On 5 June, 2014, hundreds of ISIS militants launched a lightning assault on Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city. As a result of the mass surrender and desertion of the Iraqi forces, ISIS took full control of the city on 10 June, just 5 days later. The group looted banks, freed prisoners, and captured significant amounts of US-supplied military equipment in the process.

But how did Mosul fall so easily? Why did four divisions of the Iraqi army, some 50,000 soldiers, withdraw without a fight in the face of just hundreds of ISIS militants attacking the city?

The conventional view argues that the Iraqi army collapsed due to corruption and the sectarian policies under former Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki – a Shia, whose discriminatory policies led Mosul’s primarily Sunni residents to view the Iraqi army as an occupying force, and to welcome ISIS into the city as liberators.

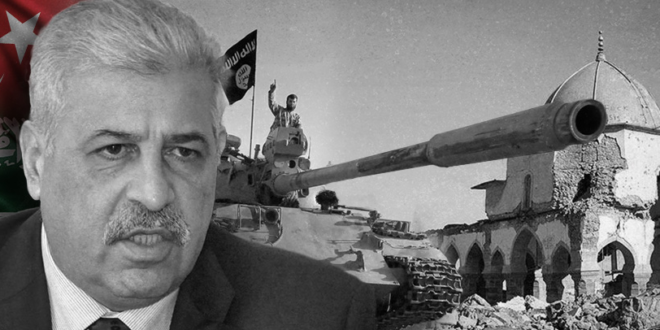

How Mosul fell to ISIS

However, a closer review of events in Mosul shows that the fall of the city was not due to popular support from the city’s residents, nor due to popular anger against Maliki’s sectarianism. Instead, the fall of Mosul was facilitated by then-Nineveh Governor Atheel al-Nujaifi, who was both collaborating with ISIS and acting as a Turkish proxy.

This effort was assisted by the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), all of which wished to see Mosul fall to ISIS as well.

This view is supported by testimony from members of the Nineveh Provincial Council given to an Iraqi parliamentary committee tasked with investigating how the city fell. The parliamentary committee concluded that the “plot to allow Mosul to fall into the hands of Daesh [ISIS] was not only military but also political and administrative, suggesting that figures in the local government were involved in the conspiracy.”

Iraqi parliament member Abd al-Rahman al-Louizi, who was also a member of the parliamentary committee, cites the role of governor Nujaifi specifically, and provides details of the preparations made by Nujaifi to allow the city to fall.

Writing in al-Akhbar, Louizi explained that Baathist militants from the Naqshbandi Army (a Sunni militia of former Baathist officers who fought alongside ISIS) had attempted to take Mosul on 25 April, 2013, in the wake of Maliki’s order for the army to clear a protest camp in Hawija, near Kirkuk, where various Sunni groups were participating in a sit in to protest Maliki’s government.

Baathist militants briefly took control of several neighborhoods in northwestern Mosul, but these were retaken by the security forces the following day. Some 300 people died in the violence.

As a result, the Baathists realized they could not expel the security forces on their own and decided to use ISIS as a “strike force” to launch a future attack on the city. The Baathists prepared for this by forming “military councils of tribal revolutionaries,” that could take control of the city in the wake of such an attack.

Louizi further cites a secret cable from Iraqi intelligence which referred to a 26 January, 2014 meeting attended by Baathists at the home of a Mosul sheikh, whereby they discussed the formation of the military committees and a future attack on the city. Attendants of the meeting agreed that, in the event of an assault on Mosul, governor Nujaifi and the local police would not intervene to stop it.

They also discussed assigning an ISIS commander to coordinate the offensive, and the need to approach Kurdish officials in order to request their neutrality.

Early indications of Nujaifi’s collaboration with the militants that would form ISIS stretch back years. In a 2009 letter published by West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center, an Islamic State of Iraq (ISI, precursor to ISIS) member in Mosul discussed the “old friendly relationship between him [Nujaifi] and our brothers, Abu Ahmed and Abu Leith.”

Louizi cites testimony given to the parliamentary committee from members of the Nineveh Provincial Council, in which they state that Nujaifi openly discussed the coming attack and fall of Mosul during another meeting, in March 2014, and that Nujaifi described his plan to “protect the city” using the local police, the tribal military committees, and even the Kurdish Peshmerga if necessary.

Betrayal from the top brass

When the ISIS assault on Mosul began on 5 June, 2014, the militants initially faced resistance from units of the National Police. However, on 9 June, the four brigades of the Iraqi army tasked with defending the city withdrew without a fight, allowing ISIS to take full control of the city the following day, 10 June.

According to an Iraqi soldier from Baghdad who fought in Mosul, his commanding officers “betrayed us, they just left and didn’t give any orders” and returned to Baghdad by helicopter, forcing the low-rank soldiers to make their way to Erbil in search of safety.

This raises the question of who issued the orders for the commanders to withdraw. The parliamentary investigation concluded that explicit orders were given to army commanders to withdraw but did not state who was responsible for issuing them.

