Zuzana Čaputová, trust in whom has dropped precipitously over the past year, is under attack by politicians from all sides. Will she run again in 2024?

More than three years ago, Zuzana Čaputová, then just elected as Slovakia’s president, promised to be a president for all her country’s people.

“I have not come to rule Slovakia, but to serve its citizens,” the pro-European and pro-NATO leader said in her inauguration speech, stressing that she hoped to retain the public’s trust during her entire term of office.

Indeed, in 2019, Čaputová, then a new face in the political arena who ran on a promise to establish decency in Slovak politics, to bring people together and to speak up for the oft unheard, represented a positive change that most Slovak people were demanding a year after the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée. The shocking contract killing was one of the pivotal moments in her decision to run.

The experienced lawyer and committed environmentalist, compared to Erin Brockovich for her years-long fight against a toxic landfill in her hometown, grew up in a working-class family in Pezinok, a wine-making town near Bratislava. Three years ago, voters – liberals and conservatives alike – elected this empathetic, authentic and conflict-avoiding divorced mother of two as their first woman president.

Čaputová defeated the diplomat Maroš Šefčovič of the then long-governing Smer party, under whose rule corruption and organised crime had flourished.

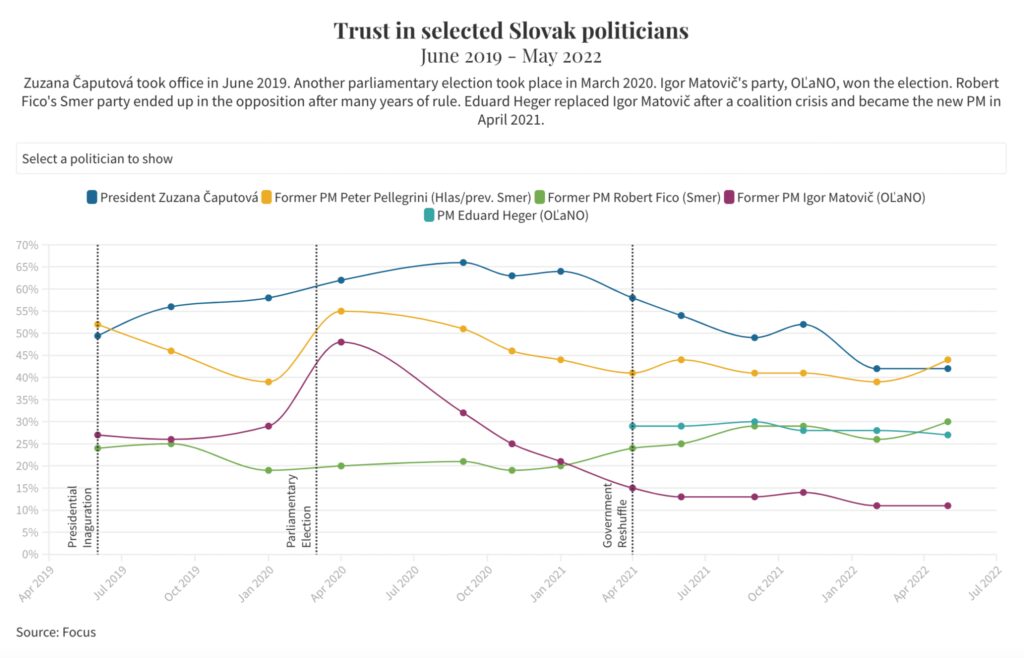

However, Čaputová’s popularity has been on the wane for more than a year now. Only 15 per cent of the electorate would “definitely” vote for her in the next presidential election due in April 2024, a poll in late May found; trust in her has fallen steadily from 64 per cent in January 2021 to 42 per cent in June.

The president took to Facebook on the third anniversary of her assuming office to admit she has struggled to balance two of her ambitions: to speak up when things go in the wrong direction while at the same time avoid getting drawn into conflicts that polarise society.

