Aleppo was devastated by bombing and shelling during the Syrian war. It remains unsafe, with residents subject to shakedowns by the regime’s security forces and various militias. Damascus and its outside backers should curb this predation as a crucial first step toward the city’s recovery.

What’s new? Almost six years after retaking Aleppo, the Assad regime is again largely in control, but the city is a shadow of its former self. Many neighbourhoods remain in ruins from Syrian army shelling and Russian bombing. Militias roam the streets and an informal economy thrives, but there is little else.

Why does it matter? Aleppo was Syria’s largest city before 2011 and the hub of production, trade and services in the north. Its revival is key to the area’s long-term prosperity and stability. If a city of this importance cannot be rehabilitated, the future of other war-ravaged towns is bleaker yet.

What should be done? Damascus, plus Russia and Iran, could aid Aleppo residents and its formerly vibrant entrepreneurial class by reining in militias, restraining security agencies and regime cronies, and ending the persecution of people accused of opposition links. Large-scale reconstruction is off the table, but small internationally funded “recovery” projects can ease hardship.

Executive Summary

Aleppo offers a glimpse of the grim realities of post-war Syria. It was the country’s largest city and its economic engine before the Syrian army and Russian air force bombed entire neighbourhoods into rubble, displacing most of the residents. Many people have yet to return and businesses to recover, as government-linked militias stake out turf, looting homes, demanding bribes and engaging in other forms of predation on those who have remained. The regime of President Bashar al-Assad and its allies are doing little to get the city back on its feet. Business leaders resent the arbitrary rule of state security agencies and the regime cronies in their shadow; many are leaving as an unhealthy economic climate perdures. Although they have shown little appetite for doing so thus far, Russia and Iran have an interest in using their influence to stop unruly militias from extorting residents and stealing property. Those steps would help revive the city.

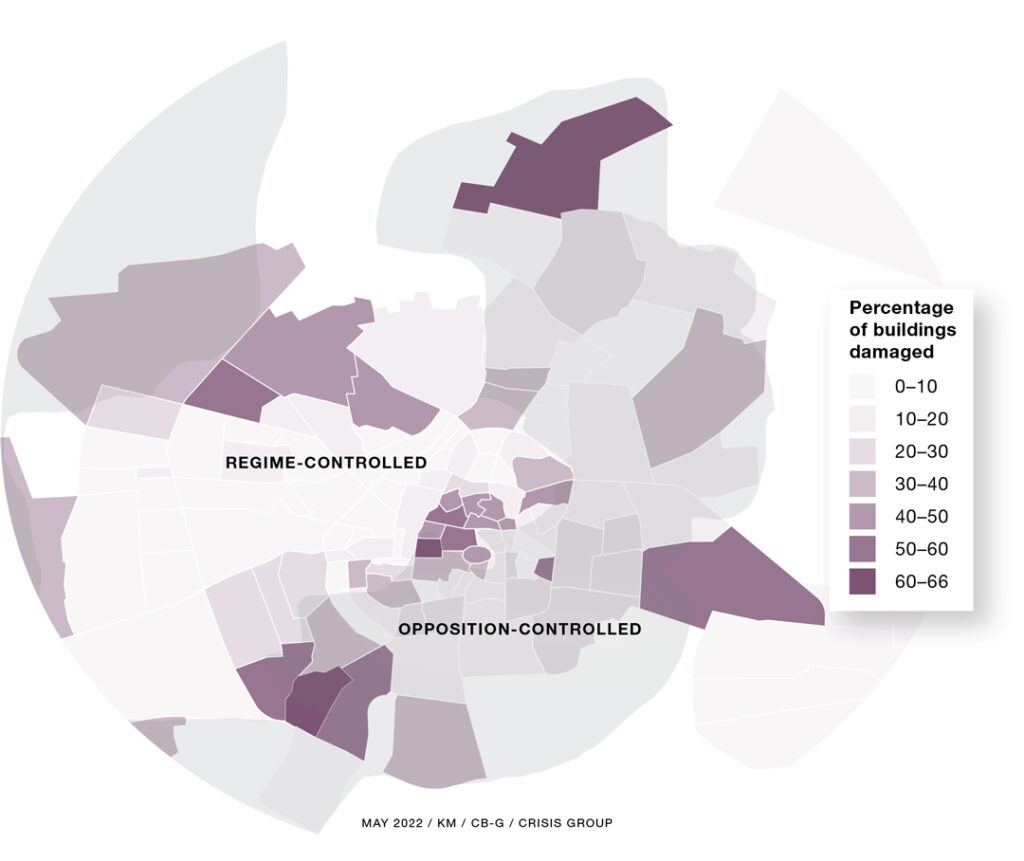

Fighting came to Aleppo in mid-2012, spreading from the surrounding countryside and splitting the city into zones of regime and rebel control. Rebel-held areas were primarily informal settlements populated by labourers hailing from the hinterlands, while regime-held Aleppo, including primarily the city centre and its western flank, consisted of more affluent neighbourhoods. While the latter part of the city suffered damage, and the quality of public services and access to basic goods declined, an indiscriminate bombing campaign by the regime and its Russian ally destroyed and depopulated entire swathes of the former.

With Russian airpower and Iranian technical advice and ground support, the regime drove rebels out of Aleppo in late 2016 and fully retook the city. Yet the rebels’ defeat has not meant a return to stability, let alone prosperity, for Aleppo’s inhabitants. Large areas of the city remain in ruins and there is no evidence of a coordinated state vision or effort to rebuild them beyond estimating the number of destroyed buildings.

The security situation remains shaky. Regime forces have primary but not exclusive control of the city, as militias, though nominally aligned with the regime, engage in sporadic clashes with soldiers and one another and harass residents. Rebels are ousted, no foreign player has an interest in renewed intervention to challenge the regime and the population is too exhausted and impoverished by years of war, and too preoccupied with meeting basic needs, to stage another uprising. Moreover, most of the city’s inhabitants who were displaced to opposition-held areas or abroad have been unable to return, mainly because they fear either conscription or reprisal for their suspected involvement in the revolt.

Economically and socially, Aleppo is nothing like it was before the war. Regime-allied militias backed by Iran and Russia operate openly in neighbourhoods throughout the city, looting properties and shaking down residents at will. They and the security forces also levy heavy taxes on the city’s major economic activities: trade in products flowing in from the outside and lucrative generator monopolies to supplement meagre state electricity provision. These conditions make Aleppo’s industrialists, many of whom moved their operations to neighbouring countries in the war’s early years, loath to risk reinvesting in their native city. Many of the skilled workers they formerly employed have also left and the constant threat of conscription facing all young males makes the supply of labour insecure. This situation renders the chances of even a partial return to the city’s pre-war economic vibrancy slim.

The Syrian regime lacks a comprehensive plan, much less the capacity, for rebuilding the city, and nothing suggests that international assistance is forthcoming. Neither of the regime’s backers, Russia and Iran, has expressed an intent to spend large sums on reconstruction. Western actors remain committed to a national political transition, believing that without it major investment will only reinforce the regime’s repressive rule and thereby aggravate the conflict. Some Gulf Arab states, notably the United Arab Emirates, have signalled that they may be prepared to support reconstruction, perhaps hoping to pull Syria out of Iran’s orbit and roll back the Turkish encroachment in the north, but they worry about running afoul of U.S. secondary sanctions on dealings with the regime. International organisations have expanded their humanitarian work but struggle to navigate a maze of often incoherent donor limitations on their mandate. They also face scepticism among beneficiaries who often doubt their bona fides, precisely because the regime has assented to their presence.

” The regime has moved to strengthen [militias and security services] … in order to control society through a mosaic of fiefdoms. “

There is no early prospect of Aleppo – or any other Syrian city heavily damaged in the war – returning to its pre-2011 levels of prosperity or human well-being. Indeed, the experience of this city and other parts of Syria suggest that, rather than restrain militias and security services that exploit average citizens and businesses, the regime has moved to strengthen these elements in order to control society through a mosaic of fiefdoms. At the core of this form of rule is a shift from purely arbitrary predation on local populations during wartime to post-war plunder that sometimes comes with the trappings of legal procedure but is still unaccountable and stands in the way of even a modest recovery.

