On December 15, 1991, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker arrived in Moscow amid political chaos to meet with Russian leader Boris Yeltsin, who was at the time busy wresting power from his nemesis, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. Yeltsin had recently made a shocking announcement that he and the leaders of Belarus and Ukraine were dismantling the Soviet Union. Their motive was to render Gorbachev impotent by transforming him from the head of a massive country into the president of nothing.

In the short run, it was a brilliant move, and within ten days, it had succeeded completely. Gorbachev resigned, and the Soviet Union collapsed. The long-term consequences, however, were harder to grasp.

Even before Yeltsin’s gambit, Baker had begun worrying about whether the desire of some Soviet republics to become independent might yield bloodshed. On November 19, 1991, he had asked one of Gorbachev’s advisers, Alexander Yakovlev, if Ukraine’s breaking away would prompt violent Russian resistance. Yakovlev was skeptical and responded that there were 12 million Russians in Ukraine, with “many in mixed marriages,” so “what sort of war could it be?” Baker answered simply: “A normal war.”

Now, with Yeltsin upping the ante by calling for the Soviet Union’s complete destruction, Baker had a new fear. What would happen to the vast Soviet nuclear arsenal after the collapse of centralized command and control? As he counseled his boss, President George H. W. Bush, a disintegrating empire with “30,000 nuclear weapons presents an incredible danger to the American people—and they know it and will hold us accountable if we don’t respond.”

Baker’s goal for his December 1991 journey was thus to ascertain who, after the Soviet Union’s dissolution, would retain the power to authorize a nuclear launch and how that fateful order might be delivered. Soon after arriving, he cut to the chase: Would Yeltsin tell him?

Remarkably, the Russian president did. Yeltsin’s openness to Baker was partly a gambit to win U.S. help in his struggle with Gorbachev and partly an attempt to secure financial aid. But it was also a sign that he wanted a fresh start in Moscow’s relations with the West, one characterized by openness and trust. Yeltsin and Baker soon began working in tandem to ensure that only one nuclear successor state—Russia—would ultimately emerge from the Soviet collapse.

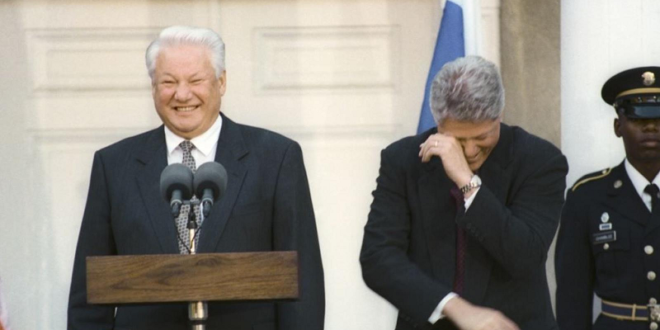

This collaboration survived Bush’s 1992 election loss. Yeltsin continued the effort with President Bill Clinton, U.S. Secretaries of Defense Les Aspin and William Perry, and Strobe Talbott, Clinton’s top Russia adviser, among others, to ensure that former Soviet atomic weapons in Belarus, Kazakhstan, and above all Ukraine were either destroyed or relocated to Russian soil. During a 1997 summit, Yeltsin even asked Clinton whether they could cease having nuclear triggers continually at hand: “What if we were to give up having to have our finger next to the button all the time?” Clinton responded, “Well, if we do the right thing in the next four years, maybe we won’t have to think as much about this problem.”

Understanding the decay in U.S.-Russian relations can help the United States manage long-term strategic competition.

By the end of the 1990s, however, that trust had largely vanished. Vladimir Putin, Yeltsin’s handpicked successor, divulged little in grudging 1999 conversations with Clinton and Talbott. Instead of sharing Russia’s launch protocols, Putin skillfully played up his perceived need for a harder Kremlin line by describing the grim consequences of reduced Russian power: in former Soviet regions, he said, terrorists now played soccer with decapitated heads of hostages.

