The analyses in this paper show that the next German government will also be a pro-European one. There are, however, various necessary changes when it comes to European integration, where the new German government could play a constructive role.

Germany, the EU’s largest member state, went to the ballot box on 30 September to elect its next Chancellor. A traffic-light coalition of three (SPD, the Greens and FDP) is expected to come out of the negotiations, with different preferences when it comes to the future of Europe. This analysis reviews the various positions of the country’s political parties when it comes to their differing ideas on European integration and provides some policy recommendations for the road ahead.

Analysis

Germany went to the ballot box for the election that closes the Merkel era, although she will remain in power until the new Chancellor takes over. The election results and coalition-making conundrum will be on the table for days and weeks to come. Whoever is to lead the next German government has the challenge to live up to Angela Merkel’s legacy. She has gained a reputation as a crisis manager and brought to perfection the European integration’s golden rule of settling for the minimum common denominator. This was not necessarily always the best for all EU member states and policy areas. In several crises -such as the Eurozone crisis that almost pushed Greece out of the Union or the irregular migration flows in 2015 that ended up with a disputed deal with Turkey- she had her way: the German way. She also did well on many occasions when it came to the EU’s overall prosperity. In 2020, it was she and the French President Emmanuel Macron who opened the way for the most ambitious recovery fund: Next Generation EU. The road ahead when it comes to the EU’s future will be no less bumpy. The new leader of the largest member state will soon face important decisions of his own. There is only a little time to train for the job, since the list of open questions is so long: from what to do with fiscal rules to relations with China, from the continuity of Next Generation EU to the European Green Deal or the migration pact.

So what is in the German ballot box for Europe? Continuity or change? One way of answering the question is to assess the different preferences between the partners of a possible Ampel (traffic light) Coalition(Social Democrats -SPD-, together with the Greens and Liberals -FDP-) in a comparative manner. As currently neither the Jamaica Coalition (Christian democrats -CDU/CSU-, the Greens and the FDP) nor even an eventual Grand Coalition of SPD and CDU/CSU can be completely ruled out, the Union of Christian Democrats is included in the analysis. This comparison will be reviewed under three headings: (1) the economy, finance and the environment; (2) foreign and security policy and external relations;and (3) institutions and values. Furthermore, due to their high relevance, the paper will also discuss the possible distribution of ministry portfolios among the coalition partners. Overall, the aim is to shed light on the connections between the elections, the formation of coalitions and the future of European integration.

An election-day snapshot

Germany’s election results have been very much in line with what was indicated by public opinion polls. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) led the polls at 25.7%. The second largest political force, the CDU/CSU, recorded a substantial loss but was right behind at 24.1%. The Greens came in third at 14.8%, followed by the Free Democratic Party (FDP) at 11.5%. The far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) lost votes but still came in at 10.3%. Already before the election, however, other parties had ruled-out a possible coalition with the AfD, making it irrelevant to coalition formation. The far-left Die Linke ended up below the national threshold at 4.9% but made its way into the German Bundestag thanks to its three directly-elected representatives. Still, a so-called ‘red-red-green’ coalition of SPD, the Greens and Die Linke is no longer an arithmetical option.

An important component of the electoral race has been age. Younger Germans have voted for the Greens and the FDP, while their elders have maintained their loyalty to the SPD and CDU/CSU. This means that at least the younger generations are looking for some change, rather than continuity, and the winning coalition should take this into consideration while defining its priorities. Even more so, as the Greens and FDP are acting as kingmakers in the process. At the same time, negotiations between the latter can be expected to determine both the scope and content of change in Germany, since they have differing stances on various issues, mainly in the area of economy and finance.

Having said that, election results indicate a voter preference for the Ampel-coalition because all three parties involved, SPD, FDP and the Greens, are those that have increased their share of the vote compared with 2017. Additionally, the SPD has won the election in a more traditional sense, gaining the highest percentage of votes. Thus, it can be assumed that the traffic-light coalition is likely to be the way forwards. Given that there will be three parties in the government with rather different positions, the coalition agreement will be an important issue to decide during the mandate. Additionally, almost one third of the members of the Bundestag are newcomers, while a quarter are aged under 40. This will surely involve a new form of institutional socialisation. Having said that, the new government is not expected to involve complete break.

