The recent summit of Turkic-speaking states has fueled Ankara’s ambitions to lead a Turkic regional economic and security complex, but major geopolitical, economic and institutional hurdles remain.

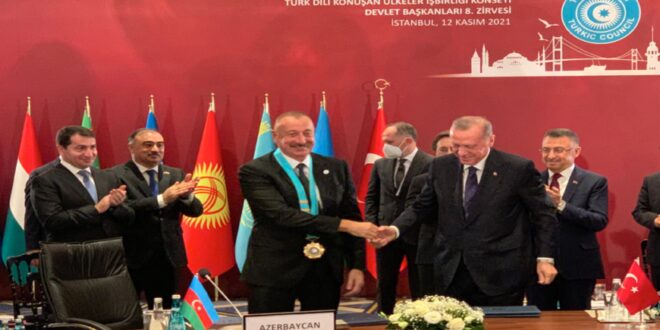

The eighth summit of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States, known as the Turkic Council, held in Istanbul last week was a critical juncture in institutionalizing the body and fit perfectly with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s domestic political agenda of consolidating his super-presidency.

The Nov. 12 summit, hosted by Erdogan, was attended by the presidents of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, which are full members of the organization along with Turkey, as well as Turkmenistan’s president and Hungary’s prime minister, whose countries hold observer status at the body. The list of participants shows clearly that the organization is a club of authoritarian and populist leaders whose agenda is largely detached from issues such as democratic advancement, human rights and the rule of law.

The meeting focused on boosting cooperation within the organization and in the fields of energy, infrastructure and transport as well as the situation in Afghanistan and other regional and international developments.

The Turkic world represents an area of 4.5 million square kilometers (1.7 million square miles) with a population of more than 160 million and a combined gross domestic product of over $1.5 trillion. Erdogan and his counterparts are well aware of the potential of the group and appear keen on creating a nonaligned strongman brotherhood in which they would back each other up.

The platform provides the leaders with an opportunity to use their partnership for political consumption at home as well as to gain some independence from the great power struggle of global heavyweights such as the United States, Europe, Russia and China and build a regional economic, diplomatic and security complex.

The participants adopted a document called “Turkic World Vision – 2040,” which sets attainable and results-oriented targets on foreign policy, security, economic cooperation, intercommunal ties and relations with foreign actors until 2040. Commenting on the document, Erdogan emphasized that member states would step up efforts to develop multilateral cooperation on global issues.

The Turkic Council was founded in 2009 by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, drawing on common ethnic and linguistic heritage. Uzbekistan joined as a full member in 2019, a year after Hungary received observer status. Turkmenistan, which follows a policy of permanent neutrality, joined the organization as an observer at the Istanbul summit.

The Turkic Council’s main decision-making body is the Council of Heads of States, which is chaired by a member state on a rotational basis. Azerbaijan is the current chair. A secretariat based in Istanbul coordinates the activities of the body.

The Turkic Council functions also as an umbrella organization for other cooperation platforms between Turkic communities such as the International Organization of Turkic Culture, the Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic Speaking Countries, the International Turkic Academy, the Turkic Culture and Heritage Foundation, and the Turkic Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

The member states plan to establish also an investment fund to back efforts to diversify their economies, increase intra-regional trade, support small- and medium-sized enterprises, and strengthen the institutional framework of the Turkic Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Efforts are underway also to improve transport links between member states, including an initiative to boost cooperation between their seaport authorities, across the so-called Trans-Caspian East-West Middle Transport Corridor from Turkey to China, which is more economical and faster than alternative trade routes between Europe and Asia.

At the summit, both Erdogan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev emphasized the importance of the so-called Zangezur corridor, a transport route that Baku aspires to receive across Armenian territory to connect mainland Azerbaijan with its autonomous exclave of Nakhchivan. For Turkey, such a route would mean not only a land link with Azerbaijan but also a gateway to the Caspian basin and Central Asia. Ankara sees significant economic potential in the route as a key link in prospective transport, communication and infrastructure projects that would bring together the Turkic world and bolster the Trans-Caspian East-West Middle Transport Corridor.

Armenia pledged to provide a transport link between Azerbaijan proper and Nakhchivan as part of the Russian-brokered armistice that ended the Azerbaijani-Armenian war over the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh in November 2020. Turkey helped Azerbaijan prevail in the war, reinforcing its influence in Azerbaijan and thus facilitating its opening to Central Asia.

Erdogan’s government now wants to advance its gains by forging closer economic and military ties with the Turkic republics in Central Asia. For Erdogan, the Turkic Council stands out as a tool to bolster Turkish presence in Eurasia amid his frayed ties with Europe and the United States and lingering concerns that he is taking Turkey away from the Western bloc.

In terms of domestic politics, the summit was an opportunity for Erdogan to cast himself as a leader of international caliber or “the leader of the Turkic world” and rally his nationalist and conservative base.

Yet, an important point to be underlined here is that none of Turkey’s partners in the Turkic Council has recognized the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) despite Ankara’s long-standing efforts to break the international isolation of the statelet, which is recognized only by Turkey. In a sign that this is bothering Ankara, Erdogan issued a fresh appeal to his counterparts at the summit. “I count on your valuable support in easing the isolation and embargo to which the Turkish Cypriots, who are an inseparable part of the Turkic world, are being subjected,” he said.

Turkey’s ultranationalists may tout the summit as a step toward the creation of a “Turkic Union,” but the lack of political support for the Turkish Cypriots shows that the Turkic Council rests largely on an economy-focused pragmatism rather than ethnic idealism.

According to a Turkish bureaucrat familiar with the body, global dynamics require Turkic states to further institutionalize their partnership. “The Turkic Council emerged on the basis of common culture and the prospect of a common future. By institutionalizing the Turkic Council, the Turkic states could attain the potential to realize common interests,” he told Al-Monitor. “Also, the upcoming period could be overcome only by the joining of forces between nations that have achieved cultural, economic and, to some extent, political cohesion. Thus, the changes and transformation trends in the shadow of global rivalries require a synergetic interaction on various levels between the Turkic states, horizontal interaction on a societal level and a facilitating institutionalization, while preserving their identities as states,” he said.

Yet, the region where the Turkic Council would flourish is seen as the backyard of Russia and China. A higher level of Turkic consciousness and closer cooperation in economic, transport and infrastructure projects would be certainly seen as a risk by Russia and China. According to Ankara’s strategic thinking, Russia and China want to retain control over Central Asia and are averse to the emergence of another powerhouse in the region.

The institutionalization of the Turkic Council is not aimed at challenging Russia and China, according to member states, but the two big powers are unlikely to be convinced. At a time when the United States and the European Union treat Russia and China as rivals, Erdogan’s government could see the process of institutionalizing the Turkic Council as a trump card in its efforts for a transactional relationship with the Joe Biden administration, promising the prospect of counterbalancing Russia and China in the region.

The issue is also of domestic significance for Erdogan, who is struggling to boost popular support for his super-presidency amid deepening economic woes since he assumed sweeping executive powers in 2018. In this context, pan-Turkist and Turkic nationalist themes might bring him more political dividends than his religious narratives, which are unwelcome in large sections of Turkish society. Similarly, the notion of Turkey being the driving force of the Turkic world could be a useful tool in forging a monolithic rightist front on the domestic political scene.

Still, the Turkic states’ reluctance to recognize the TRNC remains the most important indication of the pragmatist nature of the Turkic Council. How Moscow and Beijing react to efforts to institutionalize the body remains to be seen.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News