The War in Ukraine Should Prompt a New Opening to China

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and the responses of the United States and China—has generated the first great-power crisis in decades. Such crises are rare and terrifying, especially in the nuclear age. Understandably, therefore, countries go to great lengths to avoid them. But great-power crises can produce an unexpected benefit: insight into the balance of power among states, as well as their interests and resolve. Acting as a truth teller for world politics, crises undermine myths, expose weaknesses, and surface underlying strengths. They force countries and their leaders to interrogate long-held policies and update their postures based on new realities. A country that believes its position is excellent might discover that it is in fact exposed or overextended, and a less confident country might discover underappreciated strengths.

Great-power crises also promise something else: the opportunity for states that come out on top to reorder global relations in ways that provide long-term stability. This outcome is not automatic or even likely. Crises are dangerous, uncertain, and easily devolve into deeper confrontations. But through enlightened statesmanship, savvy diplomacy, and strategic patience, it is possible for “winning” states to reshape the global order to their advantage without humiliating their adversaries. The United States did this after the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, when U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s administration emerged looking both stronger and more resolute than the Soviets but did not push its advantage, instead planting the seeds of détente. Now, the United States has the opportunity to do so again in the aftermath of the crisis in Ukraine.

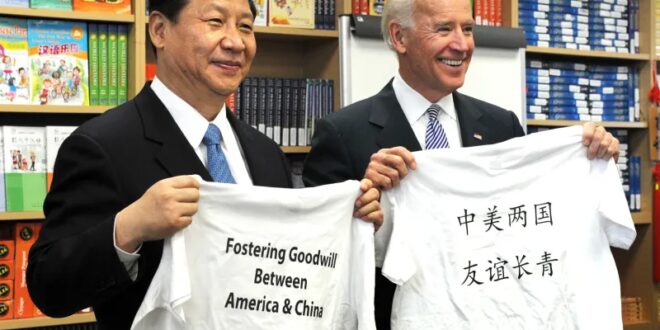

Russia’s war has starkly, if surprisingly, demonstrated that Washington’s standing in the world is stronger than previously assumed. Moscow’s flaws have been exposed. Perhaps more consequentially, the crisis has revealed that China’s position vis-à-vis the United States is weaker than many thought. U.S. President Joe Biden will be tempted to exploit these newfound advantages—to draw attention to Chinese problems and highlight American advantages. He should resist that temptation, recognize that China isn’t Russia, and quietly explore whether new global realities allow for a mutually beneficial accommodation with China.

Skeptics will reasonably counter that accommodation is unwise. China has not softened its rhetoric nor condemned Russia’s war. It has demonstrated scant interest in compromise, especially over the most contentious and dangerous of issues: Taiwan. Accommodation might require the United States to de-emphasize important priorities such as human rights. It could generate understandable consternation among U.S. allies and outrage domestically. The best an accommodation could achieve, moreover, is a seemingly desultory goal: a return to where U.S.-Chinese relations were at the start of the twenty-first century, when both countries committed to avoid great-power war despite fundamental disagreements.

The United States must therefore be clear-eyed about what this strategy can and cannot accomplish. It cannot make a friend or an ally of China, a country whose ideology and ambitions guarantee some level of competition or rivalry with the United States. But it can do something even more important: avoid the looming catastrophe of a direct war between superpowers and possibly create the conditions for limited cooperation on pressing global issues, such as climate change, nuclear proliferation, and pandemics. Simply seeking to deter China without endeavoring to engage it is an uncertain and dangerous strategy. Washington should seize the opportunity created by the crisis in Ukraine to chart a safer and more prudent path.

BRAVE NEW WORLD

The world looks much different today than it did on February 23, 2022. Prior to its invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s conventional military, backed by the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, appeared invincible. Moscow controlled enormous energy resources needed by much of the world and possessed cybertools and disinformation capabilities that many thought were unparalleled. Russia received warm support from a powerful and focused China, whose increasing economic and political strength seemed magnified by its successful COVID-19 policies.

The United States, by contrast, looked feckless after its ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan. Its European allies appeared fractious and unprepared to meaningfully contribute to their own security. Washington’s effort to deter Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion failed, and few believed U.S. sanctions would be widely embraced or effective. The liberal order and its ineffectual institutions seemed broken, and authoritarian countries seemed ascendant, better suited to generate power and exploit the weaknesses of democracies to shape the international system.