Whatever the result of the coalition formation process, the next German government will be pro-European. How ambitious it will be concerning Europe remains to be seen when it comes to: (1) economy, finance and the environment; foreign and security policy, with a special focus on transatlantic relations and China; and (3) institutions and values. The government’s position in these three areas of importance will very much depend on a correct distribution of portfolios.

What’s in it for Europe (1) greener economy and finances

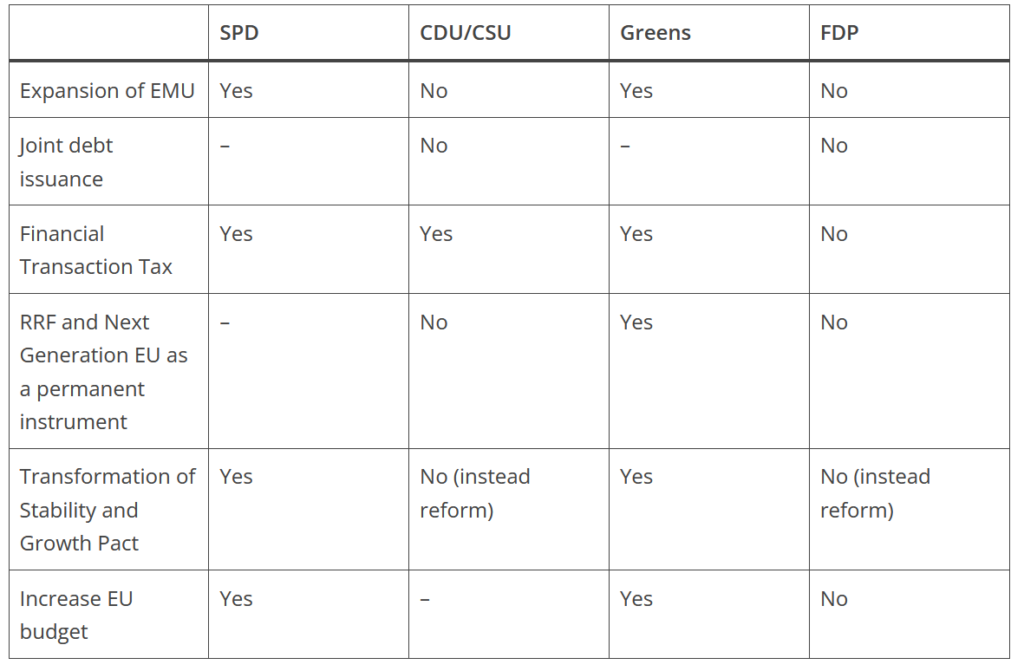

In terms of Economic and Monetary Union and of financial and economic policies, the fault line runs between the SPD and the Greens on the one hand and CDU/CSU and FDP on the other. In the event of a traffic-light coalition there will be much give and take. One of the key questions for the new German government will be its stance on the continuation of Next Generation EU. Issuing common debt and the deadline to have the Stability and Growth Pact up and running again are crucial for the future of integration. On the one hand, the SPD and the Greens plan to transform the latter into a sustainability pact that focuses to a greater extent of facilitating investments. The FDP, on the other hand, has been quite hawkish about its promise to keep the rules intact, a position shared by the CDU/CSU. In any case, the need for spending not only in the green and digital transition but also in public infrastructure is uncontested. This should lead to a certain balance.Figure 1. Policy positions of possible coalition partners in economy, finance and the green transition

The key difference between Jamaica and Ampel in this respect are the SPD’s promises as regards the future of the welfare state, pension system and personal welfare of all Germans. Taking into account the spirit of the EU since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is safe to say that social policies will be very much on the table. The need to invest more in public infrastructures became even more visible after the summer. How they will be financed is the key, and another fierce debate awaits the coalition partners. The decades-long tension between market and state is inevitable in an Ampel coalition.

Another issue in this area is the green transition. It is the Greens that explicitly demand a ‘climate-government’, but the goal of achieving climate neutrality in the EU by 2050 or even before is promoted by all of the main parties. The differences concern the means of achieving such a goal. The FDP and Greens both focus on emissions-trading systems, but while the Liberals favour a market-based approach the Greens aim for state regulations and the taxation of CO2 border adjustments or plastics. While the Greens generally promote EU-wide taxation, including large digital corporations, that would help increase the EU budget, the FDP generally rejects EU taxes. The Ampel coalition might nevertheless set the preconditions for a greener economy as the SPD shares the demand that the EU receives the revenues of CO2 border adjustments.

