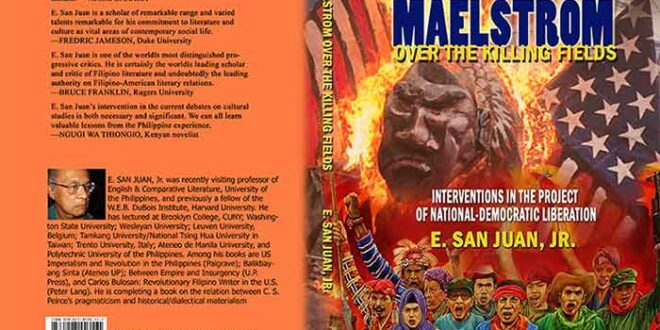

E. San Juan, Jr. is an internationally recognized cultural critic and poet in Filipino. He is emeritus professor of English, Comparative Literature, and Ethnic Studies at several US universities, and lectured recently at the University of the Philippines and Polytechnic University of the Philippines. His most recent books are Carlos Bulosan: Revolutionary Filipino Writer in the U.S. (Peter Lang), U.S. Imperialism and Revolution in the Philippines (Palgrave/Macmillan), and Maelstrom Over the Killing Fields (Pantas/Popular Book Store). This interview, a life-history as allegory of the history of a unique peripheral/unevenly developed, social formation, was conducted via Internet in November 2021.

Dr Rainer Werning is a well-known political scientist and publicist based in Cologne, Germany. He has published widely on the Philippines, Korea, and Southeast Asian affairs. He lectures with the Dept of Southeast Asian Studies, University of Bonn, and the German Society for International Cooperation. His latest book is Crown, Cross and Crusaders (Verlag Neuer Weg, Essen, Germany).

1) Where and under what conditions did you grow up? what were the most formative experiences for you during your youth?

I was born in Manila, Philippines, at the end of 1938, a month before Barcelona, Spain, fell to the Franco army aided by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Memories of the Japanese occupation (1942-45)—running to air-raid shelters during Japanese and American fighting, fleeing from Japanese brutality—gave me lessons about the horror of war. My formative years occurred in the anti-Huk/Magsaysay CIA counterinsurgency witch-hunts at the height of the Cold War. I was influenced by the secularist, progressive faculty in the University of the Philippines where I taught English literature in 1958-60. My exposure and participation in politics began with my working for the Recto-Tanada electoral campaign, as well as the partisans for academic freedom and nationalism in the University against religious obscurantism and U.S. imperial domination.

2) What prompted you to go to the USA?

Since I was already enrolled in the academic routine, the only way forward then was to earn a higher degree from a U.S. university. So I was lucky to receive a SmithMundt-Fulbright Award which enabled me to study at Harvard University in the historic period of the Civil Rights struggles (1961-65),

3) What were the most important stages of your political commitment and academic career there?

While at Harvard, I was further indoctrinated in New Critical theories with I.A. Richards, the British mentor of William Empson and other scholars. However, my other professors were orthodox, traditional philologists like Jerome Buckley, my adviser for my thesis on Oscar Wilde, and Howard Mumford Jones, the major Americanist during that period.

While finishing my graduate research, I began a correspondence with radical poet Amado V. Hernandez and other progressive artists. This led to my writing articles in Filipino (Tagalog) on William James and the Anti-Imperialist movement in the U.S. during the U.S.-Philippine War (1899-1903). When I returned to the Philippines in 1966-67, I became involved with the literary circles around Alejandro Abadilla, the avant-garde poet, and helped edit his pioneering review, Panitikan. My understanding of how subjugated the country was, and colonial dependency more subtly implnated—even before Marcos declared martial law—urged me to shift to writing mainly in Filipino and deepen my commitment to the national-liberation movement.

