When President Donald Trump lost the 2020 US presidential election to democratic candidate Joe Biden, many leaders in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) saw an ominous warning that democracy may again take center stage in US foreign policy, with autocrats trying to consolidate power in their hands.

However, China and Russia have added fuel to their authoritarian march by issuing a remarkable joint statement on February 4, aimed at redefining democracy as part of an effort to challenge the post-World War II order and make it more suitable for their interests.

And, as Russia wreaks havoc on the border and gears up for a military invasion of Ukraine and China’s military harassment of Taiwan intensifies, democratic expansion is coming up against aggressive—and sometimes bloody—resistance by Moscow and Beijing.

The declaration, issued during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Beijing for the inauguration of the 2022 Winter Olympic Games—which was hit with a diplomatic boycott by the United States and western allies over China’s human rights record—align with the rising trend in MENA of redefining human rights and what they really mean.

The statement denounces the US championing—under the Biden administration—a refocus on reviving democracy and supporting media independence and freedom of speech and assembly. It also puts forward an alternative political model tailored for the two countries’ political systems that fit all autocratic leaders’ agendas worldwide.

The statement condemns the US advancement of democratic values as a “one-size-fits-all template to guide countries in establishing democracy.” It also emphasizes that human rights should be “protected in accordance with the specific situation in each country and the needs of its population,” and that Beijing and Moscow “oppose the abuse of democratic values and interference in the internal affairs of sovereign states under the pretext of protecting democracy and human rights.”

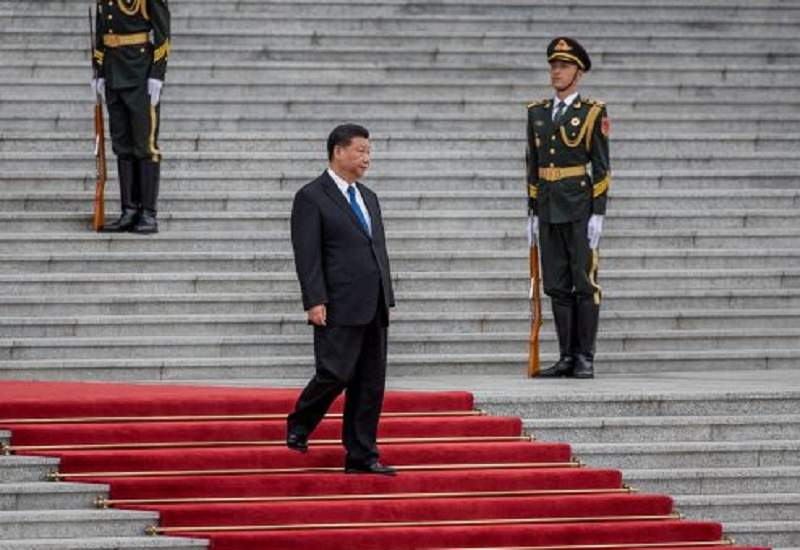

The “one-size-fits-all” critique of the liberal order was previously leveled at the US by President Xi Jinping in a political conference, following China’s Communist Party centenary on July 1, 2021.

In this ideology-heavy approach and the language used to promote it, China is increasingly taking the lead in the ideological confrontation with the US over democracy and human rights. And Russia is tacitly showing its conformity to China’s philosophy.

To be sure, China believes that regional stability in MENA requires economic and social development. It positions itself as a major power ready to facilitate this paradigm through strategic partnerships and Belt and Road Initiative investments. This partly stems from the Chinese formula of “peace through development” as opposed to the Western democratic peace doctrine.

In other words, China believes that the real priorities of countries in the region lie in economic prosperity and enhancing social cohesion and not through importing Western democratic values.

The Chinese leadership defends rethinking human rights. In this hypothesis, the citizens, first and foremost, have the right to a degree of social and economic welfare, where their freedoms, perceived interests, and views should toe the government’s line or be seen as a direct threat to national security and the nation’s development path.

While the Chinese Communist Party doesn’t aspire to promote Marxist-Leninist ideas to MENA or any other region, it seeks to legitimize its authoritarian model and popularize China’s success in economic development. Similarly, China uses its handling of the coronavirus pandemic as proof that its political system—which it calls “whole process democracy”—is more superior, effective, and capable of delivering than liberal democratic systems, especially that of the US.

