Introduction

The ongoing protests against the Iranian regime can be defined not only as a women-led uprising, but also an ethnic minorities-led one. In fact, for the ethnic minorities that comprise almost half of Iran’s population (e.g., Ahwazi Arabs, Kurds, and Balochis), this is a “revolution” for liberty and basic ethnic and human rights of which they have been deprived not only by the Islamic Republic of Iran, but also by the former Persian regimes (e.g., under the Pahlavi dynasty) for almost a century. For this reason, this is as sensitive topic for the Iranian regime as it is for the Persian diaspora itself.

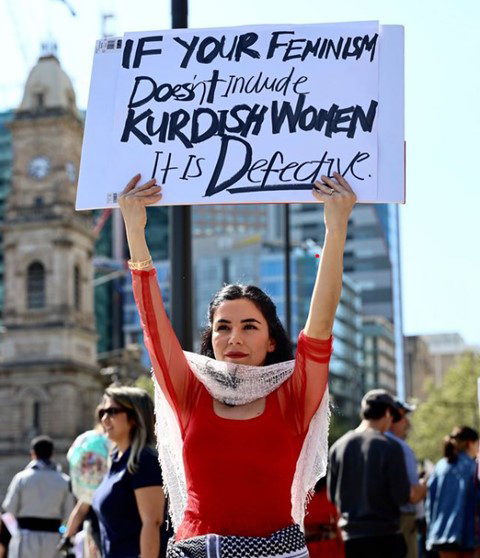

It is worth noting that the protests were sparked all over Iran following the murder of Jina Amini, the 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman who was beaten to death by the Iranian “morality” police. As Kurdish women’s rights defenders in Iran often say: “We are both women and Kurds; so, in the Islamic Republic of Iran, we are doubly accused.” In fact, Jina Amini was arrested, tortured, and murdered not only because she was wearing her hijab too “loosely,” but also because she was Kurdish.[1]

Yet, before the news of Jina Amini’s murder by the Islamic Republic reached the international media, the Persian diaspora strategically erased Jina’s ethnic background and the ethnic character of the Kurdish protests (which started in Eastern Kurdistan in response to the heinous killing), in order to divert the attention of the international community from the dire situation of ethnic minorities in Iran. In fact, both the Persian media in the diaspora and the international media keep on calling her by her Persian name Mahsa, a name she was forced to adopt, as the Islamic Republic does not accept the registration of Kurdish names in official documents.

Often, for example in London and in Aarhurs in Denmark, Persians have not allowed Kurds and Balochis to raise their national flags or display their ethnic symbols at recent anti-regime rallies.[2] Videos shared on social media showed Persians attacking a Kurdish man in Stockholm for wearing Kurdish clothes.[3] In Berlin, Persians harassed Ahwazi Arabs, Kurds, and Balochis for criticizing Mohammed Reza Shah for committing crimes against minorities. A Baloch man was verbally attacked by Persian protestors for holding a placard that read “Iran has committed genocide against Kurdistan and Balochistan.”[4]

Members Of Iran’s Ethnic Minorities All Have A “Jina” In Their Lives

Speaking out against the erasure of Kurds and Kurdistan by the Persian diaspora and the Western media, Kurdish activist Tara Fatehi stated: “You can’t chant ‘Jin, Jiyan, Azadi’ [a Kurdish feminist slogan meaning “Woman, Life, Freedom” used as the rallying cry of the Iranian protests] in the same breath that you erase, re-colonize, and reinforce the oppression of the Kurdish people.”[5]

The story of Jina Amini and the erasure of her Kurdish background by Persians is germane to the experience of all Iran’s ethnic minorities that have disproportionately suffered from state repression, violent “Persianization” and assimilation policies by Persian regimes. Members of ethnic minorities in Iran all have a “Jina” in their lives. Jina represents the daughter of Iran’s oppressed minorities that for decades have undergone systematic discrimination.