Fast forward to today, and things look quite different. Although Russia remains a leading nuclear power, its military has been exposed as overrated, its cybertools and disinformation weapons have been blunted, and its long-term economic future appears bleak. The United States and its allies agreed to a far tougher sanctions package than most analysts expected, supplemented by increasingly large and lethal arms shipments to Ukraine. NATO is more unified than ever and could be about to welcome Finland and Sweden as new members, a once unthinkable prospect. Even the global narrative about democracy and dictatorship has shifted: countries that had been unwilling to embrace the Biden administration’s adversarial framework, such as Germany and New Zealand, now seem open to accepting this approach.

With Russia weakened and Europe more committed to its own defense, Washington can now focus its growing military capabilities on China.

The crisis has also cemented the U.S. dollar’s central place in the global economic system and demonstrated the extraordinary market power of American financial and technology companies. With Russia weakened and Europe more committed to its own defense, moreover, Washington can now focus its growing military capabilities on China, whose economic, technological, and public health record seems less impressive than it did even a year ago. The United States and three other democracies with vibrant economies—Australia, India, and Japan—have strengthened their association through the Quad, while the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s signature act of global statecraft, has dramatically underperformed.

But the war in Ukraine hasn’t just revealed unexpected American strengths; it has also exposed Chinese vulnerabilities. China’s association with and unwillingness to criticize Russian brutality has harmed its global reputation. Moreover, Russia’s military setbacks have forced Chinese military planners to question whether a cross-strait invasion of Taiwan—a more difficult military goal than conquering Ukraine against an arguably harder and better-armed adversary—is plausible. And even if China were to succeed in taking Taiwan by force, its reward—like Russia’s—might be a full-scale policy of containment by the West, economic and technological decoupling, and exclusion from the international system.

THE CASE FOR ACCOMMODATION

Given these dramatic shifts, why should Washington seek accommodation with Beijing, and why would Beijing be interested? Skepticism is warranted. Any overt U.S. effort to suggest that changing global circumstances allow for a new approach to China could alarm Beijing, generate sharp domestic backlash, and confuse U.S. allies. Critics of accommodation, moreover, might be right that the structure of the international system and the nature of each power’s regime mean that confrontation and conflict between the world’s leading powers is unavoidable.

But the critics of accommodation must ask themselves how confident they are in the alternative. Currently, Washington has no long-term strategy for dealing with Beijing aside from deterrence. Will this strategy—which failed against a far weaker Russia—succeed against China, and what cost should the United States be prepared to pay if it does not? Deterrence works less well without assurances, and it often succeeds only in buying time. As a strategy, it tells countries what to avoid but says little about where to go or what they should be prepared to live with—core elements of any good grand strategy in a world of competing interests.

Simply seeking to deter China without endeavoring to engage it is an uncertain and dangerous strategy.

Focusing solely on deterrence also risks further escalating tensions between the United States and China. Bilateral relations have already deteriorated to such an extent that conflict is increasingly seen as inevitable in both countries. Short of war—which would be far more ruinous than the current conflict in Ukraine—poor U.S.-Chinese relations risk further undermining the international order. The calamitous COVID-19 pandemic, which has killed upward of 15 million people, shows what can happen when the world’s two leading powers fail to cooperate. A new U.S.-Chinese understanding, focusing narrowly on shared interests and concerns, might help both powers prepare for and respond to the next global crisis.

And there are reasons to think Beijing may be open to such an understanding. Unlike Russia, China has a dynamic economy and an impressive technological base, both of which would suffer from further decoupling from global markets. Beijing has also shown more interest in engaging with and even supporting elements of a rules-based order than Russia has. China may be feared, but unlike Russia, it is also admired in many capitals.

Washington may pay a political price for pursuing accommodation, but it is unlikely to pay a strategic price. Generosity during a period of strength may achieve better results than continued confrontation in the face of uncertainty about the future balance of power. If a sincere U.S. effort at accommodation fails, moreover, it will remove all doubt about China’s intentions, helping persuade fence-sitting countries to support a U.S. shift to a more vigorous economic, political, and military strategy to counter Chinese belligerence.

BACK FROM THE BRINK

This would not be the first time the United States parlayed the clarifying effects of a great-power crisis into more stable relations with an adversary. Like the current crisis, the Cuban missile crisis altered the world’s perception of the international system, revealing the United States’ power and resolve to be stronger—and the Soviets’ to be weaker—than previously thought. Prior to the crisis, the Bay of Pigs fiasco, a humiliating summit between Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, and the disarray of the Western alliance had made the Kennedy administration seem weak. The Soviets, by contrast, appeared to be made of steel, with the forces of history on their side.

