In the last few years, the Islamic State has ramped up its operations in West Africa, rapidly fortifying its presence through its regional affiliates: Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). West Africa is particularly vulnerable to extremism and provides fertile ground for jihadist groups to expand, given the combination of weak governance institutions, limited state capacity, corruption, widespread poverty, and ethnic tensions. As the Islamic State has expanded, it has come into conflict with other jihadist actors, especially al-Qaeda’s Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), turning the region into a battleground for fierce contestation between competing extremist groups striving to assert their dominance.

As the Sahel region becomes the latest scene for jihadist infighting, this has serious implications not just for jihadist operations against local and foreign troops, but more importantly for local civilian populations. In neglected areas of the Sahel, with weak or non-existent government presence and feeble public services, groups like ISGS and JNIM are offering themselves as a strong alternative to the state, providing local constituents with essential goods and services.

Against this backdrop, this paper examines the prospects of jihadist expansion in the region and its implications for security actors and civilian populations alike. More specifically, the report investigates the role of propaganda and public discourse narratives in bolstering jihadist group legitimacy and advancing attempts by groups seeking to generate local embeddedness and mass support. In doing so, the article offers a nuanced perspective of inter-jihadist contestation, one that goes beyond mere focusing on security operations and clashes and delves more deeply into group framing and identity.

Introduction

In March 2019, the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State and its partners announced the territorial defeat of the “caliphate” after regaining control over the group’s last stronghold in Baghuz, Syria.1 Despite the demise of its physical caliphate in Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State has remained a potent threat, operating as an insurgency in both countries while the root causes that drove its establishment remain unaddressed.2

The Islamic State’s territorial defeat in Iraq and Syria forced the group to look outwards, effectively expanding its geographic reach and rebranding itself as a global jihadist movement. Since 2019, the group has ramped up its operations in Central Asia and West Africa, among other regions. The expansion of the Islamic State in West Africa is particularly alarming, with the group rapidly fortifying its presence through its regional affiliates: Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS).3

According to the 2020 Global Terrorism Index (GTI), despite the Islamic State’s overall decrease in activities in the Middle East and North Africa, the group has become especially prominent in sub-Saharan Africa. This has led to a surge in terrorism, with seven out of the 10 countries that have witnessed the largest increase in terrorism situated in the region: Burkina Faso, Mozambique, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mali, Niger, Cameroon, and Ethiopia.4

West Africa is particularly vulnerable to extremism and provides fertile ground for groups like the Islamic State to expand and flourish. A combination of weak governance institutions, limited state capacity, corruption, widespread poverty, and ethnic tensions render the region increasingly susceptible to terrorist encroachment. This is exacerbated by weak border controls and the proliferation of established networks of illicit crime and experienced smugglers. In a region with immense untapped resources, limited state presence, and a growing disenfranchised young population susceptible to recruitment, citizens’ faith in their governments is eroded, encouraging them to seek alternative — and oftentimes radical — ideologies. The security implications of these developments are proving to be catastrophic.5

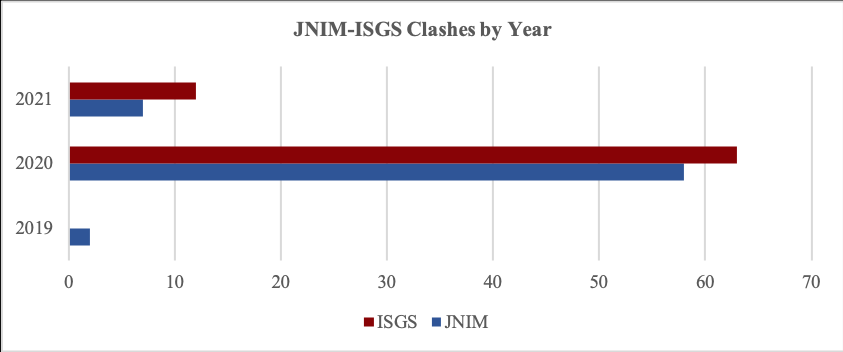

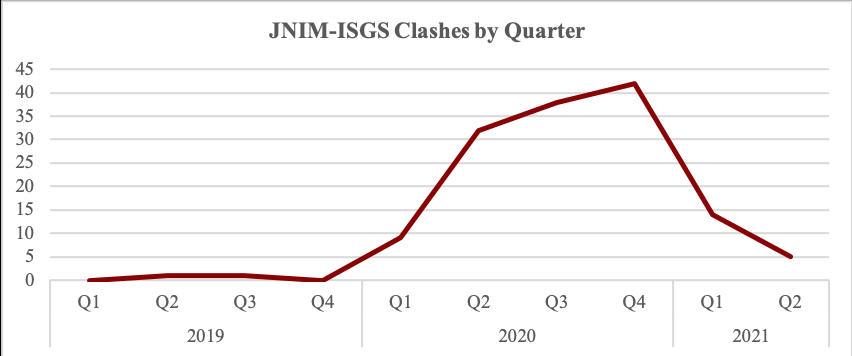

The aforementioned conditions also turn the region into a battleground for fierce contestation between competing extremist groups striving to assert their dominance. This is especially true for the “big players” in the region: The Islamic State and al-Qaeda through their regional affiliates. Most notably, the last two years bore witness to heightened tensions and clashes between al-Qaeda’s Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and ISGS. Since 2020, the two groups are reported to have clashed approximately 140 times, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED).6 This deterioration in their relationship comes after early signs of tacit cooperation and minimal confrontation between the two groups during earlier periods.

