Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has entered its twelfth month. Reporting on the conflict understandably focuses on the day-to-day fighting and destruction, but it is important for Americans and U.S. policymakers to understand the larger issues raised by the war and the U.S. role in it. The following Defense Priorities analysis aims to improve understanding of these issues and what U.S. policy should prioritize as the war continues.

Map of Ukraine and contested territories

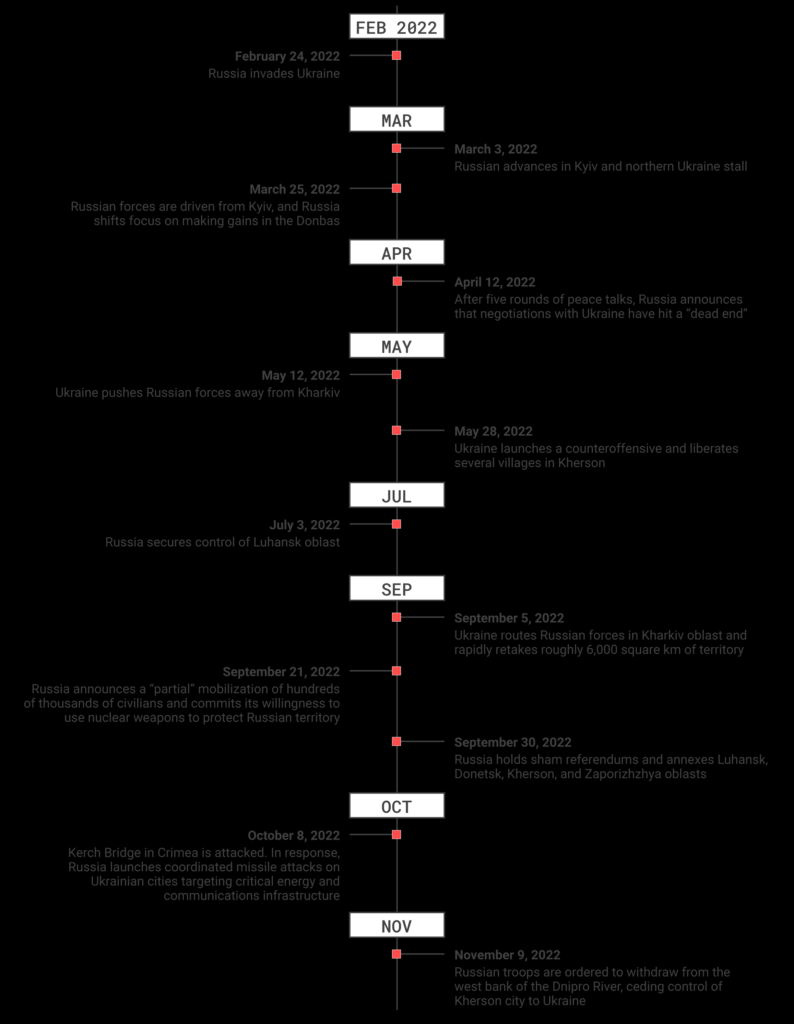

Major events of the Russia-Ukraine war

Russia bears responsibility for invading Ukraine

Russia bears responsibility for invading Ukraine. There is no confusion about who is at fault here. Russia’s aggression should, moreover, be condemned. Its invasion of Ukraine is an unjustified preventive war, which will likely prove a strategic failure, even if the Russian military manages to eke out something they can package as a victory.

American sympathies are appropriately with Ukraine, the victim. But focused, strategic thinking about U.S. interests—rather than emotions—should guide U.S. policy. There is danger of ill-considered actions that could escalate the conflict, and increase costs and risks to the U.S., Europe, and even Ukraine.

Despite its sympathy, the U.S. has no vital security interest at stake in Ukraine. Ukraine is more than 5,000 miles from the U.S. and is not a NATO ally. The U.S. imperative is to avoid a military clash with Russia which could go nuclear.

