In 2020–2022, Tunisian illegal migrants traveled through Serbia to reach Western Europe, as an alternative to the hazardous, more monitored Mediterranean route. This was driven by push factors in Tunisia, including deteriorating economic conditions and government acquiescence, and pull factors in Europe, namely smuggling networks and Serbian authorities looking the other way. While the route was sealed for Tunisians in November 2022, as long as transit states can use illegal migration to secure geopolitical leverage, such actions will continue.

KEY THEMES

- The deterioration of economic conditions in Tunisia following the COVID-19 pandemic and President Kais Saied’s effective coup of July 2021, which isolated the country from international donors and investors, helped drive illegal migration.

- The Serbia route provided a safer, less monitored passage to Western Europe than the Mediterranean route.

- Migrants from the marginalized region of Tataouine favored the Serbia passage especially and were helped financially by a regional diaspora living in Europe.

- The Tunisian state also welcomed the Serbia route. More migrants ensured higher remittances, while the government maintained deniability because Tunisians at the time required no visas for Serbia and Türkiye.

- Among the pull factors in Europe were smuggling networks, many from North Africa, who organized passage from Serbia to Hungary and beyond.

- Serbia’s ambivalence toward illegal migration was another pull factor. Serbia used migrants as political leverage, until termination of the visa-free regime closed the route to Tunisians.

FINDINGS/RECOMMENDATIONS

Smuggling networks in Serbia, divided by ethnic affiliation, were highly adaptable, allowing them to satisfy the sudden increase in demand for their services in 2021 and 2022.

Competition among smuggling networks produced a rationalization of migrant flows using social media platforms, financial transfer procedures, and systems of transportation and accommodation.

In allowing migrants to cross its territory, Serbia secured advantage over the EU in a context of vanishing hopes of accession to the union, border disputes with Kosovo, and pressure to align with EU sanctions against Russia.

Though the route was closed to Tunisians in November 2022, Serbian actions sent a message to the EU that only Serbia’s accession would decisively resolve the migrant issue.

Transit countries will continue to look the other way on illegal migration if it helps them to achieve political, financial, or geopolitical aims that are otherwise difficult to secure.

The EU needs to offer a strategic horizon to countries in its neighborhood, one based on shared prosperity aimed at reducing illegal migration. Without an effective common system for dealing with illegal migrants, the EU will remain vulnerable to pressure.

INTRODUCTION

Between 2020 and 2022, illegal Tunisian migration to Western Europe through Serbia rose dramatically as migrants sought routes different than the seaborne passage across the Mediterranean. While European Union (EU) pressure forced Serbia to close down the so-called West Balkans route to Tunisians in November 2022, its implications remain relevant today, as some states might have a broader national interest in adopting similar actions down the road, even as the nonstate actors involved continue to have a stake in sustaining the route.

The Serbian route, which was used by Tunisians and migrants from other nationalities, many from North Africa, showed that in an interconnected world, illegal migration has become an unconventional weapon used to build political leverage, extract resources, and gain influence over stronger and wealthier countries. States to the EU’s south and east are aware of the extent to which mass illegal immigration can cause tensions and polarization within the union, and have at times used this to push the EU to make concessions.

As the EU has sought to control illegal immigration, particularly from North Africa, it has had to address several levels of challenges. Not only has it faced strong push factors in the countries of origin, it has also had to wrestle with pull factors within Europe—the foreign policy agendas and interests of non-EU transit countries, not to mention the mercenary objectives of illegal migrant smuggling networks and others. This was shown most notably in 2015, when Türkiye allowed migrants and asylum seekers to sail to Europe in order to pressure the EU into accepting a $6 billion deal to help Ankara keep the refugees. In addition to the financial deal concluded in 2016, the European Union agreed to reduce visa restrictions for Turkish citizens, update the customs union, and reactivate stalled discussions regarding Türkiye’s accession to the European Union.1 More recently, Belarus created a migrant crisis in 2021 by easing entry procedures for Middle Eastern migrants, then facilitating their passage to the borders it shared with EU member states.2 This was a response to EU sanctions that had been imposed on Minsk.