According to a study published by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, the recent fallout between JNIM and ISGS can be attributed to a number of factors, including most notably: hardened ideological differences; pressure on ISGS from Islamic State Central to confront JNIM after its formal restructuring under the ISWAP brand; and tensions arising from ISGS’s growing ambition in the region, including competition over fighters and resources.7 Despite the deployment of thousands of international peacekeepers and local and Western troops, both groups have extended their reach and the war within the region is growing rapidly.8

As the Sahel region becomes the latest scene for jihadist infighting, this has serious implications not just for jihadist operations against local and foreign troops, but more importantly for local civilian populations. In neglected areas of the Sahel, with weak or non-existent government presence and feeble public services, groups like ISGS and JNIM are offering themselves as a strong alternative to the state, providing local constituents with essential goods and services. Some civilians have even reported feeling safer living among jihadist groups than under the protection of their state security forces.9

As both groups expand their territorial footholds and vie for legitimacy in the Sahelian context, it is important to assess how each group positions itself vis-à-vis the local communities and forge relations with rural populations in the areas where they operate and recruit. In many ways, this scenario resembles what we have witnessed unfold in other conflict theaters in Somalia (al-Shabaab versus the Islamic State) and Syria (Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham versus the Islamic State), where both groups have gone head-to-head in contested zones, asserting their agendas through distinctive methods.

At the heart of the competition between ISGS and JNIM is how each will exploit local dynamics to advance their strategic objectives. Thus far, JNIM has followed the al-Qaeda blueprint of embedding itself within the broader local fabric to portray itself as a community defender, whereas ISGS has followed the more hardline Islamic State approach of framing itself as an uncompromising alternative to JNIM, attracting more vengeful recruits.10

This has clear policy implications for practitioners and scholars studying contemporary militancy in the Middle East and beyond. The Sahelian context is the latest in a series of conflict theaters where the Islamic State and al-Qaeda Central have directly competed for power and local influence. Such episodes of acute contestation between jihadist groups over resources and local control must be viewed, first and foremost, as a governance challenge, not merely a security one. The credibility of terrorist organizations in seized territory largely depends on their ability to provide a more efficient alternative to the government; this is particularly true for border zone communities where the presence of the state is limited or weak.

Against this backdrop and as the rivalry between JNIM and ISGS continues to unfold in the Sahelian context, this article examines the prospects of jihadist expansion in the region and the implications of such expansion for security actors and civilian populations alike. More specifically, the report investigates the role of propaganda and public discourse narratives in bolstering jihadist group legitimacy and advancing attempts by groups seeking to generate local embeddedness and mass support. In doing so, the article offers a nuanced perspective of inter-jihadist contestation, one that goes beyond mere focusing on security operations and clashes and delves more deeply into group framing and identity.

The article will proceed as follows. The first section provides a mapping of the jihadist landscape in West Africa and the Sahel, to anchor subsequent analysis in an understanding of the origins of Islamic State and al-Qaeda affiliates in the Sahel region. The second section lays out the article’s methodology, including the data collection and analysis strategy and a description of the data set. The third section presents data findings and captures instances of reported inter-jihadist fighting and delegitimization in groups’ public discourse narratives, thus offering insights on how ISGS and JNIM seek to advance narratives of jihadist legitimacy vis-à-vis each other as well as local populations. Finally, the article concludes with an assessment of the broader implications of jihadist expansion in the Sahel and presents recommendations for the way forward.

Mapping the Jihadist Landscape in West Africa and the Sahel

In examining the relationship between al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in the Sahel, it is important to first understand the origins of both organizations and how their presence in the region came about. In doing so, and as will be demonstrated in the following sections, it is also crucial to analyze mechanisms and pathways of change in insurgent organizations. Whereas ideologically driven groups like the Islamic State and al-Qaeda are often perceived as static actors or as prisoners of rigid ideology, recent trends have proven the contrary and taught us that such groups possess very high degrees of fluidity and agility, shifting allegiances and adjusting their organizational structures to adapt to intense threats — and the Sahel is no exception.

In March 2015, Jama’at Ahl al-Sunnah li-Da’wah wa-l-Jihad (also known as Boko Haram) leader Abu Bakr Shekau pledged allegiance to then-Islamic State caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. In an audio message, the group leader pledged to “hear and obey Islamic State caliph in times of difficulty and prosperity” and called on Muslims everywhere to follow in his footsteps.11 Shekau’s pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State was well received by Islamic State central leadership and was even celebrated in a video released by the group’s Wilayat Homs Media Bureau during the same month, titled: “The Joy of the Mujahidin of the Caliphate State With the Bay’ah of Their Brothers in Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiyyah.”12 This officially marked the inception of ISWAP and the group has since been heavily promoting its African affiliate.