As Putin later remarked, “By launching the sovereignty parade”—his term for the independence movements of Soviet republics in 1990–91—“Russia itself aided in the collapse of the Soviet Union,” the outcome that had opened the door to such gruesome lawlessness. In his view, Moscow should have dug in, both within the union and abroad, instead of standing aside while former Soviet bloc states jumped ship to join the West. “We would have avoided a lot of problems if the Soviets had not made such a hasty exit from Eastern Europe,” he said.

Once firmly in power, Putin began backtracking on the democratization of the Yeltsin era and on cooperative ventures with Washington. Although there were notable episodes reprising the spirit of the early 1990s—expressions of sympathy after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and a nuclear accord in 2010—the basic trend line was negative. The relationship reached frightening new lows during Russia’s 2008 conflict with Georgia and its 2014 invasion of Ukraine, and it has sunk even further since 2016, owing to the revelation of Russia’s cyberattacks on U.S. businesses, institutions, and elections.

Why did relations between Washington and Moscow deteriorate so badly? History is rarely monocausal, and the decay was the cumulative product of U.S. and Russian policies and politics over time. But it is hard to escape the fact that one particular U.S. policy added to the burdens on Russia’s fragile young democracy when it was most in need of friends: the way that Washington expanded NATO.

Expansion itself was a justifiable response to the geopolitics of the 1990s. NATO had already been enlarged a number of times. Given that former Soviet bloc states were now clamoring to join the alliance, it was neither unprecedented nor unreasonable to let them in.

Washington’s error was not to enlarge the alliance but to do so in a way that maximized Moscow’s aggravation.

What was unwise was expanding the alliance in a way that took little account of the geopolitical reality. The closer NATO moved its infrastructure—foreign bases, troops, and, above all, nuclear weapons—to Moscow, the higher the political cost to the newly cooperative relationship with Russia. Some U.S. policymakers understood this problem at the time and proposed expanding in contingent phases to minimize the damage. That promising alternative mode of enlargement would have avoided drawing a new line across Europe, but it faced strong opposition within Washington.

Instead, advocates of a one-size-fits-all manner of expansion triumphed. Washington’s error was not to enlarge the alliance but to do so in a way that maximized Moscow’s aggravation and gave fuel to Russian reactionaries. In 2014, Putin justified his takeover of Crimea as a necessary response to NATO’s “deployment of military infrastructure at our borders.”

Cold wars are not short-lived affairs, so thaws are precious. Neither country made the best possible use of the thaw in the 1990s. Today, as the United States and Russia spar over sanctions, cyberwarfare, and much else, the choices made three decades ago carry enduring significance. The two countries still possess more than 90 percent of the world’s nuclear warheads and thus the ability to kill nearly every living creature on earth. Yet between them, both states have shredded nearly every remaining arms control accord, and they have shown little willingness to replace them with new agreements.

Understanding the decay in U.S.-Russian relations—and how the manner of NATO expansion contributed to it—can help the United States better manage long-term strategic competition in the future. As the 1990s showed, the way that Washington competes can, over time, have just as profound an impact as the competition itself.

WHAT WENT WRONG?

To grasp what went wrong in U.S.-Russian relations, it is necessary to look beyond the familiar binary that categorizes NATO enlargement as either good or bad and instead focus on the manner in which the alliance grew. After the collapse of Soviet power in Europe—and in response to urgent requests from states emerging from Moscow’s domination, now justifiably eager to choose a security alliance for themselves—NATO swelled in multiple rounds of enlargement to 30 states, which together were home to nearly one billion people.

New historical evidence shows that U.S. leaders were so focused on enlarging NATO in their preferred manner that they did not sufficiently consider the perils of the path they were taking or how their choices would magnify Russia’s own self-harming choices. Put simply, expansion was a reasonable policy; the problem was how it happened.