Inside and outside Iran, Persians have failed to amplify or even listen to the voices of minorities that form the backbone of the current revolution. The international media’s coverage of the Iranian protests and perspectives as being the sole representatives of Iran, has further marginalized the ethnic and religious minorities and bolstered the Persian-centrism of the Iranian regime. “When was the last time an Iranian Lur or Ahwazi was given a global platform to voice their opinions on Iran’s regime or Western foreign policy towards Iran? How can non-recognized religious minorities such as Bahai’s or Sikh speak globally from within a state that affords them no protections?” scholars Asha Sawahney and Sabrina Azad wrote.[6]

From “Pan-Iranism” To “Aryan Islamism”: “Persianization” And “Centralization” In Iran (1921-Present)

From the late medieval period until the 20th century Iran was a multiethnic empire, with Turkic-speaking and Kurdish dynasties leading the country’s political and military institutions. This changed under Reza Shah, who seized power in a Persian coup d’état in 1921, for he promoted “Persian nationalism” as the state ideology.

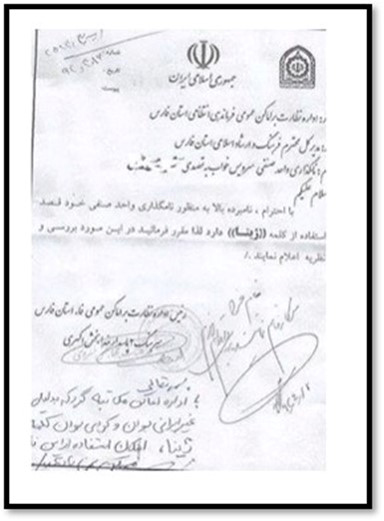

The nationalist framework established by Reza Shah Pahlavi left no room for Iran’s distinct ethnic identities, as a 1925 editorial in a pro-Pahlavi journal argued: “The Iranian state is in danger of crumbling as long as its citizens consider themselves not primarily as Iranians, but as Turks, Arabs, Kurds, Bakhtiyaris, and Turkmens. We must, therefore, eliminate minority languages, regional sentiments, and tribal allegiances, and transform the various in-habitants of present-day Iran into one nation.”[7] To carry out this transformation, the Pahlavis attacked and eliminated the last independent principalities in Khuzestan, Luristan, Balochistan, and Kurdistan. Followed by violent Persianization campaigns, banning local languages and clothes, forced migrations and compulsory resettlement of Kurds, Balochis, and other ethnic groups in the border regions in order to disintegrate their social structures and accelerate cultural-linguistic assimilation.[8]

The Persianization and centralization policies met with strong resistance from the ethnic minorities that engaged in insurgencies against successive Persian governments (1925-1979). Some notable examples were the late 1930s rebellions in Balochistan that were brutally suppressed, and the establishment of the Republic of Kurdistan by Kurds and the Azerbaijan People’s Government by Azeri Turks in 1945. Both were violently dissolved a year later and the Kurdish leaders were publicly hanged in Mahabad square. The Iranian army, backed by the U.S. and the U.K., occupied the border regions in December 1946, leaving a trail of death and destruction.[9]

Despite officially adopting Islam as the state ideology in 1979, the Islamic Republic retained the Shah’s Persianization and centralization policies. In fact, Islamization has been, in a way, the reverse side of Persianization. The ideological use of religion by Ayatollah Khomeini initiated a fusion of the Shi’ism and “Persianism” as the two main elements of nationalism. Unlike the Persian-secular ethno-nationalism of the Shah’s regime, the Persian-Shi’ite ethno-nationalism formed the basis of the Islamic regime’s domestic policies and colonization strategies. Thus, in an implicitly imperial colonial orientation, the 1979 Islamic regime did not recognize the rights of self-determination of non-Persian ethno-nations, especially the Kurds who demanded them.[10]

