How ASEAN Survives—and Thrives—Amid Great-Power Competition

The defining geopolitical contest of our time is between China and the United States. And as tensions rise over trade and Taiwan, among other things, concern is understandably mounting in many capitals about a future defined by great-power competition. But one region is already charting a peaceful and prosperous path through this bipolar era. Situated at the geographical center of the U.S.-Chinese struggle for influence, Southeast Asia has not only managed to maintain good relations with Beijing and Washington, walking a diplomatic tightrope to preserve the trust and confidence of both capitals; it has also enabled China and the United States to contribute significantly to its growth and development.

This is no small feat. Three decades ago, many analysts believed that Asia was destined for conflict. As the political scientist Aaron Friedberg wrote in 1993, Asia seemed far more likely than Europe to be “the cockpit of great-power conflict.” In the long run, he predicted, “Europe’s past could be Asia’s future.” But although suspicion and rivalry endured—particularly between China and Japan and between China and India—Asia is now in its fifth decade of relative peace, while Europe is once again at war. (Asia’s last major conflict, the Sino-Vietnamese war, ended in 1979.) Southeast Asia has endured a measure of internal strife—in Myanmar especially—but on the whole, the region has remained remarkably peaceful, avoiding interstate conflict despite significant ethnic and religious diversity.

Southeast Asia has also prospered. As the living standards of Americans and Europeans have languished over the last two decades, Southeast Asians have achieved dramatic economic and social development gains. From 2010 to 2020, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), made up of ten countries with a combined GDP of $3 trillion in 2020, contributed more to global economic growth than the European Union, whose members had a combined GDP of $15 trillion.

This exceptional period of growth and harmony in Asia is not a historical accident. It is largely due to ASEAN, which despite its many flaws as a political and economic union has helped forge a cooperative regional order built on a culture of pragmatism and accommodation. That order has bridged deep political divides in the region and kept most Southeast Asian countries focused on economic growth and development. ASEAN’s greatest strength, paradoxically, is its relative weakness and heterogeneity, which ensures that no power sees it as threatening. As the Singaporean diplomat Tommy Koh has observed, “The U.S., China, and India are not able to take the role of driving the region because they have no common agenda. ASEAN is able to drive precisely because the three great powers cannot agree. And we can continue to do so as long as the major powers find us neutral and independent.”

ASEAN’s nuanced and pragmatic approach to managing geopolitical competition between China and the United States is increasingly seen as a model for the rest of the developing world. The vast majority of the world’s population lives in the global South, where most governments are primarily concerned with economic development and do not wish to take sides in the contest between Beijing and Washington. China is already making deep inroads across Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. If the United States wants to preserve and deepen its ties with countries in these regions, it should learn from the ASEAN success story. A pragmatic, positive-sum approach that looks past political differences and is open to cooperation with all will be more warmly received in the global South than a zero-sum approach that aims to divide the world into opposing camps.