U.S. aid for Ukraine should therefore conform to humanitarian principles and embrace opportunities to help end the war if they arise. The U.S. should not forgo diplomatic openings for a resolution to maximize harm against Russia.

Russia limited its objectives after it failed to take Kyiv and concentrated its ground assault in eastern Ukraine. Russia has achieved some military success in the Donbas, capturing the Luhansk region in early July and accelerating military operations in Donetsk. But it is unlikely it can anytime soon launch further offensives, toward Kyiv or otherwise. If it tries, it may well find victory pyrrhic and become bogged down in a war of occupation. This would likely further unite Europe against Russia, harm Russia’s economy, and add to the costs of its strategic failure.

The invasion was a mistake by President Vladimir Putin. It reduces Russia’s ability to threaten other nearby powers. This is a minor bit of good news amid a needless, tragic war.

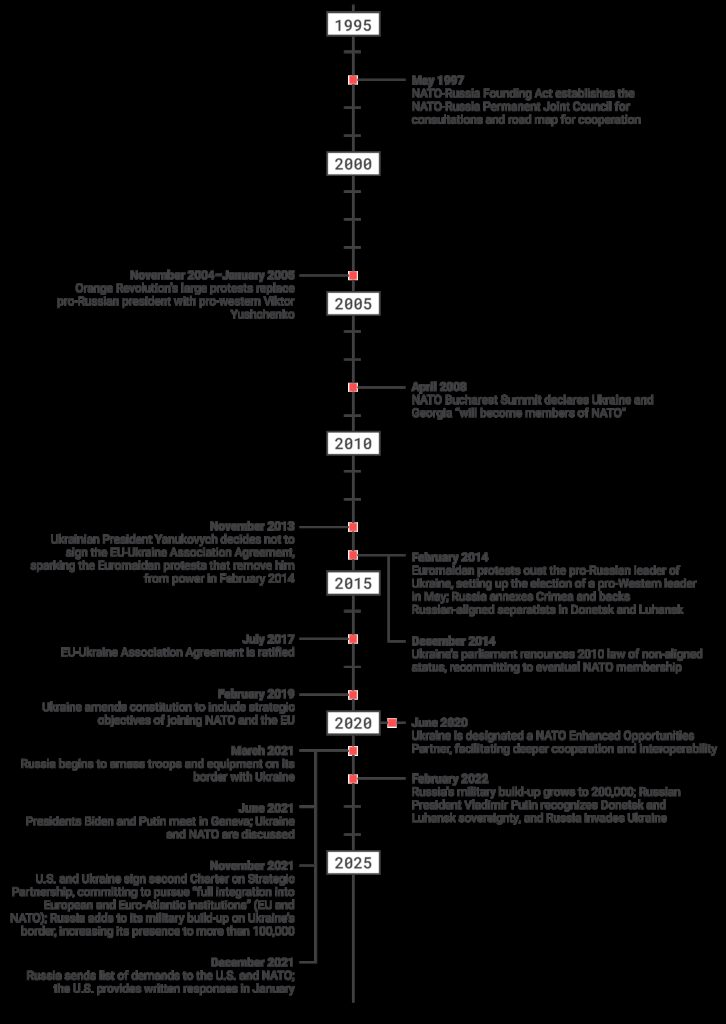

Timeline of key NATO-Ukraine events

U.S. and Europe’s responses should prioritize containing escalation risks

- U.S. efforts to help Ukraine should be governed by the reality that escalation to a NATO-Russia war could present severe risks: cyberattacks, energy shortages, economic dislocation, brutal conventional war, and (even though remote) nuclear exchanges that result in massive casualties.

- Though some argue for “regime change” to oust President Putin, Russia is not about to transform into a democracy. Efforts to change Russia’s government are likely to fail, while rhetoric about changing it will further increase anti-western sentiment within the Russian government. That, in turn, could impel Russia to scale up the war, resulting in the death of many more Ukrainian civilians.