The emergence of the ISGS could also be traced back to the same period, when Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawy pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in an audio message released in May 2015.13 At the time, al-Sahrawy was a senior commander in the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Morabitun, and his pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State was rejected by then-leader of al-Morabitun Mokhtar Belmokhtar, effectively causing a split within al-Morabitun and marking the birth of ISGS as an independent jihadist group.14 Al-Sahrawy’s pledge of allegiance, however, was not formally recognized by Islamic State central leadership until over a year later in November 2016, when the group officially announced al-Morabitun’s pledge and joining of the Islamic State in Northern Mali and Niger in the 53rd issue of the al-Nabaa Weekly Newsletter. The announcement emphasized al-Sahrawy’s call on mujahidin to join the Islamic State as the only way to achieve unity of jihadist ranks against global “crusader” attacks that target Islam and Muslims in the region.

Though independent in terms of the geographic scope of operations, ISGS and ISWAP are still deemed to be part of one organizational structure. ISWAP has been active in the Lake Chad Basin region, primarily operating in Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon, while ISGS is more confined to the Liptako Gourma region with operations in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Notwithstanding this differentiated scope of operations, ISGS is technically considered a sub-group of ISWAP according to the Islamic State bureaucratic structure. Throughout the group’s official propaganda, they are often referred to as one and the same.15

In 2017, JNIM, or “The Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims,” was formed by a merger of existing al-Qaeda affiliates with presence in the Sahel: Ansar al-Din; al-Morabitun; Macina Liberation Front; and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s (AQIM) Sahara branch.16 The formalized merger was announced in a video release by al-Qaeda’s al-Zallaqah Media Foundation, which featured leading commanders of the aforementioned movements gathered to display a united front and renew their pledge of allegiance to al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. This announcement effectively positioned the group as a potent jihadist movement in the Sahel region.17

The relationship between ISGS and JNIM has since not been straightforward and has instead evolved over time, ranging from purported collaboration to full-fledged clashes. Notwithstanding early signs of tacit cooperation between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda affiliates in the Sahel region, often referred to as the “Sahelian Anomaly,” recent reports point to heightened tensions and clashes between the two groups. Despite an initial period of relative calm between ISGS and JNIM, including instances of ISGS-JNIM coordination of joint raids against shared enemies, the relationship between the two groups quickly deteriorated.18

According to a study published by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, ISGS and JNIM have clashed intensely in the Mali-Burkina Faso border region. The fallout was attributed to a number of factors, including most notably: hardened ideological differences; pressure on ISGS from Islamic State Central to confront JNIM after its formal restructuring under the ISWAP brand; and tensions rising from ISGS’s growing ambition in the region, including competition over fighters and resources.19

Indeed, a careful examination of reported incidents of clashes between the two groups supports this claim and shows an upward trajectory of attacks between 2019 and 2021. As demonstrated in Figure 1.1 (above and on previous page), and according to data obtained from ACLED, ISGS and JNIM have clashed approximately 140 times during that period, with a spike in attacks during the fourth quarter of 2020. These clashes have been concentrated in Burkina Faso and Mali.20

What, then, explains this shift in relationship between the two groups, and how does each group justify and explain this spike in inter-jihadist contestation? I turn to a valuable source of insight and data: media production from the official propaganda arms of the Islamic State and al-Qaeda. Through a lens carefully curated by each group’s central leadership, the sections that follow systematically analyze and track instances of inter-jihadist fighting and delegitimization as reported by both groups in their public discourse and propaganda. This will help formulate a better understanding of the rhetoric each group employs to justify such clashes — both to its global and local audiences.

Methodology

The production of media in its different forms and the use of social media as a platform for its dissemination has become an integral part of militant groups’ operations and offers valuable information for understanding contemporary militancy. Militant propaganda offers a unique window of insight, not only on how each respective group projects its image to external audiences for intimidation or recruitment purposes, but it also shows how each group positions itself vis-à-vis its local constituents and how it sets itself apart from its direct competitors and rivals.

Through a detailed comparative discourse analysis of primary source jihadist media produced by ISGS and JNIM, I will identify key themes and trends. Propaganda has been a critical component of the recent fallout between ISGS and JNIM, as both groups have utilized their propaganda platforms to criticize their opponent and paint themselves as a more legitimate alternative.

In October 2020, al-Qaeda launched al-Thabat Newsletter, a weekly newsletter reporting on the activities of al-Qaeda affiliates around the world, as part of the group’s digital transformation. The structure of al-Thabat newsletters largely mimics the Islamic State’s long-standing al-Nabaa Weekly Newsletter, which was created in October 2015 and has provided a weekly account of the group’s operations ever since.

The data set for this report consists of all newsletters produced by both the Islamic State and al-Qaeda official propaganda since the latter launched its newsletter in October 2020, amounting to a total of 66 newsletters (27 al-Thabat and 39 al-Nabaa issues). This is complemented by leadership statements and video releases by the official propaganda arms of both groups during the same period. All propaganda pieces were collected and catalogued into a database built by the author, titled: “The West Africa and Sahel Militant Propaganda Archive.” Each piece was then skimmed for content in Arabic and catalogued, specifically focusing on operations taking place in the West Africa and Sahel regions by: ISWAP, ISGS, and JNIM.