The city could nonetheless be made more hospitable for its entrepreneurial classes and more liveable for its residents. While large-scale reconstruction aid is out of the question, small internationally funded projects – reviving bakeries, for example, or restoring health facilities and sanitation systems – could help ease suffering, though offering no hope in themselves of bringing about structural change.

A far more consequential step would be for the Syrian regime, Russia and Iran to curb the predation of militias and security agencies, as well as regime cronies acting in the slipstream of, or in collusion with, the men with guns. Damascus has previously taken such action with smugglers and its own security agencies when they overstepped their bounds, while Russia and Iran could rein in militias and security agencies under their sway. At present, without complete control of Syria’s borders or territory, the regime lacks key aspects of statehood, meaning that Russia and Iran must periodically prop it up. Helping curb the chaos in Aleppo could relieve this headache for Moscow and Tehran in at least one important locale. Damascus and its foreign allies may be unable to stop the predation entirely, but if they can reduce its severity, they would help the city take a crucial first step toward recovery.

Aleppo/Beirut/Brussels, 9 May 2022

I. Introduction

The people of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, largely stayed on the sidelines, when the March 2011 uprising erupted and rapidly spread throughout the country.

The city’s prosperity under President Bashar al-Assad was built upon links to the regime that many Aleppans, regardless of their politics or personal feelings, were reluctant to break. But in late 2011, regime attacks on rebels around Aleppo spurred demonstrations and clashes with state agents in the city’s eastern neighbourhoods, where rural migrants had settled in the preceding decades. In March 2012, the previous year’s small, sporadic demonstrations rapidly grew into violent confrontations with regime forces.

By mid-2012, many neighbourhoods in eastern Aleppo had fallen out of regime control. Damascus retained its grip on the city centre and affluent areas in the west, while rebels associated with the Free Syrian Army, the umbrella organisation of armed groups opposed to Assad, defended neighbourhoods they had seized in the east. Local residents in these rebel-held areas established committees to administer services formerly provided by the state. Rebel successes in this part of the city became a model of how to drive out regime elements and hold territory. Because of these accomplishments and Aleppo’s economic and strategic significance, the city became a bellwether for the entire rebel effort.

The regime’s response underscored the importance it attached to the city and its immediate environs. As rebels took more of the surrounding countryside, the regime fought fiercely to keep its hold on western Aleppo.

In late 2013, it began rolling barrels and dumpsters packed with explosives out of helicopters, indiscriminately striking civilian homes, hospitals and schools, as well as rebel units. Russian airpower helped prepare the ground for an eventual regime offensive. That came in December 2016. It rapidly overwhelmed rebel defences, paving the way for a Russian-mediated deal between the regime and the rebels to evacuate the latter and their families to rebel-controlled areas in the Idlib and western Aleppo governorates.

After the evacuation, regime forces and allied militias became the dominant military powers in much of Aleppo, but their rule could hardly be described as creating a stable political or social order. Skirmishes with small rebel groups continued in subsequent years.

These included the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which retained control of most of the city’s Kurdish-majority neighbourhoods of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiya. Other areas that the regime had lost during the war remained largely destroyed and depopulated for several years afterward.

There are no systematic plans to rebuild any of them.

” Eastern Aleppo provides an example of the new realities in post-war Syria, shedding light on the emerging order in cities recaptured by the regime. “

Eastern Aleppo provides an example of the new realities in post-war Syria, shedding light on the emerging order in cities recaptured by the regime. It has the greatest number of damaged buildings of any Syrian city.

Many other cities have suffered devastation, such as Deir al-Zor and eastern Ghouta, a vast suburban area of Damascus, which saw even higher rates of destruction per hectare than eastern Aleppo, while entire districts of Homs and Hama have likewise been left in ruins.

The predatory relationships that exist in many of these places today – between the regime and allied militias, on one hand, and the population, on the other – emerged in the aftermath of this destruction.

Aleppo’s fate also bears on the socio-economic well-being of Syria’s entire north. The city was an important economic and administrative centre before 2011. Raw materials and bulk goods flowed through it. The region’s residents came to town for administrative services and advanced medical treatment. Local industrial production generated much of the area’s economic growth.

This report analyses how regime and militia rule over what remains of eastern Aleppo prevents a return to stability and a revival of the local economy. It examines the limits of what Western donors can hope to achieve. It also proposes steps the regime and its external sponsors could take to improve conditions. It is based on some 45 interviews conducted in Syria, Lebanon and remotely in November 2020-February 2022, as well as analysis of satellite imagery. It builds on Crisis Group’s four previous reports on Aleppo and the north of Syria since the uprising turned into civil war.

II. Unruly Militias and Other Armed Actors

The risk of renewed armed conflict in Aleppo city is remote, as the regime and allied militias are dominant enough to stamp out any coordinated challenge to their authority. Yet the security situation is hardly stable for average citizens. Periodic clashes between militias and predation upon residents remain constant threats.

Pro-regime militias arose during the fight for Aleppo between 2012 and 2017, through both residents’ initiatives and security agencies’ encouragement. Residents with strong ties to the regime created “popular committees” (lijan shaabiya), funded by pro-regime businessmen, many of which later joined the National Defence Forces (NDF), the umbrella group of paramilitaries directed by regime security figures.

These militias took on a number of tasks – defending their neighbours, fighting rebels on front lines, smuggling goods into the city for supporters and looting property of regime opponents – often with the support of the regime and its foreign backers, Iran and Russia. As the conflict over Aleppo tapered off, these militias refocused on enriching themselves while retaining ties to their patrons. Militia activity inside Aleppo receded somewhat in 2021, largely because the regime sent many fighters to fronts to the city’s north and east. The militias remain a major presence, however, and state security forces, to the extent that they have taken the militias’ place, behave in much the same ways.

A. From Cooperation to Destruction

Before 2011, Aleppo was a vibrant economic centre and a primary engine of Syria’s economic growth. The city had historically been a hub of commercial activity for the entire region, with business relationships underwritten by trust built between trading and business-owning families over several generations.

Trade and, especially, manufacturing grew substantially in the decade preceding the 2011 uprising.

This prosperity was a function of collaboration between the city’s business elites and economic migrants from Syria’s hinterlands, with the latter working in the former’s factories and workshops. Although these two groups cooperated and depended on each other, they lived largely apart. The more affluent business families resided primarily in the old city centre and the villas and tower blocks on its western flank, while the migrants built spontaneous, informal settlements, mainly to the city’s east, but also extending to the south and south west, in a conurbation colloquially referred to as “eastern Aleppo” (see Figure 1). Marriages across the residential barrier were exceedingly rare and the migrants, who were largely of tribal background, brought with them rural patterns of fertility and extended family solidarity.

The fighting that took place between 2012 and 2017 tore the city’s social and physical fabric. Battle lines between rebels and the regime largely followed the divide between the city’s affluent western parts and its informally built eastern periphery. The regime and its Russian allies resorted to indiscriminate bombing in areas where the rebels asserted control, but rebels lacked the heavy weaponry and air support to inflict anywhere near the same amount of damage on regime-held areas. As a consequence, eastern neighbourhoods suffered the greatest damage during the war (see Figure 2).

The fighting also destroyed businesses’ inventory and other physical assets. Industrial areas, though located primarily in the rebel-controlled east, were spared bombing. The regime’s primary targets were residential and commercial areas housing rebels and people loyal to them. Nonetheless, wartime circumstances allowed militias to loot industrialists’ storehouses.

Years of violent conflict also destroyed the trust vital to the functioning of the local economy. Not only did trading families take opposite sides during the war, but the looting and exploitation that were enabled by prolonged periods of fighting, and the formation of militias, upended pre-war relations, both within the city’s business class and between owners and their employees.