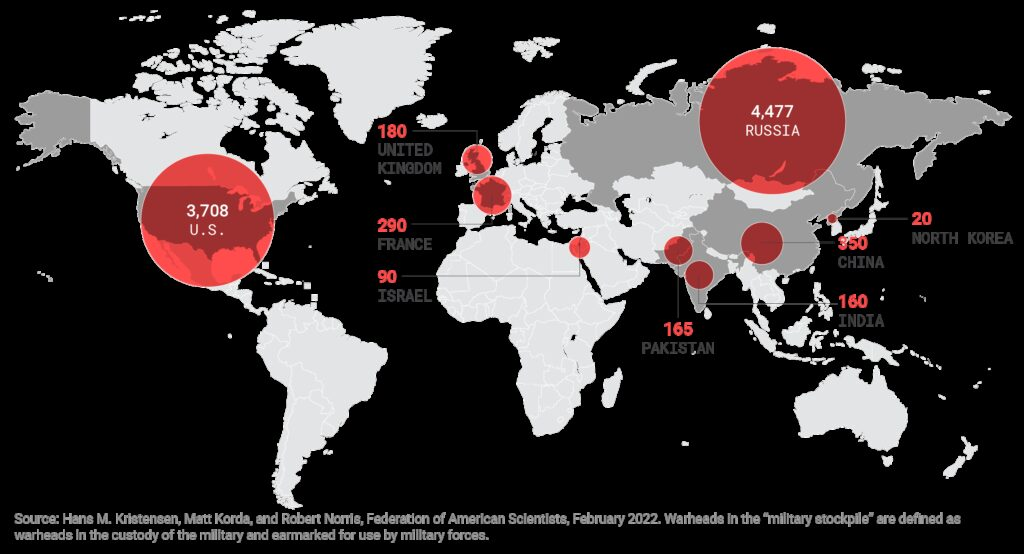

- Any successor to President Putin is not likely to be more friendly to the West or more democratic. Most importantly, efforts to change Russia’s political system could lead to instability, even violent conflict, in a country with the world’s largest nuclear stockpile.

- The U.S. should eschew talk of regime change in Russia and weakening Russia beyond stopping its invasion of Ukraine. Such talk is counterproductive and in tension with efforts to push for a settlement to halt the carnage and spare Ukraine from a longer, more brutal war. Instead, the U.S. should state clearly that sanctions and other punishment will end when the invasion does and that it is open to supporting Ukraine’s neutrality.

NUMBER OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS IN EACH COUNTRY’S MILITARY STOCKPILE

The U.S. and Russia hold nearly 9 of every 10 deployed and stored nuclear warheads in the world. Avoiding a nuclear conflict remains the highest U.S. national security priority.

- While the probability of nuclear war between Russia and the U.S. is low, the U.S. should avoid steps that increase it. Russia has a stockpile of approximately 4,477 nuclear warheads and the U.S. around 3,708—together more than 85 percent of the world’s total.

- On February 27, President Putin ordered Russia’s nuclear forces into “special combat readiness.” On March 2, the Pentagon announced Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin wisely postponed a Minuteman III ICBM missile test launch scheduled for later in the week. Steps should continue to avoid misunderstandings that could lead to miscalculation.

- The Biden administration rightly ruled out deploying U.S. troops to defend Ukraine and avoided other reckless steps, such as establishing a no-fly zone.

- A no-fly zone would require enforcement: shooting down Russian airplanes and suppressing S-400 air defense systems inside Russia’s borders. That would risk war between NATO and Russia and amount to madness. President Putin has said of any third party creating a no-fly zone over Ukraine, “That very second, we will view them as participants of the military conflict.”

