China may have missed the European Scramble for Africa that characterized the turn of the last century, but it has been making up for this since the 1950s. The pace of this investment has increased in the past couple of decades. According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) to Africa grew at an average compound rate of 18% per year from 2004 to 2016. FDI refers to business investments made by entities from one country (China in this case) into another country. Lending activities by China in Africa dwarf their FDI investment. Financing of Chinese contracted projects in Africa has also been increasing and peaked in 2015 at USD$55 billion, almost twenty times the level of FDI. Similarly, by 2016, China was the largest exporter to Africa, accounting for 17.5% of African imports. By mid-2017, more than ten thousand Chinese-owned companies were operating in Africa. The largest companies by value are State-owned enterprises that dominate in energy, transportation, and resource sectors. Indeed, since 2010, a third of Africa’s power grid and infrastructure has been financed and constructed by Chinese state-owned companies.

Assertions regarding the motivations underlying China’s engagement in Africa have generated controversy with headlines such as “China in Africa: Investment or Exploitation?” or “Clinton warns against ‘new colonialism’ in Africa”. More recently, U.S. Secretary of State John Bolton characterized Chinese investment in Africa as predatory: “the strategic use of debt to hold states in Africa captive to Beijing’s wishes and demands.” These criticisms have only increased with China’s Belt and Road Initiative that encompasses several African countries. Proponents of Chinese investment in Africa have argued that these long-term investments foster greater independence of African countries because they do not have the paternalistic or imperialistic conditions often common with Western investments.

The implications for the Chinese investments and lending in Africa go beyond popular press headlines and political jabs to real and serious implications for development in Africa with concerns as to whether “China is making their [African countries] lunch or eating it”. More worrisome are fears that China may use its increasing economic power to extract concessions that may be economically and politically detrimental to the continent. As Steve Kull, director of the Program on International Policy Attitudes, noted, “China may feel that it is only natural it should seek advantages in its trading relations…”.

Chinese economic engagement in Africa has not gone unnoticed by U.S. policymakers. In 2018, The Trump administration’s “A New Africa Strategy: Expanding Economic and Security Ties on the Basis of Mutual Respect,” mentions China 25 times yet fails to mention Nigeria or South Africa—the largest economies in Sub-Saharan Africa. This strategy was more for countering China than engaging with Africa. Africa just happened to be the battlefield. This strategy has largely been maintained by the Biden administration. Tibor Nagy, former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, stated in the opening remarks of his testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee in November 2019 that U.S. strategy for Africa needed to “promote security and stability, expand trade and investment, harness the incredible potential of Africa’s dynamic people, and counter malign influence from China and Russia.” Whether or not Chinese economic engagement in Africa is a detriment to U.S. interests has not been systematically investigated. We focus specifically on the effect of Chinese economic engagement in Africa on diplomacy.

Our Study

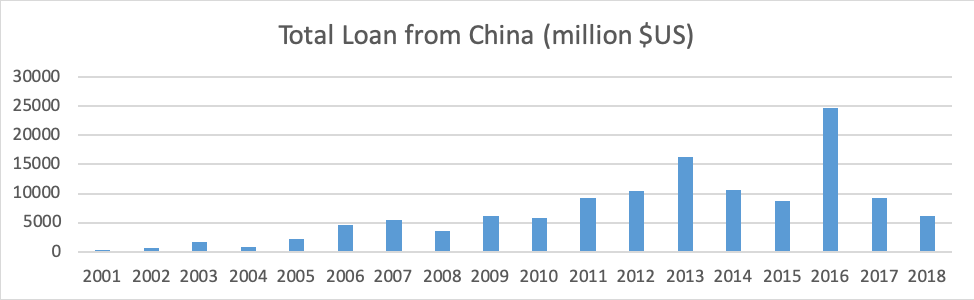

Our initial sample includes all 54 African countries from 2001 to 2018. We collect foreign direct investment (FDI) data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, which provides detailed bilateral FDI statistics from 2001 to 2012. We use the Chinese loan data provided by China Africa Research Initiative from School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, which covers all Chinese loans to African countries from 2000 to 2018.

International political alignment is indicated by ideal points. The ideal point is an indicator (constructed from the United Nations General Assembly voting data) of a nation’s foreign policy preferences. The ideal points have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 with lower values indicating deviance from the U.S.-led liberal order and higher values indicating conformity to the U.S.-led liberal order. Ideal points are a more consistent measure of two countries’ alignment on political preference than voting agreement percentage, which can move dramatically due to changes in agenda even when the underlying preferences do not change.

Our Findings

Our data reveals a continuous increase in economic investment from China. The magnitude of economic investment (both FDI and loans) significantly increases beginning in 2008. The magnitude of loans from China to African countries surpasses the amount of FDI investment by at least 3 to 4 times. As stated earlier, Chinese investment via loans allows for more nuanced arrangements, processes, and repayment arrangements.