In the meantime, I finished by book on Carlos Bulosan published in Sept. 1972 (which narrowly escaped Marcos censorship), especially after a year of teaching (1965-66) at the University of California, Davis, where I made contact with “old-timer” Manongs for the first time and discovered the roots of the farmworkers’ radical “conscientization”(to borrow Freire’s term). Since then, the community has changed—no longer are Filipinos farmworkers, some have assimilated to middle-class domains, while the rest struggle to survive in the interstices of a decadent, really strife-torn society.

In the period 1967-1972, I was involved in party-building efforts in the United States amidst the turbulent anti-war movement and the debates within the marxist camp. We started the anti-Marcos movement among migrants, and helpted organize the Friends of the Filipino People which engaged mainly in pedagogical and lobbying efforts. Times have changed, however, so you find the majority of Filipino-Americans rallying to the white-supremacy program of Trump and his ilk. We face an uphilld battle from our beleaguered positions.

4) Where were you during the overthrow of marcos? how do you assess this event, which after all received a lot of attention worldwide?

I was still teaching at the University of Connecticut where we mobillized local agencies to expose Marcos’ systematic violation of human rights, support political prisoners, and help Filipino union activists gain solidarity from U.S. counterparts. We were constantly in touch with our comrades in MetroManila and knew how the boycott tactic boomeranged, and how the left focus on armed struggle in the countryside failed to understand the concept of counter-hegemony. In short, the old Maoist dogma of protracted war of maneuver became a sectarian principle. It acquired an obsessive force that ultimately negated the war of position—the necessary political organizing and revolutionary strategy needed to win middle forces, isolate the diehard reactionaries, and affirm intellectual-moral leadership of the national-popular front.

So the February event, while indeed a mass uprising in MetroManila, was mainly captured by the Aquino camp and led to the consolidation of oligarchic rule despite coups by disgruntled military elements. After Aquino, the Ramos presidency solidified the continuing dominance of those classes that once supported Marcos—the bloc of feudal landlords, compradors, and reactionary bureaucrat-capitalists—and the sordid surrogates behind Estrada, Arroyo, Aquino !!!, and Duterte.

Duterte himself is a Marcos wannabe but without the faux legalism of his idol—a gangster, pseudo-populist trapo schooled in warlord violence, now subsidized by Chinese agents and druglords. Lacking any genuine political program, Duterte relies on vigilante methods, bribery, threats, and manipulation of military/police personnel. But this is an opportunistic and precarious mode of rule that, despite the alibi of pandemic exigencies, will not last. Duterte’s regime is the last gasp of neocolonial political shenanigans that the U.S. started when they coopted the ilustrado class in the early twentieth century, climaxing in Quezon-Osmena hegemony, and then by U.S. puppets Roxas, Quirino, Magsaysay, Garcia, Macapagal, and Marcos. The sequence from Cory Aquino to Duterte, at the tail of the Cold War and the advent of neoliberal globalization signalled by 9/11, is now sputtering out with the really bloody, vulgarian, incoherent rule of thugs, criminals, and their hireling, all symptomatic of the decline of U.S. imperial “democracy” and the onset of a multipolar world where China has become in fantasy the new enemy of the U.S.-led coalition of morbid corporate/finance capitalism. A new world war is in the works—unless climate change and ecological disaster overtake us.

5) in 2022 the next presidential elections will be held – with Bongbong Marcos as a promising candidate – and it also marks the 50th anniversary of the imposition of martial law by his father, ferdinand e. marcos. how do you explain this rather bizarre continuity?

This is not a strange development because the 1986 February revolt did not change the class-conflicts enabling neocolonial injustice and inequality. The form of rule—from Marcos’ authoritarianism to elite/cacique demoracy—did not transform the mode of production and the associated social relations. The ideology of Marcos’ “New Society” was refurbished or retooled, while the country remained underdeveloped, lacking any viable big industry, reliant on the exploitation of natural resources.

