential scholars in the Saudi Shi’a community, did not put any marj’as as a serious competitor to Sistani, even in the Saudi Shi’a community. As a result, the junior scholars who decided to ally with the transnational foundations of the marj’aiyyah gained more status in their communities by supporting the grand marj’a.

Iraq’s political fragmentation may also affect the new marj’as, who will inherit Sistani’s neutrality and lack of support for any particular political party. Such an attitude requires a high level of independence and popularity. The new grand marj’a needs to be popular, so politicians will consider his attitudes toward political issues, and he also needs to be independent, so that he will not need their support or worry about their anger. This includes the Popular Mobilization Committees (PMCs), which need the blessing of the marj’aiyyah as a form of social/religious legitimacy.

Countries with sizeable Shi’a minorities might be interested in having a local marj’a or at least having their Shi’a population follow a clergy who does not have significant political power, even if it is a latent power. The centrality of the marj’aiyyah causes great anxiety regarding the relationship between Shi’a citizens and their religious transnational leaders, especially in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states.26

Possible Successors and Challenges

Before 2003 the marj’aiyyah was a merely religious position providing worshipers with spiritual guidance and answers to questions of jurisprudence in matters of daily life. The post-2003 era brought Islamist parties to the Iraqi political scene, however, and they require a source of legitimacy from the ayatollahs. The Shi’a Islamist parties started their activities within Iraq at a time when the grand marj’a (i.e., Sistani) was already a well-established figure who does not need their support; indeed, they need his blessing. Thus, these parties actively work to mobilize Iraqis to follow certain marj’as with whom they already have strong established connections.

The Islamic Dawa Party does not require the supervision of a particular marj’a and they would deal with any successor with great respect, just as they have with Sistani. By contrast, the Sadrist Movement, headed by Muqtada al-Sadr (b 1974), follow Sayyid Kazem al-Haeri (b 1938), the Iraqi scholar who lives in Qom. If al-Haeri decides to move to Najaf, he would gain more followers; however, his age (83 years old) makes it unlikely he could become the next grand marj’a. The Sadrist Movement has a sense of Arabism that limits them to only following Arab — and specifically Iraqi — marj’as, which reduces their options. Sadrists, in any case, do not follow Sistani, so they are not a significant part of the equation to date.

The most effective player in Najaf would be Sistani’s office, which coordinates with the marj’aiyyah’s foundations overseas. Sheikh Muhammad Baqir Iravani (b 1949) is a strong candidate as a distinguished student of al-Khoei, Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, and Sistani. He also belongs to a family that has produced a number of great scholars, including Sheikh Fazil Iravani (1782-1885). Sheikh Hassan al-Jawahiri (b 1949) is another suitable candidate. He, too, belongs to a family that has produced a number of great scholars, including Sheikh Muhammad Hasan al-Najafi (1785-1849), the author of Jawahir al-kalam (“The Jewel of Speech”), a book composed of 44 volumes explaining the laws of Islam. Sheikh Hadi al-Radhi (b 1949) is also another suitable candidate. He, too, belongs to a family that has produced a number of great scholars, including Sheikh Radhi Najafi (d 1873). Age-wise, Iravani, al-Jawahiri, and al-Radhi are in a reasonable position to be the next grand marj’a, who will need the support of Sistani’s staff. The staff of the grand marj’a might consider one of them as Sistani’s successor in order to prepare one of Sistani’s sons, Mohammed Ridha al-Sistani (b 1962) or Muhammad Baqir al-Sistani (b 1968), to presumably take over. According to Dr. Abbas Kadhim, the director of the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative, “Sistani’s staff might pledge allegiance to Sheikh Ishaq al-Fayyadh (b 1930), the well-known Afghan marj’a. In terms of al-a’lamyah (the status of being the most knowledgeable scholar), al-Fayyadh is a strong candidate.” Despite being Afghan, the support from Sistani’s staff and the recognition from mujtahids as al mojtahid-e aalam would guarantee inheriting Sistani’s role. Supporting Iravani, al-Jawahiri, or al-Radhi would give more stability to the position, as they are all in their early 70s. They would likely have 10-20 years as grand marj’a, which might allow them time to establish a wide network of loyalties beside what is transferred to them as Sistani’s successor. Supporting Sheikh Ishaq al-Fayyadh or Sheikh Bashir al-Najafi (b 1942), the Pakistani marj’a, might risk the position because of their age, which is not much younger than Sistani himself — just like Sayyid Muhammad Saeed al-Hakim, who passed away in September 2021. In addition, the ethnic background of al-Fayyadh and al-Najafi is not in their favor; nearly all the former grand marj’as were Iranians, with some exceptions when Iraqis from Najaf obtained the position. The possibility of supporting a grand marj’a from a Shi’a minority in a country far from the major Shi’a nations (i.e., Iran and Iraq) is quite limited. The issue of ethnic background also applies to the Bahraini ayatollah Sheikh Muhammad al-Sanad (b 1961), who relocated to Najaf in 2010 and proclaimed his marj’aiyyah.