PEACE AND PRAGMATISM

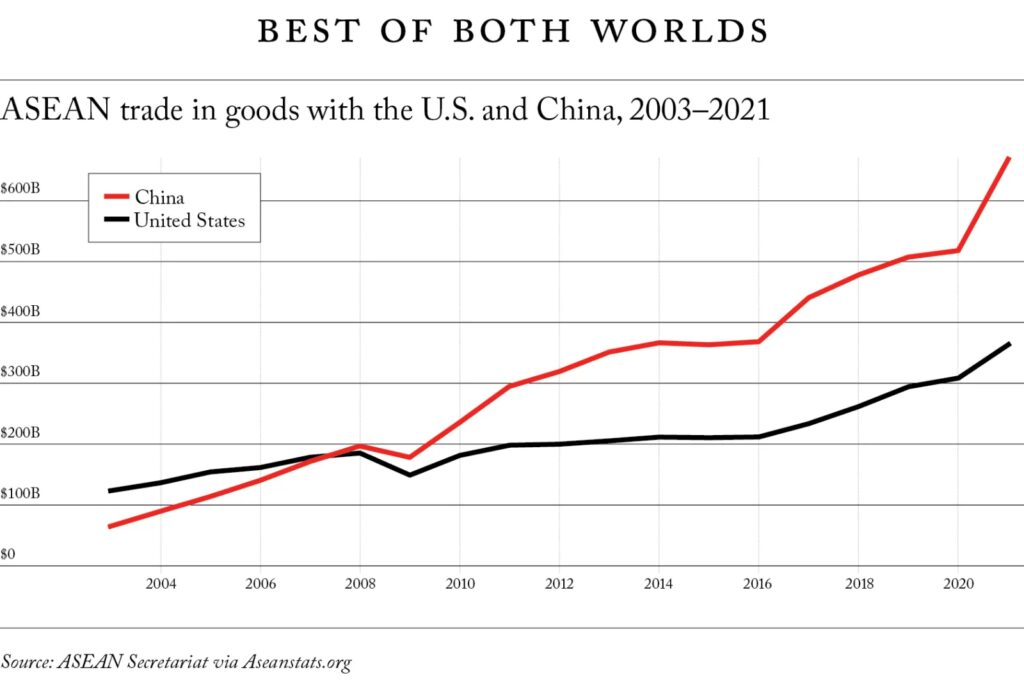

ASEAN was not always seen as evenhanded. Established with strong U.S. backing in 1967, the body was initially condemned by China and the Soviet Union as a neoimperialist American creation. But in recent decades, as China opened up its enormous economy, Beijing has embraced the regional bloc. ASEAN signed a free trade agreement with China in 2002, leading to a spectacular expansion of trade. In 2000, ASEAN’s trade with China was worth just $29 billion—roughly a quarter of the region’s trade with the United States. But by 2021, ASEAN’s trade with China had exploded to $669 billion, while its trade with the United States had increased to $364 billion.

Trade with both China and the United States has helped power ASEAN’s remarkable economic rise. The region’s combined GDP in 2000 was just $620 billion, an eighth of Japan’s. In 2021, it was $3 trillion, compared with Japan’s $5 trillion. And projections show that the ASEAN economy will be larger than Japan’s by 2030. Clearly, closer economic ties between the 680 million people who reside in ASEAN countries and the 1.4 billion people in China have delivered significant benefits to ASEAN. And this mutually beneficial relationship is just beginning. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership—a free trade agreement among Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and the members of ASEAN—came into force in January 2022 and will likely spur even more significant jumps in economic growth in the coming decade.

Even as it cultivates closer relations with China, ASEAN is determined to maintain equally close ties with the United States. U.S. President Donald Trump largely ignored Southeast Asia (as he did the rest of the world), but U.S. President Joe Biden has made a major effort to work with ASEAN, and its member states have responded enthusiastically. In May 2022, Biden hosted an ASEAN summit at the White House that was attended by most of the union’s key leaders. Later that month, the Biden administration launched its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, which aims to deepen U.S. economic engagement with partners in the region. Seven out of ASEAN’s ten countries signed on, together with Australia, Fiji, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea, demonstrating again that ASEAN wants to preserve its strong ties with Washington.

Geographic proximity to China inevitably means that ASEAN will have more challenges dealing with China than with the United States. Already, disputes have arisen over the South China Sea and Chinese 5G technology, among other issues. China contests the territorial claims of four ASEAN countries—Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam—but its conduct in the South China Sea disrupts relations with all association members. In 2012, for instance, China unwisely pressured Cambodia, then the chair of ASEAN, to exclude any mention of conflicts over the South China Sea from a joint communiqué following an ASEAN ministerial meeting. Indonesia was able to step in to resolve the impasse by brokering a common ASEAN position a week later. But Beijing subsequently mishandled its relations with Jakarta. Although the so-called nine-dash line on Chinese maps showing Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea runs close to Indonesia’s Natuna Islands, China had previously assured Indonesia that there were no overlapping claims. Yet in 2016 and 2020, Chinese fishing vessels entered Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone, prompting Indonesian President Joko Widodo to make high-profile visits to the Natuna Islands to reaffirm his country’s sovereignty over the region.

The ambiguous nature of the nine-dash line will likely remain an irritant in ASEAN-Chinese relations. So will the inability of both parties to conclude a long-awaited “code of conduct” agreement for the South China Sea that would reduce the risk of conflict in the disputed waterway. But it is also clear that the culture of pragmatism that envelops ASEAN-Chinese relations will prevent any major flare-ups. Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam have all increased their economic engagement with China, despite their disputed territorial claims in the South China Sea. In the past, China has also made pragmatic compromises with its smaller ASEAN neighbors, including removing two dashes from its original 11-dash line as a show of friendship to Vietnam in 1952. It would be wise for China to make similar pragmatic compromises in the future.

