Offers of money by the Islamic State to join its ranks prove “irresistible” to those hit hard by Syria’s collapsed economy.

A man being led by security guards shuffles into an interrogation cell in a military prison in the Kurdish-administered city of Hasakah in northeastern Syria. His hands are cuffed, and his head is shrouded in a black hood. He was arrested at his home in the city of Raqqa and brought here on Oct. 2 on charges of membership in the Islamic State (IS).

The guards escorting him remove the hood. He has ruddy cheeks, thick brown hair and a beard. Ahmed (a pseudonym, as prison authorities would not let him reveal his real name) sat down for an interview with Al-Monitor on a recent afternoon and described why he joined IS more than two years after the jihadis lost Baghouz — the last patch of territory in their collapsed caliphate — to the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in March 2019. “I did it for the money,” the 24-year-old father of three said. “Because of the drought, my farm collapsed. I had a lot of debts.”

Ahmed’s profile is typical, according to the Kurdish official who is in charge of running the maximum-security prison where an attempted escape by IS inmates was foiled just days after the interview. “They are paying people to join them, paying thousands of dollars,” the official, who asked not to be identified, told Al-Monitor. Some 50 jihadis being held at the prison were captured this year, the official said. All had joined for money.

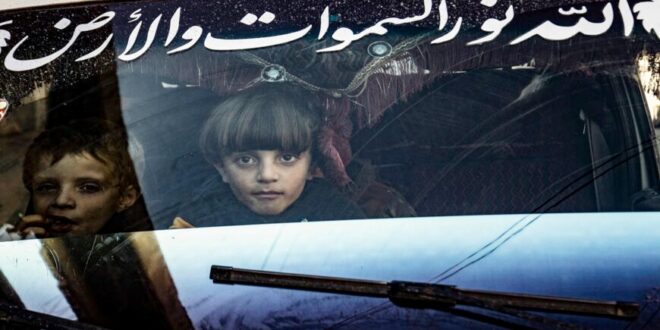

Syria has been hit by its worst drought in 70 years, and farming is one of the main sources of income in northeast Syria where most of the country’s crops are grown. Coming on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, the collapse of Syria’s national currency and international sanctions on the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, the drought has further impoverished millions of people, leading some like Ahmed to join IS in order to make ends meet. A far greater number risk their lives as they try to flee the country to Europe illegally.

Ahmed says he was approached in May 2020 by a friend who joined IS and was living in the town of al-Bab, a former IS stronghold that was overrun by Turkish forces and their Sunni rebel allies in February 2017 with US support. “There are many [IS members] living in the Turkish-occupied areas. I think most of them are there,” Ahmed said.

“My friend introduced me to a man called Salman who told me to deliver a Syrian marriage document to another [IS] member. They paid me 50,000 Syrian pounds for this job. I continued to do such jobs as a courier,” he said.

“I had nothing to do with military work,” Ahmed added. His brother needed costly medical treatment after a motorbike accident. The offer had proven irresistible.

After their crushing defeat in Iraq and Syria by the US-led coalition and its SDF allies, the jihadis and their global affiliates are seeking to regroup and have begun to mount increasingly audacious attacks in places like Afghanistan and Uganda alongside their traditional strongholds in Syria and Iraq.

“I am concerned that they will be strong again. We are trying to break up the cells. The [Arab] tribes are being very helpful. But to be honest, in regime-controlled areas especially, the Syrian [Arab] army is not performing so well against them,” the prison official said.

On Dec. 25, the SDF announced the arrest of “one of the most dangerous leaders” of IS, Muhammad Abul-Awwad, who had helped organize the attempted escape at the military prison in Hasakah. In his filmed confession, Abul-Awwad said the plan included detonating two car bombs at the gates of the prison and using 14 suicide bombers to storm it.

The SDF Press has announced the arrest of Muhammad Abdul-Awwad, "one of the most dangerous leaders" of ISIS, who among other things was responsible for the attempted Ghweiran prison break in November. The arrest occurred in coordination with the @coalition. pic.twitter.com/1jvv0QSsOr

— Rojava Information Center (@RojavaIC) December 25, 2021“We are on the ground everywhere,” boasted another Syrian Arab IS prisoner interviewed by Al-Monitor. “God willing we will have our Islamic State,” he said. “Yes, it’s true, many are joining now for money,” he acknowledged, averting his eyes from a woman reporter because “it’s against Islam to be in the same room with you.” Arrested in 2019, the prisoner said he was active in Raqqa, the jihadis’ erstwhile capital, “killing lots of enemies” but not doing any beheadings “because it takes too long.”