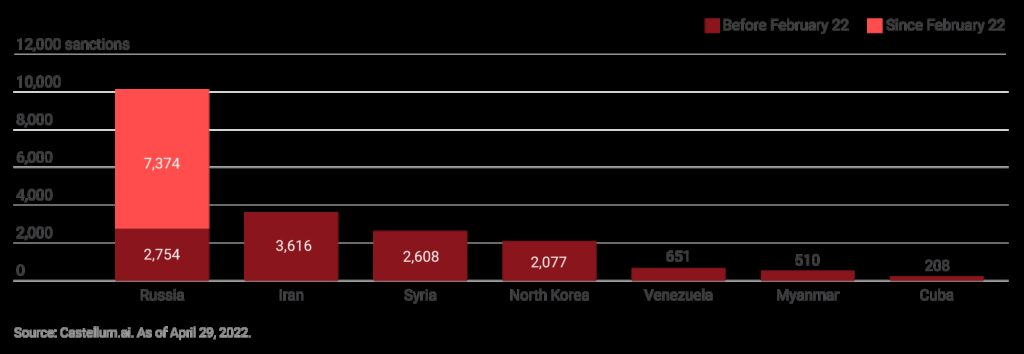

The U.S., Europe, and other nations imposed broad and severe sanctions on Russia

Extensive sanctions imposed on Russia by the U.S. and its partners significantly harmed its economy and, over the long term, its ability to develop and deploy military capability. But it is not likely to stop Russia’s invasion.

Sanctions to punish or change behavior—what is their purpose and likely effect?

- Given the risks of triggering a nuclear war, the U.S. military will not fight to defend Ukraine against Russia, so the U.S. is limited in how it can respond: principally diplomacy to hasten a settlement, military aid to Ukraine to defend itself, and economic sanctions to punish Russia and encourage it to end its invasion.

- The costs and risks the U.S. and its partners are willing to assume to support Ukraine narrow the military options. Similar constraints—the risks from escalation—limit the ability to conduct all-out economic warfare against Russia.

- Western sanctions are inflicting severe economic pain on Russia, although their effect on Russia’s military is limited. The blowback from these sanctions has also harmed the global economy, including the West: Oil prices rose, as did costs for air freight (following a Russian ban on overflights by the aircraft of 36 countries), and container and tanker shipping, all contributing to growing inflation.

- Higher oil prices—already at their highest level since mid-2014—will further reduce economic growth and increase inflation, to the detriment of Americans. The EU will end imports of sea-born Russian crude oil by the end of 2022, putting additional upward pressure on global prices.

- The economic fallout is widespread. Russia and Ukraine together exported around a quarter of the world’s wheat in recent years. The invasion has curbed exports and driven up food costs in medium- and low-income countries. Egypt, Indonesia, India, and other countries face greater economic stress and food insecurity, which could lead to political turmoil.

- Inflation is increasing in the West as fuel and food prices rise following Russia’s invasion. The U.S. Federal Reserve is raising interest rates to fight inflation, which will slow economic growth and could trigger a recession.

- Higher interest rates will also increase borrowing costs, and therefore debt, particularly for low-income countries, which are already highly debt-burdened. That, in turn, raises the risks of defaults on debt payments.

- Punitive zeal regarding sanctions unmoored from an understanding of harmful and unintended, even unforeseen, consequences may backfire, not just by encouraging Russian retaliation, but also by impoverishing ordinary Russians and increasing their hostility toward the West.

- Sanctions, like any other policy, should focus on outcomes. Studies show they cause economic harm and punish a targeted country, but they rarely change its actions, particularly great powers. This is doubly true when the desired change affects the targeted country’s vital security interests, as Russia views its war against Ukraine.

- The effectiveness of sanctions derives from the expectation that they will be eased or removed if the targeted state changes its behavior. Some sanctions may be warranted merely as punishment—but most sanctions should be tied to a clear, realistic strategy.

- The U.S. and its partners should state clearly they will cease sanctions on Russia in exchange for specific and verifiable steps. Otherwise, the effectiveness of sanctions will be undermined.