Shedding light on this, Reuters reported that Iraqi Generals Ali Ghaidan and Aboud Qanbar, who had been tasked by Maliki with commanding the army in Mosul, fled the city on the night of 9 June, shortly after a meeting at a military base with Nineveh Governor Nujaifi and his advisor, Khaled al-Obeidi.

According to Lieutenant General Mahdi Gharawi, the operational commander of the National Police in Nineveh province, Nujaifi and Obeidi left the base after the meeting at 8:25 pm. Then Qanbar and Ghaidan informed him (Gharawi) shortly before 9:30 pm that they were withdrawing across the river to east Mosul, while giving him no reason for their withdrawal.

Gharawi explained that this was “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” which was followed by mass desertions of conscripts, the flight of the army commanders, and the full ISIS occupation of the city.

The timing of this meeting between Nujaifi and the two generals, and their immediate flight thereafter, suggests Nujaifi may have played a role in issuing the order for the army to withdraw.

According to Iraqi Corporal Muammer Naser, Qanbar and Ghaidan were sympathetic to Baathist ideology and therefore “essentially passed control of the city” to the Naqshbandi Army. Ghraidan and Qanbar were the first to flee the city, Naser maintained.

Nujaifi and the ISIS ‘liberators’

Governor Nujaifi’s actions after ISIS militants entered Mosul further point to his role in facilitating the fall of the city. Shockingly, Nujaifi publicly welcomed the ISIS militants, portraying them as liberators.

Omar Mohammed, Mosul native and author of the blog Mosul Eye, explains that on 8 June, as rumors were spreading of ISIS militants being present in the western part of the city, Nujaifi appeared in the middle of the night, next to the governate building, holding an AK-47:

“He addressed the people and was saying that there is no reason to worry, everything is under control and those who came to Mosul came to liberate us from the oppression of the central government of Baghdad, the sectarian government, those are our brothers, and they are here to free us from that injustice.”

Mohammed explains further that when the video of Nujaifi’s speech spread on social media and Arab satellite channels, this “stopped all the movement of the people, thousands of people, my family included. We were escaping the city. Everyone was escaping the city. A day later, Nujaifi leaves Mosul. In doing so, he condemned Mosul to a fate he wouldn’t face himself.”

Interviews carried out by Mohammed with residents reveal how Nujaifi’s message, encouraged them to stay in Mosul rather than take the opportunity to flee. They were therefore forced to suffer under years of ISIS’ extreme fundamentalist religious rule.

Mohammed notes the confusion was compounded further when the ISIS militants controlling the streets in the first days did not reveal their identities, instead telling residents “We are rebels,” or “don’t worry, we are locals like you.”

Even residents who initially assumed the city had fallen to ISIS, were reassured by militants who claimed to be “revolutionaries” whose aim was to force Maliki to resign. This also encouraged residents to stay in their homes rather than flee the city.

Nujaifi again expressed explicit support for the fall of Mosul in a Facebook post on 26 July, 2014, six weeks after the city’s fall, describing the ISIS militants occupying the city as “battalions” of the “sons” of Mosul. Nujaifi explained that:

“Whoever thinks that the militias or Maliki’s army still has the ability to return to Mosul or fight in the governorates that are rising up is delusional, since that history ended on June 10th [the day the city fell to ISIS]. An army that has collapsed in such awful defeat, and lost its positions and weapons, cannot return to fight again, and the militias cannot fight in a land that does not accept its presence. In the face of this failure in the Iraqi security system and its sectarian formations, the people of Mosul have nothing to rely on but themselves and the battalions of their sons that will liberate Mosul and remain defending it against any attack. These battalions are the ones that will shape the new future of Nineveh.”

ISIS had publicly issued its “Wathiqat al-Madinah” or city charter detailing the new rules the extremist group was imposing on Mosuli society two weeks earlier, on 13 June. This was reported widely in the Iraqi and Arabic press at the time. This means there was absolutely no question that it was primarily ISIS, and not Baathists from the Naqshbandi army, who had invaded and occupied the city by the time Nujaifi wrote his Facebook post on 26 July.

Turkey’s hand

Nujaifi was likely not collaborating with ISIS of his own volition, but with the backing of his main political sponsor, Turkey, which had worked to expand its influence in Mosul in the wake of the illegal 2003 US invasion of Iraq. According to journalist Fehim Tastekin, this included sponsoring prominent Sunni Arab figures in the region, including Nujaifi.

Al-Mada newspaper reported that the head of the parliamentary committee investigating the fall of Mosul stressed that the city’s Turkish Consul Ozturk Yilmaz was the “actual governor” of Nineveh. This claim was based on the testimony of the province’s intelligence service head and on the consul’s various meetings with suspicious figures before the city fell.

Unfortunately, diplomatic considerations prevented the parliamentary committee from summoning the Turkish consul for questioning during the investigation.

This suggests that Turkish Consul Yilmaz worked with Nujaifi to facilitate the fall of the city. Nujaifi would not have done so if not directed by his Turkish sponsors, who also collaborated closely with ISIS.

