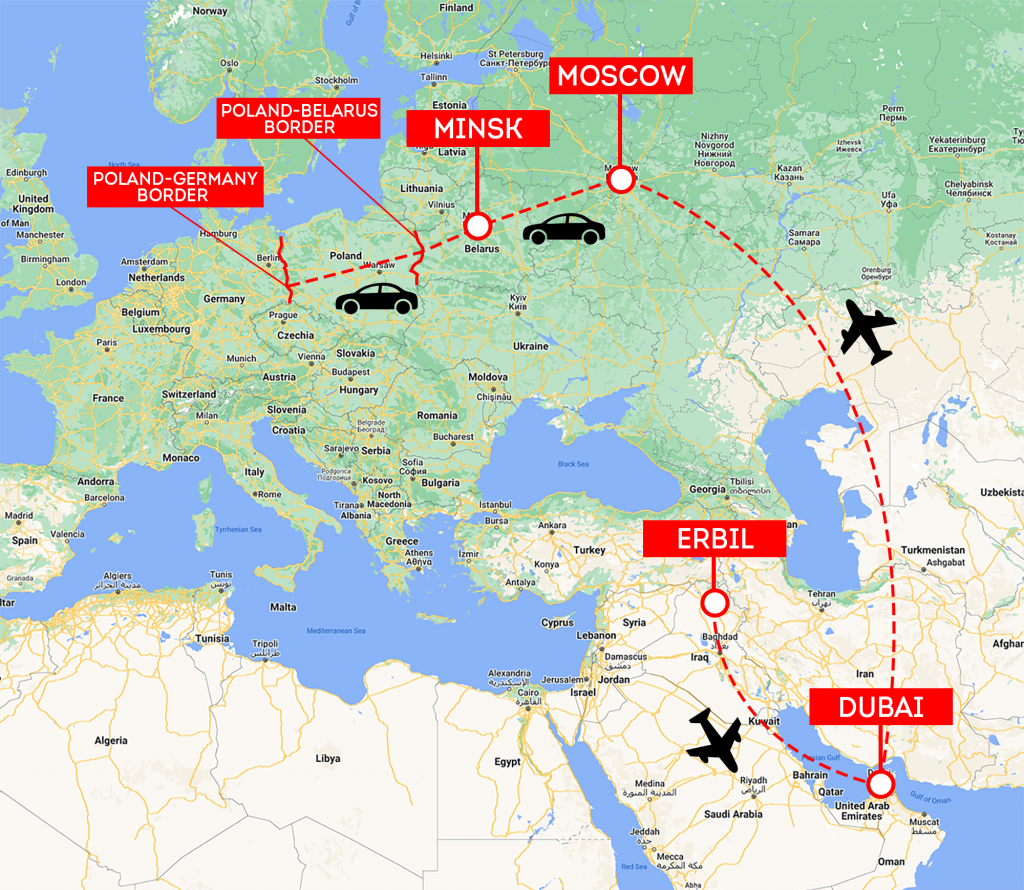

Migrants trying to enter the EU across its eastern borders are now travelling via a new route, taking them first to Russia then onto the Belarusian-Polish border, a BIRN investigation shows.

The 35-year-old S., originally from Syria, has been waiting for over a month in a hotel room in Minsk, unable to make his way into the EU after travelling on two planes and five cars to get from Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan to the Belarusian capital via Moscow.

“I’m just waiting and waiting for my smuggler to be in touch, I can’t make a move without him,” S. told BIRN via a WhatsApp chat on December 12, messaging from the room he has been sharing with nine other people.

S. landed at Domodedovo airport in Moscow, the Russian capital, on a flight from Erbil via Dubai in the early days of November.

The Russian visitor visa in his passport, which S. showed to BIRN, was issued in late October, valid for one month and allowing a single entry into the country (see below).

After landing in Moscow, S. got in touch with a smuggler who had promised to get him all the way to Germany.

S. is one of thousands of migrants who have been trying to enter the EU this year via a new variation of what Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, calls the Eastern Land Route. Rather than fly to Minsk, these migrants fly first to Moscow before travelling onwards to the Belarusian-EU border.

The reason for this detour is that towards the end of last year, in an attempt to thwart the migration crisis being orchestrated by Belarusian leader Aleksandr Lukashenko on the EU’s eastern borders, Brussels put pressure on third countries and international airlines to limit the number of flights bringing migrants into Minsk.