Although NATO is an alliance of many countries, it is ultimately the United States’ views that matter most when the Article 5 guarantee—the pledge to treat an attack on one as “an attack against them all”—is at stake. Hence, a U.S.-centric, one-size-fits-all approach prevailed, despite the concerns of other members about a crucial geographic problem: the closer the alliance’s borders moved to Russia, the greater the risk that NATO expansion would derail the newfound cooperation with Moscow and endanger the dramatic progress being made on arms control.

Expansion was a reasonable policy; the problem was how it happened.

Scandinavian alliance members, such as Norway, savvy about living in a neighborhood that was Soviet-adjacent but not Soviet-controlled, had in earlier decades wisely customized their NATO memberships. As the only original NATO member sharing a border with the Soviet Union, Norway had decided against either the stationing of foreign bases or the deployment of foreign forces on its territory in peacetime and had ruled out nuclear weapons either on its land or in its ports. All of this was done to keep long-term frictions with Moscow manageable. That approach could have been a model for central and eastern European states and the Baltics, since they, too, occupy a region close to but not controlled by Russia. Some policymakers understood this dynamic at the time and supported the creation of a framework under which new allies might gain contingent memberships in phases through the so-called Partnership for Peace (PfP), an organization launched in 1994 to allow non-NATO European and post-Soviet states to affiliate themselves with the alliance.

But American hubris, combined with tragic decisions by Yeltsin—most notably, to shed the blood of his opponents in Moscow in 1993 and in Chechnya in 1994—provided ammunition to those arguing that Washington did not need phased enlargement to manage Russia. Instead, they maintained, the United States needed to pursue the policy of containment beyond the Cold War.

By the mid-1990s, “not one inch”—a phrase originally intended to signal that NATO’s jurisdiction would not move one inch eastward—had gained the opposite meaning: that no territory should be off-limits to full-membership enlargement and that there should be no binding limitations on infrastructure of any sort. And this happened just as Yeltsin was succumbing to illness and Putin was rising through the ranks in Russia. But U.S. leaders persisted, despite knowing, as Talbott put it in an internal U.S. memo on the alliance’s role in quelling violence in Bosnia, that “the big babies in Moscow,” although “a real head case,” had immense “capacity for doing harm.”

CROSSING THE LINE

Understanding the collapse in U.S.-Russian relations requires returning to a time when things were going right: the 1990s. The devil, in this case, really is in the details—specifically, in three choices that Washington made about NATO expansion, one under Bush and two under Clinton, each of which cumulatively foreclosed other options for European security.

The first choice came early. By November 24, 1989, just two weeks after the Berlin Wall’s unexpected fall, Bush was already sensing the magnitude of more changes yet to come. As protesters toppled one government after another in central and eastern Europe, it seemed clear to him that new leaders in that region would abandon the Warsaw Pact, the involuntary military alliance with the Soviet Union. But what then?

According to U.S. records, Bush put the issue to the British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher: “What if [the] East European countries want to leave [the] Warsaw Pact. NATO must stay.” Thatcher replied with her startling preferred option: she was in favor of “keeping . . . the Warsaw Pact.” According to British records, she saw the pact as an essential “fig leaf for Gorbachev” amid the humiliation of the Soviet collapse. She also “discouraged [Bush] from coming out publicly at this stage in support of independence for the Baltic Republics,” since now was not the time to question European borders.

Bush, however, was unconvinced. He “expressed concern about seeming to consign Eastern Europe indefinitely to membership of the Warsaw Pact.” The West “could not assign countries to stay” in that pact “against their will.” Bush preferred to solve this problem by pushing NATO beyond the old Cold War line.

The West German foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, subsequently proposed another option: combine NATO and the Warsaw Pact into a “composite of common, collective security,” within which the two alliances “could both finally dissipate.” Former dissidents in central Europe went even further, suggesting the most far-reaching option: their region’s complete demilitarization.

