Why Constitutional Crises and Political Violence Could Soon Be the Norm

When Joe Biden was sworn in as president a year ago today, many Americans breathed a heavy sigh of relief. President Donald Trump had tried to steal the election, but he had failed. The violent insurrection he incited on January 6, 2021, had shaken the United States’ democratic system to its core, but left it standing in the end.

One year into Biden’s presidency, however, the threat to American democracy has not receded. Although U.S. democratic institutions survived the Trump presidency, they were badly weakened. The Republican Party, moreover, has radicalized into an extremist, antidemocratic force that imperils the U.S. constitutional order. The United States isn’t headed toward Russian- or Hungarian-style autocracy, as some analysts have warned, but something else: a period of protracted regime instability, marked by repeated constitutional crises, heightened political violence, and possibly, periods of authoritarian rule.

CLOSE CALL

In 2017, we warned in Foreign Affairs that Trump posed a threat to U.S. democratic institutions. Skeptics viewed our concern for the fate of American democracy as alarmist. After all, the U.S. constitutional system had been stable for 150 years, and reams of social science research suggested that democracy was likely to endure. No democracy even remotely as rich—or as old—as the United States’ had ever broken down.

But Trump proved to be as autocratic as advertised. Following the playbook of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, and Viktor Orban in Hungary, he worked to corrupt key state agencies and subvert them for personal, partisan, and even undemocratic ends. Public officials responsible for law enforcement, intelligence, foreign policy, national defense, homeland security, election administration, and even public health were pressured to deploy the machinery of government against the president’s rivals.

Trump did more than politicize state institutions, however. He also tried to steal an election. The only president in U.S. history to refuse to accept defeat, Trump spent late 2020 and early 2021 pressuring Justice Department officials, governors, state legislators, state and local election officials, and, finally, Vice President Mike Pence, to illegally overturn the election results. When these efforts failed, he incited a mob of his supporters to march on the U.S. Capitol and try to prevent Congress from certifying Biden’s win. This two-month campaign to illegally remain in power deserves to be called by its name: a coup attempt.

As we feared, the Republican Party failed to constrain Trump. In a context of extreme political polarization, we predicted, congressional Republicans were “unlikely to follow in the footsteps of their predecessors who reined in Nixon.” Partisan loyalty and fear of primary challenges by Trump supporters outweighed constitutional commitments, undermining the effectiveness of the system’s most powerful check on presidential abuse: impeachment. Trump’s abuses exceeded Nixon’s by orders of magnitude. But only ten of 211 Republicans in the House voted to impeach Trump in the wake of the failed coup, and only seven of 50 Republicans in the Senate voted to convict him.

Trump proved to be as autocratic as advertised.

American democracy survived Trump—but barely. Trump’s autocratic behavior was blunted in part by public officials who refused to cooperate with his abuses, such as Georgia’s secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, or who refused to remain silent about them, such as Alexander Vindman, a specialist on the National Security Council. Many judges, including some appointed by Trump himself, blocked his efforts to overturn the election.

Contingent events also played a role in defeating Trump. The COVID-19 pandemic was his “Katrina moment.” Just as President George W. Bush’s mishandling of the aftermath of the 2005 hurricane eroded his popularity, Trump’s disastrous response to the pandemic may have been decisive in preventing his reelection. Even so, Trump very nearly won. A tiny shift in the vote in Georgia, Arizona, and Pennsylvania would have secured his reelection, seriously imperiling democracy.

Although American democracy survived Trump’s presidency, it was badly wounded by it. In light of Trump’s egregious abuse of power, his attempt to steal the 2020 election and block a peaceful transition, and ongoing state-level efforts to restrict access to the ballot, global democracy indexes have substantially downgraded the United States since 2016. Today, the United States’ score on Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index is on a par with Panama and Romania, and below Argentina, Lithuania, and Mongolia.

MOUNTING THREATS

Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election did not end the threat to American democracy. The Republican Party has evolved into an extremist and antidemocratic party, more like Hungary’s Fidesz than traditional center-right parties in Europe and Canada. The transformation began before Trump. During Barack Obama’s presidency, leading Republicans cast Obama and the Democrats as an existential threat and abandoned norms of restraint in favor of constitutional hardball—the use of the letter of the law to subvert the spirit of the law. Republicans pushed through a wave of state-level measures aimed at restricting access to the ballot box and, most extraordinarily, they refused to allow Obama to fill the vacancy on the Supreme Court created by Associate Justice Antonin Scalia’s death in 2016.

