The once-vaunted unity of the V4 has been shattered by the war in Ukraine and Poland and Hungary’s diametrically opposed views on it. 2023 holds out little hope of a rapprochement.

Central Europe’s regional grouping of Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia was formed originally to coordinate positions before EU accession, and then served as a platform to find a common regional voice before EU summits.

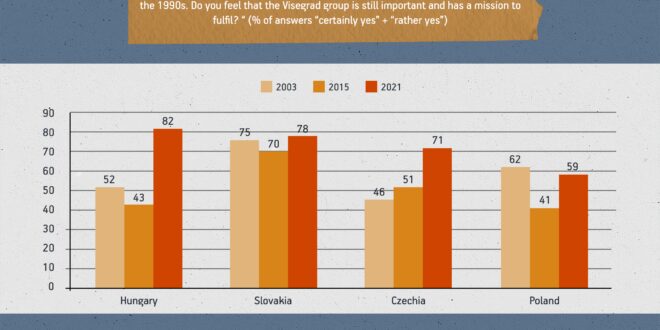

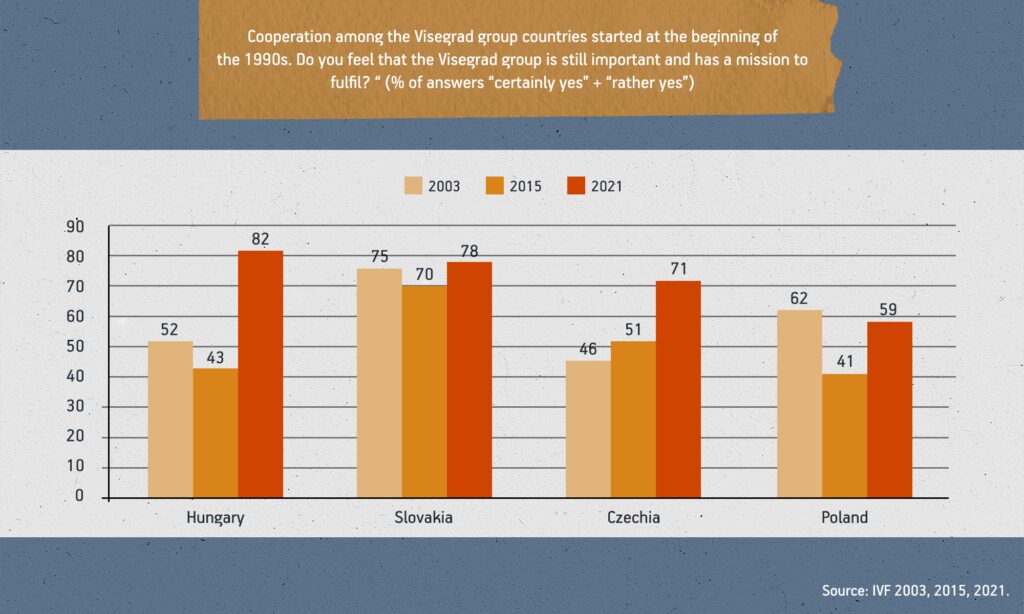

A 2021 survey of public opinion in all four Visegrad Group (V4) countries by the International Visegrad Fund found that support for and belief in the bloc was highest in Hungary, followed by Slovakia, Czechia and Poland. This was attributed to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban accentuating the V4 agenda as an important part of his European and overall foreign policy, which was inevitably accompanied by an increased volume of official communication.

The V4’s fortunes waxed and owned over its 30-year history, yet 2022 saw a crumbling of the hitherto close cooperation in the wake of the war in Ukraine, leaving the bloc facing perhaps its biggest existential challenge. Poland, a strong supporter of Ukraine in its fight against Russian aggression, has little time for Orban’s dissembling over the Putin regime, while the foreign policies of Czechia and Slovakia are back on Western trajectories.

A renaissance of the V4 format is not expected in 2023. Rather, the contrary is likelier, as Hungary remains isolated and the other three members continue to distance themselves from Orban on the international stage. The V4 will not be abolished, but cooperation will be relegated to lower-level contacts that focus mostly on economic and trade issues.