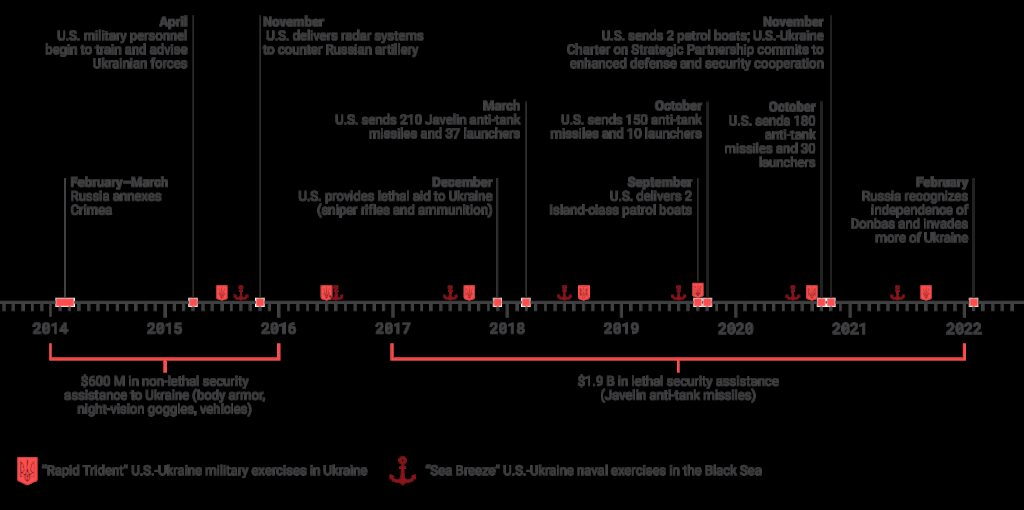

Key U.S. military aid to and training in Ukraine before Russia’s invasion

For years before Russia’s invasion, the U.S. sent military aid to and conducted military exercises in Ukraine.

Military aid and the balance of forces

- Since late 2017, the U.S. has provided lethal military aid to Ukraine, including Javelin anti-tank missiles. Between 2014 and 2021, the U.S., U.K., Denmark, Canada, Poland, France, Turkey, U.A.E, and a few other countries provided Ukraine with military vehicles and equipment such as armored personnel carriers, patrol craft, and unmanned aerial vehicles.

- Since Russia’s invasion in early 2022, more than 20 countries—including Germany, Finland, Norway, and Sweden—have delivered or announced their intentions to send anti-tank missiles and other weapons and ammunition to Ukraine.

- The U.S. has committed more than $27.1 billion in military aid to Ukraine since Russia’s invasion began. On January 25, 2023, the Pentagon announced a commitment of 31 M1A2 Abrams tanks for Ukraine, funded through the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative.

- In addition to the 31 M1A2 Abrams tanks sent by the U.S., Ukraine will also receive 14 Leopard 2 Tanks from Germany, 14 British Army Challenger 2 tanks from the United Kingdom, 14 Leopard 2 Tanks from Poland, and 60 additional Polish tanks: 30 PT-91 Twardy tanks and the remainder being upgraded Soviet-built T-72 tanks.

- Reports suggest it could take months, if not a year or more, for the tanks to arrive in Ukraine, dashing any hope of an immediate impact on battlefield realities. Further, equipping Ukrainian forces with the skill set and integrated operations training necessary to translate the equipment into an offensive advantage could require up to an additional year of training by NATO forces in Germany or elsewhere.

- The benefits of supporting Ukraine’s defense should be weighed against the risk of pointlessly prolonging the war by encouraging Kyiv’s hope that it can militarily eject Russia from its all territory without having to endure an unpleasant diplomatic settlement. Limiting what arms the U.S. provides Ukraine is a reasonable compromise between these dangers.

- President Biden appears cognizant of the risks of providing weapons that could strike Russia, like long-range drones and attack aircraft, and has provided 16 HIMARS units on the condition that the rocket systems would not be used for cross-border attacks. On September 28th, the Pentagon announced they would be sending 18 additional HIMARS units to Ukraine. However, these HIMARS won’t be delivered immediately and could take a few years to deliver, according to a Pentagon official.

- HIMARS, with its superior range, precision and reload rate compared to Russian and Ukrainian equivalents, has been very effective at destroying Russian targets. HIMARS started service in Ukraine on June 25th, and by July 16th at least 30 Russian logistics hubs had been destroyed. A week later, the Pentagon reported over 100 high-value targets being hit.