“Politics has taught me that I’ll always be dragged into conflict regardless of my efforts to keep out of it,” said Čaputová.

To understand how Čaputová is losing the trust of the public and how she might regain it ahead of a potential run for a second term in 2024, experts like Aneta Világi of Comenius University in Bratislava said it’s “necessary to look at the context in which the president has carried out her mandate.”

As president, Čaputová is not the one who submits bills to parliament nor does she enforce legislation, but she holds the right to veto legislation and turn to the Constitutional Court to assess its constitutionality.

The president is also not supposed to be a current member of any political party and thus non-partisan. Yet despite being consistent in terms of her promises and views during her term of office, including on the war in Ukraine, both coalition and opposition parties have managed to paint her as being politically partisan.

“Neither of the camps, however, speaks of her as their party’s president,” Világi pointed out.

Igor’s war of words

Igor Matovič, the finance minister and chair of Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO), the main coalition party, has been attacking the president since the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic. She did not shy away from pointing the finger at conflict-seeking Matovič, who was then prime minister, for his government’s lacklustre efforts to navigate the country through the health crisis.

“The whole world is coping with COVID-19, but we have to deal with the prime minister,” Čaputová, audibly emotional, said during a December 2020 radio interview.

It was the first time she had publicly criticised the then-prime minister. She called on Matovič a few months later to resign and end the coalition crisis ignited by his secret purchase of Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine.

Világi noted that the bitter vaccination debate in the country also contributed to rising distrust in Čaputová, one of the main faces of Slovakia’s vaccination campaign. Some members of the public suddenly identified her as part of a government that favoured the vaccinated over the unvaccinated, she added.

“Some people may also have felt disappointed by her outright, even militant support of vaccination and the associated more-or-less direct disparagement of the intellect of those who hesitated over getting vaccinated,” said Zuzana Kusá, a sociologist and Čaputová’s former social affairs advisor.

Vaccination, which became a highly politicised issue in Slovakia, has arguably polarised society more than anything else before it.

Matovič did not refrain from making attacks on Čaputová via Facebook, even after he was forced to step down last spring and became the finance minister in the cabinet of his successor Eduard Heger. More recently, he labelled her a “fake and insidious” woman.

When Čaputová announced in July that she would turn to the Constitutional Court over Matovič’s package of fiscal measures worth 1.2 billion euros – he describes it as a “family package” – after the coalition government overrode her veto with the help of far-right lawmakers in the parliament, the finance minister announced he felt ashamed of Slovakia having such an “anti-family” president.

Čaputová, for her part, described the government’s overriding of her veto in this particular case as “collaboration with fascism”.

Critical of lawmakers for passing the package without proper discussion, she defended her decision and said she wanted “families to receive targeted, timely and sufficiently effective help that Slovakia can afford.” She did not oppose the measures that were supposed to enter into force with immediate effect and help families impacted by surging prices, but Matovič has stuck to his version of events.

The finance minister and his package is the reason for yet another coalition crisis that continues to this day. Čaputová hinted on July 22 that Prime Minister Heger should consider dismissing Matovič, as has been demanded by one of the four coalition parties.

Opposition derides Čaputová as US agent

Both the opposition and even some in government believe the president is too close to the Americans. Matovič has accused her of plotting against the government with Bridget Brink, former US ambassador to Slovakia now serving in Ukraine, while several far-right and Smer lawmakers, including former premier Robert Fico, label her an American agent.

“The people who claim this know they’re lying,” the president said in February of this year.

The plot thickened in early 2022 when Slovakia signed and ratified a defence cooperation agreement with the US. Čaputová used her powers to attach an interpretation clause, a one-page document, to the agreement to dampen opposition-fuelled misinformation about it and to explain why the agreement would not result in the opening of US military bases nor allow the presence of US soldiers or nuclear weapons on Slovakian soil.

Another attack on the president came before last summer when the opposition accused her of trying to hamper a referendum on an early election. Smer submitted a petition with more than 600,000 signatures to Čaputová, but she decided to turn to the Constitutional Court, which ruled in the following weeks that the constitution at present does not allow for the term of a parliament to be shortened by a referendum, so a referendum asking such a question was deemed unconstitutional.