All these options were anathema to Bush, who most certainly did not want NATO to dissipate or the United States’ leading role in European security to disappear with it. In 1990, however, Gorbachev still had leverage. Thanks to the Soviet victory over the Nazis in World War II, Moscow had hundreds of thousands of troops in East Germany and the legal right to keep them there. Germany couldn’t reunify without Gorbachev’s permission. And the Soviet leader had another source of power: public opinion.

As the Cold War’s frontline, a divided Germany had the highest concentration of nuclear arms per square mile anywhere on the planet. The weapons in West Germany had been installed to deter a Soviet invasion, given how difficult it would have been for NATO’s conventional forces alone to stop a massive advance. Had deterrence failed, the missiles’ use would have rendered the heart of Europe uninhabitable—a terrifying prospect to Germans, who, because they were living at ground zero, arguably had more skin in the game than their NATO allies.

Hence, if Gorbachev had asked the Germans to trade those nuclear weapons for Soviet permission to reunify, a sizable number would have gladly agreed. Even better for Moscow, 1990 was an election year in West Germany. The chancellor, Helmut Kohl, had to be particularly attuned to voter sentiment on reunification and the nuclear issue. As Baker’s top aide, Robert Zoellick, put it at the time, if Kohl decided to signal a willingness to pay Moscow’s price, whatever that was, in advance of the election and “the Germans work[ed] out unification with the Soviets,” NATO would get “dumped.” This reality gave Moscow the ability to undermine the established order of transatlantic relations.

There were speculative discussions between the U.S. State Department and the West Germans on February 2, 1990, about how best to proceed in this delicate moment and what NATO might do beyond the Cold War line, such as “extend[ing] its territorial coverage to . . . eastern Europe.” Genscher raised this idea in a negative sense, meaning he was certain that Moscow would not allow reunification unless such coverage was explicitly ruled out. But Bush and his National Security Council sensed that they might be able to finesse the way NATO moved eastward, namely by restricting what could happen on eastern German territory after Germany joined the alliance. Although they did not use the term, they were following the Scandinavian strategy.

Reckoning with the collapse in U.S.-Russian relations requires returning to a time when things were going right.

But a week later, Baker—out of the loop with evolving White House thinking because of his extended travels—unwittingly overstepped his bounds by offering Gorbachev a now infamous hypothetical bargain that echoed Genscher’s thinking, not Bush’s: What if Gorbachev allowed reunification to proceed and Washington agreed “that NATO’s jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward from its present position?”

The secretary soon had to drop this wording, however, after realizing that it was inconsistent with Bush’s preferences. Within a couple of weeks, Baker was having to advise allies quietly that his use of “the term NATO ‘jurisdiction’ was creating some confusion” and “should probably be avoided in the future.” It was a sign that NATO would shift eastward after all, with a special status for eastern Germany, which ultimately would become Europe’s only guaranteed nuclear-free zone.

Through this move to limit NATO infrastructure in eastern Germany, and by playing on Moscow’s economic weakness, Bush shifted Gorbachev’s attention away from the removal of nuclear weapons in the western territory and toward economic inducements to allow for German reunification. In exchange for billions of deutsche marks in various forms of support, the Soviet leader ultimately allowed Germany to reunify and its eastern regions to join NATO on October 3, 1990, thus permitting the alliance to expand across the old Cold War frontline.

By October 11, 1991, Bush could even indulge in speculation about a more ambitious goal. He asked Manfred Wörner, then NATO’s secretary-general, whether the alliance’s efforts to establish a liaison organization for central and eastern European states might also “include the Baltics.” Wörner’s feelings were clear, and Bush did not contradict him. “Yes,” Wörner said, “if the Baltics apply they should be welcomed.”

NO SECOND-TIER GUARANTEES

By December 1991, the Soviet Union was gone. Soon, Bush would be gone as well, after he lost to Clinton in the 1992 U.S. presidential election. By the time the new president got his team in place, in mid-1993, hyperinflation and corruption were already weakening the prospects of democracy in Russia. Worse, Yeltsin soon made a series of tragic decisions that cast doubt on the country’s ability to develop into a peaceful, democratic neighbor to the new states on its borders.