Through systematically tracking videos, weekly newsletters, audio messages, and group statements, this study captures key differences in each group’s public discourse narrative, particularly focusing on two central themes: 1) group framing vis-à-vis local constituents; and 2) group framing vis-à-vis rival groups.

Taking into account the provenance of the dataset, it is important to approach the analysis presented here with a high degree of caution. The analysis of the group’s propaganda cannot be used as an accurate measure or reflection of the actual situation on the ground, nor the degree to which groups’ efforts advertised through its propaganda actually resonate with locals. Nonetheless, official group propaganda provides a unique window for identifying each group’s conscious effort to frame itself, both to its constituents and to regional and international actors, as well its changing rhetoric regarding how it interacts with its rivals.

“The conflict between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda in West Africa and the Sahel has not been confined to the battlefield, but has also been manifested in a fierce war of propaganda and rhetoric.”

Data Analysis

War of Narratives: The Struggle for Jihadist Legitimacy

The conflict between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda in West Africa and the Sahel has not been confined to the battlefield, but has also been manifested in a fierce war of propaganda and rhetoric. Careful examination of both groups’ propaganda shows a concerted effort to not only refute attacks by their opponent but more importantly to paint themselves as a more legitimate alternative. To capture instances of reported inter-jihadist fighting and delegitimization, the sections that follow offer an in-depth analysis of how each group seeks to advance its narrative.

Al-Qaeda’s Bid to Delegitimize the Islamic State

Al-Qaeda utilized its al-Thabat newsletter not only to report on its military operations around the globe but also as an ideological mouthpiece to advance the group’s strategic goals and objectives. On multiple occasions since its launch, al-Thabat newsletter featured special issues and front-page reports with the clear goal of delegitimizing the Islamic State in West Africa and the Sahel. These instances have been coded under two main categories: 1) Delegitimizing the Islamic State as a defender of Muslims through condemning the crimes they commit against civilians and casting doubt on their true allegiances; and 2) Discrediting ISIS as a potent jihadist force in West Africa and the Sahel by questioning its military capabilities and leadership and shedding light on the group’s persistent attempts to fight fellow mujahidin.

Delegitimizing ISIS as a Defender of Muslims

Al-Qaeda is keen to draw a sharp contrast between how JNIM mujahidin protect local Muslims in areas they occupy and the serious atrocities they say ISWAP/ISGS commit, including killing women and children, forcibly displacing Muslim villagers, carrying out road banditry, prohibiting the entry of aid and trade convoys, and coercively imposing taxes on locals after seizing control of their areas.

In a video released by al-Thabat News Agency in August 2020, titled: “A Qualitative Campaign to Expel Remnants of the Khawarij in West Africa,” al-Qaeda sheds light on the atrocities committed by Islamic State fighters against local populations in Mali, opening with a Muslim mother holding the body of a child and cursing the Islamic State fighters. The video then shows graphic footage of injured and dead children who were victims of indiscriminate ISGS violence in Mali, followed by footage of widespread military operations by JNIM soldiers to expel Islamic State “Khawarij” from central and western Mali.

It is important to unpack the significance of referring to the Islamic States as “Khawarij” or “Kharijites,” and the origins of this label in Islamic history and nomenclature. The term literally translates as “those who left” and refers to a subgroup of the followers of Ali (the fourth caliph) who later rebelled against him. They accused Ali of apostasy when the then-caliph agreed to arbitration during the civil war in Siffin, Syria in the year 658 CE to spare the spilling of Muslim blood — contravening what the khawarij deemed as God’s will. Whereas Ali initially tolerated them and allowed them to coexist in the Muslim community, their barbaric acts propelled Ali to later fight against them, ultimately culminating in the death of Ali in 661 CE at the hands of a member of the Kharijite community. The “khawarij” are deemed the first extremist group in Islamic history and are generally characterized by their strict and uncompromising views of Islam, indiscriminate violence, and a lack of rigorous Islamic scholarship and understanding.21

This characterization of the Islamic State as barbaric hardliners and Khawarij is evident in JNIM’s propaganda, which goes to great lengths to document and expose the Islamic State’s indiscriminate violence against local populations. On Nov. 15, 2020, the al-Thabat Weekly Newsletter featured a frontpage exposé of Islamic State crimes in the West Africa Province with a headline reading: “The Islamic State Conceals its Crimes in Mali, and Deputy Emir of Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiyya Personally Commits Atrocities.” The issue included a detailed report of Islamic State atrocities against civilians in northeast Mali, most notably the murder of eight local shepherds who were falsely accused of apostasy. It also included a strong condemnation of ISGS Deputy Emir Abdul-Hakim al-Sahrawy for brutally murdering an innocent local falsely accused of apostasy and spying; the article emphasized how the deputy emir killed the local in a manner that violated shari’a, by mutilating his body after his death.

Through this type of propaganda, al-Qaeda Central and JNIM strive to expose the Islamic State in the eyes of local populations, refuting their claims to be community defenders and painting them as a hardline faction that exhibits no regard for the communities they occupy. Furthermore, JNIM frames and justifies its military campaigns against the Islamic State as an effort to seek vengeance and justice for local communities — effectively positioning itself as the true community defender against the Islamic State’s indiscriminate violence.