Smer is collecting signatures in another to attempt to force an early election referendum with different questions.

“The fact that I am being accused of thwarting the referendum [by Fico] is part of the fight for the character of this country,” the president said during a discussion at Pohoda, a music festival, on July 9.

Čaputová implied that political parties like Smer were trying to get elected as president a person who would serve their interests in the ongoing corruption investigations and court rulings linked to previous Smer-led governments. Another of the president’s powers: pardons.

A reluctance to attack her critics

Though Čaputová has generally turned a deaf ear to the threats and verbal attacks against her, she is well aware that some of the public has begun to believe the demonstrably untrue narratives circulating about her in the public sphere, especially on social media. According to a Globsec survey, Slovaks are particularly susceptible to disinformation and are prone to believing conspiracy theories.

“It’s undeniable that the opposition parties work non-stop to create and maintain the ‘anti-people’ picture of the president,” Kusá said.

In early September 2021, trust in the president dipped below 50 per cent for the first time since her election and has since continued to fall. At the same time, Robert Fico has managed to become one of the most trusted politicians again, even though in April he was charged with involvement in organised crime.

Almost a year later, in a June poll, after months of being the most trusted politician, she dropped into second place with 42 per cent behind the former prime minister and former Smer deputy chair Peter Pellegrini, despite her strong presence on social media and the widespread media coverage of her presidential activities.

“It’s not enough to just repel attacks on social media,” Világi underlined.

Instead, observers say, Čaputová needs to adopt the aggressive strategy of her opponents to gain the upper hand. Yet this would go against her intention to be more consensual and a less polarising figure. Moreover, a more forceful approach could harm her if she decides to run again in the next election in April 2024, especially during the campaign for it.

“A large number of Slovaks make their decision at the last minute,” Világi noted.

Gabriel Tóth of Katedra Komunikácie, a PR and digital agency, thinks the president should continue to try to unite society through communication and not resort to direct political attacks.

“People expect the president to be non-partisan [though all Slovak presidents have come through a political party except Andrej Kiska] and to decently represent the country,” he noted.

A speech in the Ukrainian parliament during the war and Pope Francis’s visit to Slovakia at the invitation of Čaputová are some of the president’s biggest achievements on the international scene.

Decision time

When it comes to trust, Čaputová’s peak is most likely passed, Michal Ovádek, a political scientist from the University of Göteborg, wrote in a February opinion piece, though added that it is not unusual for Slovak presidents to become less trusted over time in office.

He believes further attacks will not affect the president’s popularity, as while opposition voters have already deserted her, coalition voters, such as supporters of Matovič’s party, still favour the president.

Ovádek thinks it would be odd if Čaputová, currently still the second most trusted politician in the country, refused to run in the next presidential election. “The political representation of liberal voters in Slovakia has long been undernourished,” he said.

Čaputová said she would make the decision “at the right time”, considering her family and demand for her continued political service.

She has refuted the idea of leading a political party, however. Before she became president, she was a member of Progressive Slovakia, a non-parliamentary political movement. Today, it would win seats in parliament, according to recent polls. “If she ran, she would lose one advantage – being a newcomer,” Világi pointed out, adding that the Slovak electorate is obsessed with new faces.

Moreover, given the constant attacks on her and the highly polarised nature of Slovak society, in which some people yearn for a dominant leader while others prefer a leader like Čaputová who can make compromises and arguments, her reelection would be far from assured.

Čaputová’s former advisor Marián Leško argued in a recent podcast that Čaputová should run again, but only if she has a real chance of winning. “Otherwise, it would be responsible for her to make way for someone else,” he said.

Kusá, another former advisor, said she would encourage Čaputová to run for reelection. “She wanted to be president for all the people, support dialogue instead of division – and that mission has not been accomplished thus far,” Kusá concluded.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News