- After weeks of warning it would view supply lines of military aid from the West as legitimate targets, Russia in early May began ramping up attacks on the Ukrainian rail network. These attacks could be a precursor to more fulsome attacks on military supply lines from NATO members, potentially drawing the alliance further into the war.

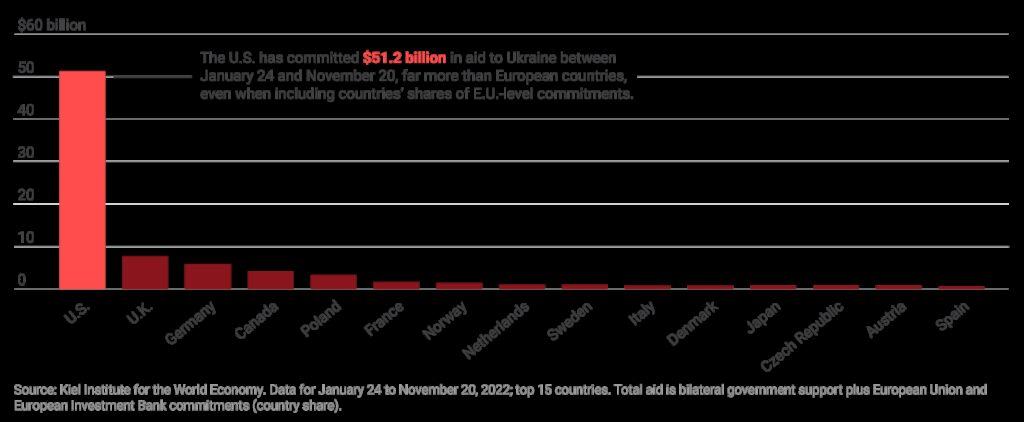

Total government aid to Ukraine AS Of NOVEMBER 20

U.S.-provided aid to Ukraine surpasses that provided by European countries, even though western Europe has far greater interests in eastern Europe.

Europe can and should shoulder more of the burden of balancing Russia and deterring its aggression

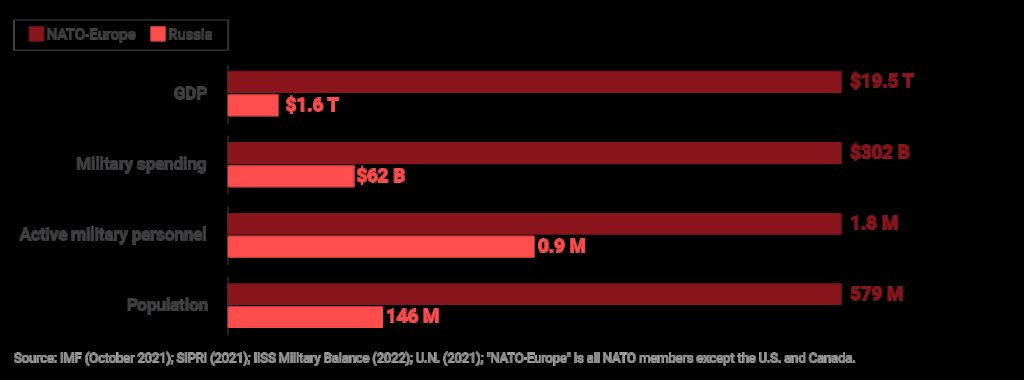

- Russia’s invasion revealed its conventional weakness—and it is getting weaker from waging this war. Its failure demonstrates the military balance of power is more favorable to NATO-Europe than it seemed and has spurred European states to increase military spending and deepen their own defense cooperation.

- Germany announced a one-time increase in its military budget of more than $110 billion and renewed its commitment to spend more than 2 percent of its GDP on defense annually, a pledge NATO members made at the Wales Summit in 2014, along with a commitment to spend more than 20 percent of their defense budgets on major equipment.