A new element in the political economy, initiated by Marcos’ policy of labor export, began to calibrate domestic as well as transnational policies. Dollar remittances from Overseas Filipino workers—the “new heroes” celebrated by Cory Aquino—became crucial for relieving the foreign debt, and also population density, unemcployment misery, alienation, anomie, etc, But this new stratum of workers harbors a potential for anti-oligarchic mobilization, that is why the Marcos-Duterte camp is trying to control it. But with the deterioration of the economy in city and countryside, this sector might introduce an unpredictable tendency whose politics depends on subjective political agencies.

The United States has to reckon with Chinese support for Duterte, but so long as the extant mode of production remains feudal, with the rentier class tied to comprador/miitarized fractions, and the social relations pivots around clan/family dynasties, the structure is there to support versions of Marcos—whether Duterte or some other populist icon.

Meanwhile, of course, the Makabayan bloc and other progressive-nationalist forces are still around, not as strong as before, but formidable in the cultural and intellectual fields. Whether they can build enough counterhegemonic efficacy, win more activists and collective energies, remains to be seen. The future is still open—the class struggle grows sharper everyday. Sooner or later, either the people’s representatives gain ascendancy and seize power, or the whole country edges toward unrelieve misery, criminality, more suffering and deaths under the reign of violent terrorist deathsquads and warlords. It is easy to conjecture, of course, since the conflicted eality is more complex and rich, as Lenin said, so we need to continue inquiring and analyzing the balance of forces changing everyday, and try to adapt our thinking to the needs of social praxis for more effective interventiion. Enough said.

6) How would you categorize the Duterte administration in sociological terms?

Duterte inherited a structure of authoritarian rule inspired by the Marcos model of reliance on the State’s coercive agencies (Philippine National Police and Armed Forces of the Philippines). Like all State operations, it is based on the client-patron model managed by a patrimonial coalition of big landlords, comprador, and bureaucrats. We still suffer from the effects of 300 years of Spanish colonialism and over a hundred years of U.S. tutelage. The term “postcolonial” is thus a misnomer or an alibi for continuing dependency and marginality.

In 2016, there was severe dissatisfaction with Noynoy Aquino’s laid-back style of governance culminating in the Mamasapano massacre as well as the collapse of social services during periodic natural disasters. So the mood prior to Duterte’s notoriety as Davao’s action-oriented mayor was a demand for aggressive leadership.

The Marcos dynasty’s money and crony support funded the polling surveys and social media that inflated Duterte’s image as the awaited savior. His performance, misogynistic, vulgar and anti-intellectual, can only entertain but not produce substantive changes: the drug problem has considerably worsened. To aggravate nationalist sensitivity, China has claimed more territory in the West Philippine Sea despite Duterte’s inutile bravura, and acquiescence to China’s elite who will surely back his daughter’s (Sara Duterte’s) candidacy.

Contrary to the pundit’s view that Duterte is a populist leader backed by grassroots farmers and petty-bourgeois stratum, Duterte’s pseudo-charisma exploits the cinematic role of a neighborhood tough-guy who can do things quickly, ignoring customary proprieties. His campaign against drugs—the killing of more than 8,000 suspects (according to government records)—coupled with the pandemic crisis, has intensified corruption. Officials siphoned off the budget for health/medical services and anti-Covid vaccines. It has allowd the police-military to inflict abuses. After using the peace talks to uncover Communist Party networks, Duterte has resorted to red-tagging under the cover of the Anti-Terrorism Act to maintain peace and public order. The real situation is chaotic, with citizens making-do and coping with hunger, sickness, desperation all around.

Notwithstanding the arguments of Ernesto Laclau and Nicos Poulantzas, Duterte’s ascribed populism is a tawdry mimicry of Peron or any tinpot Latin-American jefe. Duterte has no wide trade-union support or ideoogical party machinery. He appeals to alienated individuals and fear-stricken middle-strata. But It has a Filipino provenance, dating back to Quezon’s “social justice” slogan to Magsaysay’s anti-Huk campaigns and recently to Marcos’ “New Society” agit-prop. Its hackneyed rhetoric glorifies Duterte’s role as protector of the masses, so its personalism bears affinities with fascist authoritarianism rathan than with Russian Narodnism of underprivileged, dislocated groups.