Another source of friction in ASEAN-Chinese relations is Washington’s global campaign against the adoption of Chinese 5G technology. The choice of a 5G telecommunications system is a national decision, so ASEAN has no collective position on whether its members should deal with Chinese telecom giant Huawei. Yet the union’s signature pragmatism has prevailed, with each member state making its own decision according to its needs. Indonesia and the Philippines have contracted with Huawei to build their 5G networks, while Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam have not. These decisions indicate that ASEAN countries consider American concerns but balance them against their own interest in having access to cheap technology that benefits their people.

Sometimes, those interests demand that ASEAN countries largely ignore American concerns. The United States has campaigned equally hard against China’s Belt and Road Initiative, but this campaign has essentially failed: all ten ASEAN countries have participated in various BRI projects, and the region as a whole has been among the most receptive to China’s mammoth infrastructure investment scheme. According to Angela Tritto, Albert Park, and Dini Sejko of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, ASEAN countries had launched at least 53 projects under the BRI umbrella as of 2020.

These projects have brought substantial rewards. Laos remains one of the poorest countries in the world, but thanks to the BRI, it now boasts a high-speed train linking the capital, Vientiane, to China’s Yunnan Province. With a top speed of 100 miles per hour, the sleek new bullet train cuts what was once a 15-hour road trip to under four hours, promising a new tide of trade and tourism from China. Indonesia also turned to China for help building a high-speed train from Jakarta to Bandung, a little more than 90 miles away. It could have purchased a train from any country in the world but chose China after Widodo took a rail journey of similar length in China in less time than it took him to finish a cup of tea. The United States simply has not put forward a viable alternative to the BRI, so the choice to embrace the Chinese initiative over American objections has been an easy one.

BELLWETHER OF THE GLOBAL SOUTH

ASEAN’s approach to managing geopolitical competition between China and the United States holds lessons for the rest of the developing world. As China deepens trade and investment ties with states across the global South, more and more countries are adopting a similarly pragmatic approach to balancing Beijing’s and Washington’s concerns. This should not come as a surprise. Many developing countries respect and admire ASEAN’s achievements and see the region’s experience as a guide.

As it has in Southeast Asia, China has cultivated deeper economic relations with Africa. Western countries, including the United States, have warned African governments to be wary of Chinese exploitation, but such admonitions have been met with skepticism, not least because of the West’s long and painful record of exploiting Africa. Moreover, the empirical evidence shows that Chinese investment has boosted economic growth and generated new jobs on a continent where jobs are scarce.

According to the development economist Anzetse Were, Chinese investment in Africa has grown at an annual rate of 25 percent since 2000. Between 2017 and 2020, Chinese investment created more jobs than any other single source of foreign investment and accounted for 20 percent of Africa’s incoming capital. And Chinese companies “are not in the business of just hiring their own,” as some critics have alleged, Were writes. “African employees make up on average 70 percent to 95 percent of the total workforce in Chinese firms.”

The United States simply has not put forward a viable alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative.

By comparison, the United States and other Western countries have offered mostly empty promises and inaction. For much of the last decade, U.S. foreign direct investment in Africa has lagged Chinese foreign direct investment by roughly half, and much of the development aid the United States delivers to the continent—like much Western aid in general—ends up in the hands of Western consultants and companies. As the journalist Howard French has observed, the United States has grown “increasingly stingy and scornful” about development assistance at the same time as China has “gotten into the global public goods game with both feet.”

Hypocritical moralizing about climate change, corruption, and human rights has also undermined the standing of Western countries in Africa. The United States and many European powers have long lectured Africans about the need to transition away from fossil fuels, but they suddenly stopped after Russia invaded Ukraine and they needed Africa’s oil and gas. By contrast, China has been less sanctimonious, delivering aid and investment without the burdensome conditions placed on Western aid. As Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta said in January 2022, “Our partnership with China is not a partnership based on China telling us what to do. It is a partnership of friends, working together to meet Kenya’s socio-economic agenda. . . . We do not need lectures about what we need, we need partners to help us achieve what we require.”

