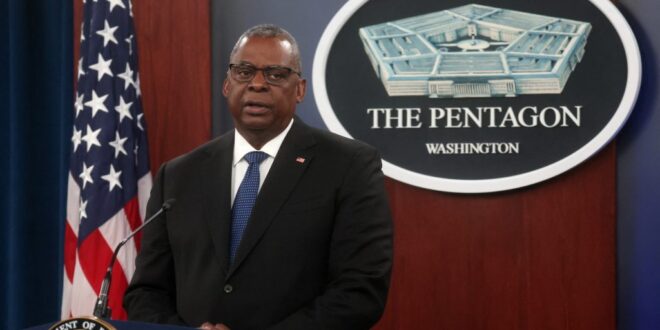

On Thursday, the Pentagon released its long-awaited 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS), along with the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) and Missile Defense Review (MDR). Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin wrote in the strategy’s introduction that it will shape the department’s priorities during the coming “decisive decade—from helping to protect the American people, to promoting global security, to seizing new strategic opportunities, and to realizing and defending our democratic values.” Does the strategy succeed? Does it adequately address Russian aggression in Ukraine and the multifaceted challenges from China? What’s missing?

We asked experts from across the Atlantic Council—many of whom worked to develop these documents during their time in government—to break down the highs and lows of the strategies and pull out the key things you need to know.

- The NDS undersells the threat from Russia to the US

The 2022 NDS categorizes the threat from the Russian government as “acute,” encompassing the immediacy of the threat and the targeted nature of the current operational environment. This distinction from the “pacing” and “strategic competition” threat posed by the People’s Republic of China represents a shift from the Defense Department’s threat priorities from the 2018 NDS, putting Russia as the clear number-two priority. Though delays to the NDS release are reportedly connected with the Russian invasion in Ukraine, the Department in fact chose to deemphasize the detrimental impact Russian actions have on US national security.

While the NDS gives the Russian threat credibility and addresses the need for prompt action, assistance, support, and strong cooperation with partners and allies, it describes the Russian threat as localized and predominantly asymmetric in nature. This threat description poses a precarious balance for the Department. Though Russia has recently demonstrated embarrassing performances on the battlefield, the second-tier ranking of the Russian threat in the NDS must not deter vigilance against the global chaos Russia sows. Russia does not use the Western playbook of rules or principles to dictate its direction, and the United States would be wise not to apply Western thought processes and decisionmaking to an authoritarian and fearful government that has thrown caution and pragmatism to the wind.

You only need to look at some of the Russian malign actions and tactics since February—subversive energy policy, economic warfare, food-supply threats, misinformation, nuclear threats, and sabotage. Many of these actions have worldwide reach with no signs of slowing. Meanwhile, Russia continues to back itself into a corner of its own making, growing its reliance on its pernicious partners—which the NDS also identifies as threats—China, North Korea, and Iran to support its malicious foreign policy goals. And though this isolation is of Russia’s own making, the United States should not interpret its failures to mean that Russia cannot bring tumult and instability in the near, medium, and long term. The NDS correctly highlights the threats Russia poses, but decisionmakers must not fall into the trap of assuming current Russian embarrassments as foregone conclusions. The United States must address all of the subversive and dangerous ways Russia can pose a threat to its security.

—Catherine Sendak is a nonresident senior fellow in the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security’s Transatlantic Security Initiative and former principal director for Russia, Ukraine, and Eurasia in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy.

- Tough talk on China will provoke a response from Beijing

The biggest takeaway for me is the strategy’s new focus on homeland defense challenges posed by Russia and China, rather than military contingencies in the Indo-Pacific or Europe, an emphasis that touches domestic political vulnerabilities in addition to those of the military and core infrastructure. Combined with the emphasis on “Campaigning,” it sends a strong message that the world is actively contested now, and that the Department of Defense (DOD) and all of the US government is not just preparing for potential kinetic conflict, but engaged already in active contestation focused on China, and secondarily Russia.