Neither does Duterte’s regime resemble classic Bonapartism nor Caesarism. It’s really an ad-hoc setup of mediocre, thuggish compadres to shore up the bankrupt cacique democracy we suffer under. Duterte is annoyed or challenged by the critical ethos of nationalist, progressive forces of radicalized youth, women, religious activists, immiserated peasantry, rural and urban workers, etc. It is more worried by the indignant grievances ofmiddle-strata professionals who are forced to become low-paid migrant workers whose remittances of over $12 billion a year pays off the foreign debt and enables a tiny percentage of 110 million Filipinos to indulge in luxury consumption.

7) In your opinion, what are the main weaknesses and strengths of your compatriots?

This question invokes the permanent need for historical specificity and contextualization. If you inquire closely into the vicissitudes of our anti-colonial struggles, we suffered two defeats or reversals: the suppression of the revolutionary first Philippine Republic by the U.S., and the breakdown of the Huk rebellion in the Fifties. One other defeat may be the failure of the EDSA rebellion to enact thorough land reform and eliminate political dynasties—the foremost being the Marcos one. Lessons have not yet been fully extracted from those events, given the inadequacy of our history textbooks and our amnesia-stricken national memory as a whole. We also lack fulltime organic intellectuals mediating between the middle-strata and the grassroots. We have no sustained public forums and genuinely free press to promote participatory democracy, given the terrorist government threats and rampant arrests, with hundreds of political activists jailed and tortured or extra-judicially neutralized.

In my view, we as a people have not completed the process undergone by the masses in the French Revolution, or the decades of Mao’s systematic mobilization of China’s countryside. Our neocolonial situation does not permit it. Our “enlightenment” stage was cut off by the colonial imposition of U.S. individualist-utilitarian habits which continue to commodify bodies, souls, dreams, fantasies. Underlying it is the durable mould of feudal-dependent mores, customs, and sensibility that suppresses critical reasoning and prevents any integral judgment of the totality of collective experience.

Our neocolonized belief-system has inculcated obedience and worship without questioning purpose, means, or ends. The compadrazgo mechanism functions under the umbrella of a comprador-middlemen way of conducting business that makes a mockery of the judicial-meritocratic paradigm of industrial capitalism. We are still a profoundly neocolonial formation without any heavy industry and an impoverished agricultural sector exporting cheap raw materials. Our main export now is Filipino Overseas workers, about 12 million worldwide, including Filipinos settled in North America. The market-oriented economy subsists on the hedonistic consumerism of people with relatives working abroad. Urban MetroManila, however, boasts of supporting a network of call centers and transnational corporate clearing-houses with sophisticated technological platforms required by inclusion in a neoliberal system of commerce and transnational communication.

As for strengths, they are part of our weaknesses. Our sikolohiyang Filipino experts usually cite the bayanihan and pakikisama modes of cooperation. We have some formidable trade unions and public associations engaged in scientific research and humanistic pedagogy. Nonetheless, our public sphere is dominated by clan/familial networks of damayan and pakiramdaman. Witness to this is the nationwide sympathy for Flor Contemplacion, the Filipina migrant worker hanged by the Singapore government in 1995, that panicked the Ramos regime. And earlier, the country was shocked by the killing of Senator Aquino on the airport tarmac, a distant echo of the martyrdom of the three secular priests garroted by the Spanish tyrants that catalyzed Rizal and the Propagandista movement.

Now, however, a form of inverted millenarianism has infected the academic milieu with the postmodern nihilism of Deleuze, Foucault, even Rorty and Butler, and other Western celebrities lauding the end of ideology, history, Marxism, etcetera. We are surely facing the end of Duterte’s presidency, but can the International Criminal Court and Maria Ressa’s Nobel Prize prevent the daughter from safeguarding the father’s responsibility for his crimes?

