Airwars says it worked with the military to identify incidents, but newly classified docs show that in many cases, they were ignored.

For many years during the international air campaign against the Islamic State, Airwars participated in information sharing with the U.S.-led Coalition on civilian harm incidents. The results from that cooperation, as we’ve now found, have been underwhelming at best.

When local Syrian and Iraqi sources alleged civilians had been killed or injured, the Coalition would review the event and on multiple occasions ask Airwars for specific assistance. These official Requests for Information (RFIs) ranged from seeking the coordinates of a specific building, to requesting details about how many civilians died in particular strikes or neighborhoods.

Airwars’ team would then pore over our own archives and send back a detailed response. While there were periods when our relations with the Coalition were challenging, we continued to work privately with its civilian harm assessment team for several years in the hope that our assistance would lead to more recognition of civilian harm.

Yet a newly published trove of more than 1,300 previously classified military assessments, released by The New York Times after a lengthy lawsuit, has highlighted that the U.S.-led Coalition’s internal reporting processes for civilian harm were often defective and unreliable. This, The Times asserts, led the Coalition to radically underestimate the number of Syrian and Iraqi civilians it killed.

Those assessments of civilian harm also provide an opportunity to assess how the Coalition itself carried out the RFI process.

Airwars selected a sample of 91 incidents between December 2016 and October 2017. In each case, the U.S.-led Coalition had specifically reached out to Airwars requesting further details on alleged civilian harm. In 70 of these cases, we were able to match our response directly to declassified assessments in the Times database.

The results are concerning.

In total, in only three of the 70 cases where the Coalition asked Airwars for more information did it eventually go on to accept having caused civilian harm. The other 67 incidents were deemed “non-credible.”

“No specific information”

Airwars’ monitoring has found that at least 8,168 civilians have likely been killed by the U.S.-led Coalition during the campaign against ISIS. The Coalition, however, has accepted responsibility for 1,417 such deaths.

We identified three worrying trends in how our information was treated during the RFI process. The first was that the Coalition sometimes closed assessments before we had even provided our feedback, or did not reopen them when new information was provided.

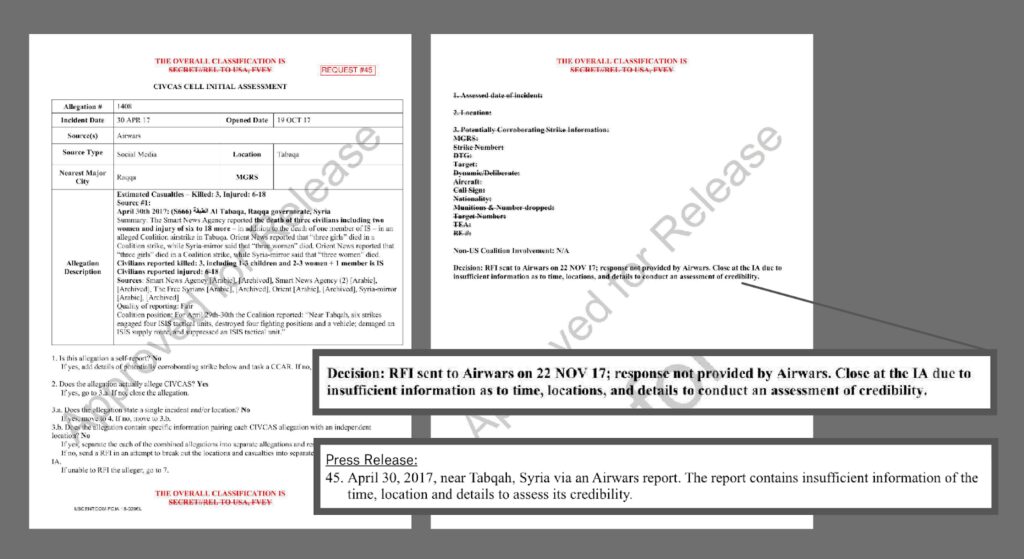

On April 30, 2017, for example, three civilians were reportedly killed in an apparent airstrike near a roundabout in Tabaqa in western Raqqa, Syria, with up to 18 more people wounded. All sources attributed the attack to the U.S.-led Coalition which was, at the time, involved in one of the most intense stretches of its grinding campaign against ISIS — striking dozens of targets a day.

In the middle of 2017, Airwars wrote to the U.S.-led Coalition raising concerns about this incident.

The Coalition opened up an initial assessment on the event, later that year — sending an RFI to Airwars on November 22nd with a simple question: “What are the coordinates for the alleged CIVCAS?”

Airwars provided close coordinates for the event to the Coalition following work by our own geolocations team. We also included a satellite image of the likely location — a 350 x 260-meter area northeast of the roundabout.

But the documents show that some time before our email was sent, the Coalition had privately deemed the event to be “non-credible.” It asserted that the claim needed to “be more specific to justify performing a search for strikes.”