Taking all these fault lines into consideration, there is no doubt the Finance Ministry will be very much under demand among the coalition partners. The FDP’s leader Christian Lindner has been very vocal about this, while Robert Habeck from the Greens is also hovering around the position. Given the need for a greener economy and the Greens’ desire for a climate-friendly government, there is also a strong link when it comes to the Ministries of the Economy and the Environment, and clearly for their areas of competence. Another key issue is which Minister will represent Germany at ECOFIN and at the Euro Group. This will also define Germany’s stance in the Council. The negotiations’ end result will very much set the tone.

What’s in it for Europe (2): foreign and security policy and external relations

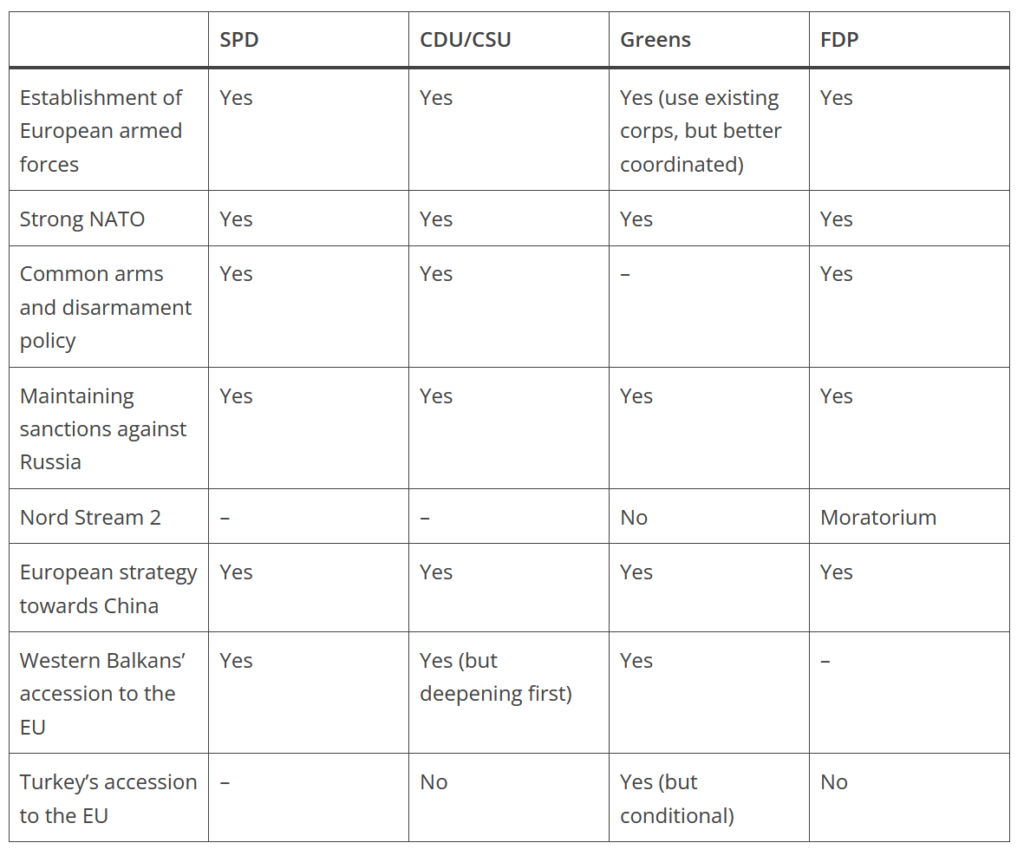

Political parties have been much criticised for their lack of debate when it comes to foreign and security policy or European policy during their election campaigns, including the televised pre-election debates. Looking at Figure 2 below, one explanation could be that there are simply not enough differences between the policies of political parties to campaign over it. When it comes to foreign and security policy, and external relations, however, there are various issues at stake. The crucial and key determining fact that should be borne in mind is all the changes in the world order that are being witnessed these days. This means that, even if the new German government would like a continuity in certain dossiers, some changes and important steps forward are naturally required.Figure 2. Policy positions of possible coalition partners in foreign and security policy and external relations

On transatlantic relations, all political parties continue to be committed. There are clear declarations in the party manifestos when it comes to the importance of NATO and stable relations with the US. Historically, there has been as certain reluctance among the German military establishment on anything that might weaken transatlantic relations. This why, in general, Germany has never been too enthusiastic about –or even contrary to– European strategic autonomy. The preparation of the Strategic Compass has been a platform to discuss various issues with European partners. Beyond the strategic autonomy debate, however, there is the issue of increasing the Union’s resilience in the years and challenges to come. Both military and economic dominance in key strategic regions of the world should be a topic on the table. An active push for consolidating alliances in the Indo-Pacific is very much needed.