The cultural term “Aryan” or “Iran” (“noble people”) was historically the self-designation of many ethnic groups in Southwest Asia, including Indians, Persians, Kurds, and Pashtuns. The modern usage of the term by the Iranian regimes, however, has been limited to “Persians.” Iran does not appreciate the so-called “Iranian languages” such as Gilaki, Kurdish, Balochi, etc. Among 75 languages spoken in the country, Iran has only recognized Persian, the rest have faced linguicide and many of them are going extinct.[11]

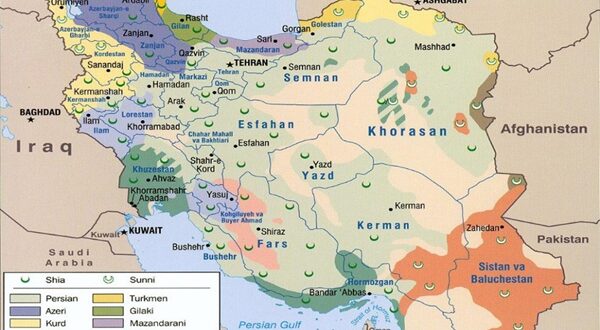

Iran’s Ethnic And Religious Minorities

Persians comprise almost half of Iran’s 84,000,000 people; the non-Persian ethnic minorities form the overwhelming majorities in the peripheral regions of Iran, in contrast to Iran’s Persian-dominated center. The ethnic minorities share stronger ties with co-ethnics in bordering states than with Persians inside Iran. In fact, they share a widespread sense of discrimination and deprivation toward the Persian-centric regime.

Concerning religions allowed in the country, Iran’s constitution names the Twelver Ja’fari School of Shi’a Islam as the state religion. It recognizes Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian Iranians, that comprise less than one percent of the country’s population, as the only recognized religious minorities, although they have historically been persecuted, imprisoned, executed, and forcibly exiled. The Sunnis, Yaresan (Ahl-e Haq), and the Baha’is have faced the most brutal persecution over the last four decades because Iran has excluded them from the minimum protections and recognitions granted by Iran’s Islamic Constitution.

The Islamic Republic has “disproportionately targeted minority groups, including Kurds, Ahwazis, Azeris, and Baluchis, for arbitrary arrest, prolonged detention, disappearances, and physical abuse,” according to the State Department 2019 Human Rights Report. “These ethnic minority groups reported political and socioeconomic discrimination, particularly in their access to economic aid, business licenses, university admissions, job opportunities, permission to publish books, and housing and land rights.”[12]

In his July 2019 report, the UN Special Rapporteur noted that Kurdish political prisoners charged with national security offences represented almost half of all political prisoners in Iran.[13] Abbas Vali, professor of social and political theory at the Department of Sociology at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, said: “Iranian Kurdistan is treated as a security zone, the logic of military rule has never disappeared,” he continued “when they smell trouble, they first turn to the Kurds.”[14] A report by Iran Human Rights (IHR) shows that over 55 percent of political prisoners executed between 2010 and 2018 were Kurds, while 25 percent were Baluchis and 13 percent Arabs.[15]

Azeri Turks, who are predominantly Shiite, are the second-largest ethnic group in Iran and account for 15-20 percent of the population. They form majority in Azerbaijan in Northwestern Iran. Their neighbors Gilakis and Mazendaranis together make up around nine percent of the population, forming a clear majority in provinces bordering the Caspian Sea, which contain the world’s tenth-largest gas reserves.[16] Kurds are the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East, and the third largest ethnic group in Iran, comprising around 10 percent of the country’s population. Kurds live in Northwestern Iran, which Kurds call Rojhelati Kurdistan (“East Kurdistan”). Iran, Turkey, and the neighboring countries have long perceived the Kurds as a threat due to their numbers, geographic distribution, and resistance to the central authorities.