1.1 Overview

Although the V4 is a regional platform, its strength and ambitions depend largely on internal developments. Elections can be gamechangers.

2022 started with a changing of the guards in Czechia where Petr Fiala’s centre-right Democratic Bloc, a pro-EU coalition of five parties, took over from populist billionaire Andrej Babis. Czechia and Slovakia, holding the presidencies of the EU and Visegrad Group, respectively, in the second half of 2022, both exhibited fresh determination to cement their Western orientation.

This was not an entirely new phenomenon. For years, Bratislava and Prague have been trying to distance themselves from the “EU’s awkward squad” of Poland and Hungary, whose nationalist-populist governments were constantly squabbling with Brussels about issues such as the rule of law, press freedom and corruption.

As such, the regional alliance had been moving towards a bloc of V2+V2, although both the Prague and Bratislava governments made it clear they were keen to continue to cooperate with Budapest and Warsaw on issues of mutual interest.

But 2022 brought a fundamental shift inside the V4. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, relations between Hungary and Poland quickly chilled. The once-close allies are now worlds apart, which is inevitably having a devastating effect on V4 cooperation.

Orban, seen as the most pro-Russian politician in the whole of the EU, is no longer held in esteem by Poland’s ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party and its old guard. The Hungarian government hopes it is a momentary rift in bilateral relations, but experts believe the damage is more fundamental and will last for years.

Meanwhile, the Czechs and the Poles buried the hatchet over the controversial Turow coalmine in early 2022. “We’re done with negotiations, which were difficult and conflictual, but finished with success,” Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said in Prague in February. “This puts an end to the period of stagnation in the otherwise very good Polish-Czech relations. We are opening a new chapter today. This is what we, as neighbours, need.”

In the wake of the invasion, Czechia, Slovakia and Poland were quick to show solidarity with Kyiv, turning the V4 effectively into the V3 + Hungary. Continued threats from Orban to veto EU sanctions against Russia has further undermined any remaining unity in the bloc.

The first visible cracks in the V4 was the cancellation of the bloc’s defence minister meeting in Budapest in March. The meeting had to be called off by Hungary, then holding the V4 presidency, after both the Czech and Polish governments decided to stay away.

I have always supported the V4 and I am very sorry that cheap Russian oil is more important to Hungarian politicians than Ukrainian blood.

– Czech Defence Minister Jana Cernochova

Polish President Andrzej Duda also distanced himself at the time from Orban, while Polish Deputy Minister Wojciech Skurkiewicz told the Radio Information Agency in March 2022 that, “what is going on around the V4 gives no reason for optimism”.

Hungary tried to play down the significance of the diplomatic embarrassment and promised the meeting would be organized at a later data – which never happened.

Orban was also given the cold shoulder by Warsaw after his landslide electoral victory in April, meaning his first international visit was not to Warsaw as it had been in 2010, 2014 and 2018, but to Serbia, which is not even an EU member.

Some of the ice was broken when Hungary’s first female head of state (and loyal Fidesz member), Katalin Novak, visited Warsaw in mid-May with the mission of salvaging the special Hungarian-Polish relationship and keeping the V4 on life support.

Slovakia, which took over the one-year presidency of the V4 from Hungary in July 2022, found itself in a delicate position. Bratislava, the smallest country of the bloc and the only member of the EU’s inner core centred on the Eurozone, decided to play down foreign policy differences and concentrate rather on practical cooperation between the four.

Slovakia’s foreign minister, Ivan Korčok, said in mid-June: “It’s time to focus on specific projects that people in the Visegrad region will benefit from.”

While Orban often used the V4 as a support base for his fights with the EU and tried to build it up as an alternative power centre within the EU, the Slovak government opted for “a return to its roots”.

“Three presidents did not start the Visegrad cooperation in 1991 in order to make it a bulwark to protect Central Europe from the West and the EU,” Korcok wrote in an opinion piece. “They wanted the Visegrad Group to be a firm part thereof.”