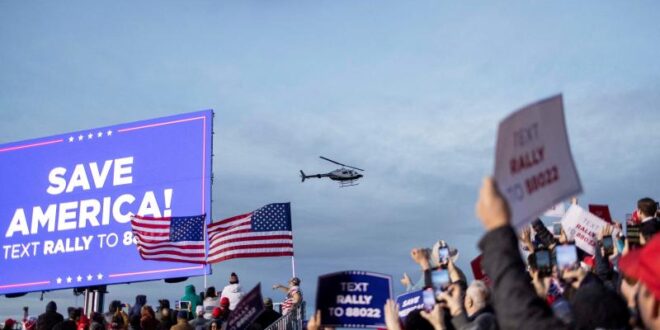

Republican radicalization accelerated under Trump, to the point where the party abandoned its commitment to democratic rules of the game. Parties that are committed to democracy must, at minimum, do two things: accept defeat and reject violence. Beginning in November 2020, the Republican Party did neither. Most Republican leaders refused to unambiguously recognize Biden’s victory, either openly embracing Trump’s “Big Lie” or enabling it through their silence. More than two-thirds of Republican members of the House of Representatives backed a lawsuit filed with the Supreme Court seeking to overturn the 2020 election, and on the evening of the January 6 insurrection, 139 of them voted against certifying the election. Leading Republicans also refused to unambiguously reject violence. Not only did Trump embrace extremist militias and incite the January 6 insurrection, but congressional Republicans later blocked efforts to create an independent commission to investigate the insurrection.

Although Trump catalyzed this authoritarian turn, Republican extremism was fueled by powerful pressure from below. The party’s core constituents are white and Christian, and live in exurbs, small towns, and rural areas. Not only are white Christians in decline as a percentage of the electorate but growing diversity and progress toward racial equality have also undermined their relative social status. According to a 2018 survey, nearly 60 percent of Republicans say they “feel like a stranger in their own country.” Many Republican voters think the country of their childhood is being taken away from them. This perceived relative loss of status has had a radicalizing effect: a 2021 survey sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute found that a stunning 56 percent of Republicans agreed that the “traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to stop it.”

The threats to American democracy are mounting.

The Republican turn toward authoritarianism has accelerated since Trump’s departure from the White House. From top to bottom, the party embraced the lie that the 2020 election was stolen, to the point that Republican voters now overwhelmingly believe it is true. In much of the country, Republican politicians who openly rejected this lie or supported an independent investigation into the January 6 insurrection have put their political careers at risk.

The newly transformed Republican Party has launched a major assault on democratic institutions at the state level, increasing the likelihood of a stolen election in the future. On the heels of Trump’s “stop the steal” campaign, his supporters have launched a campaign to replace state and local election officials who certified the 2020 election—from secretaries of state down to neighborhood precinct officers—with Trump loyalists who appear more willing to overturn a Democratic victory. Republican state legislatures across the country have also adopted measures to restrict access to the ballot box and empower statewide officials to intervene in local electoral processes—purging local voter rolls, permitting voter intimidation by thuggish observer groups, moving or reducing the number of polling sites, and potentially throwing out ballots or altering results. It is now possible that Republican legislatures in multiple battleground states will, under a loose interpretation of the 1887 Electoral Count Act, use unsubstantiated fraud claims to declare failed elections in their states and send alternate slates of Republican electors to the Electoral College, thereby contravening the popular vote. Such constitutional hardball could result in a stolen election.

The U.S. business community, historically a core Republican constituency, has done little to resist the party’s authoritarian turn. Although the U.S. Chamber of Commerce initially pledged to oppose Republicans who denied the legitimacy of the 2020 election, it later reversed course. According to The New York Times, the Chamber of Commerce, along with major corporations such as Boeing, Pfizer, General Motors, Ford Motor, AT&T, and United Parcel Service, now funds lawmakers who voted to overturn the election.

The threats to American democracy are mounting. If Trump or a like-minded Republican wins the presidency in 2024 (with or without fraud), the new administration will almost certainly politicize the federal bureaucracy and deploy the machinery of government against its rivals. Having largely purged the party leadership of politicians committed to democratic norms, the next Republican administration could easily cross the line into what we have called competitive authoritarianism—a system in which competitive elections exist but incumbent abuse of state power tilts the playing field against the opposition.