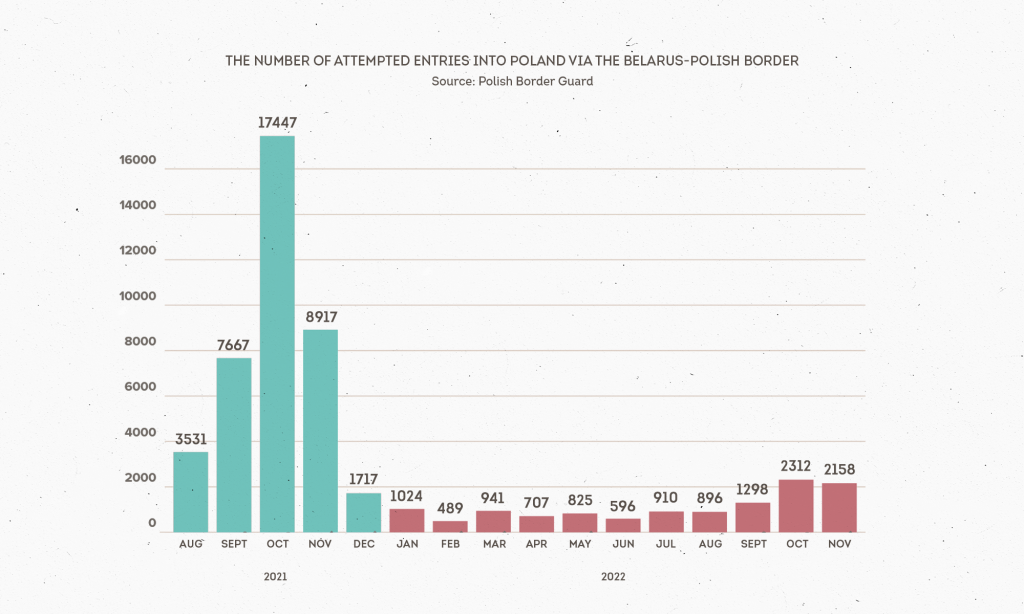

The intervention largely worked: according to data from the Polish Border Guard, from a peak of 17,000 in October 2021, the number of attempted entries into Poland via that border dropped to around 1,000 during the winter months of last year.

But by the summer of this year, Polish NGOs providing humanitarian assistance to migrants began noticing an increase in the number of migrants crossing the Belarus-Poland border that had Russian visas in their passports, rather than Belarusian visas as before. And the Polish Border Guard has now confirmed to BIRN that as many as 90 per cent of the migrants that tried to enter the EU via the Belarusian-Polish border this year were in possession of Russian visas.

While some could be residents of Russia fleeing a country at war or even potential forced conscription into the Russian army, BIRN can now show that many of these migrants are actually people trying to enter Europe via a new variation of the Eastern Route, through Moscow this time, which smugglers have been using to sidestep EU efforts to close the route.

Relying on interviews with migrants, travel agents selling Russian visas, smugglers guiding migrants from Moscow to the EU border, as well as documents provided by these actors and online information posted by travel agents and smugglers, BIRN can, for the first time, show how the new variation of the Eastern Route works.

Upon reaching Moscow, S. spent two days in the Russian capital before his smuggler sent a car to pick him up and drive him towards Belarus. He said it took his group about 12 hours to reach Minsk, about 700 kilometres away, and they had to change five different cars along the way.

Once in the Belarusian capital, S. embarked on a journey familiar to tens of thousands of migrants who have been trying to enter the EU via the Belarus-Polish border since the summer of 2021: getting to the border, trying to cross, getting pushed back into Belarus, trying again, and again, and again…

“The last time we reached the Belarusian border fence, after spending three days in the forest and sleeping under the snow, the Belarusians caught us, beat us and stole everything from us – money and personal items,” S. described his second attempt to cross into Poland.

“This road is very difficult,” he said. “We call it the road of death because, really, we have seen death up close along the way.”

Nevertheless, whenever the smuggler finally calls, S. said he will be ready to try for a third time.

In Russia for ‘medical treatment’

The advertisements from travel agents selling visas to Russia are all over Facebook, targeting Iraqis and many others across the Middle East. Some just show a picture of a visa to Russia and give a contact phone number; others are more abstract, for example including a photo of a golden autumn scenery and a promise of “medical treatment in Russia” (see below).

Yet others offer very specific information about the services they can deliver for their clients. One travel agency, for example, has been posting since early November photos of its clients having reached airports in Moscow (see below).

H., an independent travel agent, posted examples of visas and invitation letters he had helped obtain (see below).

Under the guise of being a migrant looking to obtain a Russian visa, a BIRN reporter spoke on the phone to two such independent travel agents operating in Iraq, which we will identify by their initials, H. and B.

The two offered similar packages: for between 2,500-3,000 dollars, they would organise Russian visas within a month of providing the passport information: if the migrant is younger, they would provide a student visa; if older, a visitor one.

For each of these types of visas, an invitation or sponsorship letter from Russia is needed: from a university in the case of the student visa; from a hosting individual in the case of the visitor visa.

Migrants then purchase the plane ticket independently (flying from Iraq via Dubai at the time of writing), but the travel agency promises they will be met at the airport by the Russian providing the invitation letter that established grounds for the visa to be issued.

As can be seen from the travel agency social media posts above, it can happen that the same Russian individual acts as “the receiving Russian friend” for multiple migrants provided with visas by the same travel agent.