In October 1993, clashing with anti-reform extremists in the parliament, Yeltsin had tanks fire on the parliamentary building. The fighting killed an estimated 145 people and wounded 800 more. Despite, or perhaps because of, the attack, extremists did well in the subsequent parliamentary elections, on December 12, 1993. The party that won the most votes was the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, which was “neither liberal nor democratic, but by all appearances fascist,” as the historian Sergey Radchenko has put it.

For a while, a budding friendship between “Bill and Boris” distracted the world from these troubling events. The two leaders developed the closest relationship ever to exist between an American president and a Russian leader, with Clinton visiting Moscow more times than any U.S. president before or since.

But Clinton also wanted to respond to demands from central and eastern European countries seeking to join NATO. In January 1994, he launched a novel plan for European security, one aimed at putting those countries on the path to NATO membership without antagonizing Russia. This was PfP, an idea largely conceived of by General John Shalikashvili, the Polish-born chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and his advisers. It resembled the Scandinavian strategy—but writ large.

The world created in the 1990s never fulfilled the hopes that arose after the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union.

PfP’s connection to NATO membership was intentionally left vague, but the idea was roughly that would-be NATO members could, through military-to-military contacts, training, and operations, put themselves on a path to full membership and the Article 5 guarantee. This strategy offered a compromise sufficiently acceptable to key players—even Poland, which wanted full membership and did not like the idea of having to spend time in the waiting room, but understood that it had to follow Washington’s lead.

PfP also had the benefit of not immediately redrawing a line across Europe between states with Article 5 protection and those without. Instead, a host of countries in disparate locations could join the partnership and then progress at their own pace. This meant that PfP could incorporate post-Soviet states—including, crucially, Ukraine—even if they were unlikely to become NATO allies. As Clinton put it to the visiting German chancellor, Kohl, on January 31, 1994: “Ukraine is the linchpin of the whole idea.” The president added that it would be catastrophic “if Ukraine collapses, because of Russian influence or because of militant nationalists within Ukraine.” Clinton continued: “One reason why all the former Warsaw Pact states were willing to support [PfP] was because they understood” that it could provide space for Ukraine in a way that NATO could not.

The genius of PfP was that it balanced these competing interests and even opened its door to Russia as well, which would eventually join the partnership. Clinton later noted to NATO Secretary-General Javier Solana that PfP “has proven to be a bigger deal than we had expected—with more countries, and more substantive cooperation. It has grown into something significant in its own right.”

Opponents of PfP within the Clinton administration complained that by making central and eastern European countries wait to gain the full Article 5 guarantee, the partnership gave Moscow a de facto veto over when, where, and how NATO would expand. They argued instead for extending the alliance as soon as possible to deserving new democracies. And in late 1994, Yeltsin gave PfP critics ammunition by approving what he reportedly thought would be a high-precision police action to counter separatists in the Chechnya region. Instead, he started what became a brutal, protracted, and bloody conflict.

Central and eastern European states seized on the bloodshed to argue that they might be next if Washington and NATO did not protect them with Article 5. A new term arose internally in the Clinton administration: “neo-containment.” Such thinking, along with the relationships that Polish President Lech Walesa and Czech President Vaclav Havel established with Clinton, increasingly made an impact on the American president.

So, too, did domestic political pressures. In the November 1994 U.S. midterm elections, the Republican Party took the Senate and the House. Voters had endorsed NATO enlargement as part of the Republicans’ winning platform, the “Contract with America.” Clinton wanted to win a second term in 1996, and the midterm results factored into his decision to abandon the option of expanding NATO through an individualized, gradual process involving PfP. He shifted instead to a one-size-fits-all enlargement with full guarantees from the start. Reflecting this strategy, NATO issued a public communiqué in December 1994 stating outright: “We expect and would welcome NATO enlargement that would reach to democratic states to our East.” Yeltsin, conscious of these words’ significance, was enraged.