Discredit Islamic State as a Potent Jihadist Force in West Africa and the Sahel

In addition to exposing the Islamic State’s incessant targeting of civilians in West Africa and the Sahel, al-Qaeda propaganda also demonstrates a concerted effort to discredit ISWAP/ISGS as a legitimate jihadist group, painting them as fragmented and casting doubt on their true loyalties and allegiances. This is sharply contrasted with JNIM mujahidin’s unrelenting commitment to fighting regional militaries and foreign forces in West Africa and the Sahel.

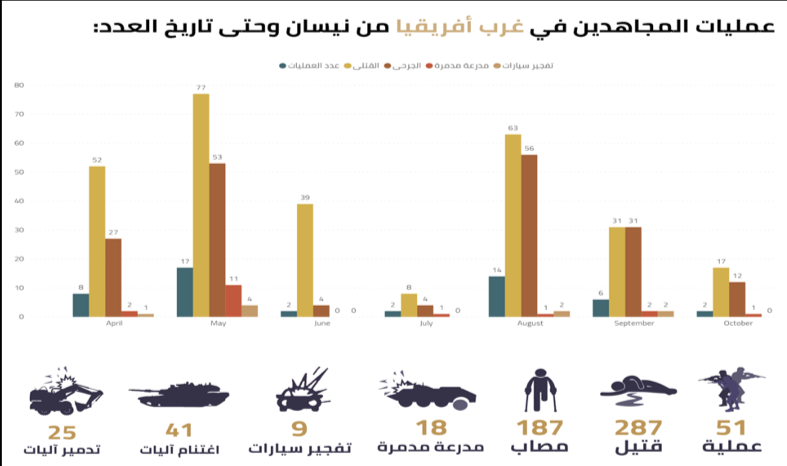

In the second issue of al-Thabat Weekly Newsletter, published on Oct. 31, 2020, al-Qaeda framed JNIM as the strongest opponent of the “crusader” French Army and its national allies in West Africa and the Sahel; the group managed to breach the borders of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, with steady encroachment on the borders of Ivory Coast and Ghana. According to the group, the period between April and October 2020 witnessed the highest number of attacks on enemy forces: 51 military operations that left 287 dead and 187 injured.

In contrast, al-Thabat Newsletter issued a harsh critique of ISWAP/ISGS in November 2020 for spending months “without a single bullet fired against the Burkinabe and Malian governments, despite easy access by IS mujahidin to their barracks and outposts,” contrasting the Islamic State’s lack of jihad with an upsurge of JNIM operations targeting French “crusader” forces and government forces in the Sahel. The issue further highlighted that, against this backdrop of increasing JNIM operations in the Sahel to expel Islamic State fighters, ISGS followers have fled and surrendered themselves to the “crusader” Burkinabe government.

Al-Qaeda propaganda also explicitly sheds light on the challenge faced by JNIM in fighting on multiple fronts — not only the “crusader” French army and the national governments of the region, but also the Islamic State. In a December 2020 issue of al-Thabat Weekly Newsletter, al-Qaeda reported a raid by Islamic State cells on a group of JNIM mujahidin returning from clashes with French forces in Gao Province in Mali, leading to the murder of 10 JNIM mujahidin. The issue emphasized how the Islamic State had halted all operations targeting the Malian government, and instead chose to expend its limited resources fighting fellow mujahidin rather than the true enemy. Al-Qaeda has also highlighted internal challenges faced by the Islamic State leadership in asserting control over its ranks in Nigeria and Somalia, as a result of internal splits and defections of fighters to Boko Haram and al-Shabaab.

This dual approach employed by al-Qaeda propaganda of delegitimizing the Islamic State in the eyes of local populations while casting doubt on its military capacities and allegiances shows that the group is not only concerned with driving a wedge between the Islamic State and its local constituents, but also with dissuading potential fighters from joining their ranks by painting them as militarily inferior and less capable compared to JNIM.

Despite JNIM Delegitimization Attempts, Islamic State Paints itself as Representative of Jihadist Movement in West Africa and the Sahel

Prior to examining the Islamic State’s response to al-Qaeda’s delegitimization campaigns, it is important to highlight the growing importance of the West Africa and Sahel region for the Islamic State’s bid to reassert itself as a global jihadist movement after the diminishing of its territorial strongholds in Iraq and Syria. West Africa and the Sahel are key to its quest to reestablish a caliphate elsewhere. This is evident not only in the group’s general narrative and reporting, but more recently in key statements by Islamic State leadership.

Upon close examination of “Harvest of Soldiers” infographics released by al-Nabaa Weekly newsletters, it is clear that the Islamic State has intensified its military operations in West Africa. Out of 40 weekly newsletters in the dataset published between October 2020 and August 2021, West Africa ranked in the top three provinces in terms of number of attacks and casualties in approximately 80% of the issues (32 out of 40).