On China, every party promotes a strategy based on a dual approach: being tough where needed and establishing cooperation where it is beneficial. The Greens are the only party that clearly refer to the human rights issues and the situation of the Uighurs in China in their programme. Having listened to FDP representatives in various debates, this position seems to be shared by the Liberals. The key issue is that relations with China are so much more than only foreign policy. The links between the policy on China and the economy in general, and industrial policy and climate policy in particular, are also at stake. Both the Greens and the Liberals criticise the EU’s investment deals with China. This means that regardless of an Ampel or Jamaica coalition, change might still be expected. Still, how the portfolios are to be distributed between the parties –in terms of who heads the Federal Foreign Office or the Ministry of the Economy- will play a key role.

Russia is another issue of interest. No coalition will, or even could, undo NordStream II, but while the parties of the previous grand coalition, the CDU/CSU and the SPD, remain silent on the issue in their party manifestos, the Greens openly oppose it -also for climate and environmental reasons- and the Liberals suggest a moratorium for the pipeline as long as Russia fails to improve its human rights policy, including the Navalny case. On the question of continued sanctions against Russia, there is more unity across the relevant parties. Positions merely change in terms of nuance: while the Greens consider even stronger sanctions if need be, the SPD clearly focuses on strengthening dialogue on all levels as a means of facilitating a possible termination of sanctions. But as long as the annexation of the Crimea remains unresolved, there is not much chance of any change.

On Turkey’s accession to the EU, all parties except the Greens aim for an alternative format for the EU-Turkey relationship. While the CDU/CSU and the FDP clearly out rule Turkey’s full membership in the EU, the SPD is less explicit and merely states that the current focus should be on an EU-Turkey Dialogue. The Greens commit themselves to accession as a political –though currently unrealistic- goal. They demand comprehensive reforms in Turkey in terms of democracy and the rule of law as well as a return to good neighbourly relations. Regarding the EU’s enlargement policy and specific accession processes, governments act according to the pacta sunt servanda principle. The new government can be expected to follow the same line. Still, given the complexity and conflict that has determined the EU-Turkey relationship particularly over the past few years, this dossier needs to be discussed between the European partners for years to come.