Privately, the State Department sent the U.S. Mission to NATO a text “which the U.S. believes should emerge from the alliance’s internal deliberations on enlargement.” The text declared that “security must be equal for all allies” and that “there will be no second-tier security guarantees”—shorthand for contingent memberships or infrastructure limits. With that, although it continued to exist, PfP was marginalized.

Clinton’s shift almost caused his secretary of defense to resign. In Perry’s view, the progress on arms control in the early 1990s had been nothing short of astounding. A nuclear superpower had fallen apart, and only one nuclear-armed country had emerged from its ruins. Other post-Soviet successor states were joining the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. No weapons had detonated. There were new agreements on safeguards and transparency about the number and location of warheads. These were matters of existential importance, on which the United States and Russia had made historic progress, and now PfP’s opponents were, in his view, throwing a spanner into the works by pursuing a form of NATO expansion that Moscow would find far more threatening.

Perry held on but later regretted that he “didn’t fight more effectively for the delay of the NATO decision.” As he wrote in 2015, “The descent down the slippery slope began, I believe, with the premature NATO expansion,” and the “downsides of early NATO membership for Eastern European nations were even worse than I had feared.” As an unfortunate corollary, the Russians immediately concluded that PfP had been a ruse, even though it had not.

COST PER INCH

The significance of Clinton’s shift would become apparent over time. On his first European trip as president, in January 1994, Clinton had asked NATO leaders, “Why should we now draw a new line through Europe just a little further east?” That would leave a “democratic Ukraine” sitting on the wrong side. The partnership was the best answer, because it opened a door but also gave the United States and its NATO allies “the time to reach out to Russia and to these other nations of the former Soviet Union, which have been almost ignored through this entire debate.” Once PfP was abandoned, a new dividing line became inevitable.

Having jettisoned PfP’s method of allowing a wide array of countries to join as loose affiliates, the Clinton administration now needed to decide how many countries to add as full NATO members. The math seemed simple: the more countries, the greater the damage to relations with Russia. But that deceptively simple calculation hid a deeper complication. Given Moscow’s sensitivities, expansion to former Soviet republics, such as the Baltics and Ukraine, or to countries with particular features, such as bases that hosted foreign forces and nuclear weapons, would yield a much higher cost per inch.

This raised two questions: To decrease the cost per inch, should full-membership enlargement avoid moving beyond what Moscow considered to be a sensitive line, namely the former border of the Soviet Union? And should new members have any binding restrictions on what could happen on their territory, echoing the Scandinavian accommodations and the East German nuclear prohibition?

To both questions, the Clinton team’s answer was a hard no. As early as June 1995, Talbott had already begun pointedly telling Baltic leaders that the first countries to enter NATO as new members would certainly not be the last. By June 1997, he could be blunter. The Clinton administration “will not regard the process of NATO enlargement as finished or successful unless or until the aspirations of the Baltic states have been fulfilled.” He was so consistent in this view that his staff christened it “the Talbott principle.” The manner of enlargement was set: it should proceed without regard for the cost per inch—the opposite of the Scandinavian strategy.

Confrontation between the West and Russia has once again become the order of the day.

In April 1999, at NATO’s 50th anniversary summit in Washington, D.C., the alliance publicly welcomed the interest of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (along with six more countries) in full membership. The United States could insist, correctly, that it had never recognized the Soviet Union’s 1940 occupation of the Baltics. But that did not change the significance of the move: full-membership expansion would not stop at the former Soviet border. Washington brushed aside quiet expressions of concern from Scandinavian leaders, who noted the desirability of sticking with more contingent solutions for their neighborhood.