B. Enduring Insecurity and Predation

Since retaking eastern Aleppo in late 2016, regime forces and militias have met only limited, sporadic resistance from the population. Rebels in Idlib and the western Aleppo countryside are significantly weakened and have not attempted a major advance on the city since 2016.

The population chafes at the predation and arbitrary violence of regime forces and militias, yet Aleppo residents lack the capacity to mount a sustained protest campaign, being focused on subsistence and survival.

Following the rebels’ defeat, a patchwork of overlapping state security forces has returned to the city. Preeminent among them is the elite 4th Division of the Syrian Army, whose soldiers man the checkpoints on roads leading from the city to other provinces and to opposition areas.

Air Force Intelligence has the second most powerful military presence, with heavy involvement in coordinating militia activity and suppressing dissent. Several other official security agencies, including Military Intelligence, State Security and Political Security, focus on administrative tasks – executing the governor’s decisions, issuing identity documents and handing out business licences.

While this patchwork of security actors is effective in preventing coordinated challenges to the regime’s authority, the state hardly has a monopoly on the use of force in Aleppo. A range of militias linked to the regime and its allies are present throughout the city. In the eastern al-Sukkari neighbourhood, for example, both the Iran-aligned Liwa al-Baqir and Russia-aligned Liwa al-Quds are everywhere in evidence.

As a practical matter, anyone with a gun and wearing fatigues can exercise authority over average residents; a phrase many residents attribute to militiamen sums it up: “Hey, we are the state!” Militia members greatly outnumber police in many of Aleppo’s eastern neighbourhoods. Local notables, mukhtars (mayor-like administrators), Baath Party members and government employees sometimes act as intermediaries between armed men and residents to resolve disputes over issues like property rights and the size of bribes given to authority figures.

” The presence of so many militias makes the city vulnerable to unpredictable bursts of violence. “

The presence of so many militias makes the city vulnerable to unpredictable bursts of violence. The groups tend to be aligned with either Iran or Russia and frequently clash with one another – over turf and spoils, at times, and over personal matters, at others.

They even skirmish sporadically with regime agents.

All these actors, militia members and regime agents alike, prey on the population in various ways. Control over all checkpoints into and out of the city allows members of the 4th Division to levy hefty duties on people and goods passing through. The soldiers often tax the same goods multiple times, even when the owner can produce evidence of prior payment.

The tariffs extracted by state agents keep building materials prices in Aleppo, at least one third higher than in neighbouring Turkey, from which they are imported. Currency exchangers are regularly arrested and fined for small technical infractions – or reportedly kidnapped for ransom – by security forces. Additionally, residents allege that municipal officials and security officers take bribes to allow illegal rebuilding, and municipal workers clear rubble from streets of destroyed buildings to enable security agencies and militias to loot houses for valuables.

Non-state militias engage in similar forms of predation, notably the looting (taafish) of private homes.

Many rank-and-file militiamen hailing from outside the city live for free in seized flats in eastern neighbourhoods, while militia leaders are known to expropriate houses in wealthier western Aleppo. Residents are forced to call upon connections to high-ranking state and security officials (wasta) or pay rival militias large sums of money to push these leaders out of their homes. Militias also sell oil products smuggled from Syrian Democratic Forces-controlled areas and bread they have obtained from government bakeries (through their ability to skip bread queues, discussed below), all at a significantly higher price than the actual cost. Citizens are generally powerless to challenge the terms set by militia members for fear of retribution.

Regime security forces have gradually been pushing some militias out of the city since late 2020, dismantling their checkpoints and sending them, in the words of a police colonel, “to confront ISIS groups in the Syrian desert and on hot fronts in Idlib”.

This move may be aimed at restoring the authority of – and traditional competition between – the aforementioned four regime security branches. While some residents associate the growth of the security forces’ authority at the militias’ expense with a reduction in predation, for the most part, the city’s inhabitants see little in the way of positive change. Many militias still have a major presence in Aleppo, and to the extent they are gone, security forces have in many cases stepped into their shoes. The militias, meanwhile, are able to protect their members when the regime seeks to arrest one or more of them for criminal activity. State security forces also harass, detain and extort people simply for having relatives who live in opposition-controlled areas – even those who have completed formal “reconciliation” processes (see below).

The gradual strengthening of security forces provides a glimpse of the post-conflict order that is likely to crystallise in both Aleppo and Syria more generally. At its core is a shift among armed actors. In the place of armed groups’ arbitrary predation is more organised coercion that, because it is carried out by regime security forces, has the trappings of formal legal procedure. With little pressure on the regime to restrain security services, whether from international actors or organised residents, this sort of formalised predatory rule is unlikely to be disturbed in the short term.

C. Militias’ Social Roots

The most powerful militias in Aleppo have a range of social bases, but most have grown out of residents’ pre-existing family networks. Some, such as the Al Birri clan, were involved in crime, with security service complicity prior to the war, and expanded these activities after its onset. Long active in smuggling, Al Birri members aided the regime in repressing demonstrations during the 2011 uprising.

The largest militia, Liwa al-Quds, formed around Muhammad Said, a Palestinian nationalist militant, who served before the war as an intermediary between the Palestinians in Aleppo’s Nayrab refugee camp and the regime. Similarly, Kurdish extended families in the Ashrafiya and Sheikh Maqsoud neighbourhoods have their own militias. Several small NDF units are also composed mostly of members from the same extended family or neighbourhood.

Some regime-aligned militias also have ties to outside powers, notably Iran and Russia. Prominent among those linked to Iran is Liwa al-Baqir, a militia composed primarily of al-Baggara tribe members, who received patronage in return for loyalty to the regime before 2011. Many Liwa al-Baqir members were involved in repressing early protests and more recently converted to Shiism. The militia’s leader, Khalid al-Hassan, adopted the moniker Haj Baqir, using the honorific “Haj” and a single name, on the model of Hizbollah commanders, rather than a military title.

A second important Iran-linked militia is Faylaq al-Mudafaeen an Halab. The group started out as a Shiite-majority militia in the Aleppo and Idlib countryside – although with a significant portion of its membership drawn from regime-affiliated Sunnis of tribal background. It later gained a reputation for looting and for clashing with other militias and tribal communities, while fighting alongside the regime to expel rebels from Aleppo.

It acquired its current name in 2017. Its leader, who is known as Haj Muhsin and rumoured to be Iranian, took the helm after the militia’s original leader was killed in a suspicious traffic accident in 2018.

” Joining a militia is both a way of avoiding conscription and, for many, the only way to make money. “

While a few militias do have a stated ideology – for example the Democratic Union Party (PYD), which is present in the Kurdish neighbourhoods of Aleppo, dominates the Autonomous Administration in Syria’s north east and is associated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – it tends to be less important in keeping them together than family ties or issues related to personal security and subsistence.

Sometimes, these considerations overlap. For example, joining a militia is both a way of avoiding conscription and, for many, the only way to make money. A man from al-Shaar neighbourhood, from a rural tribal background, explained that because he could not feed his family of eight on his taxi driver’s salary, he allowed three of his sons to join a militia to which other relatives belonged. He said his sons later provided his family part of their salaries and an apartment free of charge. But generational Aleppans – ie, those who belong to families that achieved status through decades of economic and civic engagement – refused to deal with him and accused his family of looting and thuggery.

Tribal identity can play a role in the formation of, and recruitment into, militias, but it is a secondary factor. As the al-Shaar resident’s story suggests, family connections within tribes help pull members into a given militia, but entire tribes rarely align with a certain militia or foreign backer. Liwa al-Baqir, for example, is led by a member of the al-Baggara tribe and heavily associated with it, yet many tribesmen have joined opposition militias.

Other Aleppo tribes are partly associated with opposition factions, but no tribe entirely went with the rebels or stayed with the regime. In general, the regime attempted to retain clientelist links to tribal elders (wujaha) to create small pro-regime militias to shield itself from attack by rebels from the same tribe.

The general result of these dynamics on the ground is a reversal of the pre-war social order. Families that held most local economic power for generations have been shunted aside, while a new elite of warlords and militia leaders, primarily from the city’s periphery and surrounding countryside, has emerged.