Caliph of the Islamic State Appeals to Local Populations in West Africa and the Sahel

In addition to heightened military operations in West Africa and the Sahel, the Islamic State has repeatedly affirmed its intention to expand into the region, with propaganda prominently featuring direct pleas by the group caliph calling on local populations in the region to join the caliphate and the cause of jihad. In October 2020, the Islamic State al-Furqan Media Foundation released an audio message by Sheikh Abu Hamza al-Qurayshi, titled: “So Relate the Stories That Perhaps They Will Give Thought.”22 In the statement, the group leader refutes claims that the caliphate had been defeated and urges Muslims around the globe to remain resilient and continue on the path of jihad. He sends a strong message to fighters around the globe who have pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, assuring them that their pledge is accepted and commending their jihad. The group leader also sent a targeted message to Muslim populations in the Sahel (Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger) urging them to end their silence against their oppressive governments and wage war against the “crusaders” who usurp Muslim lands and commit atrocities against Muslim people.

In another audio message by Sheikh Abu Hamza al-Qurayshi, titled: “And You Will be Superior If You Are True Believers” (June 2021),23 the leader applauds the soldiers of the caliphate in West Africa for answering their caliph’s call to wage war against the disbelievers and defend Muslim lands and peoples. Once again, the leader sends a message to Muslim populations of the region to show their support to the soldiers of the caliphate and reiterates the call for them to join the caliphate and the ultimate cause of jihad.

Islamic State Positions itself as Ideologically Superior to Fragmented Al-Qaeda Movements in the Sahel

Now, turning to the attempts by al-Qaeda propaganda to delegitimize ISWAP/ISGS, it is quite interesting to examine how the Islamic State pushes back against such claims — whether directly or indirectly — and paints itself as a legitimate representative of the jihadist movement and Muslim populations in the region.

With regards to the split with JNIM, the Islamic State tackled the issue explicitly in multiple statements, most notably through an interview with Sheikh Abu Walid al-Sahrawy, emir of ISGS, published in al-Nabaa Weekly Newsletter in November 2020.24 The interview covered many areas of contention including al-Qaeda’s — through JNIM — declaration of war against the Islamic State in the Sahel region and how JNIM viewed the establishment of ISGS; the relationship between al-Qaeda and other jihadist factions in the Sahel; and the origin of the latest episode of inter-jihadist fighting between ISGS and JNIM. Throughout the interview, Abu Walid al-Sahrawy was keen on providing a historical account of al-Qaeda’s presence in the Sahel region, painting it as a conglomeration of various fragmented movements, driven by personal interests and fluid loyalties.

When asked about how al-Qaeda and other jihadist factions reacted to the establishment of ISGS, al-Sahrawy claimed that the news was met within widespread joy from fellow mujahidin, and deep-rooted fear by JNIM:

“With the blessing of Allah, many mujahidin in the region were happy on the occasion of their brothers pledging allegiance — first to Caliph Abu Bakr al-Qurayshi followed by Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi — and viewed it as an opportunity for renewed hope to end the fragmentation and splits that have characterized the region’s jihadist scene for almost two decades. … As for al-Qaeda factions, they have all expressed animosity and opposition against the brothers who have joined us, during the same time they were showing their loyalty to apostate nationalistic factions — even when it came at an expense of their religion. … The basis of their opposition was a fear that their followers will desert them and join our ranks, ultimately leading to the dissolution of their emirates, which they have long fought to maintain.”Al-Sahrawy even claimed that JNIM leadership prohibited their followers from viewing any Islamic State propaganda so as to not be faced with al-Qaeda’s failure on multiple jihad landscapes including Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Khorasan, and Libya.

Furthermore, and when asked about what sparked the latest episodes of fighting between JNIM and ISGS, al-Sahrawy explained that:

“JNIM leadership could not withstand the continuous fragmentation of their ranks after hundreds pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and the Caliph. … After they failed to convince them due to their lack of reason and evidence, they rushed to issue arrest orders, which propelled even more brothers to pledge allegiance to the Islamic State.”Al Sahrawy concluded the interview by stating that:

“Today their misguidance and arrogance has propelled them to follow in the apostate ‘Taliban’s’ footsteps, fighting the monotheists and chasing the mirage of negotiations with the apostates, seeking the approval of idol worshippers, even if it means fighting the people of Islam.”This type of rhetoric and defense of group motives by ISGS, paired with discounting the threat of JNIM and painting the group as fragmented and interest-driven, shows that the group leadership felt pressure to clarify its position and justify its motives in the region. Whether or not this emerged in direct response to JNIM’s smear campaigns against ISGS is difficult to tell. Still, it clearly proves that the group does not take its competition with JNIM over fighters and resources lightly, and is adamant about painting its opponent as a less worthy competitor.

Islamic State Framing vis-à-vis Local Populations

Islamic State propaganda also reflects a recognition that securing the support of local communities is as important to its bid to expand its reach in the region as attracting military recruits. In contrast with JNIM claims of atrocities committed by the ISWAP/ISGS against local populations, the Islamic State propaganda is eager to frame its relationship with its local constituents in a positive light. A key element of this effort is framing Islamic State efforts as a direct response to local needs — primarily security needs, a pressing issue for populations in West Africa and the Sahel in light of weak or limited state presence.