Coming on top of the alliance’s March 1999 military intervention in Kosovo—which Russia fiercely opposed—this turned 1999 into an inflection point for U.S.-Russian relations. Moscow’s decision to again escalate the brutal combat in Chechnya later that year added to the sense that the post–Cold War moment of cooperation was collapsing. An ailing Yeltsin reacted with bitterness to U.S. criticism of the renewed violence in Chechnya, complaining to journalists that “Clinton permitted himself to put pressure on Russia” because he had forgotten “for a minute, for a second, for half a minute, forgotten that Russia has a full arsenal of nuclear weapons.” And in Istanbul on November 19, 1999, on the margin of an Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe summit, Yeltsin’s verbal attacks on Clinton were so extreme that Talbott, as he recalled in his memoirs, decided that Yeltsin had become “unhinged.” According to the U.S. transcript of a brief private conversation between Clinton and Yeltsin, the Russian leader made sweeping demands. “Just give Europe to Russia,” Yeltsin said, because “the U.S. is not in Europe. Europe should be the business of Europeans.”

Clinton tried to deflect the tirade, but Yeltsin kept pressing, adding, “Give Europe to itself. Europe never felt as close to Russia as it does now.” Clinton replied, “I don’t think the Europeans would like this very much.” Abruptly, Yeltsin stood up and announced, “Bill, the meeting is up. . . . This meeting has gone on too long.” Clinton would not let his Russian counterpart go, however, without asking who would win the upcoming Russian election in 2000. A departing Yeltsin replied curtly, “Putin, of course.”

The two presidents had patched up relations after spats before, but now Clinton was out of time. The meeting in Istanbul would be his last with Yeltsin as president. Returning home to Moscow, Yeltsin decided to exit the political scene. Serious heart disease, alcoholism, and fear of prosecution had worn the Russian president down.

Pundits should think twice about writing off NATO.

Yeltsin had already decided that Putin was his preferred successor, because he believed that the younger man would, in the words of the Russia expert Stephen Kotkin, protect his interests, “and maybe those of Russia as well.” On December 14, 1999, according to his memoirs, Yeltsin confided to Putin that, on the last day of the year, he would make the younger man acting president.

As promised, on New Year’s Eve, Yeltsin shocked his nation with the broadcast of a brief, prerecorded resignation speech. The president’s stiff, weak delivery of his scripted words intensified the atmosphere of melancholy. Seated against the backdrop of an indifferently decorated Christmas tree, he asked Russians for “forgiveness.” He apologized, saying that “many of our shared dreams didn’t come true” and that “what we thought would be easy turned out to be painfully difficult.” Putin would subsequently uphold his end of the bargain by, in one of his first official acts, granting Yeltsin immunity.

Yeltsin left the Kremlin around 1 PM Moscow time, feeling immensely relieved to have no obligations for the first time in decades, and told his driver to take him to his family. En route, his limousine’s phone rang. It was the president of the United States. Yeltsin told Clinton to call back at 5 PM, even though the American president was preparing to host hundreds of guests at the White House that day for a lavish millennial celebration.

Meanwhile, the new leader of Russia made Clinton wait a further 26 hours before making contact. On January 1, 2000, Putin finally found nine minutes for a call. Clinton tried to put a good face on the abrupt transition, saying, “I think you are off to a very good start.”

DASHED HOPES

It soon became apparent that Putin’s rise, in terms of Moscow’s relations with Washington, was more an end than a start. The peak of U.S.-Russian cooperation was now in the past, not least as measured in arms control. Letting a decades-long trend lapse, Washington and Moscow failed to conclude any major new accords in the Clinton era.

Instead, nuclear targeting of U.S. and European cities resumed under a Russian leader who, in December 1999, had started a reign that would be measured in decades. For U.S. relations with Russia, these events signaled, if not a return to Cold War conditions precluding all cooperation, then certainly the onset of a killing frost.

Of course, for central and eastern Europeans who had suffered decades of brutality, war, and suppression, entering NATO on the cusp of the twenty-first century was the fulfillment of a dream of partnership with the West. Yet the sense of celebration was muted. As U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright remarked, “A decade earlier, when the Berlin Wall had come down, there was dancing in the streets. Now the euphoria was gone.”