The resentment directed at residents, such as the former taxi driver whose sons fight in militias, reflects the way that war has inverted hierarchies in the city and deepened the divide between generational Aleppans and those of rural background. The former view the economic (and military) power that pro-regime militias now hold as their own birth right. Few generational Aleppans belong to these militias.

” While elections in Syria have a veneer of popular choice, they are in practice controlled by the regime. “

A clear indication of this reversal of roles came with the 2020 parliamentary elections, when warlords gained seats at the expense of traditional business figures and regime clients. For instance, Fares Shehabi, an established Aleppo businessman with close ties to the regime, lost his seat. In contrast, Hussam Qatirji, a warlord from the Aleppo countryside, who became central to the oil and wheat trade between regime- and ISIS-controlled areas during the war, won a seat.

Conventional wisdom in the city was that Shehabi lost despite his longstanding ties to Damascus, because he was insufficiently pliable and deferential, while Qatirji won because his economic and military interests are directly aligned with, and subordinated to, those of the regime. While elections in Syria have a veneer of popular choice, they are in practice controlled by the regime.

D. International Approaches

The picture for international reconstruction aid is bleak. The U.S. and European countries have conditioned such assistance on a comprehensive political transition.

Their approach is based on UN Security Council Resolution 2254, passed in 2015, which stipulates a roadmap for such a transition. Given the Syrian regime’s unwillingness or inability to take even small steps in this direction, such a transition is unlikely short of regime collapse or removal by external military intervention. The support for Damascus from Moscow and Tehran makes these already highly unlikely prospects even more remote.

Moscow and Tehran have themselves put little effort into reconstruction to date, focusing instead on shoring up their strategic positions in the country. Russian investment consists primarily of contracts for natural resource extraction. Russian private companies have shown little interest in broader investment given the dim prospects of profit in wartime conditions.

Iran, facing its own fiscal challenges, has mostly limited itself to undertaking small reconstruction projects that support allied militias.

” Some Gulf Arab states have signalled that they might be prepared to support reconstruction … but, for now, they are hesitant to take the risk. “

U.S. secondary sanctions on Syria, imposed in June 2020, make other states, companies and non-governmental organisations even more reticent to invest in Syria. The 2019 Caesar Civilian Protection Act newly focused prohibitions of material support to, or business transactions with, the Syrian regime on non-U.S. entities. These sanctions’ vagueness and breadth have created a climate of over-compliance that has also affected donor governments, commercial entities and NGOs, causing some to avoid even small-scale projects.

Some Gulf Arab states have signalled that they might be prepared to support reconstruction, perhaps hoping to pull Syria out of the Iranian orbit and roll back Turkish encroachment in the north. But, for now, they are hesitant to take the risk.

The EU’s main activity on the ground in Syria has been providing humanitarian assistance, distributed mostly by the UN and international NGOs. Its member states have, so far, stuck to the line of Resolution 2254, requiring substantive political change before they will provide support for reconstruction.

There has, however, been a move by EU members to expand aid beyond basic humanitarian needs. Termed “humanitarian plus” or “early recovery”, this aid goes toward basic rebuilding projects, like rehabilitating schools, bakeries and sanitation systems, but stops short of full-scale reconstruction and the international loans and aid for infrastructure redevelopment it entails. In 2017, the EU high representative for foreign affairs, Federica Mogherini, proposed a “more for more” approach, under which early-recovery programs would be greatly expanded following concrete steps by Damascus toward political inclusion. This approach has not been fleshed out in detail, much less attempted, in large part because the regime has shown little willingness to reciprocate on even minor issues.

Some international humanitarian organisations have opened field offices in Aleppo. An Aleppo-based representative of one such organisation reported a corresponding palpable improvement of field access, in particular the ability to conduct need assessments and a generally cooperative attitude from local authorities.

Still, eastern Aleppo residents from a range of occupational and social backgrounds expressed to Crisis Group their scepticism that they would benefit from international aid, apparently convinced that the regime captures most of this assistance and directs international organisations’ local staff to distribute benefits only to people in regime-aligned areas.

III. Navigating Predatory Rule

New forms of governance emerging in post-war Aleppo have reshaped life on the ground. The militias’ arbitrary rule, violence and predation create often unpredictable risks and make the environment for inhabitants difficult to navigate. Economic conditions are harsh, with inflation eating away at the value of what meagre incomes residents can earn. Basic services formerly provided by the state, such as electricity, water and sewage disposal, are either absent or of very poor quality. Residents are thus compelled to pay a large portion of their income to private service providers (especially for electricity). All too frequently, they must do without basic services.

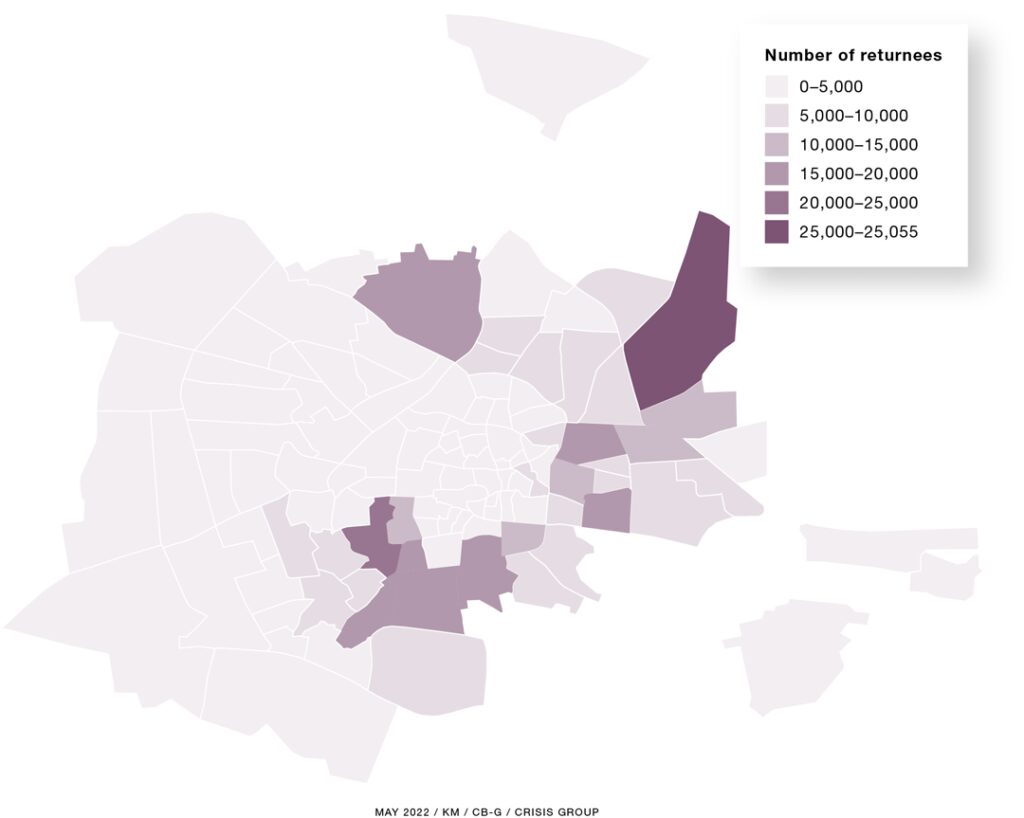

Some former residents of Aleppo are returning, but the population remains far smaller than before the war.

Returnees come primarily from regime-controlled areas. Aleppans in opposition-controlled Idlib or abroad fear arbitrary detention and abuse due to suspicion that they participated in, or supported, the opposition.

This environment similarly affects the economy and housing markets. The entrepreneurs who made Aleppo an engine of Syria’s economic growth in the decade before 2011 are among those most reluctant to return. Those who supported the opposition cannot return, while those who remained neutral or sided with the regime cannot see a way to turn a profit in a city deprived of its labour force and run by militias and security services. When former residents of the city’s heavily damaged eastern part do attempt to return, they encounter administrative barriers to rebuilding their homes, and militias pressing them to sell their houses for prices highly unfavourable to the owners or outright confiscating their properties.