Khuzestan province – called Iran’s “Achilles’ heal” – in western Iran is home to the largest Arab community, known as Ahwazi or Khuzestani Arabs that account for 2-4 percent of Iran’s population.[17] The province contains almost 80 percent of Iran’s oil reserves and the bulk of its natural gas production. The province is also one of the largest producers of grain, corn, rice, sugar beet and sugar cane. It is also home to the country’s biggest steel exporter.[18] Their neighbors are the Lurs, who comprise around six percent of Iran’s population.

Sistan and Baluchistan province in southeastern Iran is home to 1,500,000 to 2,000,000 Baluchis, who are predominantly Sunnis and make up about 2 percent of the national population. Balochistan is one of Iran’s most strategic frontiers. It shares a nearly 200-mile border with Afghanistan and a nearly 575-mile border with Pakistan. Chabahar, in Sistan and Baluchistan province, is Iran’s only oceanic port, on its coast on the Gulf of Oman. The province already has some 370 active mines, but millions of tons of mineral reserves, including gold, have yet to be extracted.[19]

Center Vs Periphery

Although half of Iran’s human capital as well as most of Iran’s natural resources are concentrated in the frontier provinces, the Persian regions have enjoyed far better economic development, better job opportunities and government services vis-á-vis the border provinces, which are characterized by a lack of economic development and high unemployment rates.

A 2019 UN report indicates that in Sistan and Balochistan province the vast majority of the Balochis lives below the national poverty line.[20] High unemployment among Kurds has forced many to take jobs as “kolbars,” or smugglers and couriers carrying goods between Iraq and Iran. The job is dangerous due to harsh weather, mountainous terrain, land mines, and Iranian border patrols. In 2019, 50 “kolbars” were reportedly killed and 144 injured by border guards.[21] On January 6, 2021, Mohsen Haidari, representative of Khamanei in Khuzestan, confessed that there is an unacceptable level of discrimination against Arabs in Khuzestan: “Though Arabs constitute the majority of the population in the province [Khuzestan], they hold less than five percent of the local management positions. In job interviews, when the interviewers check the identity card of the Arab applicant and realize that the person is Arab they reject them. Young Arabs started to change their names to hide their Arab identity in order to get hired.”[22]

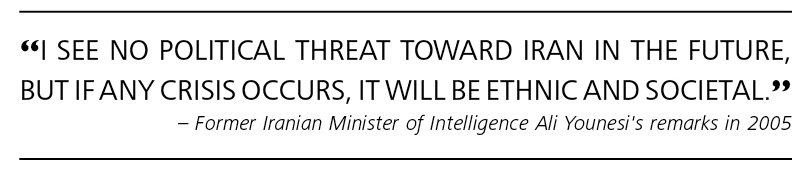

Iranian political scientist Nader Entessar pointed out the existence of center-periphery inequality in Iran and the subsequent sociopolitical and economic inequalities experienced by the minorities have given rise to a condition akin to internal colonialism and to reactive movements organized by the marginalized groups or the periphery in reaction to their exclusion from the state machinery by the central regime.[23] The intersectional discrimination against minorities has strengthened ethno-nationalism in the peripheral regions which the Iranian authorities perceive as the most serious threat to Iran’s territorial integrity.

Ali Younesi, then Iranian Minister of Intelligence, remarked in 2005, “I see no political threat toward Iran in the future, but if any crisis occurs, it will be ethnic and societal.” A 2004 Iran’s Interior Ministry study concluded that ethnic identity awareness has largely increased among Iran’s major ethnic groups. For this reason, since the beginning of the 2022 anti-regime protests, predominantly happening in the border regions – as mentioned by Suzan Quitaz, a Kurdish-Swedish researcher and journalist at Saudi-owned media outlet Majalla – “Iran’s ethnic minorities are disproportionally suffering,” as “the Iranian security forces’ response to the protesters differs by region.”[24]

Quitaz also wrote: “Compared to the central parts of Iran, peripheral regions such as Khuzestan and Kurdistan (populated by Arabs and Kurds, respectively) had higher rates of death and arrest of protesters.” She then noted that while the protests sweep Iran’s big Persian cities, “the IRGC is committing war crimes against Iran’s marginalized communities, mainly by using horrific brutality against the Baluchi and Kurds.”[25]

Islamic Republic’s Military Expansionism And Colonialism

Since its foundation in 1979, the Islamic Regime has pursued its hawkish, expansionist ideology of “exporting the Islamic Revolution” into the Shia-majority countries through war and political violence.[26] Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), the main mechanism for foreign intervention, has enabled Iran to take control of Gaza, Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, and Syria through its proxies, which Iran calls the “axis of resistance,” a network of internationally designated terrorist organizations[27] with an almost 40-year track record of terrorism.