- The leading European powers, most of all Germany and France, should take far more responsibility for countering the Russian threat and reduce their dependence on the U.S. military. The increased apprehension about Russia in Europe offers an opportunity to move toward strategic autonomy, which will require Europe to modernize its military power and address interoperability challenges.

- The primary security threat to Europe is Russia. Its attack on Ukraine has exposed weaknesses in the Russian military that remove doubt that it is incapable of dominating Europe.

- The 28 European countries in NATO have a combined GDP more than 10 times Russia’s and, in 2020, spent $302 billion on their militaries compared to Russia’s $62 billion ($178 billion in PPP). NATO-Europe fields 1.8 million active-duty troops compared to Russia’s 900,000, and it has a population nearly 4 times as large as Russia’s.

The history of NATO expansion raises the question of whether there was an alternative way of organizing Europe after 1989.

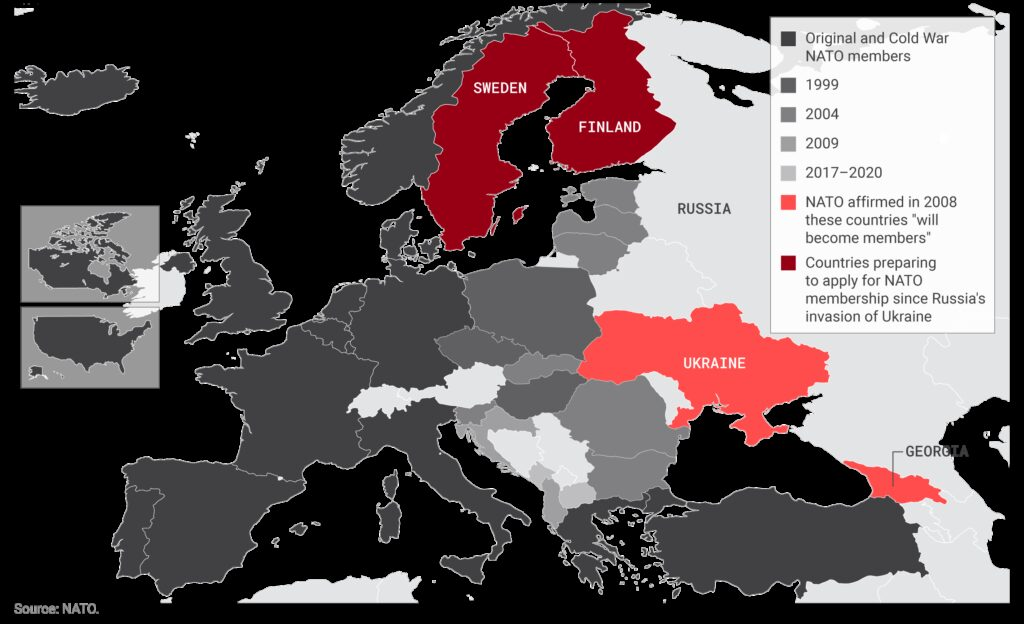

Considerations for the U.S. as Sweden and Finland bid to join NATO

- As a result of Russia’s invasion, Finland and Sweden formally applied to join NATO, a military alliance underwritten by U.S. nuclear weapons, on May 18th, and at the Madrid Summit, NATO formally invited Finland and Sweden’s membership. If these states join, they should be used to provide impetus to push the burden of European defense more onto Europeans.

- On August 3rd, the U.S. Senate voted to approve Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO. Seven NATO members have yet to approve Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO, but it’s highly likely both countries will join the alliance.

- Both Finland and Sweden possess capable militaries that could bolster NATO-Europe defense capabilities in some respects. But new members traditionally add to the defense burden and risk for leading members, like the U.S. That is especially a risk with Finland, given its 800-mile border with Russia (double NATO’s border with it) and small active military.

- The U.S. should avoid deploying forces to defend Finland, letting Europeans do so if they want, and use the added combat capability the new states add as impetus to reduce its role in Europe’s defenses.