A. Living Conditions

Signs of poverty are more evident today among Aleppo residents than in the immediate aftermath of the regime’s reconquest. Perhaps the most important factor in the deterioration of living conditions – both in Aleppo and throughout the country – is the lira’s collapse. The Syrian currency has lost 85 per cent of its value since Aleppo was retaken in 2016 and nearly 99 per cent since early 2011.

War has made Syrians rely on imported goods even more than before 2011, so the lira’s devaluation has made meeting basic needs a struggle for much of the population. To make matters worse, pressures on state finances have led to cutbacks in state subsidies for goods, on which most of the population depends; a January 2022 government directive trimmed by 15 per cent the roll of citizens eligible for subsidised goods, including food and fuel, with further cuts planned. Even Syrians receiving money from relatives abroad find that many products are unavailable in markets.

One such product is government-subsidised bread. People throughout Syria wait in lines for several hours to buy the loaves, whose quality has deteriorated following a national wheat shortage.

Subsidised bread is sold for 250 lira ($0.07) per 1.1kg bag, while unsubsidised bread costs 1,350 lira ($0.38) for the same quantity. One reason for the shortages at government bakeries is that much of the bread produced there is diverted. Among the culprits are police, security officials and militia members, who skip queues via “express” lines, and private vendors who sell the bakeries’ bread outside the premises for multiples of the subsidised price, often in plain sight of security officials and police. (Hours-long queues alongside “express” lines are also visible at petrol stations.

)

” Buildings damaged in fighting, primarily by regime and Russian air bombardment, routinely tumble down and kill people still living in them. “

Much of the city’s physical infrastructure remains in ruins. Al-Kindi University Hospital, Syria’s largest pre-war medical facility, exemplifies this problem. Taken over by rebels in 2013 and destroyed by regime bombing, the hospital has since been looted for metal and supplies and sits idle; most qualified doctors have left and those remaining lack medical supplies.

In addition, buildings damaged in fighting, primarily by regime and Russian air bombardment, routinely tumble down and kill people still living in them. A 2019 government study found that thousands of residential buildings are in danger of imminent collapse. In December 2021, state authorities staged emergency evacuations of three buildings that had sustained major damage during the war; two of them crumbled on their own before workers could knock them down.

The electricity grid and generation capacity were also badly damaged in the war and have yet to be repaired. In western Aleppo, residents are entitled to state-provided electricity for half the day, on a three-hours-on, three-hours-off schedule. This schedule is frequently interrupted in winter peak demand months, when oil supplies run out and the poorly rebuilt power grid breaks down. Much of the city’s eastern part receives only a few hours of state-provided electricity a day under ideal conditions.

Residents thus turn to private generator operators to secure electrical power. The first generators were set up in 2013 by NDF members, but today many are run by whichever armed group is dominant in the neighbourhood. Russia- and Iran-backed militias control the electricity market in eastern and central Aleppo; Kurdish family militias do the same in Sheikh Maqsoud; and Military Intelligence provides power to the Halab Jadida neighbourhood, where its headquarters are located.

Many labourers and state employees spend a significant fraction of their salaries on electricity. Mid-level government employees are paid salaries of between 60,000 and 70,000 lira ($17 to $19) per month and manual labourers earn between 3,000 and 10,000 lira ($1 to $3) per day. The amount of generator power needed to run basic electric appliances typically costs about 240,000 lira ($70) per month.

Of course, residents have other expenses than just the power supply.

Average residents of Aleppo and business owners alike complain about the pricing by generator operators, who charge consumers multiples of the state-set tariffs for supplemental electricity and frequently provide far fewer hours of coverage than agreed, while demanding additional payment to repair broken equipment.

Fares Shehabi, a prominent Aleppo businessman, who is not involved in the generator economy, expressed this frustration publicly in January 2021, claiming that the real goal of state rationing policies is to promote the business of generator operators. He went so far as to compare the state-run electricity company to ISIS, citing the generator economy’s negative impact on the city’s business climate and people’s livelihoods.

Yet the strain that electricity prices place on Aleppans’ budgets is also a function of the lira’s collapse. The market rate is around 10,000 lira ($2.78) per ampere per week for eight hours of electricity daily.

Based on a World Bank study of the generator economy in Lebanon and market diesel prices in Aleppo, a generator operator would have to charge 6,100 lira ($1.69) to break even.

Generator operators are thus enjoying margins of 39 per cent, a tidy profit, but not the many multiples of their costs that residents allege.

In other words, while citizens are at least partly mistaken to blame generator operators for high prices, they certainly face hardship in paying. Moreover, this analysis suggests that even generator operators face extremely high costs as a result of the lira’s falling value and their dependence on imports for nearly all inputs to generate electricity.

These conditions are not unique to Aleppo. Long bread and fuel lines are regular sights in Damascus and many other cities, and similar shortages of electricity are common throughout the country.

Militias and security forces dominate daily life and compete with one another in other places as well. Iran-backed militias jostle with regime security forces in Deir al-Zor, for example, and a May 2021 dispute over grain profits between an NDF leader and security force members in the Hama countryside led the latter to burn acres of crops. The armed actors’ predation is less severe in areas that never fell out of regime control, but it is not entirely absent. In the Damascus suburb of Jaramana, for example, the government removed checkpoints that were sources of illegal profit for security forces in early 2019, but militias and security officers are still extracting duties on trade, particularly in construction materials.

B. Barriers to Return

The difficult living conditions and predation discussed in the preceding sections make return impossible or very unattractive for many Aleppo residents who were displaced by war. Nonetheless, some people have returned to the city’s east (see Figure 3), primarily from other regime-controlled areas of Syria. The eastern neighbourhoods’ population fell from 1.3 million in 2004 to 220,000 in January 2017, when the regime retook them; approximately 310,000 residents have since returned. By contrast, the population of the central neighbourhoods rose from about 350,000 in 2004 to 545,000 in January 2017. Since this area never fell out of regime control, it experienced far less displacement and acted as a refuge for many residents fleeing violence. Only 26,000 former residents have returned since 2017. The population of the old quarters in the middle of the city fell from about 405,000 in 2004 to 300,000 in January 2017 and has since risen by about 80,000.

But return is dangerous for the majority of Aleppo’s displaced, who during the war moved to Turkey or to Idlib and other rebel-controlled areas of the north west. The mere fact of having lived outside regime-controlled areas exposes returnees to suspicion of sympathising with, aiding or actively participating in rebel activities. This suspicion can be pretext for arrest or exploitation. Returnees from opposition areas may be apprehended for alleged opposition activity or avoiding mandatory military service. Police may detain others simply to extract a ransom payment.

The regime has created a mechanism to facilitate reconciliation and return, dubbed “settlement of security status” (taswiyat al-wadaa al-amni), but it inspires little confidence. The process involves a formal clearance with each of the four major security agencies and a verification that the person in question has satisfied all mandatory military service requirements.

Individuals report, however, that going through it has put them at greater risk of detention and extortion in subsequent interactions with security officers. A mukhtar and former Baath official in eastern Aleppo recalled that security forces regularly enquire about youths who have undergone these reconciliation processes, in order to “invite” them to “visit” the security branch, where they are then rearrested. Many disappear.

Even basic civil registry documents can complicate return. The regime does not recognise marriage, birth or death records made by opposition or Autonomous Administration authorities, pushing many displaced Aleppans to remain outside regime-controlled areas. Others may have to go through strange contortions. One couple, who married while displaced to an opposition-controlled area, where they had a child, returned to Aleppo two years later and registered themselves as “just married”. Nine months later, they registered their two-year-old as a newborn.

Displacement dynamics are also at play between Aleppo’s eastern and western neighbourhoods. Those who remained in the destroyed eastern part after regime recapture were primarily poor and/or elderly – those who lacked the means to get out or who feared the unknown more than staying.