IMPEDIMENTS TO AUTOCRACY

Although the threat of democratic breakdown in the United States is real, the likelihood of a descent into stable autocracy, as has occurred, for example, in Hungary and Russia, remains low. The United States possesses several obstacles to stable authoritarianism that are not found in other backsliding cases. Take Hungary under Orban. After winning election in 2010 on an ethnonationalist platform, Orban and his party, Fidesz, packed the courts and the electoral bodies, suppressed independent media, and used gerrymandering, new campaign regulations, and other legal shenanigans to gain advantage over the opposition. Some observers have warned that Orban’s path to authoritarianism could be replicated in the United States.

But Orban was able to consolidate power because the opposition was weak, unpopular, and divided between far-right and socialist parties. Moreover, with the country having only recently emerged from totalitarian rule, Hungary’s private sector and independent media were far weaker than their American counterparts. Orban’s ability to quickly gain control of 90 percent of Hungarian media—including the largest independent daily and every regional newspaper—remains unthinkable in the United States. The path to autocracy was even smoother in Russia, where media and opposition forces were weaker than in Hungary.

Rather than autocracy, the United States appears headed toward endemic regime instability.

By contrast, an effort to consolidate autocracy in the United States would face several daunting obstacles. The first is a powerful opposition. Unlike other backsliding countries, including Hungary, India, Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela, the United States has a unified opposition in the Democratic Party. It is well-organized, well-financed, and electorally viable (it won the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections). Moreover, due to deep partisan divisions and the relatively limited appeal of white nationalism in the United States, a Republican autocrat would not enjoy the level of public support that has helped sustain elected autocrats elsewhere. To the contrary, such an autocrat would face a level of societal contestation unseen in other democratic backsliders. As Robert Kagan has argued, Republicans may seek to rig or overturn a close election in 2024, but such an effort would likely trigger enormous—and probably violent—protests across the country.

An authoritarian Republican government would also face a much stronger and more independent media, private sector, and civil society. Even the most committed American autocrat would not be able to gain control of major newspapers and television networks and effectively limit independent sources of information, as Orban and Russian President Vladimir Putin have done in their countries.

Finally, an aspiring Republican autocrat would face institutional constraints. Although it is increasingly politicized, the U.S. judiciary remains far more independent and powerful than its counterparts in other emerging autocracies. In addition, U.S. federalism and a highly decentralized system of elections administration provide a bulwark against centralized authoritarianism. Decentralized power creates opportunities for electoral malfeasance in red—and some purple—states, but it makes it more difficult to undermine the democratic process in blue states. Thus, even if the Republicans manage to steal the 2024 election, their ability to monopolize power over an extended period of time will likely be limited. America may no longer be safe for democracy, but it remains inhospitable to autocracy.

UNSTABLE FUTURE

Rather than autocracy, the United States appears headed toward endemic regime instability. Such a scenario would be marked by frequent constitutional crises, including contested or stolen elections and severe conflict between presidents and Congress (such as impeachments and executive efforts to bypass Congress), the judiciary (such as efforts to purge or pack the courts), and state governments (such as intense battles over voting rights and the administration of elections). The United States would likely shift back and forth between periods of dysfunctional democracy and periods of competitive authoritarian rule during which incumbents abuse state power, tolerate or encourage violent extremism, and tilt the electoral playing field against their rivals.

In this sense, American politics may come to resemble not Russia but its neighbor Ukraine, which has oscillated for decades between democracy and competitive authoritarianism, depending on which partisan forces controlled the executive. For the foreseeable future, U.S. presidential elections will involve not simply a choice between competing sets of policies but rather a more fundamental choice over whether the country will be democratic or authoritarian.

Finally, American politics will likely be marked by heightened political violence. Extreme polarization and intense partisan competition often generate violence, and indeed, the United States experienced a dramatic spike in far-right violence during Trump’s presidency. Although the United States probably isn’t headed for a second civil war, it could well experience a rise in assassinations, bombings, and other terrorist attacks; armed uprisings; mob attacks; and violent street confrontations—often tolerated and even incited by politicians. Such violence might resemble that which afflicted Spain in the early 1930s, Northern Ireland during the Troubles, or the American South during and after Reconstruction.

American democracy remains at risk. Although the United States probably won’t follow the path of Putin’s Russia or even Orban’s Hungary, enduring conflict between powerful authoritarian and democratic forces could bring debilitating—and violent—regime instability for years to come.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News