What’s in it for Europe (3): institutions and values

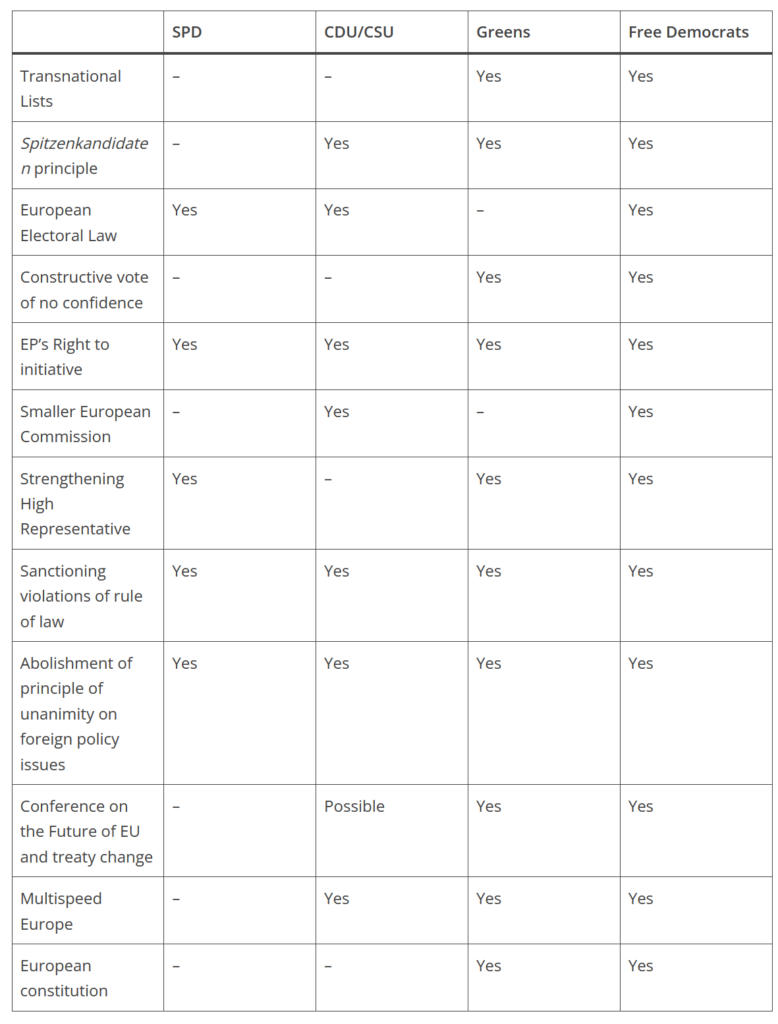

A survey of the party positions on the future of the EU in terms of its institutional set-up and values highlights the potential for change and reform. There does not seem to be a firm opposition to either of the reform issues currently present in the European debate in any of the respective parties. This means that these issues will not be an immediate German priority but, when the time comes, neither will they be very much disputed.Figure 3. Policy positions of possible coalition partners on institutions and values

One of the toughest issues in the next government’s list is how to defend the rule of law within the EU and what to do with Poland and Hungary. All relevant parties are strongly committed to defending European values, including democracy and the rule of law. The party manifesto of the Greens highlights the need for an EU mechanism for democracy, the rule of law and fundamental rights as well as for an EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

In view of the EU’s institutions and values it can be expected that the new government will continue the strongly pro-European vocation for which Germany is known. This also includes a broad support for the Conference on the Future of Europe. Treaty changes as a result of the Conference are not excluded by the parties. In spite of this general support for the Conference, the German government has so far not managed to define a clear position and it is unlikely that the new government will have a firmer stance right away. Having said that, it is still quite important to underline that political parties have stances on institutional debates in the EU, be it transnational lists or the EP’s right to initiate legislation.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

Merkel was lucky to enjoy a relatively stable domestic environment during her 16 years in the Chancellery. The next German government will be more divided than usual. Striking a balance between many priorities is also in the EU’s nature. Thus, the new German Chancellor should exercise this skill both in the domestic and EU spheres. A key question is if foreign policy will continue to be made in the Chancellery. Angela Merkel shaped both European and foreign policies. Having three coalition partners this time around may require more cooperation between the various Ministries. The changing nature of foreign policy could lead to more consensus building.

The analyses in this paper show that the next German government will also be a pro-European one. There are, however, various necessary changes when it comes to European integration, where the new German government could play a constructive role. The following recommendations could be useful to guide the new government:

Starting at the local level, the new German government should try to emphasise to its own public opinion the commonalities between German and European priorities rather than their differences. This would secure Germany’s commitment to the integration project for the years to come. Fighting against climate change and the digital transition are important items that could lead to synergies at both levels.

The chemistry between Berlin and Paris will also play an important role when it comes to the future of European integration. Despite structural differences between France and Germany when it comes to policy making, the need for cooperation is clear. However, while doing so, Berlin should not leave Rome and Madrid behind.

The new German government should look for ways to put its weight behind the European Commission when it comes to important dossiers such as climate change. Intergovernmental leadership is good but supranational institutions should be supported. The Europeanisation of EU policy should be an aim for the next government, but also burden sharing.

The next German government should also have a clear position on the Conference on the Future of Europe in order to make the most of this format and to actively contribute to shaping the EU’s future reform agenda.

Relations with Eastern European member states have always been very much dependent on Germany’s attitude. With increasing tensions on the rule of law, there is a need to include the rest of the member states in the debate. During the Merkel years there seemed to be a free pass to rule of law violations in the EU. Today there is an opportunity to change that perception.

Last but not least, there is a historical tension between those that defend creating a ‘coalition of the willing in the EU’ and those that promote ‘not leaving anyone behind’. Germany under Merkel was primarily the latter. The new German Chancellor may be more open to alliances within the Union for progressing in key areas of integration. This, nonetheless, should be carried out in line with European solidarity. Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News