Turkey’s support for al-Qaeda groups in Syria was well established before the ISIS assault on Mosul. In October 2013, the Wall Street Journal had reported that Turkish intelligence acted like a “traffic cop” to facilitated the transfer of weapons across Turkey’s 565-mile border with Syria in support of jihadist groups.

Al-Monitor reported that this had earned Turkey the label of “the country nurturing al-Qaeda linked groups,” citing many incidents reported by Turkish parliamentarian Mehmet Ali Edipoglu on Turkish intelligence support in moving weapons and fighters across the border to radical Islamist groups.

Additionally, Turkish intelligence officers were meeting directly with ISIS commanders in Turkey. Ahmet Yayala, a former Turkish counterterrorism police officer, said in an interview that Turkish intelligence (MIT) has “consistently helped ISIS, directly or indirectly,” and that in 2014 “we saw the terrorists meeting with our own service. It was extremely upsetting.”

In October 2014, Vice President Joe Biden acknowledged the role of Washington’s Persian Gulf and Turkish allies in supporting ISIS during a speech at Harvard University.

Neo-Ottoman dreams

But why would Turkey want ISIS to conquer Mosul? Turkish journalist Fehim Tastekin explained that for many in Turkey, “Mosul remains a ‘lost homeland’ that slipped through Turkish fingers as the Ottoman Empire collapsed,” and that according to this thinking, “the entire historical Mosul Vilayet should become autonomous and Turkey should lie in wait for an opportunity to annex the region.”

NBC News similarly noted that “Turkey dreams of influence in Mosul,” and that “When ISIS destroyed the border between Syria and Iraq and declared the end of the British-French agreement that dismembered the Ottoman Empire, everything was up for grabs.”

According to journalist Yerevan Saeed, the neo-Ottoman desire to reassert Turkish control over Mosul extended toTurkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan personally.

Financial considerations also played a role in Ankara’s desire to see Mosul fall. In June 2014, just as ISIS was invading Mosul, Turkey signed a 50-year deal with Iraqi Kurdistan’s leaders, allowing them to export Kurdish (Iraqi) oil to the world.

The deal would allow Turkish firms to purchase and resell the oil without the legally-required consent of Baghdad, shipping it out of the Mediterranean Turkish port of Ceyhan to Israel, which was desperate for an additional reliable energy source. Turkey would also receive transit revenues for the movement of oil through the pipeline.

Kurdish export of oil through Turkey was opposed by Maliki and the Iraqi central government however, drawing the ire of Turkish politicians from Erdogan’s AKP party.

To bypass the central government, Kurdish authorities needed to control Kirkuk, which would give them not only access to vast additional amounts of oil, but also to the infrastructure needed to export it through Turkey, both of which would lay the foundation for a viable future independent Kurdish state.

Kurdish collusion

This problem was overcome, when, during the chaos of the ISIS invasion of Mosul, Peshmerga units immediately moved to occupy oil-rich Kirkuk, which they viewed as the “Kurdish Jerusalem.”

This increased Kurdish oil reserves by 9 billion barrels and allowed Kurdish access to the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline to export oil to Turkey. Kurdish authorities could now export oil regardless of opposition from Baghdad, and had the industrial base needed to potentially become an independent country.

Erdogan and his family directly benefitted financially from the export of Kurdish oil, as both his son Bilal and son-in-law, Turkish Energy Minister Berat Albayrak, owned firms involved in the oil trade.

The Jerusalem Post reported that by August 2015, roughly 77 percent of Israel’s oil supply was being imported from Iraqi Kurdistan via the Ceyhan port, leading the paper to comment that, “In short, while Turkey maintains its strong anti-Israel stance for public consumption, it is daily providing Israel with thousands of barrels of oil and reaping the consequential rewards.”

Kurdish collusion in the ISIS conquest of new territory continued when the Peshmerga – supposedly tasked with defending Sinjar and the Nineveh plain – confiscated the weapons of the endangered Yazidi and Christian minorities, and then withdrew from both regions without notice, leaving both populations defenseless. This allowed ISIS to massacre and sexually enslave thousands of Yazidis and ethnically cleanse hundreds of thousands of Christians.

The sectarian scapegoat

Since the fall of Mosul to ISIS in 2014, Mosulis have been blamed for welcoming ISIS into the city as liberators. However, the city fell due to the actions of specific political elements in Mosul, led by then-Governor Atheel al-Nujaifi.

It was Nujaifi who facilitated the collapse of the Iraqi army, allowing ISIS to conquer the city virtually unopposed. Mosul’s residents then suffered for years under ISIS’ brutal fundamentalist religious rule.

Nujaifi did so as part of a plan to divide Iraq in the interests of foreign powers, most notably Turkey, whose leaders wished to expand their influence in Mosul and benefit from the export of Kurdish oil to Turkey and beyond.

In 2018, An Iraqi court sentenced Nujaifi in absentia to three years of imprisonment, seized his assets, and banned him from traveling abroad. He was charged with “communicating” and “collaborating” with Turkey on the infiltration of illegal Turkish military forces into northern Iraq.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News