The Balance of power between Russia and NATO-Europe

Resolving the Ukraine-Russia war

Ukraine’s resiliency has been remarkable. On September 6th, the Ukrainian Armed Forces launched a counteroffensive against Russian positions surrounding Kharkiv and Kherson concurrently.

Capitalizing on Russian Armed Forces shifting to the southern positions surrounding Donetsk, the Ukrainian Armed Forces made considerable territorial gains in the northern region outside of Kharkiv, with Ukrainian forces now positioned about 50km from Russia’s border.

On September 13th, as President Zelenskyy marked 200 days since Russia began its invasion of Ukraine and a week since the Ukrainian counteroffensive was launched, he claimed that the Ukrainian Armed Forces had taken back more than 6,000 sq km from Russian forces in the month of September.

The Ukrainian military also claimed to retake more than 20 settlements over the span of 24 hours, regaining control of key towns Izyum and Kupiansk.

The current lines of contact have remained fairly stable through the winter, with heavy fighting centering around the city of Bakhmut in the Donetsk Oblast.

While Ukraine has made clear its intention to expel Russia from all occupied Ukrainian territory, in a private briefing, senior Defense Department officials told the House Armed Services Committee that U.S. intelligence suggests Ukraine lacks the capacity, both now and in the near-term, to retake Crimea.

The Biden administration has reportedly softened its stance against supporting Kyiv in targeting the Crimean Peninsula, despite the increased risk of escalation with Russia, in hopes that threats against Russian control of the peninsula would strengthen Ukraine’s position in future negotiations.

Both sides believe their side will win and show no signs they’re willing to negotiate an end to the conflict. U.S. policy is designed to arm Ukraine so it can blunt Russia’s invasion and force them to settle, but it must also avoid risks of escalation, potentially to nuclear conflict.

Ukraine’s strength aids neutrality and insulates it from Russia’s influence

This war is clarifying the balance of power between Ukraine and Russia. Ukraine is demonstrating its ability to pursue fortified neutrality, maintaining independence from Moscow while never being able to escape the reality it shares a 1,200-mile border with Russia.

Russia’s mobilization and annexation are signs of desperation

- Russia’s mobilization of hundreds of thousands of draftees after long resisting such a step is an embarrassment and a sign of Russia’s desperation to hold territory in Ukraine amid successful Ukrainian offensives.

- Mobilization, along with Russia’s September announcement that it had annexed Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia oblasts in Ukraine, and recent attacks on Ukraine’s infrastructure, indicate that Russia remains committed to war.

- Combined with Ukraine’s stated commitment to regaining its territory, Russia’s escalatory steps means the war will continue indefinitely and may become more destructive and terrible for Ukrainians.

- Annexation, along with reminders that Russia nuclear doctrine reserves the use of nuclear weapons for the defense of Russian territory, creates stark new dangers.

- It is unlikely that Russia would use nuclear weapons, even the tactical or battlefield variety, against Ukrainian forces in defense of annexed territory—and more recent comments by Vladimir Putin indicate as much.

Nuclear risks mean the U.S. should continue to refuse direct involvement in Ukraine

- On November 15, a missile crossed Poland’s border, first believed to be Russian before confirmed to be from a Ukrainian air defense system. The possibility of nuclear use should be a sobering reminder for the U.S. of the need to stay out of direct participation in the war in Ukraine and to avoid threats that might draw in U.S. forces

- It is not credible that the U.S. would attack Russia and risk nuclear war over Ukraine after having refused to fight directly for it already, even if Russia uses tactical nuclear weapons.

- However, talk of attacking Russia and risking nuclear war for Ukraine might give Ukraine false confidence that they are under the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

- Ukraine should make their own decisions about the risk they run with offensives, but they should know they bear those risks, not the U.S.

- The Biden administration’s policy of telling Russia nuclear use would be catastrophic to its interests is sensible. This could be further augmented by statements saying Russian nuclear use in Ukraine will only create more U.S. support for Ukrainian forces—suggesting that using nuclear weapons will not bring Russia victory to undermine the case for doing so.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News