Even after receiving Airwars’ response, there is no evidence the case was reopened. A year later, a press release declared that there was “insufficient information of the time, location and details to assess its credibility.”

In total we found at least 18 such cases where the Coalition had already reached non-credible determinations before we had responded. In none of these cases was there any evidence they reopened the file.

A second dispiriting trend was how rarely Airwars’ work prompted further review.

The vast majority of Coalition probes stopped at the initial assessment stage — a series of yes/no boxes where a single “no” leads to the allegation being deemed “non-credible.” In only seven of the 70 cases were any additional steps taken — in most cases turning an initial assessment into a Civilian Casualty Assessment Report (CCAR). These are longer assessments – but again, often end in non-credible determinations.

A third trend was that in cases where Airwars itself was not able, from local reporting, to specify exactly which civilians were killed in which particular locations, the Coalition almost always rejected such allegations. In 15 cases, the Coalition closed the assessment rather than search multiple areas.

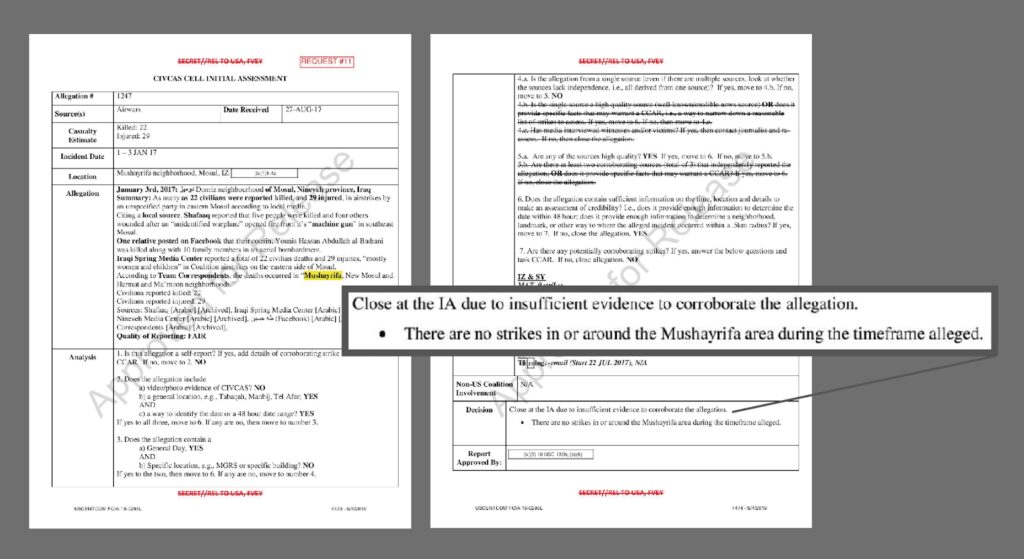

A typical case was the strikes on January 3, 2017 which killed up to 22 civilians and injured 29 more in eastern Mosul, in northern Iraq.

A Coalition RFI asked Airwars which civilian casualties were attributed to which of three named neighbourhoods in Mosul — Mushayrifa, Hermat, and Ma’moon. We replied with the exact time and coordinates of an airstrike in Ma’moon. The corresponding document shows the Coalition investigation was then closed and deemed “non-credible”on the grounds that there were no Coalition strikes in Mushayrifa, even though we had provided an exact location in Ma’moon. It’s unclear whether the Coalition assessors investigated all three neighbourhoods identified.

Other claimed civilian harm events were closed despite there being credible information provided not just by Airwars, but other major NGOs — such as an airstrike on April 28, 2017.

Fifteen members of the Dalo family, including five children under the age of 10, and three members of the al Miri’i family, were killed by a suspected Coalition airstrike on a residential home. A Human Rights Watch investigation released months later found the remnants of a Hellfire missile linked back to Lockheed Martin, one of the U.S. military’s largest contractors.

Despite this wealth of evidence, and Airwars providing coordinates for the district the street was in, the U.S.-led Coalition deemed the event “non credible.”

How it should work

Our research did uncover at least one case where Airwars provided information which then helped change the internal designation of an incident from non-credible to credible. This, in theory, was how the system was meant to operate.

On March 21, 2017, civilians were reportedly killed and dozens more injured when Coalition airstrikes targeted multiple locations in Tabaqa, Syria.

In October, the Coalition asked Airwars for the locations of each of these sites. We provided exact coordinates for the majority, and neighborhood-level coordinates for the rest, alongside annotated satellite imagery.

The Coalition then used this information to review its own strike database. Three corroborating strikes were identified, of which two were assessed to have led to civilian harm —one death and one injury. However, the Coalition’s admission still contrasts drastically with the numbers reported by local communities, which alleged 10 to 20 civilians were in fact killed.

Were the Coalition to have treated other cases in the same manner, it might have accepted responsibility for many dozens more fatalities. Instead these civilians remain uncounted, and their families’ questions unanswered.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News