In fact, Ayatollah Khamenei is no longer the supreme leader of Iran alone. He is now also the unofficial, but de facto, supreme leader of Iran’s colonies such as Iraq, Yemen, Gaza, Syria, and Lebanon. This fact was explicitly stated by General Yahya “Rahim” Safavi, Ayatollah Khamenei’s military advisor and former commander of the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), who claimed: “Lebanon’s border with Israel is Iran’s new defensive line,” and added that “The West is worried that Iran’s influence is spreading from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean.”[28]

More recently, when the influential Iraqi Shia leader Muqtada Al-Sadr, widely considered the leader of the anti-Iranian Shia front in Iraq, tried to reduce Iran’s hegemony over Iraq, he was forced to pay allegiance to Khamenei after a Fatwa was issued by Al-Haeri, his spiritual leader based in the Iranian city of Qom, calling on Al-Sadr and his followers to support Ayatollah Khamanei.[29] Thus, handing over Iraq’s sovereignty to Iran.

Iran has recently expanded its military presence into Eastern Europe as well where the regime, in violation of the U.N. ban, has assisted Russia in the war against Ukraine through supplying it with drones and missiles along with IRGC technicians to work on drones. The White House said that the U.S. has evidence that Iranian troops are “directly engaged on the ground” in Crimea supporting Russian drone attacks on Ukraine’s infrastructure and civilian population.[30]

The Islamic Republic of Iran has undermined the sovereignty of several states and involved in the suppression of Middle Eastern democratic movements. Iran, like Turkey, prevents religious and ethnic minorities from gaining any sort of regional standing or independence that could be perceived as a threat to Iran’s regional interests and national security. For instance, in 2017, IRGC’s Quds forces commander Qassem Soleimani led the Shia militias in the invasion of Kirkuk, murdering 600 Kurdish civilians, after the Kurds held a referendum for independence in the city. The Chief of Staff of Iran’s Supreme Leader later announced: “Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and the Quds commander Qassem Soleimani have spoiled an American-Israel plot to create a second Israel in the Kurdistan Region.”[31]

Conclusion – Toward A Balkanized Iran: Why The Ethno-States Matter

Support for the balkanization of Iran into several independent ethno-states is desirable for multiple parties, first and foremost, for the oppressed minorities. The formation of new ethno-states in Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Khuzistan, Baluchistan and Caspian provinces would engulf Iran from all sides and limit its access to the coastline and the main ports in the Gulf and Caspian sea, and the abundant natural resources in the border regions. This will effectively cripple Iran as a powerful and expansionist state, since it would lose half of its human capital and most of its natural resources, which are vital for its military strength and expansionism in Southwest Asia.

A resourceless Iran poses no threats to the neighboring and regional states as well as to the international community’s interests. An Iran without Balochistan, Kurdistan, Azerbaijan, and Khuzestan will be an isolated, immobile land. Furthermore, the many Iranian-backed terrorist groups, responsible for most of the mayhem and destruction in the Middle East, would no longer operate.

It is worth noting that a regime change in Iran might end Iran’s imperialism and its authoritarian theocratic rule, but it may not end the persecution of its minorities. The will of the minorities, that united together comprise almost half of Iran’s population, should be respected and their right to statehood and liberty recognized. Dividing Iran along ethnic lines serves local, regional, and international interests. Any future plan or foreign intervention should be toward that end.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News