China has had similar success in deepening ties with Latin America. Between 2002 and 2019, total Chinese trade with Latin America and the Caribbean increased from less than $18 billion to more than $315 billion, according to the Congressional Research Service. By 2021, Chinese trade with the region had ballooned to $448 billion. That figure is still less than half of U.S. trade with Latin America, but 71 percent of U.S.–Latin American trade is with Mexico. In the rest of the region, Chinese trade has overtaken U.S. trade by $73 billion.

The growth of Chinese trade with Brazil, Latin America’s largest economy, has been particularly striking. In 2000, Brazil’s exports to China stood at $1 billion per year. Now, Brazil exports $1 billion worth of goods and services to China every four days. Some of this growth occurred during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, who was far closer to Trump than he was to Chinese President Xi Jinping. Even during the two years that Trump and Bolsonaro overlapped in office, Brazil continued to pursue deeper economic integration with China, suggesting that an ASEAN-like culture of pragmatism is taking hold in Brasília.

The Gulf is yet another region where China is making inroads. Traditionally, the oil-rich states of the Gulf have looked to Washington for protection. Yet close political and security ties with the United States have not prevented Gulf countries from deepening their economic ties with China. In 2000, trade between the Gulf Cooperation Council and China stood at just under $20 billion. By 2020, it had grown to $161 billion, and China replaced the EU as the GCC’s largest trading partner. During the same period, U.S. trade with the GCC grew much more modestly, from nearly $40 billion to $49 billion. In 2021, the GCC’s trade with China, at $180 billion, surpassed its combined trade with the United States and the EU.

The GCC countries have some of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world. Their decisions about where to invest are not driven by concerns about politics or a conception of friendship. They are driven by cold calculations about which region is likely to deliver the highest growth. In 2000, the GCC sovereign wealth funds were invested almost entirely in the West. That year, GCC countries accounted for less than 0.1 percent of foreign direct investment into China. But by 2020, most GCC sovereign wealth funds had significantly stepped up their investment in China, although exact investment figures are hard to come by because most of these funds do not disclose their holdings publicly.

Clearly, Gulf countries do not wish to compromise their relations with the United States—and with the Abraham Accords, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates arguably drew closer to Washington in 2020—but neither do they wish to forgo the economic benefits of deeper integration with China. A pragmatic approach that seeks to accommodate both powers is gaining sway.

GUNS AND BUTTER

Given that many developing countries are beginning to adopt ASEAN’s approach to managing competition between the United States and China, Washington would do well to learn from the association’s experience. The strategy ASEAN has used to balance the concerns and sensitivities of China and the United States (and other major powers such as India, Japan, and the European Union) could also enable the rest of the global South to do the same. China is already pursuing deeper trade and investment ties across the developing world. The United States must decide whether to deal pragmatically with these regions or continue with its zero-sum approach to competition with China and risk driving them away.

What would a more pragmatic U.S. approach look like? Consider three simple rules to follow when dealing with ASEAN and, by extension, the rest of the global South. The first is not to ask any country to choose between Beijing and Washington. There is a practical reason for this: compared with China, the United States has little to offer ASEAN. Strained finances and congressional resistance to expanding foreign aid mean that Washington has provided only a fraction of the assistance that Beijing has provided to the region. At the U.S.-ASEAN summit in May 2022, for instance, Biden pledged to spend $150 million on infrastructure, security, pandemic preparedness, and other efforts in ASEAN countries. Compare that with the $1.5 billion Xi pledged in November 2021 to help ASEAN countries fight COVID-19 and rebuild their economies over the next three years.

True, Washington has more to offer in terms of defense cooperation and arms sales. But relying too heavily on military rather than civilian cooperation could end up hurting the United States. As Paul Haenle, a China expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, remarked to The Financial Times, “The risk is that the optics in the region become the U.S. coming to the table with guns and ammunition and China dealing with the bread and butter issues of trade and economics.” It would be a huge mistake for Washington to be associated with guns while Beijing is associated with butter. The simple truth is that for most people in the global South, the first priority is economic development.