Many former residents of the east, now displaced to the city’s west, have exhausted their savings and depend on remittances to pay rent in flats across town in the west, which was far less heavily destroyed and has better security and public services.

The migration of eastern Aleppo residents and non-Aleppans to the city’s west during and after the fighting has accentuated pre-2011 identity divides and contributed to the inversion of the city’s hierarchy of power.

The dominant economic actors in Aleppo today are primarily traders and militia leaders who have established themselves during the last decade and lack generational roots in the city. As indicated above, many generational residents resent what they feel is a loss of ownership of the city and hold a grudge against residents with roots in the countryside, even though most of these people have suffered similar harm from war and predation.

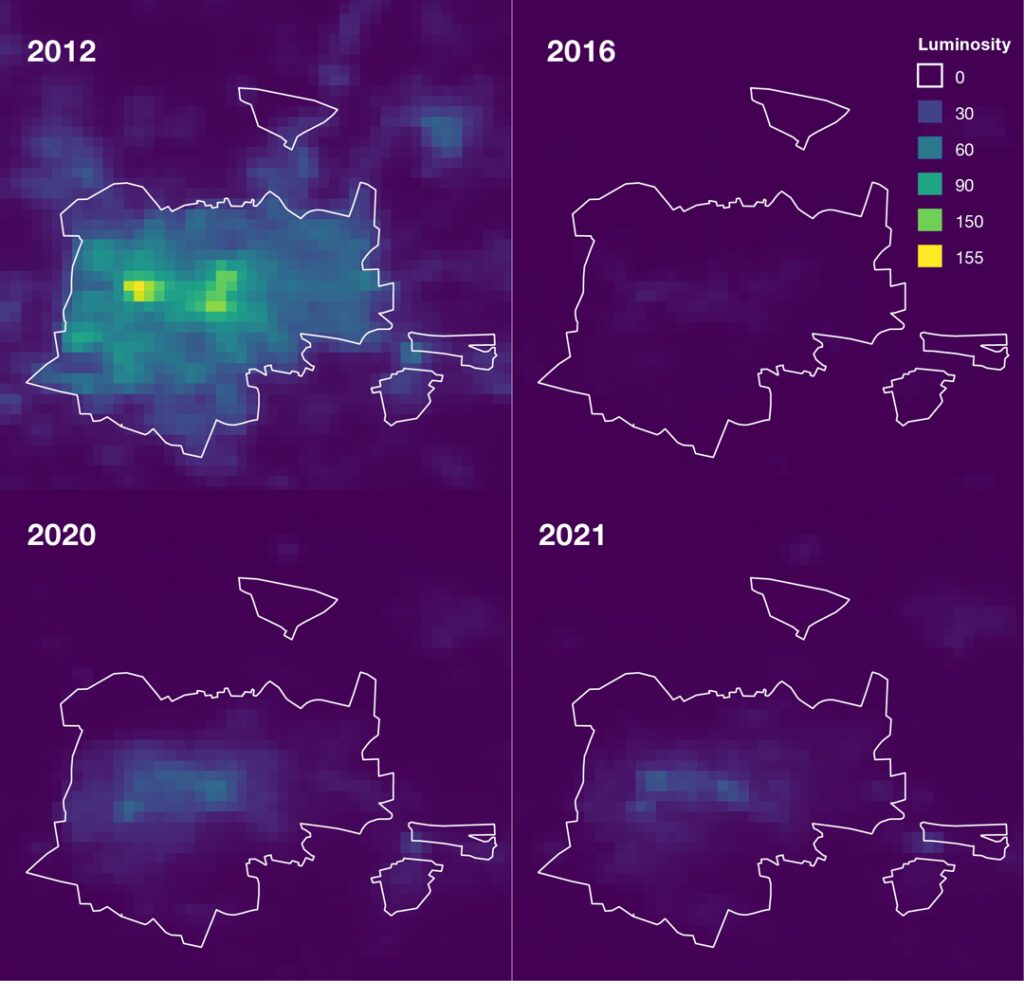

Satellite imagery of night-time light emissions starkly illuminates the divide between east and west, both during and after war (Figure 4). The picture dated April 2012 represents the last days before fighting engulfed Aleppo, when light is visible in all parts of the city. By 2016, the city has gone nearly dark. Light slowly begins to return in 2020, particularly in western neighbourhoods, but it falls again in 2021, likely due to the declining ability of the government and private generator operators to produce electricity.

This series of images demonstrates not only how little electrification the east has had, but also the disproportionate return to western neighbourhoods.

C. Business in the New Order

War destroyed the warehouses, dispersed the workers and shattered the supply chains of Aleppo’s industrial and trading families, which ran Aleppo’s pre-war economy. The largest industrial producers mostly moved their operations abroad, primarily to Turkey and Egypt.

While some industrialists retain a limited, often symbolic presence in Aleppo, so as to be able to scale up once conditions improve, many lack the resources to do so. Smaller workshops, however, have sprung back into operation, with individual artisans making products like shoes and wooden furniture by hand. Many of these workshops are set up by migrants in residential neighbourhoods rather than by established businesspeople in industrial zones.

Security tops the list of obstacles to business returns. Many entrepreneurs, whose livelihoods were not dependent upon state largesse and who disliked the regime’s arbitrary and violent rule, supported the opposition and now face the scrutiny security agencies apply to all Aleppans returning from outside regime-controlled areas.

Another problem for industrialists is the labour shortage. Many skilled labourers joined the opposition, or have extended family members who did, and hence they fear being caught in the security agencies’ dragnet should they return to Aleppo. Even unskilled youths with no opposition links are wary of working in the city due to the threat of conscription.

Most labourers in factories are either teenagers or men over 45 (the age range for mandatory conscription being 18 to 42). With so few men available, one construction contractor said he has begun to depend more heavily on female workers.

Operational difficulties are a third deterrent to investment. Unreliable electricity supplies from the public grid mean costly outages and expensive outlays for private generators, as described above. Inflation has wiped out capital belonging to small traders and industrialists, who held savings in Syria, making it impossible for them to purchase new products and capital equipment from abroad.

Even those who hold capital outside the country face difficulties importing the spare parts and supplies needed to make the products in which Aleppo specialised, such as textiles and plastics. Industrialists must smuggle these goods in through Lebanon or Turkey, forcing them to pay multiples of what they would have paid before 2011. Most older businesses that remain are engaged in small-scale industry, such as clothing production, woodworking and basic metalwork. Bribes extracted by state officials and protection duties (atawat) imposed by militias and security forces add to everyone’s operating costs, whether traders, industrialists or even small vendors in Aleppo’s markets.

New businesses opened by entrepreneurs who established themselves during and after the war are far simpler and less productive than those common in pre-war Aleppo. They focus primarily on services, including restaurants, coffee shops, fast-food outlets and bakeries.

The most successful ones rely on militia and security agency connections to smuggle in fuel and Turkish goods, which wealthy Syrians prefer to Chinese or Syrian products.

These new, militia-connected economic actors are sidelining the old elite. This dynamic was visible in a June 2020 conflict between Fares Shehabi, a prominent businessman before 2011, and Khudr Ali Tahir, a former chicken seller from Tartus, who commanded a militia close to the 4th Division during the war and now runs companies involved in cross-border trade and smuggling, as well as a security force protecting Iranian pilgrims.

Following accusations from Shehabi broadcast on state television that Tahir destroyed the Aleppo plastics industry by flooding the market with illegal imports, the interior ministry banned state institutions from working with Tahir. Tahir, however, used his regime connections to get the decision overturned and the Shehabi interview footage removed from the state television channel’s website.

State officials are also involved in predation on established entrepreneurs, as demonstrated by an agreement between the Aleppo Chamber of Commerce and the Syrian Customs Directorate. In late December 2020, customs officials confiscated large amounts of goods from established Aleppo traders and moved to close the central market on the grounds that traders had evaded customs duties. The traders retorted that customs officers were trying to extract bribes on top of payments they receive from warlords to allow the warlords to flood the market with goods smuggled from Turkey. The dispute led to meetings of the Chamber of Commerce, the Customs Directorate and security agencies, which defined the terms under which customs officials could enter the market and made the Chamber the mediator between the Directorate and individual traders.

