Qatar is enhancing its presence in the eastern Mediterranean that is rich in oil and gas reserves at a time when tensions are ripping through the region over the maritime borders and excavation rights.

Qatar has strengthened its presence in the eastern Mediterranean, which is rich in oil and gas reserves, at a time when tensions are high in the region over maritime borders and exploration rights.

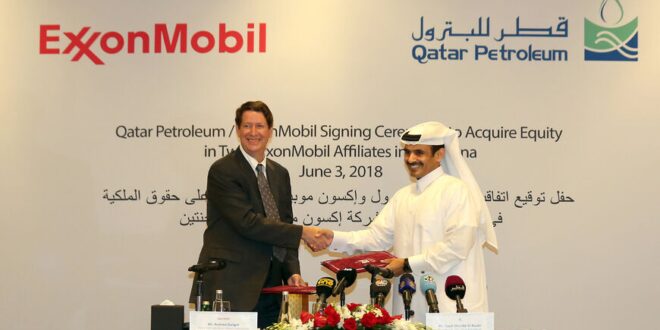

Qatar Energy, owned by the Qatari government, and the US giant ExxonMobil signed a contract Dec. 10 with Cyprus for oil and gas exploration and production sharing in Block 5 off the coast of the divided island of Cyprus.

This is Qatar’s second exploration area in Cyprus. In February 2019, Qatar Energy and ExxonMobil also announced the discovery of a huge natural gas reserve in the Glaucus field off the coast of Cyprus in Block 10, the largest discovery on the island so far containing an estimated 5-8 trillion cubic feet.

Under the new agreement with the Nicosia government, Qatar Energy will own a 40% stake in Block 5, while ExxonMobil will own a 60% stake and will be the operator in the area.

Turkey, on the one hand, and Greece and Cyprus, on the other, have been involved for years in a dispute over sovereignty claims in the eastern Mediterranean, in addition to the status of some islands in the Aegean Sea, not to mention the dispute over the ethnically divided island of Cyprus between Ankara and Athens.

Greece and Turkey, both members of NATO, do not agree on the borders of their continental shelf. When it comes to Cyprus, Turkey does not recognize the existence of a continental shelf, nor does it recognize the government of Nicosia.

Cyprus was divided after the Turkish invasion of the island in 1974 due to a military coup instigated by Greece to the north that is controlled by the Turkish Cypriots and the south controlled by the Greek Cypriots. Turkey is the only country to recognize Northern Cyprus as an independent state, and it does not have diplomatic relations with the government of Cyprus, a member of the European Union.

Turkey soon announced its rejection of the new agreement and accused Cyprus of violating its continental shelf by granting an exploration license to ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum. Turkey has threatened to ban the two companies from drilling.

However, Turkey is a strong ally of Qatar, and their relations have greatly strengthened since the Gulf crisis in June 2017, when Doha became a diplomatic pariah after Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Egypt decided to sever diplomatic ties with it and accused it of supporting and financing terrorism. They settled their differences early this year by signing an agreement in the Saudi city of Al-Ula.

Egypt, a regional rival to Turkey, has had close ties with Cyprus and Greece since Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi took power in 2014. The three countries have held several tripartite summits on energy, gas exploration, counterterrorism and border demarcation, often attacking Ankara’s policies in the eastern Mediterranean.

Andreas Krieg, a UK-based Middle East analyst, told Al-Monitor that the contract with Cyprus has been in the making for a couple of years and has now become actually feasible amid a regional climate of de-escalation.

Krieg said, “Qatar remains a fairly neutral player in the eastern Mediterranean supporting Turkish claims based on GNA-Ankara agreements, while also working with Cyprus now to get access to a potentially lucrative exploitation opportunity.”

In August 2020, Egypt and Greece signed an agreement to demarcate the maritime borders between them, which effectively nullified an agreement that Turkey had signed with the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) during its term in Tripoli in November 2019 to demarcate the maritime borders. Egypt and Greece described the deal as illegal and in violation of international law, and Greece considers it an infringement on its continental shelf, specifically off the island of Crete.

Experts who spoke to Al-Monitor believe that Qatar’s increasing influence in the eastern Mediterranean may be a starting point for broader political cooperation with Egypt, and that it will facilitate an opportunity for Doha to play the role of mediator to promote rapprochement between Turkey and Egypt.