A general representative of Sistani in Saudi Arabia (who also asked to remain anonymous) argues that some of the distinguished mojtahids in Qom might move to Najaf in order to prepare themselves to be strong candidates, which is a possibility. Iravani, al-Jawahiri, al-Radhi, and al-Sanad all relocated to Najaf after the overthrow of the Baathist regime in 2003 to prove themselves as leading teachers of advanced (kharij) classes, which places them among the pillars of the Najaf seminary. In such a scenario, however, it would be more likely that the newcomer ayatollahs would succeed the next grand marj’a after Sistani, as it is too late for any scholar to establish a strong network of students and gain their loyalty.27

Conclusion

The position of the Shi’a grand marj’a is the second most important religious position in the world after the Catholic pope in the Vatican, with over 200 million people worldwide following his spiritual and jurisprudential guidance and paying religious tax to or receiving aid from him or his representatives. The position, which has been mostly based in Najaf, is now facing a serious challenge and a potential vacuum. The traditional method of succession, following the concept of al a’lamyah, gives the Shi’a elite, namely clergy, notables, and merchants, considerable power to influence their people to follow the marj’a they support. However, the most effective player in shaping the succession process is the senior staff of the current grand marj’a, who can transfer Sistani’s existing financial and political network to mobilize public support in favor of a potential successor.

There is no single individual that can be identified as Sistani’s definite successor. Things will be more complicated if a conflict occurs among the leaders of the foundations that work under Sistani’s marj’aiyyah. Such a conflict would cause a fragmentation in the Shi’a population, which would weaken the position itself. This author disagrees, however, with Mehdi Khalaji (2006), who argues for the end of the marj’aiyyah after Sistani. Khalaji’s argument is based on a biased attitude toward the revolutionary Islamic regime in Iran as the dominant player that can successfully mobilize Shi’s worldwide.28 The 40-page-long paper ignores the fact that to be a religious Shi’a, you must follow marj’a al-taqlīd. Furthermore, the majority of Shi’a — just like everybody else — are not politicized, which means they are not interested in following the supreme leader in Tehran.

This author agrees with Kadhim and Slavin (2019), who argue the uncertainty of the scenario of succession, and the certainty of the manifold ramifications of Sistani’s absence, will reverberate throughout and beyond the Middle East.29 However, despite the uncertainty of how succession will play out, the concept of al-a’lamyah will likely retain its central importance, and this favors a handful ayatollahs, most of whom are close to Sistani’s age. The major contenders, who are in their 70s, would need time until the sole nominee for the position of grand marj’a. Given this fact, it seems hard to repeat the scenario of Sistani’s own rise — he became the transnational grand marj’a within less than two years after al-Khoei passed away. According to a senior staff member of Sistani, who asked to remain anonymous, “The new successor of Ayatollah Sistani would need at least 7-10 years to be the sole transnational grand marj’a.”

The political instability in Iraq might affect the process of selecting the new grand marj’a as well. It is more complicated now compared with 1992 when al-Khoei passed away, when Muhammad Muhammad-Sadiq al-Sadr competed with Sistani in Iraq and the majority of Shi’a worldwide were following Sistani. The Iraqi Shi’a politicians, most of whom are implicated in corruption, might try to influence the process of succession, even if they won’t be able to impose a single name because they are not one cohesive unit.

Regardless of his worldwide recognition, if the new grand marj’a doesn’t enjoy enough popularity within Iraq, he is going to find it very hard to run the marj’aiyyah. This is what gives rise to the question: Will Sistani be the last legend, the last transnational grand marj’a recognized by the majority of Shi’a Muslims with the power of fatwa to affect the entire region? Even if the answer is not “yes,” that does not mean it will be an “absolute no.” That is to say, the position of new grand marj’a may continue to exist, but its stability may face a serious challenge, which might result in a series of short-term grand marj’as in the following decades until a strong figure — of course, someone in his 60s or younger30 — can once again impose himself as the uncontested leader of the Shi’a community. The key variable in this equation, I argue, will be the transnational philanthropic foundations (i.e., al-Khoei Foundation, Ahl Al-Bayt Institute, and I.M.A.M.) controlled by Sistani’s wakils. If the leaders of these foundations decide to pledge allegiance to a single figure, it is hard to imagine that somebody else will become the next grand marj’a.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News