Any U.S. effort to counter Chinese influence in the global South is doomed to fail.

And for good reason. Having grown up in Singapore in the 1950s and 1960s, when the country’s per capita income was as low as Ghana’s, I understand how psychologically debilitating poverty can be. I also understand how psychologically uplifting it can be for the people of a poor country to experience development successes. Even as a child, I could feel the quality of my life improve as our family acquired a flush toilet, a refrigerator, and a black-and-white TV set.

This is why it has been a mistake for Washington to campaign against China’s BRI. Western governments and media have portrayed the BRI as a pernicious plan to ensnare countries in debt-trap diplomacy. But of the UN’s 193 member states, 140 have rejected that interpretation and signed agreements to join the BRI. The advantages many have reaped from doing so underscore the folly of asking countries to take sides.

The second rule is to avoid passing judgment on countries’ domestic political systems. ASEAN demonstrates why this rule is critical. The association’s ten member states include democracies, autocracies, communist regimes, and an absolute monarchy. In the rest of the developing world, the variety of regime types is even greater. For this reason, Biden’s decision to frame world politics as a struggle between democracies and autocracies is a mistake. In practice, Biden understands that the world is more complicated, which is why he traveled to the Middle East to meet with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in July 2022, despite having previously called Saudi Arabia a “pariah.”

The United States is only diminishing its own stature by calling on countries to shun China. Neither of the other two largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—see themselves engaged in an ideological struggle with Beijing, even if they have concerns about China’s rise. Nor do they feel that Beijing threatens their democracies. By carving the world up by regime type, Washington is just exposing its own double standards at the same time as many other countries are becoming more sophisticated and subtle in their political judgments.

Given the deep ideological conviction of many U.S. policymakers and opinion-makers that the United States should always be seen as a defender of democracy, it will be difficult for Washington to explicitly renounce this commitment. Yet the United States learned to work cooperatively with nondemocratic regimes (including communist China) during the Cold War. If it resuscitates that old culture of pragmatism, it can do so again today.

The third rule for engaging ASEAN and other developing regions is to be willing to work with any country on common global challenges such as climate change. Even if Washington is uncomfortable with Beijing’s growing global economic influence, it should embrace China’s rise as a leader in clean energy and renewable technologies. China is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases and the biggest user of coal today, but its investments in green technology will be crucial in fighting climate change. China leads the world in the production and consumption of renewable energy, manufacturing more solar panels, wind turbines, and electric car batteries than any other country. In short, there can be no feasible plan to fight climate change without involving China and its global economic partners.

Chinese investment will also be critical to ensure that other countries can fulfill their climate obligations while meeting their development and infrastructure needs. The Export-Import Bank of China has funded major solar and wind projects around the world, including Latin America’s largest solar plant, in Jujuy, Argentina, and a major wind farm in Coquimbo, Chile. China is also taking steps to make the BRI more climate-friendly, including by developing green-power, transportation, industry, and manufacturing projects. And it is expanding cooperation in green finance—for instance, by working with the EU to develop a common taxonomy for sustainable finance. Taken together, these efforts arguably exceed anything the Bretton Woods Institutions have done to combat climate change.

In short, U.S. policymakers should at least privately recognize that China’s growing economic influence can be an asset when it comes to solving shared global problems. In addition to climate change, poverty and pandemics could also be dealt with more effectively through greater cooperation between the United States and China. Such cooperation will remain elusive, however, unless Washington stops viewing any win for China as a loss for the United States and vice versa.

These three rules reflect an emerging reality to which Washington must adapt: developing countries are growing more sophisticated and better able to make autonomous decisions. The United States has done itself a big disfavor by framing the world in binary terms, as divided between good and evil, democracy and autocracy. If Washington can only work effectively with like-minded governments, it will be locked out of the global South, where most people have a different view of the world.

The vast majority of developing countries are clearly willing to work and cooperate with China. As a result, any U.S. effort to reduce or counter Chinese influence in the global South is doomed to fail. The United States should stop trying to cut China off from the rest of the world and start trying to identify areas where the two great powers can work together. As for the developing countries that wish to partner with both Beijing and Washington, the United States should look to ASEAN for guidance. Its pragmatic balancing act, or something like it, is the future for the rest of the developing world.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News