In May 2021, al-Nabaa Weekly Newsletter featured a frontpage report on the implementation of hudud punishments25 against road bandits by ISGS, after incessant local complaints of banditry operations taking place on the route linking between the Gao and Ménaka regions in northern Mali.26 Another al-Nabaa issue published during the same month featured a report by the emir of the Zakat Diwan in West Africa Province highlighting how local zakat givers welcome zakat collectors with grace and generosity, happy to implement their religious duty to give alms: “Whereas the disbeliever regimes impose fraudulent taxes that usurp Muslim money, Muslims living under Islamic State rule earn their living without the fear of their money being usurped under manmade laws, and instead implement the duty dictated by God to give zakat to be distributed amongst their Muslim brethren in need.”27

This process of aligning group narrative and operations with local differences and grievances is a critical aspect of the Islamic State’s framing techniques, achieved through signaling to local constituents that the group is actively working to address their daily needs and concerns. Jihadist groups’ twin interests of staying true to their ideological beliefs while ensuring civilian compliance are not always compatible, and groups often find themselves faced with the pressure of reconciling the gap between retaining their ideological identity and maximizing civilian compliance through service provision and other governance tools.

The Sahel: A New Theater for Inter-Jihadist Contestation?

It is important to note that episodes of inter-jihadist contestation between al-Qaeda and the Islamic State such as in the Sahel region are not a new phenomenon; they do not emerge in a vacuum and have also occurred in Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan.

In Syria, this scenario played out quite vigorously between al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. The 2011 political upheaval following the Arab Spring uprisings across the Middle East provided both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State with an unparalleled opportunity for growth and expansion. With both groups adopting divergent models of jihadist militancy — the first following a softer gradualist approach and the latter espousing a more hardline, ultra-violent model of jihadist extremism — the 2011 political upheavals also created the space for both groups to assert their power to emerge as the dominant representative of global jihadism. This ultimately resulted in an intensive dynamic of enmity and contestation manifesting in acute in-fighting between the two groups in Syria since 2014.28

This dynamic of intense contestation also further played out between Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the Islamic State. Previously known as Jabhat al-Nusra, this former al-Qaeda affiliate has rebranded itself twice — first as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (JFS) in July 2016, and later as HTS in January 2017 — in a relentless effort to expand its power and present itself as a sustainable model capable of continuing the fight against the Assad regime. As part of its bid to expand its local roots and embed itself within the broader Syrian revolutionary movement, HTS positioned itself as one of the staunchest opponents of the Islamic State within Syria, launching multiple security operations and arrest campaigns aimed at tracking down Islamic State sleeper cells, confiscating their weapons, and arresting and killing their fighters and key leaders and commanders. This conflict between the two groups also manifested in the propaganda sphere, with vicious campaigns through which HTS portrayed itself as a legitimate non-terrorist actor, especially in the eyes of local populations.29

In Yemen, al-Qaeda and the Islamic State have gone head-to-head through the two groups’ regional affiliates: al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State’s Yemen Province, exacerbating an already-precarious humanitarian situation and causing further destabilization and an escalation of violence at the local level. As both groups battled for territorial control and recruits, they engaged in fierce competition both on the physical and virtual fronts, by launching attacks and martyrdom operations in addition to propaganda campaigns designed to showcase each group’s strength and relative power and delegitimize its opponent. Central to both AQAP and the Islamic State’s tactics in their bid for control in Yemen was a deliberate exploitation of ungoverned spaces and an entrenchment in local power rivalries.30

Most recently, in Afghanistan, the two groups have also been engaged in serious contestation, most noticeably against the backdrop of the peace deal between the Afghan Taliban and the United States, and the subsequent U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. With al-Qaeda closely bound with the Taliban due to ideological alignment, relationships forged through common struggle, and intermarriage, the Islamic State Afghan affiliate, Wilayat al-Khorasan, stands as their avowed opponent. After a considerable rise in Afghanistan’s eastern provinces of Kunar and Nangahar between 2014 and 2016, the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP) has since suffered a series of military setbacks at the hands of U.S. and Afghan military operations, in addition to a separate military campaign by the Afghan Taliban targeting the group.31 Since June 2020, however, the group has increased its attacks and is targeting disenchanted al-Qaeda and Taliban recruits by positioning itself as the sole rejectionist group unwilling to negotiate with the West.32 The Islamic State propaganda has also on multiple occasions denounced the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan and has criticized al-Qaeda’s alliance with the “heathenistic” Taliban despite its “clear deviations and apostasy.”33

Indeed, since the abrupt U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, ISKP has been taking concerted steps to undermine the Taliban’s takeover of the country. On Aug. 26, ISKP claimed responsibility for a deadly attack on Kabul airport that killed 13 U.S. service members and dozens of Afghans.34 This attack, which was featured on the front page of the Islamic State’s weekly al-Nabaa Newsletter released a few days later, was highlighted by the group as a definitive blow to the U.S. and its collaborators.35 More recently, on Sept. 18 and 19, ISKP has also claimed a series of IED attacks carried out in Jalalabad against the Taliban, allegedly killing and wounding over 35 Taliban members.36 With mounting fears surrounding Afghanistan becoming the new safe haven for global jihadists, and against the backdrop of the U.S. withdrawal and Taliban takeover, ISKP could stand to benefit from the rapidly unravelling situation to bolster its stature and act as a spoiler to the peace agreement, attracting more followers and boosting its operations.