Except for Angola (especially in 2016), Chinese loans to Africa have stagnated since 2014. Angola alone accounts for about a third of Chinese lending to Africa between 2000 and 2019; these loans are repaid with oil shipments. A little less than half ($19 billion) was in 2016 alone granted to Sonangol, the Angolan state-owned oil company. Outside of Angola, links between economic engagement and resource extraction are more nebulous. We rather turn our attention to international politics.

International Political Alignment that follows Economic Engagement

It is fair to state that the days are long gone when China was characterized as “bereft of friends,” “a beacon to no one—and, indeed, an ally to no one”. China’s rise as an economic power has been followed by its “emergence as an active player in the international arena”. China’s investments in alternative aid flows do not align with the idea of “aid” in the strictest meaning of the term. These projects often include a grant element of at least 25% (or higher) and typically come in the form of export credits, military assistance, or commodity-backed loans (with generous forgiveness terms). Further, China’s increased international activism has been reflected in many foreign policy arenas such as global climate talks, global economic and financial systems reform, and water diplomacy. Central to China’s foreign policy is the willingness to align and cooperate with other countries to build a multipolar international system that protects its interests in global politics. This is seen in coordinated policy positions and joint diplomacy in, for example, BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China), and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

Throughout the examination (2001–2018), our results suggest economic engagement with China yields greater political alignment between China and African countries. Over the 18-year examination period, political alignment between China and African countries increased by about 80%. In essence, China’s investment in Africa ensures that its investment results in greater global consensus around Chinese interests. Finally, since African countries are more dependent on economic engagement, their willingness to oblige by China’s wishes, especially regarding international issues, is strengthened due to their inability to exist without outside economic engagement.

But Less Alignment with the U.S.

Similarly, we investigate how political alignment with the U.S. changes over the observation period. At the beginning of the observation period, alignment with the African countries and the U.S. is low. This trend continues throughout the period and becomes increasingly negative. Over the 18-year observation period, misalignment between U.S. and African countries drops by about 8%. To the extent the African countries are decreasing alignment with the U.S., they are becoming increasingly aligned with China. Our results further suggest that greater alignment between China and African countries yields greater misalignment between African countries and the U.S.

Quantifying the Effects of Chinese Economic Engagement on African Countries Voting Alignment with China and U.S.

We analyze the effects of FDI investments and loans from China on the change in political alignment. We find that FDI investment from China is positively related to an African country’s change in political alignment with China. Specifically, between 2001 and 2012, every $1 billion investment resulted in approximately an 8% increase in the average political alignment with China. This effect, however, has not always been present. From 2001 to 2007, FDI investments and loans from China did not influence the political alignment of African countries. However, during the period between 2008 and 2012, every $1 billion investment resulted in approximately a 17% increase in average political alignment. Our data reveals that economic engagement achieves greater alignment post-2008.

The finding that FDI and loans from China to Sub-Saharan Africa increased their political alignment with China does not necessarily mean they are less aligned with the U.S. This finding could simply reflect greater global alignment on non-controversial issues. As such, we also examined how Chinese FDI investments impacted alignment between African countries and the U.S. We find that FDI investment from China reduces African countries’ political alignment with the U.S. Specifically, between 2008 and 2012, every $1 billion investment resulted in an approximate 1.3% decrease in average political alignment with the U.S.

Lastly, loans from China are also positively related to an African country’s change in political alignment with China. Specifically, between 2001 and 2017, every $1 billion investment resulted in approximately a 5% increase of average political alignment. However, between 2008 and 2017, every $1 billion investment resulted in approximately a 4% increase of average political alignment. Our data reveals that, post-2008, economic investment via loans achieved slightly less political alignment.

Loans from China do not predict the change in political alignment between African countries and the U.S. However, loans have a negative relationship with the average level of political alignment.

Conclusion: Implications for U.S. Policy

Our research reveals two primary implications. The first implication suggests that although, Chinese economic engagement in Africa is thought to be high, Chinese funding is still a very small percentage of African development or investment needs. There is room for more than one investor; therefore, Chinese involvement in Africa should not create an either-or proposition.

The second implication offers insight on the relationship between economic engagement and political alignment. Between 2001 and 2018, China loaned approximately $126 billion to African countries. Between 2001 and 2018, China invested $41 billion in FDI. The voting alignment index between African countries and China was -0.085 in 2001, and -0.019 in 2018. Thus, the investments from China resulted in 78% greater voting alignment. Between 2001 and 2012, the U.S. invested $56.3 billion FDI into Africa, but it also spent $9 trillion on the war on terror (portions of which are in the African Sahel region and the horn of Africa). During this time however, African countries’ voting alignment index with the U.S. dropped about 8% from -2.624 to -2.833. Clearly, economic engagement is more effective than military engagement for garnering friends.

Appendix

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News