My American friends always remind me that Filipinos have one of the longest and most durable revolutionary traditions in the whole world, not just in Asia. And so I should perhaps allude here to a certain stubborn, hard-headed quality of patience learned in centuries of surviving colonial privations, and a more than Christian sense of hope that the Messiah, flying the red flag and singing the “Internationale,” will intervene at any moment now, particularly when we are plunged in the moment of danger and intolerable suffering, while Duterte’s trolls whip up the old anti-communist hysteria.

This moment of peril is the emergence (in polling surveys and social-media advertisements) of Bongbong Marcos as a favored candidate for president in the 2022 elections. An ironic twist of events? Or a bad joke by the algorithms of Twitter, Facebook and paid opinion-fabricators?

8) Why haven’t the left had a real chance of doing reasonably well in elections so far? Do they lack mass appeal and/or won’t a left-wing project – however well founded – fail because of the powerful bastion of Catholicism on the islands?

There is a problem of implementing united-front policies or principles on the part of the national-democratic camp in the arena of electoral politics. This is an old stumbling-block since the Huk rebellion in the 1950s with its adventurism and sectarian dogmatism born of the complex alignments during the Pacific War. Especially in a predominantly Catholic country, Gramsci’s dialectic of war of movement and war of position needs to be examined again and carefully adjusted to our unique social formation.

Religion or its manifestation in folk millenarianism, should not be a problem, as the theology of liberation has shown in the case of Latin America. We had a really flourishing native version of liberation theology in the seventies and eighties—until the Vatican stifled it, though Pope Francis seems to have revived it in his own unique way. But the conservative and even reactionary forms of cultish Bible-based sectarianism introducted by American evangelicals with the blessing of the CIA/Pentagon during Cory’s time to counter the National Democratic Front’s popularity may be a problem for Christians-for-National Liberation activists.

We have many progressive democratic partisans in the Church and other religious formations, including the Muslim and indigenous (Lumad) groups who have all responded productively to the appeal of Bayan Muna and national-democratic programs and objectives. A united front of diverse groups may be emerging in the wake of Duterte’s terrorism and the Marcos menace.

I think the proven success and viability of the Bayan Muna (Gabriela, AnakPawis, etc) bloc testifies to the left’s resourcefulness in electoral politics amid bribery of Barangays by traditional politicians. Money may win votes, but loyalty and political allegiance defy pecuniary distractions. By any measure, Bayan Muna’s peformance in previous electoral exercises has been a phenomenal success, despite Neri Colmenares’ failure to garner enough votes for a senate seat.

As you will recall, the People’s Party in the 1990s initiated the first attempt to test if electoral politics can be utilized to promote a national-popular agenda. This resulted in the assassination of Roberto Olalia and murderous threats on all nationalist-democratic organizations. This symptom of Cold-War hysteria still infects the whole State apparatus, from the lower courts to the Supreme Court, Senate and Batasan. This fascist mode of conducting governance can lead only to the destruction of the unstable political economy of the country and the anarchistic war of olligarchic wolves.

9) Would you agree with me that that underneath the thin surface and facade of supposedly democracy electoral processes and macropolitics in the Philippines still remain essentially feudal?

That is precisely what needs to be addressed: the mixed, conflicted modes of production that constitute the singular social formation of the Philippines in this current conjuncture. “Feudal,” of course, is a general term in the political-sociological discourse, so we need to contextualize it in Philippine history. One aspect of feudalism experienced in the Philippines is the lack of awareness of racism—the white-supremacist ideology and practice of U.S. colonialism which reinforced the Spanish/Eurocentric strategy of dividing groups according to ethnic/racial categories, and establishing hierarchies of power. The techniques of how U.S. white-supremacist ideology and practices were institutionalized among Filipinos need to be fully analyzed and evaluated, an imperative task for all Filipino activists. So we can answer why a majority of Filipinos in the U.S. support Trump’s flagrant racism and demagoguery.