During the same centenary conference last year, Xi was clear about what seems like China’s new clear-eyed goal. He stated: “China’s Communist Party is willing to exchange and share experience with political parties of all countries… so we can do more good for our people and people around the world.”

It’s safe to say that Chinese and Russian determination to challenge US leadership in advocating democratic values will be warmly welcomed by three different types of regimes in the MENA region: nationalist republicans, monarchies, and Islamists.

Despite their ideological differences and historical divergence in terms of state-building and other cultural aspects, they all see China’s and Russia’s debate around democracy, human rights, and the West’s longstanding tendency to deploy them to achieve political ends as an overdue process. Most of the US’s partners and rivals share the view that the US should understand “Middle Eastern exceptionalism.” In other words, the region’s exceptionalism lies in its inability to democratize, as some MENA leaders argue, as the state was historically built on religion’s enhanced role in building the nation’s identity, the nature of the state-society relationship, and the region’s civilizational and cultural uniqueness.

This view was widely shared among MENA governments after the 2011 Arab Spring. Since the uprisings, the last decade has witnessed the speedy rise of a “new authoritarianism,” which has occurred simultaneously with the rise of China’s aspirations to challenge US global leadership. Its champions, such as Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who toppled Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi and seized power in 2013 after mass protests, have been aggressively promoting a more centralized development model based on the enhanced role of the state. This includes an alternative economy-focused explanation of human rights and the justification of draconian measures against dissent as necessary national security policies aimed at preserving either the state’s very existence or its nation-building efforts, including its fight against “terrorism.”

China and Russia’s statement on democracy comes at a bad time for the Biden administration, as it coincides with an already vigorous push by some MENA leaders to nip any call for political pluralism in the bud and consolidate their power. Not surprisingly, as the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance notes in their report, The Global State of Democracy 2021, “The Middle East and North Africa remains the least democratic region in the world.”

In 2019, Sisi changed Egypt’s previously-liberal constitution so that he could stay in power until 2030 and enhance the already central role of the military in Egyptian politics, with the aim of further “preserv[ing]” the constitution and “maintain[ining] the basic pillars of the state and its civilian nature.”

Since July 2021, Tunisian President Kais Saied has broadened his authority by freezing the democratically-elected parliament and sacking the government. And, on February 6, Saied topped his authoritarian scramble by dissolving the Supreme Judicial Council; in effect, ending the separation of power and potentially blocking its path to democratic change.

In Sudan, the military generals sidelined their former civilian partners in a military coup in October 2021 and now enjoy running an almost military-colored government. Meanwhile, Jordan’s senate has passed new constitutional amendments in January to further reinforce King Abdullah II’s powers—just less than a year after the April 2021 alleged failed coup by his half-brother, Prince Hamzah.

The Gulf monarchies see China’s model with a similar eye. One of the main pillars of their cooperation with Beijing is non-interference in each other’s affairs—namely supporting each other’s internal measures—be they authoritarian or not—to safeguard stability. This approach saw Gulf and other MENA states endorsing China’s authoritarian policies against the Uyghurs as “anti-terrorism” measures.

Although Turkey is perhaps the only country in the region to express its opposition to China’s treatment of the Uyghurs minority, its Islamist-leaning President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has worked strenuously to reduce freedom of expression, censor the media, and prosecute dissidents. And, in Iran, another Islamist regime, the hardliners, who are currently running the country under President Ebrahim Raisi, aspire to China’s model and, like China’s leaders, are convinced that jobs, economic growth, and oil wealth can be used to entice citizens to ignore demands of political pluralism.

Russia and China’s message isn’t only attractive to leaders who prioritize economic development over political modernization. Autocrats from all ideological leanings could also consider it the new authoritarian playbook.

Democracy has never been a top priority for the MENA populace. Compared with China’s system, democracy now doesn’t even look like an appealing option for many in the region, as people increasingly buy Chinese leadership’s drive to “tell China’s story” abroad, with the pandemic-related success at the center of this endeavor.

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism. To show its willingness to cut with the Trump era, the Biden administration should first work on bolstering democracy defenses at home. It should then put up great resistance by shoring up its democratic alliances abroad, pushing back against the cyber authoritarianism that China has mastered, and commanding economic projects to help improve people’s lives and show that democracy can still deliver.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News