The change in Czech president foreshadows a prospective turn in the country’s inconsistent approach toward Kosovo, which has been characterised by the long-term clash between the outgoing pro-Serbian president and the government policy of recognition.

The day after Czechs elected their new president, the fourth in the country’s post-1989 democratic history, the outgoing president, well known in the Western Balkans for his pro-Serbian agenda, travelled to Belgrade for his last but one foreign visit to meet President Aleksandar Vucic and express once again his personal sympathies toward the Serb nation.

Petr Pavel, who will replace Milos Zeman in March, ran his successful campaign for the presidency as the antithesis of Zeman, whose two terms were marked by strongly pro-Chinese and pro-Russian rhetoric. Pavel, a veteran of the Balkan peacekeeping missions who concluded his career as chief of the Czech Armed Forces and chairman of the NATO Military Committee, stood in clear opposition to Zeman’s political style, portraying himself as a cultivated, consensus-seeking and clearly pro-Western candidate.

The upcoming fundamental change in the presidential office will thus bring a change of tone in many spheres of Czech politics, including the foreign policy area. Czech relations with Kosovo, which have been tainted by Zeman’s pro-Serbian agenda, should be one of the issues where this change will have an instant, direct impact.

Kosovo as point of conflict in Czech domestic politics

Western Balkan politics has only rarely found itself at the heart of Czech political debates. Nevertheless, the question of Kosovo’s statehood has repeatedly been a subject of domestic political polarisation.

The “Kosovo issue” developed into a political symbol of division, where Czech politicians regularly clashed over Prague’s international position with presidents playing a leading role.

Since the 1990s, all three Czech presidents while in office strongly followed their own proactive policies on Kosovo. However, the presidential agendas were frequently at odds with the positions of the concurrent Czech governments, which were primarily responsible for formulating foreign policy.

The first clash between the president and government over the issue came at the very outset of the critical period of conflict escalation that culminated in NATO’s intervention in 1999. Eventually, alignment with the Western policy advocated by then-president Vaclav Havel prevailed over a restrained position held by then-prime minister Milos Zeman and Parliamentary Speaker Vaclav Klaus, leaders of the two major political parties who both later became presidents.

After Kosovo‘s declaration of independence in 2008, the political rift re-emerged in a conflict between the president and government about recognition. Yet the roles had become intermingled, as Vaclav Klaus had meanwhile become president while the pro-Kosovo position was being advocated by the government.

The government recognised Kosovo’s independence and established diplomatic relations a few months later. However, Klaus used his limited executive powers to refuse to appoint a Czech ambassador to Pristina, thus setting the ground for a parallel presidential policy of non-recognition, which has continued to this day.

Vucic’s loyal non-recogniser

The outgoing President Zeman, who in his capacity as prime minister in 1999 reluctantly authorised the NATO intervention in Serbia on behalf of the Czech Republic, turned into a vocal advocate of Serbia for the remainder of his political career.

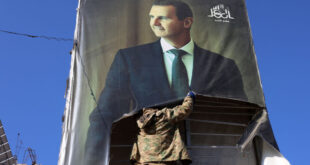

Zeman not only followed the presidential line of passive non-recognition set by his predecessor Klaus, but moved further towards active lobbying for the Serbian position. During his meetings with Serbian President Vucic, Zeman repeatedly employed provocative anti-Kosovar rhetoric that directly contradicted the official balanced positions of the Czech government.

When visiting Belgrade in 2019, Zeman told Vucic that he “doesn’t like Kosovo” and he would propose the Czech government withdraw its recognition of Kosovo. The president then put pressure on the prime minister at the time, Andrej Babis, in this regard. The opposition Communist Party even took the issue up in a parliamentary session, but the government quietly stuck to its policy of recognition.

After failing to alter the country’s official position, Zeman used Vucic’s visit to Prague in 2021 to express his “personal apology” for Czechia’s participation in the 1999 NATO intervention.

Zeman’s anti-Kosovar activism earned him loud ovations from Vucic’s regime, but called into question the consistency of Czech policy in the broader Western Balkan region. Analysts labelled the ambiguous position on Kosovo as that of a “reluctant and disengaged recogniser”, and Czech policy in the region has been widely seen in the context of an internal dispute taking place over Kosovo.

Pavel’s Western Balkan links from the past

The newly elected president is a newcomer to politics; Pavel spent his whole professional life in the military, starting in the army of communist Czechoslovakia in the 1980s and concluding in the highest ranks of the professional Czech Armed Forces and NATO structures in the 2010s. But both his military career and recent political rise have important links to the Western Balkans that gives clues to his prospective stance on the sensitive Kosovo issue.

In the early 1990s, Pavel kickstarted his military career with his deployment to the UNPROFOR peacekeeping mission in Croatia. During one of the Croatian counter-offensives against Serb forces in the Benkovac area, he led an operation to save 55 French peacekeepers trapped between the front lines.

The dramatic events of 1993 in Croatia were a central plank of Pavel’s successful presidential campaign and attracted considerable media attention. The candidate himself frequently pointed to his service in former Yugoslavia, establishing it as one of the cornerstones of his public image.

When reflecting on the ethnic conflicts in the Balkans in the 1990s, Pavel has used balanced diplomatic language in media interviews. He has pointed not only to war crimes committed by all sides, but also to failures by the international community and its peacekeepers on the ground.

When asked directly about the legitimacy of the NATO air campaign against Serbia in 1999, he cautiously advocated Western intervention in the context of previous Western failures in the region. As he explained in a pre-election TV interview, Western policymakers “still had the images from Srebrenica in front of them and did not want to see it happen again in Kosovo.”

Implications for the Czech position

Under the Czech political system, the president is allocated rather a representative role in the foreign policy field where the government and the Foreign Ministry bear the primary executive responsibility.

Pavel already announced that, unlike Zeman, he will take a more restrained approach and closely coordinate his steps in the foreign policy sphere with the current government. The Czech position towards Kosovo is one of the issues where such a shift to a ‘normal’ approach could bring substantial change.

Based on his previous experience and statements, it is clear that Pavel will be the first Czech president who will not openly question the independence of Kosovo since its declaration in 2008. Even more importantly, for the first time since the late 1990s, the Czech government and president will presumably follow the same line on the potentially divisive regional issue.

One of the few practical political steps that Pavel can actually take within the scope of his limited executive powers as a president is to appoint the first Czech ambassador to Pristina. This symbolic gesture would be a signal that Czechia is leaving behind its ambiguous position of “reluctant and disengaged recogniser” and is instead heading towards normalisation of bilateral relations with Kosovo.

Prospectively, such a change to ‘normal’ would lay the ground for a consistent approach to the resolution of the Kosovo-Serbia dispute and a less confusing Czech policy in the broader Western Balkans.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News