The US Treasury noted in a recent report that IS “probably has tens of millions of US dollars available in cash reserves that are dispersed across the region” and that it continues to move funds in and out of Syria and Iraq, “often relying on [IS] facilitators in Turkey and in other financial centers.”

The Rojava Information Center, an independent research organization in northeast Syria, observed that IS sleeper cell attacks are on the rise, especially in the Arab majority Deir ez-Zor region. Of a total of 22 attacks that were documented in November, 14 were claimed by the jihadis.

Mazlum Kobane, commander in chief of the SDF, said in a recent interview with Al-Monitor that one of the greatest threats to northeast Syria was no longer physical attacks by IS but the militants’ ability to exploit the current economic crisis to lure new recruits.

Kobane said, “These unfavorable economic conditions are impacting our struggle against [IS]. Its ability to regain ground is increasingly linked to economic conditions in Syria. There are way too many unemployed people. There is widespread poverty.”

Almost 60% of Syria’s nearly 21 million people are “food insecure,” and nearly 12 million are losing access to food, water and electricity all together as a result of the drought, according to the United Nations. Elizabeth Tsurkov, a doctoral student at Princeton University who has written extensively on Syria, told Al-Monitor, “In all areas, parents are eating less so that their children can eat enough. People have given up eating fruits and vegetables, cheese and eggs.”

The relative stability and prosperity seen in the northeast compared to the rest of Syria, owed in part to US military protection and funds, are increasingly at risk because of the drought and Ankara’s unremitting hostility, including restricting access to water for more than a million residents in al-Hasakah.

Kobane argued that the first order of business must be for the United States to exempt the northeast from crippling sanctions imposed on the Assad regime in order to clear the path for potential investors, particularly in the oil sector. But the Biden administration has not budged so far and has refused to extend a waiver granted to a US oil company under the Trump administration that had signed a deal with the Kurdish-led administration.

For Abed Mehbes, co-chair of the Executive Council of Northeast Syria (the top administrative body based in Raqqa), the idea of an IS comeback is intolerable. “When we first came here to rebuild the city, there were animals eating the dead IS bodies. Raqqa was in ruins.” The administration has since rebuilt 60% of the town’s critical infrastructure, he asserted. “Over 10,000 of our fighters sacrificed their lives for this.”

On a recent evening, young women with their heads uncovered and unaccompanied by males sat chatting in Raqqa’s Naim Square where IS used to stage its public beheadings. A man hawked giant heart-shaped balloons that said “I love you.” Restaurants serving sizzling kebabs and hot breads coated in spicy tomato paste were filled with customers of both sexes.

Mehbes insisted that the gravest danger facing the Kurdish-led autonomous enclave was Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party “who are the big friends of [IS].”

Since October, Turkey has grown more aggressive with its drone strikes targeting alleged members of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party. Turkey says the militant group, which has been fighting the Turkish army since 1984, is “the same” as the SDF, Ankara’s stock argument to justify its continued assaults.

On Christmas day, a Turkish drone struck a group of Syrian Kurdish youth activists in the border town of Kobane, killing five. The autonomous administration condemned the attack in the statement, saying, “Turkey aims to smash the will of the population and destroy efforts to strengthen democracy and achieve stability.”

Turkey has long been accused of turning a blind eye to the thousands of foreign fighters who flocked to the IS caliphate via its borders because they were fighting the Kurds. Its reluctance to let the US-led coalition use the Incirlik air base to target the jihadis — it relented in July 2015 — reinforced claims that it was colluding with them.

Thamer Jamal al-Turki, a sheikh from Al Sabkha tribe, told al-Monitor, “Turkey, the [Syrian] regime and Iran — they all want to make problems between us and the SDF.” He insisted that all three were supporting IS sleeper cells in northeast Syria so as to destabilize and weaken the Kurdish-led administration. “They are not strong like before. But they are organizing in the countryside, stealing our sheep and attacking our men,” Turki said.

The lack of opportunity and uncertainty about Syria’s future are driving ever-larger numbers of people to make their way out of Syria via Turkey and Iraq or by air from Damascus. Many get turned back, scammed by smugglers or die at sea as they try to brave choppy seas in rickety boats headed for European shores.