Just like Orban, Korcok also stressed that the four countries do not necessarily agree on everything, whether it is Russia’s Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, the presence of US troops in the region, or support for Ukraine. “Insisting on the V4 acting as one political bloc within the EU is not a good idea,” he pointed out.

Bratislava set out common projects that the bloc could reunite around: fighting surging energy prices, reducing the region’s dependence on Russian energy, supporting more use of nuclear energy, continuing connecting the north and the south of Europe by road and rail, and working more closely on the V4’s joint approach to defence. The Czech government was quick to show support to the Slovak approach, but experts doubt the current rifts with Hungary can be healed in the short term.

“The significance of the Visegrad Group in regard to the war has declined,” Pavlína Janebova, an analyst with the Association for International Affairs, tells BIRN, arguing that relations within the group are at their worst since the 1990s.

In an interview with public broadcaster Czech Radio, Czech Minister for European Affairs Mikulas Bek said the group is “definitely not dead”, but that it is “taking a pause” because of Hungary’s position over the war. The group has had its ups and downs over the decades, but as long as it can find common policies or projects, it can survive, he added.

Zsolt Nemeth, chairman of the Hungarian parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee and one of the last remaining Atlanticists in Fidesz, argued to not let the war bury the excellent bilateral relations with Poland and predicted that despite ailing current relations, the two countries have a bright future together.

Yet this sounds like wishful thinking. After Slovakia took over the presidency of the V4, animosities with Hungary have continued to bubble. Another V4 meeting – this time, the speakers of the V4 parliaments – was cancelled in Bratislava in November, after the speaker of the Czech Chamber of Deputies, Marketa Pekarova Adamova, refused to sit down with her arch-conservative Hungarian colleague Laszlo Kover. “[The Hungarians] are Russia’s Trojan horse and I see it as important to send them a clear signal that this is unacceptable,” she was quoted as saying.

To avoid putting all cooperation on ice, a summit under the auspices of the Slovak V4 presidency was finally organised for November 24 and was attended by all four prime ministers in Bratislava. Fiala argued that: “The important thing is that we talk to each other. The V4 at the highest level has not met in recent months. It is certainly a useful format that has proved its worth in the past.”

Orban talked about “a success story of 30 years”, and tried to rally his colleagues around the topic that once cemented the bloc’s unity: the threat of illegal migration and the protection of the external EU borders.” Yet Orban, as is his way, could not resist his devilish side in the lead-up to the summit, when earlier in the week he was photographed wearing a football scarf depicting a map of Greater Hungary, which includes territories that today belong to neighbouring countries, at the farewell match of Hungary’s best-known player, Balazs Dzsudzsak. The photo went viral and inevitably prompted angry reactions from neighbouring governments, while Slovak Prime Minister Eduard Heger greeted Orban at the summit with a new scarf showing today’s borders.

1.2 Signals to watch in 2023

Early election in Slovakia: Following the successful motion of no-confidence against Eduard Heger’s minority government last December, early elections are scheduled for September. The outcome is highly unpredictable, but in the event the left-leaning populist Smer party gets back into power, either led by Robert Fico or in a coalition with Peter Pellegrini’s Hlas party, Hungarian Prime Minister Orban would regain an ally within the region and the EU. Experts say Orban would then try to work closely with Slovakia and re-establish bilateral cooperation so that a V2+V2 format would leave it less isolated. However, Slovakia, as the V4’s only Eurozone country, has a vested interest in the success of European integration, which would limit its openness to Orban’s techniques of undermining EU unity.

Poland election in November: The stakes in the Polish parliamentary election are high both for the EU and for the V4. If the right-wing PiS government is re-elected, the standoff with the EU will probably prevail and could force Morawieczki – or whoever succeeds him – to maintain a “marriage of convenience” with Orban in the rule-of-law disputes with Brussels. But the relationship will remain far from cozy as long as the Hungarian government maintains its current pro-Russian stance. A victory of the Polish opposition led by former European Council President Donald Tusk would be a blow for Orban and Hungary, and could cement divisions inside the bloc and bring cooperation close to a standstill.

With the war in Ukraine, the traditional Polish-Hungarian axis is broken, and until it is repaired, the V4 will be on survival mode and lack any dynamism.