Prior to departure, the migrant deposits the payment either with a trusted person or with a specific currency exchange office. The travel agent cashes it once confirmation has been received that the migrant has arrived at the airport in Russia.

Both H. and B. promise to help get the migrant all the way to Germany, by putting them in touch with smugglers that handle the Moscow to Germany part of the trip. H. quoted a total price of 6,000 dollars for the entire trip from Iraq to Germany.

Asked specifically about which routes are used to get into the EU, both H. and B. were adamant it was via Belarus.

“Kaliningrad is difficult, I cannot work there,” B. replied when asked about a potential Moscow-Kaliningrad-Poland route, which the Polish authorities fear might be opened by Russia in the near future. This has motivated the Poles to build a barbed wire fence on the Polish-Kaliningrad border.

“In Kaliningrad, there are specific places you cannot enter, and if you do so by mistake, the Russian person who helped you secure the visa would be punished,” B. said, even claiming to have personally been to the Russian exclave to check out the situation there.

Meanwhile, H. advised that trying to get to the EU via the Russia-Finland border was more complicated and demanding than via Belarus, making the latter route preferable.

The two conversations with the travel agents took place on December 5. Based on current practices in smuggling identified by BIRN, it does not seem that the Kaliningrad route is active at the moment of writing.

Hi-tech smugglers

Once a migrant arrives in Moscow, their onward travel is guided by a smuggler, normally a different person to the travel agent organising the visa – although the smuggler may be “sub-contracting” the travel agent, who attracts the clients and in turn recommends the smuggler.

Interestingly, in the case of the Middle Eastern migrants we are following in this story, the main smuggler is himself based in the Middle East and works remotely by using local drivers and smugglers that he hires in Russia, Belarus and further west.

M., the Syrian smuggler BIRN spoke to on December 6 by calling his Turkish phone number, was even broadcasting on Telegram a video with live GPS of a car apparently taking a group of migrants he had organised across the Polish-German border. The video shows the mobile pin advancing towards the border near the Polish town of Zgorzelec and German town of Gorlitz (see below a still from the video posted on Telegram).

In other videos posted by M., groups of migrants are filmed getting out of cars after allegedly reaching Germany, with the purported date of arrival visible on the video as proof that the smuggler is continuously delivering people to Germany.

When a BIRN reporter called under the guise of being a migrant in Moscow who needs to get to Germany, M. promised he could organise a car soon. For 400 dollars, a car would come and drive the migrant to Minsk, he said. In Minsk, there would be a wait of a few days until a larger group is organised, the smuggler said, and then it would cost another 4,500 dollars to be brought into Germany.

Both the smuggler and the travel agents BIRN spoke to claim they can provide a trip all the way to Germany. However, as S.’s experience demonstrates, the journey is often far different in reality.

The smugglers are able to bring the migrants from Moscow to Minsk, and then guide them to the Belarus-Polish border. But nobody can guarantee the migrants will be able to successfully get cross the border on the first, second or succeeding attempts.

At the time of writing, a 5.5-metre border wall runs about 200 kilometres along the Polish-Belarus border, complete with motion sensors and cameras. For the past year and a half, the Polish Border Guard has systematically pushed back migrants they apprehend crossing the border, regardless of age, nationality or health.

Prices vary. H., the travel agent, says the Moscow-Germany leg costs 3,000 dollars, while M., the smuggler, asked for 4,900 dollars to take a migrant already in Moscow to Germany. S., the Syrian migrant, told BIRN he is paying 7,000 dollars to get from Moscow to Germany.

“Do not even think about going unless you have 10,000 dollars,” said M., an Iraqi migrant waiting in Erbil for his Russian visa before embarking on the journey. “Once you get to Russia, you have to keep going.”

As S.’s experience shows, migrants are also subject to violence and theft by the Belarusian border guards or soldiers – allegations made by many who have tried to cross the Belarusian-Polish border since the summer of 2021, including those interviewed by BIRN.

Furthermore, even if migrants do manage to cross the border into Poland, the Polish police might still arrest them in cars on their way to Germany and return them over the border into Belarus, according to testimonies of migrants since the start of the crisis in 2021.

Then there’s the risk of death. On December 5, the burial of a 21-year-old Sudanese man, Sidding Musa Hamid Eisa, who died in early October on the Polish-Belarusian border, took place in Poland. The number of fatalities on the border is unknown, but it certainly surpasses 30. According to NGOs, around 200 people are currently considered missing, with families and friends searching for them.

In spite of all these risks, many feel they have no choice but to make the perilous journey: whether escaping war, instability or poverty, most of these people have little possibility of legally migrating to Europe.

According to the Polish Border Guard, there were over 2,000 attempted entries via the Belarus-Polish border in each of October and November this year.

“I am not a tree,” S. said referring to his trip, despite knowing of the potential dangers that lie ahead. “If a place doesn’t give me what I deserve, then I must change my place.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News