” The overall effect of competition from warlords and predation by officials is that many remaining traders cease operations or move to Damascus or abroad. “

This mediation proved ineffective in reducing predation. Seizure of goods and demands for bribes by the Customs Directorate and other security agencies continued throughout 2021, prompting traders in Aleppo’s markets to go on strike in August.

The overall effect of competition from warlords and predation by officials is that many remaining traders cease operations or move to Damascus or abroad. The traders’ discontent reached the point that Industry Minister Ziad Sabbagh travelled to Aleppo in December 2021 to reassure them that Damascus would amend rules governing import of foreign textiles to protect domestic production. Yet he took no specific action in this regard, frustrating the traders further.

D. Home Demolitions and Expropriation

Housing is a crucial field in the struggle to shape Aleppo’s future. The city’s eastern part, site of the most physical destruction, has seen little rebuilding. On the contrary, authorities have undone repairs made by residents, sending municipal work crews to demolish newly refurbished parts of buildings, to further their own control over who returns to the area.

Militias loyal to the regime are intervening in many eastern neighbourhoods to serve their purposes, expropriating houses or pressing residents to sell properties at below-market rates, taking over trade in building materials and distributing housing to their fighters. By controlling who is able to live in these areas, militias bolster support for the regime, while reaping profits.

Residents of damaged eastern Aleppo neighbourhoods face enormous challenges in keeping buildings habitable. Building collapses occur several times a year.

A 2019 study by the government’s Public Company for Studies and Technical Consultations found 10,000 buildings that were likely to fall down and recommended that 4,000 families immediately evacuate. The study’s scope did not include informal neighbourhoods, the most heavily damaged during fighting. Another study from 2019, by the Governorate Council, estimated that 70 per cent of buildings in eastern Aleppo were damaged and that 30 per cent would need repairs before anyone could move back in. Yet many of these buildings are still inhabited.

” The state has invested little in reconstruction … residents themselves usually do – and pay for – what little repair work is done. “

The state has invested little in reconstruction. It has cleared many eastern Aleppo neighbourhoods of rubble, but these areas are usually abandoned, and militias and security services move in to scavenge for loot among what is left.

Residents themselves usually do – and pay for – what little repair work is done. In many eastern Aleppo areas, the mukhtar and notables collect money from shop owners and residents, and coordinate with government engineers and labourers to buy materials and make repairs. Building materials, however, are a major target for extortion, as security forces and militias impose their own informal duties on traders bringing these items into the city.

Residents of heavily damaged areas also confront legal and bureaucratic barriers to repairing their homes. In practice, only those with the ear of power –security forces or militias – can secure informal permission to make repairs. An Aleppo City Council decree lays out a formal registration process for refurbishing damaged buildings. Yet this process is available only to people in the city’s formally built areas and entails documenting a property’s formal ownership and paying a “damage licence” fee – not to mention bribes to government employees.

Most destroyed areas are outside the formal city plan – and thus not eligible for licencing – and their owners lack the required land tenure documentation. Moreover, new national legislation gives authorities in Damascus power to expropriate areas destroyed in war.

Residents attempting to rebuild without official permission risk home demolition by authorities.

All construction outside the city’s formally zoned areas is considered illegal. Technically, authorities can order any such building demolished, though they have tolerated large amounts of informal construction over decades of rural-to-urban migration. A 2012 declaration laid out procedures for formalising previous illegal construction and harsher penalties for that carried out subsequently. Yet post-2012 construction is hardly distinguishable from other illegal or even legal work, particularly in areas heavily damaged by war. In practice, it is only residents without ties to security services or militias whose houses are subject to demolition, regardless of when they built the dwellings.

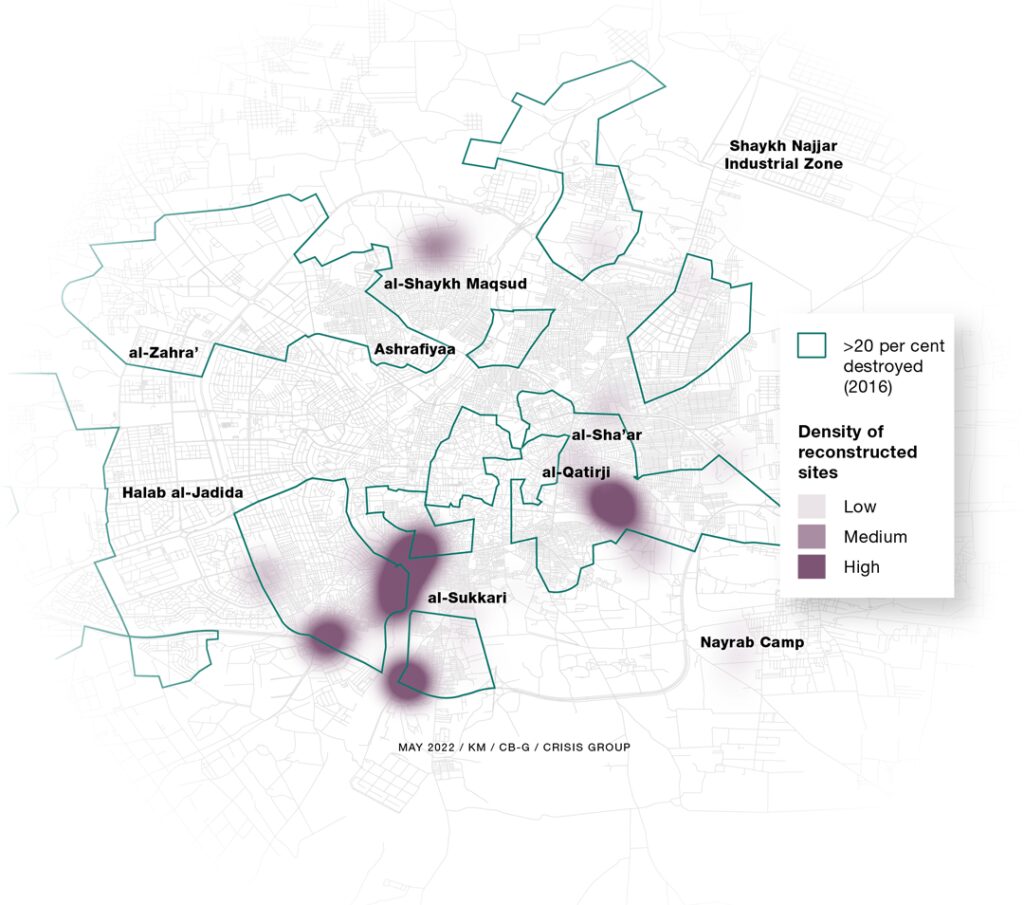

Rebuilding is concentrated in the spontaneously settled areas to the city’s east and south. To better understand the spatial distribution of actors able to flout formal building rules, Crisis Group made a map of where reconstruction is occurring, using high-resolution satellite imagery of Aleppo.

Figure 5 charts the reconstruction that occurred between September 2020 and January 2021, the period in which it began to pick up. Reconstruction in informal areas is concentrated in areas that experienced high levels of destruction. It is not evenly distributed in heavily destroyed areas but appears primarily in districts, such as al-Sukkari and al-Qatirji, run by regime-allied militias. By contrast, there has been little reconstruction in the old city, which was on the front line of regime-rebel fighting, or the Kurdish-majority neighbourhoods to the north east, Ashrafiya and Sheikh Maqsoud. The reasons stem from relations between local armed actors and the regime. The PYD and other cadres dominating the latter two neighbourhoods are far more ambivalent about the regime than the militias in the city’s east.

On top of the challenge of rebuilding, residents of Aleppo face the threat of property seizure by militias. Leaders of militias have repeatedly expelled residents from their flats on the pretext that the owner supports opposition activists or insurgents, or that his sons are fighting alongside them. Where militias do not seize properties outright, real estate agents connected to them use the threat of expropriation or security service intervention to press residents into selling at a price below market rate.