The big question now is how China will read this and whether it will deter or spur them to accelerate their own, already massive military and technological transformation. The NDS’s focus on “Campaigning” will signal that DOD and other US departments are already conducting operations to disadvantage China—tantamount to a new Cold War. The era of DOD claiming that its activities—freedom of navigation operations, reconnaissance flights, multilateral exercises—are merely “things we have always done” is over. This will incentivize Chinese responses, especially with US allies and partners in the region, including pointed exercises by the People’s Liberation Army. Moreover, the NDS’s emphasis on integrated support and operations with allies and partners will underscore the threat to China of US designation of Taiwan as a “key non-NATO ally,” potentially breaking existing US policy barriers to a virtual defense guarantee.

—John K. Culver is a nonresident senior fellow at the Global China Hub and former US national intelligence officer for East Asia.

- The “integrated deterrence” approach needs clearer lines between DOD and DHS

How will DOD work with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to protect the United States from non-military attack under the NDS’s “integrated deterrence” approach? Non-military security is an increasingly important issue that the NDS addresses, but at key points the NDS paints only a few dotted lines in the road without clearly stating where the lanes will be. When the country is engaged in military conflict, DOD is the “supported” department, and other departments and agencies are “supporting” DOD and the defense industrial base in fighting and winning the United States’ wars. But the NDS is less precise about when, and to what extent, DOD will be the “supporting” command to departments like DHS in defending civilian infrastructure such as the financial sector, pipelines, water systems, and electrical grids. Make no mistake: DOD needs these civilian sectors functioning to meet the military threats that the NDS addresses.

Security challenges in the coming years will increasingly be campaigns waged against the American people using non-military means. China, Russia, and Iran have all adopted hybrid warfare strategies against the United States and its allies. As part of Russia’s kinetic war against Ukraine, Russia is simultaneously waging information warfare to divide and weaken the American people. Russia’s campaign against Europe over natural gas supplies this winter is already underway. In 2013, then General James Mattis testified that if Congress did not fund the State Department, “then I need to buy more ammunition.” A similar warning needs to be issued today about funding US civilian efforts in cybersecurity and other missions—for which DHS, rather than DOD, will need to be the supported command.

—Thomas Warrick is a senior fellow at the Scowcroft Center’s Forward Defense practice and director of the Atlantic Council’s Future of DHS Project. He is a former DHS deputy assistant secretary for counterterrorism policy.

- Inside a revealing battle of the buzzwords

The 2022 NDS is about relationships—relationships between the United States and its top two adversaries, complex relationships between compounding threats across all domains, and relationships between the United States and its allies and partners. These relationships are complicated. Managing escalation is key in the new strategy, as the threat of unintended escalation is greater now as the United States faces increased aggression by Russia and China and grapples with the unknown ways that new technologies could complicate pathways for escalation, especially in the space and cyber domains where pre-established norms are lacking. These more complicated relationships have led DOD to adopt “integrated deterrence.” Integrated deterrence is extremely complicated, but it at least is better defined than “deterrence” in the 2018 NDS, which did not articulate enough the specific activities in specific domains that the strategy was aiming to deter. From this logic of integrating deterrence against increasingly complicated threats, you can better understand why the NDS has downgraded Russia from a great-power competitor to an “acute threat,” even if you don’t agree with it.

These security strategies are a battle of buzzwords, and I would say the buzzwords in the 2022 NDS have surprised me. The biggest surprise is the return of A2/AD: anti-access/area-denial. Russia and China seek to create A2/AD environments that undermine US conventional and nuclear force advantages and collective responses with allies, and a key way to overcome this, according to the NDS, is by developing concepts and capabilities that can “penetrate adversaries at range.” But missing from the NDS is the much-buzzed-about concept of joint all domain command and control (JADC2) or multi-domain operations (MDO), which seems strange on the same day that a new JADC2 office is opened in the Pentagon, which could also help overcome adversary A2/AD advantages.

Secondly, this NDS also does away with many of the key phrases from the 2018 strategy, such as the “global operating model” and “dynamic force employment” (which my colleagues took a stab at clarifying last year), but then seems to encompass them in an overall new buzzword: campaigning. But it lacks specifics in how the United States will enable deterrence by denial and overcome A2/AD challenges without an increased and sustained presence in Europe, which is never directly addressed. Beyond concepts, another key buzzword in the NDS is “resilience,” which is mentioned in some form over thirty times and in more nuanced ways that include resilience against climate change and resilience in the face of degraded operating environments caused by adversary A2/AD threats. Overall, there are some welcome changes and a lot more work to further define and implement them.