The world created in the 1990s never fulfilled the hopes that arose after the collapse of both the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union. Initially, there was a widespread belief that the tenets of liberal international order had succeeded and that residents of all the states between the Atlantic and the Pacific, not just the Western ones, could now cooperate within that order. But both U.S. and Russian leaders repeatedly made choices at odds with their stated intentions to promote that outcome. Bush talked about a Europe whole, free, and at peace; Clinton repeatedly proclaimed his wish to avoid drawing a line. Yet both ultimately helped create a new dividing line across post–Cold War Europe. Gorbachev sought to save the Soviet Union; Yeltsin sought lasting democratization for Russia. Neither one succeeded.

NATO expansion was not the sole source of these problems. But the manner of the alliance’s enlargement—in interaction with tragic Russian choices—contributed to their extent and impact. Put differently, it is not possible to separate a serious assessment of enlargement’s role in eroding U.S.-Russian relations from how it happened. Washington’s error was not to expand the alliance but to do so in a way that maximized friction with Moscow. That error resulted from the United States misjudging both the permanence of cooperative relations with Moscow and the extent of Putin’s willingness to damage those relations.

The all-or-nothing expansion strategy also incurred those costs without locking in democratization. Former Warsaw Pact states succeeded in joining NATO (and eventually the European Union), only to find that membership did not automatically guarantee their democratic transformations. Subsequent research has shown that the prospect of incrementally gaining membership in international organizations—the process offered by PfP—would likely have more effectively solidified political and institutional reforms.

Even as strong a supporter of NATO enlargement as Joe Biden, then a U.S. senator, sensed in the 1990s that the way the alliance was enlarging would cause problems. As he put it in 1997, “Continuing the Partnership for Peace, which turned out to be much more robust and much more successful than I think anyone thought it would be at the outset, may arguably have been a better way to go.”

FOCUS ON THE HOW

What should Washington learn from this history? One of the biggest contemporary challenges for the United States is the way that confrontation between the West and Russia has once again become the order of the day. During Donald Trump’s divisive presidency, Democrats and Republicans agreed on little, but at least some segment of the GOP was never comfortable with Trump’s embrace of Putin. A shared sense of mission in dealing with Moscow offers a path toward a rare U.S. domestic consensus—one that leads back to NATO, still standing despite Trump’s toying with the idea of a U.S. withdrawal.

Even with Trump gone, however, critics continue to question the alliance’s worth. Some, such as the historian Stephen Wertheim, do so in general terms, arguing that Washington should no longer “continue to fetishize military alliances” as if they were sacred obligations. Other critics have more specific complaints, particularly regarding the recent chaotic withdrawal of Western forces from Afghanistan. Even Armin Laschet, at the time the candidate for German chancellor from the right-of-center Christian Democratic Union (a party normally strongly supportive of the Atlantic alliance), condemned the withdrawal as “the biggest debacle that NATO has suffered since its founding.” European allies lamented what they saw as an unconscionable lack of advance consultation, which eviscerated early hopes of a new, Biden-inspired golden age for the alliance.

Pundits should think twice about writing off NATO, however, or letting the chaos in Kabul derail post-Trump attempts at repairing transatlantic relations. European concerns are valid, and there is clearly a need for a vigorous debate over what went wrong in Afghanistan. But critics need to think about how a call to downgrade or dismantle the alliance will land in a time of turmoil. The Trump years, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Biden’s Afghan pullout have all damaged the structure of transatlantic relations. When a house is on fire, it is not time to start renovations—no matter how badly they were needed before the fire started.

There is also a larger takeaway from this history of NATO expansion, one relevant not just to U.S. relations with Russia but also to ties with China and other competitors. A flawed execution, both in terms of timing and in terms of process, can undermine even a reasonable strategy—as the withdrawal from Afghanistan has shown. Even worse, mistakes can yield cumulative damage and scar tissue when a strategy’s implementation is measured in years rather than months. Success in long-term strategic competition requires getting the details right.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News