Regime-linked entrepreneurs are positioning themselves in the city’s eastern areas for the long term. A company called Qatirji for Real Estate Development and Investment has been buying properties that agents allegedly seized from their original owners, many of which are in eastern Aleppo near a major highway.

Since many of these properties are uninhabitable, many residents speculate that the government has a plan for total demolition and centrally planned redevelopment – at their expense. Similarly, subsidiaries of Qatirji Holding Group are doing restoration work in Aleppo’s old city and numerous other neighbourhoods. They have created an industrial area to produce the needed building materials.

IV. What is to Be Done?

After Syrian security forces and regime-allied militias recaptured Aleppo from rebels in 2016 and 2017, they plundered a city already heavily destroyed in war (primarily by the regime and its allies). Socio-economic life in Aleppo today is dominated by the predation of state security forces and non-state militias tied to Damascus and its backers, Iran and Russia. Because these actors drive away the capital and labour needed to restart large-scale trade and production, their predation virtually guarantees continued stagnation in what was Syria’s economic dynamo.

Aleppo’s present governance has displaced and alienated the city’s former entrepreneurial classes. Many have voted with their feet, taking their families and business operations out of the country.

Others have stayed but registered vocal complaints; businessman Fares Shehabi, for example, has repeatedly denounced the protection money importers must pay to militias and security agencies. Muhannad Daadush, head of the textiles sector of the Damascus Chamber of Industry, recently enumerated the problems faced by entrepreneurs: the list includes an inconsistent, expensive electricity supply, persistent insecurity that makes it difficult to bring potential purchasers of Syrian goods to see what they would be buying, and the difficulty of obtaining specialised imports.

This bleak picture of Aleppo comes against an equally dispiriting broader Syrian political backdrop. There is virtually no prospect of genuine progress toward the political transition envisioned in UN Security Council Resolution 2254 that could clear the way for the external assistance and investments needed for a comprehensive reconstruction effort. A return to pre-war security and prosperity seems impossible to imagine at present. What, then, can be done to ameliorate living and business conditions in Aleppo and other areas of regime-controlled Syria?

Major reconstruction support – in the form of grants from donor countries and loans from international institutions for projects like rebuilding the power grid – is not on the table. Nor is the EU’s “more for more” plan, proposed in 2017, that conditions broader relief on concrete action by Damascus. There is little appetite for either in Western capitals, with the U.S. and E3 standing by UN Security Council Resolution 2254. Indeed, recent experience has revealed the infeasibility of reconstruction plans. Internationally, the Geneva peace process has sputtered, due partly to the regime’s intransigence – even rebuffing demands from its ally, Russia. In Syria, militias and security agencies prey on civilians and the regime does not follow through on its promises of reconciliation with those who stood against it. The informal governance that prevails virtually guarantees that large amounts of aid will be diverted; the constellation of regime and regime-affiliated actors in the city are likely to swallow up any such assistance, meaning that it will do little to encourage the return of residents and businesses.

” The experience of Aleppo suggests that the regime … is gravitating toward a patchwork of territorial control propped up by warlords-turned-entrepreneurs. “

The experience of Aleppo suggests that the regime, rather than bringing back the highly centralised pre-war patronage patterns, is gravitating toward a patchwork of territorial control propped up by warlords-turned-entrepreneurs. Whether this approach is a strategic choice or an opportunistic reaction to the regime’s diminished power is unclear. What is clear, however, is that after years of latitude in the city, militias are entrenched to the point that no single edict from Damascus – much less one from outside powers – can root them out. Aspects of militia rule have been incorporated into state institutions and wartime tycoons have become deeply integrated into parts of the Aleppan economy.

If this political context rules out large-scale loans and aid, it makes humanitarian aid – including “early recovery” activities like small-scale rehabilitation projects – all the more critical for ameliorating Syrians’ suffering. In this vein, the U.S. Treasury Department in November 2021 signalled openness to activities like repairing schools and refurbishing mills, silos, and bakeries.

Though meagre compared to the scale of the need, such aid, which represents the outer limit of what donors can provide with any confidence that it will contribute to restoring the city’s socio-economic life rather than profiting the predatory few, is essential.

Still, expectations should be realistic about what it can accomplish – both for beneficiaries and in political terms. Early recovery projects now getting under way will provide more than the immediate sustenance of humanitarian aid, but not enough to address the basic infrastructural needs to make businesses viable and give city residents a degree of normalcy. Rebuilding a grain mill or bakery, for example, will remove a central barrier to a local community producing bread locally, which can make a difference to local Syrians’ lives. But with the public electricity grid in tatters and international funding for repairing it out of the question, that same bakery will remain short on consistent, cheap electricity, and thus vulnerable to interruptions in production and forced to pass on the high costs of generator electricity to their struggling customers. Nor will these small amounts of early recovery aid alter the basic state of predation prevailing in Aleppo at present and in Syria more generally.

A sober view of the limits to what Western states and international institutions can achieve also refocuses attention on the interests and abilities of actors on the ground, chief among them, the regime in Damascus. There is a tendency among analysts and Western policymakers to think about the regime in binary terms – it either has control over an area or it does not; it is a reliable partner or it is not. reality on the ground, however, presents a far more nuanced picture of what passes for “government control”: the regime has not ceded authority completely to competing militias, but neither can it eject them entirely from the hierarchy of power. Though it repeatedly fails to honour commitments made in negotiations in Geneva, the regime can still take steps that would foster conditions more conducive to socio-economic recovery, boosted by foreign assistance. Indeed, it has a history of slowly bringing informal armed actors under control, giving them tacit licence to smuggle and extort, and reining them in when they overstep their bounds.

Damascus could take incremental steps similar to those it has taken in the past to curb predation by militias and state security agencies in Aleppo. Redeploying some militias to sites outside the city could have been a step in the right direction, but it has yielded little improvement, as the state agencies engage in the same behaviour. The problem lies less in whether the armed groups are affiliated with the state or a non-state entity, and more in what orders they receive and who, if anyone, is holding them accountable.

” Russia and Iran … can press militia leaders to stop extorting businesses and abusing civilians. “

The regime’s external allies could help. Russia and Iran may not be able or willing to strong-arm the regime into taking specific action, but they can press militia leaders to stop extorting businesses and abusing civilians. They exert such influence already as opportunities arise, such as when militias allied with one foreign backer to coordinate their activities; they could mount a similar sustained effort against predation.

Such action would also serve both states’ interests, as each has expressed a desire to foster economic recovery in Syria. To the extent that China, which has included Syria in its Belt and Road Initiative and identified Aleppo as a prospective site for investment, begins to put money into the Syrian economy, it might also use whatever leverage it has to convince the regime to curb militia abuses.

V. Conclusion

The issues facing displaced Aleppans and current residents crop up in much of regime-controlled Syria: predation by militias and security agents alike on average citizens, nearly non-existent public services, and unpredictable but severe punishment for anyone suspected of having supported the opposition. Meeting basic needs, not to mention rebuilding neighbourhoods and reopening businesses, is a struggle under these conditions. What makes the situation in Aleppo particularly painful is that the city was the economic engine of pre-2011 Syria. The city’s domination by militias and businessmen who have arisen during the war comes at the cost of hurting established entrepreneurs and other Aleppans – and even the regime itself. After all, revived productive economic activity would provide much-needed revenue and go some way toward lessening the grievances of citizens living under the regime’s rule.

The regime’s unwillingness or inability to curb the opportunistic, exploitative actions of its security forces, let alone quasi-independent militias, operating in Aleppo suggests a grim future for the city and other territories under the regime’s thumb. Absent a concerted effort by central authorities to limit this predation and encourage the return of traders and producers to former economic centres like Aleppo, regime-controlled Syria is set to remain a mosaic of competing fiefdoms that thrive on the misery of war-weary and disempowered populations.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News