Others become pawns in the hands of callous political leaders seeking to blackmail Europe, as witnessed most recently in Belarus where thousands of illegal migrants, mostly Iraqi and Syrian Kurds, remain marooned in freezing temperatures in no-man’s land between the Polish and Belarussian borders. On Nov. 12, the body of a dead man was found on the Polish side. Polish officials said he was Syrian and around 20 years old. The cause of his death remains unknown.

On a recent drive between the towns of Amude and al-Darbasiyah, a Syrian Kurdish translator pointed at grayish material caught on razor wire fencing atop a concrete wall that skirts the 911-kilometer-long border.

“Look, pantaloons (men’s baggy trousers),” the translator exclaimed. Articles of clothing caught on the wire and blankets thrown over it for protection by people attempting to scale the wall are a common sight, the translator said. That day, three pairs of trousers and one blanket were flapping on the wire between Amude and al-Darbasiyah.

The wall was erected by Turkey to keep out Syrians. Turkey hosts more refugees than any country in the world, including 3.7 million Syrians, and doesn’t want any more.

“Even after the erection of the wall, irregular crossings over the Turkish border are still happening,” said Omar Kadikoy, policy analyst at the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey, an Ankara-based think tank.

A Syrian Kurdish smuggler who spoke to Al-Monitor on condition of anonymity confirmed that he was among those helping to arrange the crossings. “The wall is useless. It’s just a design,” he said.

“When the Syrian crisis began in 2012, I started my business. I used to work in a Syrian government office for $110 a month. I have 10 kids. I needed the income,” he explained.

It’s hard and sometimes heartbreaking work. “I took a group of Christians several years ago. They stepped on a mine. All of them died,” the smuggler said. “The soldiers on the [Turkish side] put them in a bulldozer and tossed them over the wall.” Al-Monitor was unable to confirm the veracity of this account. But an undocumented number of Syrians have died while attempting to cross into Turkey as Turkish border guards fired warning shots into the air.

The crossings have become far riskier since October 2019 when Turkey invaded a large slab of territory in northeastern Syria, including the towns of Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ain. “Turks are now using drones to patrol the border,” the smuggler said. These day no more than two people cross per night, he added. Corruption on both sides of the border creates loopholes for the smuggler and his friends.

The SDF has been cracking down on the human trafficking rings, arresting complicit officials and planting mines along the length of the wall. The smuggler acknowledged that he had done time and that many of his colleagues are in jail.

In 2019, a group of Syrian Kurdish emigres in Germany decided to take matters into their own hands. They raised money between themselves to launch an internet technology company that would employ bright young Syrians and keep them at home. The outfit, the first of its kind, is based in a modern and cheerful office in Amude and is called Northeast Syria Technology, or NESTECH.

The young Syrian Kurdish woman who runs the company, a law graduate fluent in four languages, introduced a reporter to her team, some in person and others virtually, on a recent morning on condition that none be identified by name. “We have to protect them from the regime,” she explained.

The Syrian government frowns upon any effort that is seen as bolstering Kurdish self-governance. Much of NESTECH’s equipment was smuggled in from Iraqi Kurdistan on the backs of donkeys. Finding spare parts is a nightmare. “But somehow we manage,” she said.

The company currently employs 35 young Syrians — not only Kurds, but also Sunni Arabs from Raqqa and Alawites who work out of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s stronghold in Latakia. “When we advertised the jobs via Facebook in 2019, we got over 600 applications from across the country,” she recalled. “We did background checks. One’s uncle turned out to be [with IS], so we asked him to leave.”

Hasan, a pseudonym, has a degree in artificial intelligence from Damascus University. In 2018, he set in motion plans to make his way to Germany via Sudan, paying a smuggler $10,000 dollars for a fake passport to get there. Then the coronavirus pandemic struck and the scheme collapsed. Hasan’s dream is to go to Silicon Valley. In the meantime, his job at NESTECH pays over $500 per month, a princely sum in Syria, where a professor earns around $50 per month.

The company has landed several contracts since April, including one to digitize the local municipalities and another to help upgrade the communications infrastructure in the US-protected region. The female manager says the company is expected to become commercially viable in the next two years. But such efforts, worthy as they are, remain a drop in the sea. A 28-year-old network engineer said, “Every day I think of leaving Syria. I think I deserve better.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News