On 29 May 2022, Colombia held the first round of its presidential elections, with a little over 50 percent voter turnout. Since no candidate managed to secure the required 50 percent plus one mandate in the second round, the run-off election was held on 19 June 2022. The two candidates who received the highest number of votes and moved on to the second round of elections were, Gustavo Petro, a left-wing Senator and a former guerrilla fighter, and Rodolfo Hernández, a real estate tycoon, running as an independent candidate. Petro managed to secure over 40 percent of the votes, whilst Hernandez secured 28 percent in this round.

The run-off elections ended up making history in Colombia, with the country electing its first leftist President, Gustavo Petro. With 50.48 percent of the votes, he managed a narrow victory against Hernández’s 47.26 percent. To fully comprehend the importance of this year’s Colombian elections, it is important to put the political issues, its fragile internal security, and shaky external relations in the continent in perspective—all of which have fed into making this year’s presidential elections historical.

Presidents in Colombia are only allowed to serve for one 4-year term. Therefore, the incumbent President, Iván Duque Márquez, is not eligible to contest the elections this time around. A centre-right politician, lawyer and author, he came to power in 2018. One of his major planks while campaigning for his run was his stringent opposition to the peace agreement that was signed between the rebel group Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia or FARC, and the Colombian government. His objection to the deal stemmed from his belief that the rebels had been treated too leniently in the agreement and he would tackle this issue with priority, if elected. Therefore, his lackadaisical approach to implementation of the peace treaty attracted much flak from the citizens, especially given his government’s inability to protect former FARC rebels and even politicians and political activists from being killed. His government also disappointed Colombians with its inability to implement promised tax reforms and attract foreign investment. Amidst this growing dissatisfaction, the administration’s poor handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and an imprudent tax reform plan that would essentially squeeze the working and middle classes, the country saw wide-ranging protests and demonstrations against the government and its policies.

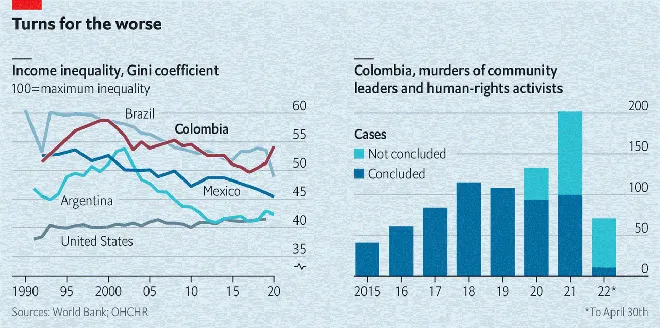

It is in this context that the current political climate and the presidential race in Colombia should be seen. Traditionally, Colombia has largely seen moderate politics with left-wing extremism being extremely unpopular in the country. Therefore, the fact that a left-wing former rebel has managed to secure the presidential seat is reflective of the fact that Colombians are now ready for change. Gustavo Petro had contested the presidential elections in 2018 but had lost to Duque in the runoff. As the runner-up, he got an automatic seat in the Senate. He has previously served as the Mayor of Bogotá. He has managed to form a coalition of the major left-wing parties in Colombia, called the Historic Pact. His running mate, Francia Márquez, an Afro-Colombian lawyer and environmental activist would become the country’s first Black-Colombian Vice-President if elected. Their campaign has largely focused on economic and environmental matters, along with a pledge to tax the rich, combat the income inequality in the country, reform the health care and pension systems, and tackle corruption. Petro strives to renew commitment to the peace deal with FARC as well.

Rodolfo Hernández Suárez, seen largely an outsider vis-à-vis Colombian politics, was running as an independent, on an anti-corruption platform, while facing charges of alleged corruption himself over a waste management scandal, during his tenure as Mayor of Bucaramanga in 2016. His quick rise in popularity has been a point of great interest in Colombia, given his tendency to avoid conventional forms of campaigning or forming political alliances. He has majorly used social media, particularly TikTok, even proclaiming himself to be the ‘King of TikTok’ to conduct his election campaigns. He has especially managed to reach many young voters. His impulsive, unconventional, and often crass means have driven comparisons of him with the former US President Donald Trump. His campaign slogan was ‘Don’t steal, don’t lie, don’t be lazy’. One of his proposals has been to ‘legalise cocaine’ in the country. Given the fact that he beat the conservative candidate, Federico Gutiérrez, who was backed by the current political establishment of Colombia speaks to the success of his unique ways.

Federico Gutiérrez was largely seen as the primary contender against Petro, up until he lost to Hernández in the 29 May elections this year. He was the leading conservative candidate, with support from a coalition of centre-right parties in Colombia. His policies largely revolved around being ‘tough on crimes’ and to restore law and order. He also campaigned on platforms of education reform, more skill-based training, fewer market regulations, and more state decentralisation in the country. Yet, given that he is also a conservative candidate, much of his policies were more or less an extension of the incumbent administration. As has been previously highlighted, the Colombian voters have been vying for change and therefore, it is principally this lack of substantial changes in Gutiérrez policies that led to his loss in the first round of elections. After the declaration of the results of the first round of elections, Gutiérrez announced his support for Hernández in the runoff.

In the run-up to the first round of elections, there were a total of eight candidates who had contested the Presidential elections. Other than the primary three contenders already mentioned, there was the independent candidate Íngrid Betancourt, the centre candidate Sergio Fajardo, the right-wing candidate Enrique Gómez Martínez, the independent candidate, Luis Pérez Gutiérrez, and finally the evangelical-affiliated John Milton Rodríguez. The race now, however, is only between Petro and Hernández.

The 2022 presidential elections in Colombia have proven to be unusual in several ways. A left-leaning candidate has the lead for the first time in the country’s history. The choice for the voters in the run-off was between two populist, anti-establishment candidates, both of whom were promising radical changes, an unprecedented choice in the hitherto moderate nation. The current round of elections also saw new priorities for the country. In the wake of the pandemic, economic issues like poverty, tax reform, health, and corruption issues have been at the centre stage and issues like the FARC peace deal have taken a lower priority.

The election of Gustavo Petro as President is symptomatic of a larger pattern in the Latin American region of left-leaning political leaders coming to power. Therefore, Chile, Peru, and Honduras saw leftist presidents coming to power in 2021. Petro is expected to renew the country’s commitment to the FARC peace deal, implement it on a priority basis, and seek negotiations with the still active ELN rebels. This becomes particularly important given Petro’s own history as a former guerrilla fighter a pertinent aspect.

With the results of the run-off elections declaring Petro as the President, Colombia’s relations with the United States (US) must be watched closely. He has been an outspoken critic of the US-led war on drugs and has advocated for a renegotiation of the US-Colombia trade deal which, according to him, has hurt the Colombian farmers and manufacturers. His campaign also included a proposal to restore diplomatic relations with its neighbour, Venezuela, with whom relations have been turbulent for the past few years. This could be another point of stress in the US-Colombia relations, which have been extremely strong under the now former President Iván Duque Márquez. The exact implications of the Colombian election results are yet to be seen by the world. However, what is certain is that the 2022 elections marked a historical moment for the country as it decided to shed its traditional approach to electing its leader and opting for a radical change instead.

As the graph above shows, over the past five decades Colombia’s internal security is in a state of flux, its income inequality high, and its rate of crimes consistently high—all these issues have posed unsolvable concerns for Colombian governments. Will the new left government in Colombia usher in a consequential change?

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News