– Daniel Bartha, president of the Centre for Euro-Atlantic Integration and Democracy

Economic and energy crisis: Decoupling from Russian energy is a challenge for most of the countries in the region. Regional cooperation could be strengthened by looking for common solutions to this. Poland could become a V4 hub for energy, being the only country with access to the sea and, as such, liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals. And nuclear energy is also an area where V4 cooperation could be strengthened. Yet Hungary seems determined to engage in short-termism by signing new oil and gas supply deals with Russia, deepening, not lessening, its reliance on Russian hydrocarbons

Migration flows: If migration picks up during 2023, whether through a deliberate weaponization of migrants by Putin or his ally Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko or continuing flows from the south, Orban will again try to rally the region around his anti-migration agenda. Populist forces in all countries will eagerly exploit such developments.

Alternatives emerging: Czechia and Slovakia are experimenting with the Slavkov cooperation with Austria. Having Austria on board is also a preference for Orban, who is boosting cooperation with Austria and Serbia to fight illegal immigration. The Three Seas Initiatives, a forum of 12 EU states, running along a north-south axis from the Baltic Sea to the Adriatic and Black Seas, could be a potential alternative to the V4, although historical and cultural ties are weaker in this format than in the V4.

1.3 An expert view

(Daniel Bartha, President, Centre for Euro-Atlantic Integration and Democracy, Budapest.)

2022 was one of the low points of the history of the V4. Will this trend continue in 2023?

The weakening of the V4 is a trend we have witnessed since 2019. Traditionally, it is the Hungarian rotating presidency which is the most ambitious of the four: this is not a coincidence, as the Hungarian V4 presidency overlaps with the parliamentary elections in Hungary, offering a stage for international meetings often used to demonstrate that the Orban government is not isolated. The Polish ambitions usually depend on their political leadership, but Prague and Bratislava have been distancing themselves from the other two for years, due to the ongoing spats with Brussels. With the war in Ukraine, the traditional Polish-Hungarian axis is broken, and until it is repaired, the V4 will be on survival mode and lack any dynamism.

Is there a threat it could fall apart?

No, I don’t think so – at least not until some other regional cooperation is able to take over its role. Czechia and Slovakia are experimenting with the Slavkov cooperation with Austria, but they demur with Vienna on nuclear energy. The Three Seas Initiative, which encompasses 12 EU members states, from the Baltics down to Bulgaria and Croatia, also including Austria and the V4, could become a platform for some infrastructure investments, but it is too broad based to coordinate political approaches.

Where can you see any potential for V4 cooperation in 2023 in spite of the political differences?

I think energy, especially nuclear energy, is an area where the V4 countries could look to find common solutions. They all need a partner not just to supply them with fuel rods but also to take care of the highly radioactive used fuel elements. This was part of the nuclear deal with [Russia’s] Rosatom, but the US company Westinghouse, one possible alternative to the Russian company, is not keen to take in used nuclear fuel; actually, it is currently only Russia that is offering this service. The V4 could come up with a joint solution.

Orban tried to raise migration as a central threat and rally his colleagues around this topic at the last V4 summit. Could migration become a focal point for the V4 again?

If migratory pressure grows, which cannot be ruled out due to grain shortages in a number of poor countries, populists will again play the immigration card. This could happen in Slovakia during the election campaign. But I do not think it would be a gamechanger in Czechia or in Poland. Ultimately, Orban is also aware of this and rather discusses the issue with Austria and Serbia, where migration is a more pressing issue.

Can the V4 remain a format for coordination inside the EU?

There are still common interests of the V4 inside the EU, so coordination will probably prevail in those areas. EU enlargement and the development of the Western Balkans are surely two of those, but there are also shared interests in finding a viable solutions in energy transition, industrial politics and cohesion funds. But ultimately a lot will depend on the two elections in the V4 in 2023: if Fico or Pellegrini return to government in Bratislava and PiS remains in power in Warsaw, there are chances of a strengthened V4 cooperation inside the EU. If they land on the opposition banks, it will be a grim year for the V4.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News