Most Filipinos, both at home and abroad, have been educated/trained to identify with the white-racial code of norms, so that most Filipinos in the U.S. continue to support Trump and his unconscionable racist politics. They do not see themselves as victims of U.S. imperial domination. They are grateful for being tolerated or accepted as part of the hegemonic consensus because they see themselves as individuals, not as an oppressed group, rewarded for trying hard to adapt or adjust. The threat of anomie is warded off by identifying with Statist authority. The lack of any sense of national/racial solidarity among the victims of imperialist-colonialist subjugation may be diagnosed as a symptom of the feudal mentality, the native’s colonized ethos of subordinating herself/himself to the lord-master’s will.

I submit that no amount of analyzing Hegel’s dialectic of lord and bondsman, or scrutinizing the intricacies of the class struggle portrayed in broad strokes in the Marx/Engels canon, can remedy the Filipino habitus (if I may use Bourdieu’s term) of subalternity. We have our own counterparts to Fanon’s discourse on racialized violence and resistance in the works of Rizal, Mabini, Agoncillo, Constantino, Sison, Lumbera, and vernacular artists such as Faustino Aguilar, Ramon Muzones, Amado V. Hernandez, Lualhati Bautista, etc.. But Filipinos don’t really know these writers, nor the Rizal-Mabini genealogy of counter-hegemonic resistance. So, again, we need a new age of Enlightenment (with appropriate pedagogy) to purge the toxic legacy of feudalism and its postmodern variants—a virus worse than Covid-19—sustained by imperialist patronage and charity.

10) II you take a look into the crystal ball, what do you think the outcome of the next elections in may 2022 is most likely to be? Would you like to venture a forecast?

Cultural commentators (as the present interviewee) should refrain from forecasting the outcome of elections, so hazardous is the enterprise of gazing into the crystal ball. Prophets are often cast out from their homeland, if not crucified. However, one can speculate about trends. The trend is often manipulated, but one can discern the public’s desire for some form of reasonable, well-managed, efficient governance, especially in controlling wild skyrocketing prices of electricity, gasoline, transportation, food and other basic necessities, and helping the disabled, the unemployed, and the many victims of natural disasters.

The shameful failure of Duterte’s militarized approach to the pandemic, which brought about the mushrooming of “community pantries” red-tagged by the police and military, is sure to spark opposition to the Marcos-Duterte collusion. In other countries, such a failed regime would have resigned, shamed widely, or booted out of power.

Public figures like the mayors of Manila and Pasig are now highly acclaimed as honest, competent administrators, notwithstanding their links with traditional politicians. In this regard, the “pink” candidate Robredo is trailing behind the popularity of other candidates who are paid surrogates for shadow politicians, or just plain mediocre. In this climate of free-for-all jousting, even the boxer Paquiao has been toseed into the electoral ring. Senator Paquiao scarcely attended the Senate sessions; he has absolutely no qualification for the job except, maybe, his physical prowess and stamina—which, not to underestimate these qualities, may be what is lacking in Duterte’s debilitated and narcotic if not wholly moribund, wasted physiognomy.

So I think if money-driven propaganda and poll-surveys are discounted, I think there will be a change to another regime with personnel not completely beholden to the Marcos-Duterte collusion. In any case, Filipinos have not lost hope in a change for the better, although their choice of Duterte landed them from the frying pan into the fire, so to speak. It is time to say, “Enough! Basta!”

Indeed, how long can one endure imprisonment, torture, unwarranted arrests, extra-judicial killlings, rape, rampant abuse of authority, corruption, insult and injury to women and Lumads, and anyone who criticizes such atrocities? How long can one endure such brutal privations? How long can one suffer servitude without raising a cry of protest and vote one’s conscience (one act allowed by law) to transform the status quo into a more egalitarian and just society? There are, of course, collective means and ways other than elections to change the current situation. I expect the conscienticized citizenry in the Philippines to register their general will and elect a humane alternative to the bloody Duterte regime.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News