—Leah Scheunemann is the deputy director of the Scowcroft Center’s Transatlantic Security Initiative and former special assistant to the US undersecretary of defense for policy, overseeing matters related to international security.

- The focus on integrated deterrence, and the gray zone’s role in it, is long overdue

The NDS offered a much-needed discussion about integrated deterrence, and while the national-security community has its work cut out in implementation, that discussion over how to effectively use all existing and new “tools at the Department’s disposal” to maintain the strategic advantage was also a decade overdue.

In the NDS, Austin further expanded on the elements of integrated deterrence from US President Joe Biden’s National Security Strategy. It was heartening to see that the gray zone was explicitly noted as part of the security environment on the topic of strategic competitors and adversaries and that it was also indirectly highlighted from an offensive or deterrent perspective through imposing costs, leveraging the information domain, and managing escalation. In the context of campaigning to sustain military advantages, the NDS explicitly called out “[addressing] gray zone challenges” as an objective.

To truly and effectively integrate deterrence, the United States must avoid tunnel vision in developing conventional general-purpose and strategic deterrent forces. Such forces are a competitive advantage, and must continue to remain so, particularly in the eyes of competitors and adversaries. A credible conventional and strategic deterrent underwrites all other US and allied elements of statecraft. But integrated deterrence also means placing as much emphasis on the things that do not necessarily go “boom,” making good use of the maneuver room enabled by the deterrents. Defending against gray-zone operations activities and actions, while effectively using the country’s own, will be key to this. Allied perceptions of US reliability as a partner will also continue to be critical to integrated deterrence and must reinforce that the United States can always be relied upon to defend and support its friends, regardless of domestic political winds.

—Arun Iyer is a nonresident senior fellow at the Scowcroft Center and leads its project “Adding Color to the Gray Zone.” He served in a variety of operational and operational leadership assignments in the US Department of Defense.

- The NDS’s priorities are correct, but it may have taken on too much

This strategy should be heralded for its clear articulation of threats: It rightly places China at the top in the hierarchy of strategic challenges facing the United States, as the “pacing” threat. This is a departure from the 2018 NDS, which categorized Russia and China somewhat similarly. Russia is an “acute” challenge—an immediate and fierce threat—but not an all-domain challenge in the way China is. The strategy emphasizes the need to build “enduring advantages” to modernize and build up the Joint Force, and it integrates strategic deterrence concepts with conventional deterrence. Highlighting the compounding challenges to escalation dynamics from emerging technology and in domains like cyber and space is a worthy focus area.

That said, the NDS may have taken on too much—and it falls down in a few areas. First, the three strategic ways outlined in the NDS are still not clearly defined and could lead to confusion. “Integrated deterrence” is defined around altering adversary perceptions of risk, but if the types of malign behavior that the United States is trying to deter are not broadly understood across the Defense Department, this will be hard to achieve. Second, collaboration with US allies and partners is rightly emphasized throughout as a “strategic advantage,” yet integration with allies will require enhanced operational and strategic planning that is hindered by current barriers to information sharing and technological cooperation. Third, to compete with China’s advances in artificial intelligence, undersea capabilities, quantum computing, and directed energy, the United States needs to absorb technological innovation more rapidly from the leading edge of the private sector than it does today. The NDS talks about working across the defense industrial base to sharpen the Joint Force’s “technological edge,” but there’s scant detail on how cultural and process roadblocks will be adapted to enable better engagement with the private sector and adoption at speed.

The NDS provides a solid vision, but it will take substantial resources to implement—a difficult task given the multitude of investments outlined in the strategy and the fiscal constraints on the Pentagon. Responding to immediate concerns from Russia in Europe along with long-term competition with China will require the administration to make trade-offs. The ultimate success of this strategy relies on how well those trade-offs are managed in its implementation.