Mohammed Soliman, scholar at the Middle East Institute, told Al-Monitor that Egypt would view positively the offshore gas exploration deal between Cyprus with Qatar Energy and ExxonMobil.

Soliman said, “The eastern Mediterranean is filled with commercial and political opportunities, and it could be another cooperation opportunity for Egypt and Qatar.”

Sisi and the emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad, met at the end of August 2021 in Baghdad for the first time since the Al-Ula agreement, which ended more than three years of estrangement between them. Egypt and Qatar appointed ambassadors in each others’ country, in an indication of improving relations.

Krieg said, “From all rapprochements between Qatar and the former blockading states, the relationship with Egypt has become the closest. Egypt and Qatar reengaged with no strings attached and without any preconditions making it easier to return to a normal working relationship.”

He noted, “Aside from close cooperation on the Palestine file, Qatar and Egypt have agreed on investments that are mutually beneficial and generate not just economic but political returns, especially in the field of energy, logistics and infrastructure.”

Despite this, it seems that Qatar’s task with regard to mediating between Egypt and Turkey is not an easy one. The two countries are rival regional powers, and relations deteriorated between them after the Egyptian army toppled former Muslim Brotherhood President Mohammed Morsi following popular protests against his rule in 2012-13. In November 2013, both Egypt and Turkey withdrew their ambassadors and froze their relations.

Since then, Cairo and Ankara have been locked in a dispute that has turned into a broader regional struggle over political Islam. The authorities in Egypt designated the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist group, while Turkey provided sanctuary to hundreds of members and leaders of the group who fled Cairo with the support of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, leader of the Islamist Justice and Development Party.

In Libya, the two countries were at odds as they backed the warring Libyan parties before electing a presidential council and national unity government in February 2020, to lead the country through a transitional period under the auspices of the United Nations, in preparation for general elections by the end of 2021.

Before that, Turkey deployed soldiers and thousands of Syrian mercenaries in Libya to help the Tripoli-based GNA repel an attack launched by eastern Libyan forces led by Khalifa Hifter with the support of Egypt, the UAE and Russia.

Egypt has repeatedly demanded the withdrawal of foreign forces and mercenaries from Libya. But Turkey says the presence of its forces in Libya is part of a military cooperation agreement signed with the GNA in the midst of a fierce civil war between eastern and western Libya.

In response, Egypt sought to isolate Turkey regionally in the conflict of alliances in the eastern Mediterranean, as Egypt, Cyprus and Greece in addition to Israel, Italy, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority formed the Cairo-based East Mediterranean Gas Forum in January 2019 as a governmental organization with commercial and political goals against Turkey as well.

Accordingly, early this year, Turkey took a more flexible approach in reformulating its regional alliances with Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE in addition to Israel as part of an attempt to build bridges of cooperation with countries allied with the United States, after years of political competition and military interventions that demonstrated Turkey’s influence in the region, but spoiled its alliances in the Arab world.

Krieg said that Qatar has an opportunity to play the role of a go-between helping with the rapprochement between Turkey and Egypt, which so far saw Ankara being more interested than Cairo in normalization.

“At the least, Qatar can help de-escalate tensions when they arise as it now has a stake in the region as well — albeit of less geostrategic importance than for other eastern Mediterranean players. But again, this could be another reason for Qatar trying to de-escalate here rather than fueling conflict,” he noted.

In early March, Egyptian and Turkish officials announced the resumption of diplomatic contacts between them. The two countries said in a joint statement Sept. 8 that they agreed to continue talks to repair and eventually normalize relations, after concluding a second round of “exploratory talks” aimed at settling differences.

Officials of the two countries have so far held two rounds of bilateral talks in May and September. But talks between the two countries have abruptly been frozen since then, and Cairo considers Ankara not serious about mending ties yet.

“The offshore gas exploration deal in Cyprus with ExxonMobil and Qatar Energy was obviously previously discussed with Turkey during Erdogan’s visit to Doha [Dec. 6]. Turkey agreed to it in the hope that Qatar can help push for a rapprochement with Egypt,” Krieg concluded.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News