Together, evidence presented in this section clearly demonstrates that the schism between al-Qaeda and the Islamic State did not emerge in isolation, but rather is part of a broader trend of enmity and contestation as the two groups battle to paint themselves as the dominant and legitimate representative of the jihadist movement worldwide. This, in itself, is a lesson learned and should be factored in when devising counterterrorism responses to curb their expansion and neutralize the threat they pose.

“Security-based counterterrorism responses, though necessary, are by no means sufficient to effectively deal with the multifaceted threat that presents itself today.”

Implications of Inter-Jihadist Contestation in the Sahel

No matter the difference in approach or ideology, central to the jihadist groups’ bid for power is ensuring some degree of local compliance and support. And while it is true that a group’s relationship with other contenders may not be directly linked to how well it is able to forge ties with local populations, the presence of local challengers competing with the group for resources, territory, and community support definitely makes this task much harder to achieve. Thus, it is important for the group to assert dominance and crush rivals that challenge its legitimacy or discredit it in the eyes of the local population. Evidence from the preceding sections unambiguously demonstrates that asserting dominance and discrediting rivals is a deliberate strategy sought out by both ISGS and JNIM.

The new reality of intense competition between the Islamic State and al-Qaeda in the Sahel region from 2020 onwards, exacerbated by pre-existing structural vulnerabilities and drivers of violence, is forcing local communities (especially in border areas) to seek protection of either ISGS or JNIM from attacks by the other group or government-affiliated militias.37 Inter-jihadist contestation will also continue to heavily shape and influence conflict dynamics and outcomes in the Sahel region.

While many actors may hope that such episodes of inter-jihadist contestation can contribute to the weakening of such groups’ ranks and the depletion of their limited resources, effectively diluting the threat they pose, others contend that this is not always the case.38 A prominent body of scholarship maintains that when armed groups directly compete for recruits and the support of locals, they will engage in a process of “outbidding”: incrementally employing increasing levels of violence to demonstrate their commitment and relative power vis-à-vis competing organizations.39 Such episodes of inter-group competition can also incentivize group innovation, augment recruitment, and push civilians to pick a side among the warring groups — inevitably contributing to the longevity of the conflict as well as the endurance and adaptability of competing groups.40 This risks further complicating the conflict landscape and destabilizing an already-fragile region.

Beyond Counterterrorism: A Pressing Need to Rethink the Response to the Threat of Jihadism in the Sahel

The proliferation of jihadist groups in the Sahel — be it al-Qaeda or the Islamic State — represents first and foremost a governance challenge, and a failure to address this will only fuel grievances and prolong an already protracted conflict. While Sahelian states are heterogeneous and each faces diverse challenges, they also share a legacy of structural vulnerabilities, weak governance capacity, and limited state presence (particularly in rural areas). The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated and magnified these pre-existing threats, compounding structural weaknesses and pockets of fragility, and inadvertently provided jihadist groups with an unparalleled opportunity to expand their territorial footprint, augment recruitment, and position themselves as alternative service providers vis-à-vis the state.

This calls for a need to rethink the degree to which counterterrorism operations can be relied on as the best solution for a multifaceted and complex challenge extending well beyond the security realm. At the core of the challenge is a deep-rooted lack of popular trust in the government that has fomented over decades; this is especially true at the local and communal levels, where the presence of the state is limited or non-existent. Research makes clear that accumulated grievances and limited confidence in governments are commonplace in many regions across the African continent, particularly those with the highest incidence of violent extremism. Shared experiences of neglect, multidimensional poverty, and lack of access to basic services such as education and health care are among the predominant drivers that propel individuals to join jihadist groups.

Security-based counterterrorism responses, though necessary, are by no means sufficient to effectively deal with the multifaceted threat that presents itself today. Counterterrorism measures must be complemented by a preventative approach based on good governance and inclusive, sustainable development that addresses the structural drivers of extremism and terrorism. Preventative efforts at the local level need to focus on strengthening community cohesion and rebuilding the frayed social contract. A failure to anchor counterterrorism operations in complementary and mutually-reinforcing preventative efforts is short-sighted and may ultimately lead to counterproductive outcomes.

In the context of complex and protracted conflicts, there is a pressing need to reexamine the role of counterterrorism and acknowledge its limits. Likewise, there is a growing imperative to reconsider international support and intervention by external partners. Indeed, international governments and organizations will continue to view engagement in the Sahelian context as critical, but defining the parameters of such engagement is incredibly important and must be reassessed.

To avoid the repetition of mistakes of the past, a shift in paradigm must take place, one that gears away from highly-militarized responses and toward a more holistic approach that effectively meets local development and security needs. National governments must assume greater ownership of their region’s problems and take deliberate steps to regain the trust of local populations. Only then will efforts to slow down jihadist infiltration be successful.

Critical to this endeavor is cultivating stronger ties with local communities, which represent the first line of defense against extremist ideology; they play a critical role in addressing both real and perceived grievances and preventing violence. Governments must therefore exert a deliberate effort to engage with communities and win back their trust. Participatory approaches that entail dialogue with religious and tribal leaders as well as civil society actors are critical to the success of designed interventions. Local actors’ participation and commitment must not be regarded as a routine exercise; rather, they should be fully and effectively included as positive agents of change and pillars of resilience.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News