—Clementine G. Starling is the deputy director of the Scowcroft Center’s Forward Defense practice.

- While the nuclear landscape has changed, the NPR continues the status quo

With its new NPR, the Biden administration takes into account today’s strategic realities and follows a well-carved path prioritizing nuclear deterrence. The nuclear landscape has changed with the United States now confronting not one but two nuclear powers—Russia and China—both of whom are expanding and modernizing their arsenals. These nuclear developments are happening alongside a return to more traditional great-power politics, on display with extreme clarity in the war in Ukraine. For these reasons, the NPR emphasizes the United States’ leadership in the nuclear environment, including recommitting to a “safe, secure, and effective nuclear deterrent;” placing pride of place in alliance partnerships and regional security architectures; modernizing the nuclear infrastructure and related systems; and rededicating US efforts to “arms control, non-proliferation and risk reduction.”

Despite earlier indications on the campaign trail and elsewhere that the Biden administration (like the Obama administration) would attempt a significant shift in US nuclear weapons policy— including adopting No First Use and Sole Purpose policies—the possibility has now been shelved. Both policies remain hotly contested in the United States and in ally countries under the nuclear umbrella, and it is unsurprising that the administration views the present security environment as not conducive to a dramatic reorientation.

While the NPR does remove “hedging against an uncertain future” as a stated role for nuclear weapons from the United States’ description of its role for nuclear weapons, and cancels the sea-launched cruise missile program, it also retains the W76-2 low-yield submarine-launched warhead introduced in the Trump administration. Taken holistically, critics of nuclear deterrence and advocates of global zero will likely be disheartened by an NPR that reads largely as a status quo continuation of long-standing nuclear policy attuned to the current strategic challenges facing the United States.

—Rachel Whitlark is a nonresident senior fellow in the Scowcroft Center’s Forward Defense practice and an associate professor at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

- A subtle policy shift on nuclear weapons offers a measured response to Putin

Despite Biden’s campaign trail pledges to reduce the role of nuclear weapons, this NPR responds to the reality of the current security environment. With many nods to the 2018 NPR, three things will likely stand out to most readers—the administration’s shift to a “fundamental purpose” declaratory policy, the removal of “hedging against an uncertain future” as a role for nuclear weapons, and the elimination of the Nuclear Sea-Launched Cruise Missile (SLCM-N), a system initially identified in the 2018 NPR as a “needed non-strategic regional presence” and “an assured response capability” meant to deter and respond to limited nuclear attack.

Though seemingly inconsequential, this shift to a fundamental purpose statement and the elimination of the SLCM-N suggests a larger change in the administration’s thinking about the role of nuclear weapons—namely, that some in the Biden administration believe that escalation dynamics surrounding nuclear weapons cannot be controlled. In many ways, the change in this strategy—which was delayed due to Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine—shows a measured response to months of nuclear-saber rattling from Russian President Vladimir Putin. It is a stark reminder that a nuclear strike would, in the words of National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, have “catastrophic consequences,” and though the NDS as a whole is shaped around China as a future adversary, this NPR was clearly crafted with Russia’s limited nuclear threats in mind.

The core tension in the document lies in its desire to avoid the use of nuclear weapons except in extreme circumstances while also maintaining a credible deterrent against adversarial nuclear use. While the most obvious way to deter an adversary’s nuclear use is to be prepared to use nuclear weapons oneself, this NPR’s elimination of the SLCM-N shows that this administration may be intending to rely more heavily on conventional means to deter and respond to limited nuclear attack, given that the SLCM-N was conceived explicitly as an answer to non-strategic nuclear systems—otherwise known as “tactical” nuclear weapons. The emphasis on the synchronization of nuclear and non-nuclear planning and operations further indicates that the administration may believe that conventional rather than nuclear weapons might provide an adequate response to a limited nuclear strike, and while that might be true with the right set of precision-guided conventional weapons, there is some tension between such a response and the implied taboo of nuclear use. Even as it struggles with this tension, though, the 2022 NPR nevertheless gives a mature treatment of the risks of this coming, tripolar nuclear environment in which the United States will for the first time face two nuclear powers at once as strategic competitors.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News