All that changed after 13 days of threats and back-channel diplomacy, when Khrushchev acceded to Kennedy’s demand that the Soviets remove nuclear-tipped missiles from Cuba. Although Washington publicly promised not to invade the island and privately agreed to remove similar missiles from Turkey, the outcome was seen as a victory for the United States. The view in capitals around the world—including in Moscow—was that the balance of power, interests, and resolve now decisively favored the United States.

But instead of exploiting this newfound strength to take a harder line against the Soviet Union, Kennedy chose the more difficult, politically risky but ultimately more productive path—a political accommodation. This was not an easy task. He had to sideline hawks within his administration, including military leaders; win over Congress; and push back against recalcitrant allies, including French President Charles de Gaulle and West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. Kennedy understood that the Soviet Union was an aggressive authoritarian state bent on challenging American values and interests around the world. But he also understood that the Soviet Union wasn’t going away any time soon, that many of its political interests had to be acknowledged as legitimate, and that the dangers of the nuclear age obligated him to minimize the possibility of great-power war. Critically, he grasped that the two powers shared an interest in stabilizing the international system and preventing other states from acquiring nuclear weapons.

In a nuclear world, Kennedy recognized that his greatest obligation was to seek peace.

After months of quiet diplomacy, Kennedy signaled the reorientation of U.S. strategy in a speech at American University in June 1963. The president, who just two years earlier had promised that the United States would “pay any price” to “assure the survival and success of liberty,” now argued that if Washington and Moscow cannot end “our differences, at least we can make the world safe for diversity.” The speech had its intended effect, and the previously recalcitrant Soviets became more open to negotiations. According to Khrushchev, Kennedy’s address was the “best statement made by any President since Roosevelt.”

Kennedy built on this goodwill by sending Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Averell Harriman, who was well regarded by the Kremlin, to Moscow to discuss efforts to limit nuclear proliferation. Kennedy empowered his emissary to tell the Soviet leadership that he sought a broad understanding that would avoid great-power war. The goal was not to resolve long-standing differences—such as the political status of Germany and Berlin, which had nearly led to war—but rather to agree to put those issues “on ice.”

These extraordinary efforts produced what the historian Marc Trachtenberg has called “a constructed peace.” The Cold War did not end in 1963, but the risk of nuclear war was dramatically reduced. Kennedy’s diplomacy laid the foundations for the landmark 1968 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and for the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which stabilized great-power politics and dramatically reduced the risk of conflict. And although this détente unraveled for a time in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Cold War never again brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

THE NUCLEAR BURDEN

This history offers lessons for how the Biden administration might pursue an accommodation with China. First, it would have to develop a strategy to deal with the political costs of an effort that will be unpopular with many and that may not succeed. That would mean winning over key members of Congress, persuasively making the case to the larger public, and intensively reassuring allies. Second, the administration must discreetly find an interlocutor who both speaks for the president and is well respected in Beijing. It is difficult to imagine the national security adviser sneaking off to Beijing undetected, as Henry Kissinger did over half a century ago. But a former diplomat or a figure from the private sector might be quietly dispatched without attracting public attention.

Third, the administration would have to be realistic about what it can achieve. The goal for Taiwan, as it was for Berlin and Germany in 1963, cannot be to achieve an elusive resolution. It must be to put the issue on ice and push it off into the future. This would require both sides to stand down from recent efforts that risk humiliating the other or escalating to war. Although fragile, this formula has kept the peace in the Taiwan Strait for four decades. Finally, a policy of accommodation would require Washington to pay the high price of de-emphasizing important concerns, such as China’s terrible human rights record. As Kennedy observed, “we must deal with the world as it is.”

There is no guarantee that China would respond positively to such a gesture. Beijing may not think the balance of power has shifted in the United States’ favor. Or worse, it may think the balance of power has shifted so dramatically that it must move against Taiwan now or forever lose its chance. Biden will have to bet that Chinese leaders see what he sees: a stronger United States flanked by reinvigorated allies, a weakened cast of authoritarian powers, and a potentially enormous downside to deepening rivalry. Should he pursue the path of accommodation, the odds of success will be long—but no longer than those Kennedy faced in 1963. Back then, relations between superpowers were far worse, the geopolitical and ideological divisions between them were much deeper, and the issues were equally irreconcilable. In a nuclear world, however, Kennedy recognized that his greatest obligation was to seek peace. Biden must do the same.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News