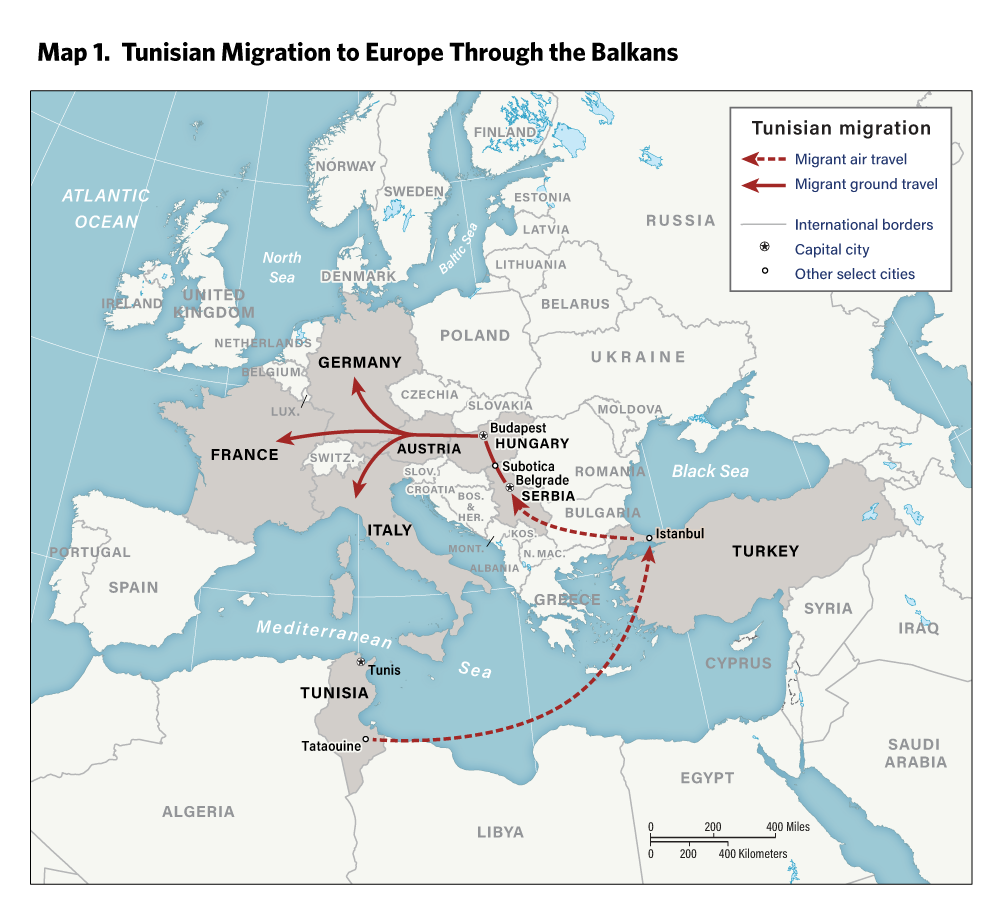

While Serbia did not create crises of the same magnitude as Türkiye and Belarus, it did view illegal migration as an instrument in its own complicated relationship with the EU. Rising flows of migrants and heightened controls along the maritime route across the Mediterranean pushed transnational smuggling networks to look for less risky, though longer and more expensive, alternatives. Benefiting from the fact that Tunisians could travel to Türkiye and Serbia without visas, illegal migrants relied on North African smuggling networks to help them cross the Serbian-Hungarian border on their way to Austria and the rest of Western Europe.

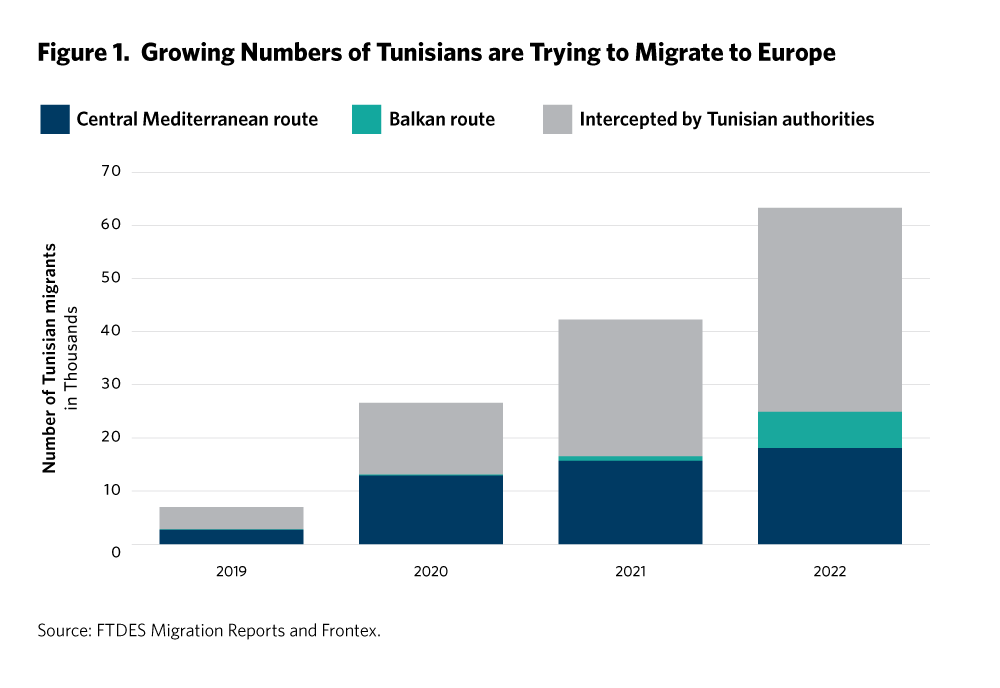

The number of illegal Tunisian migrants detected on the West Balkans route dramatically increased from 190 migrants in 2020 to 842 in 2021 and 6,782 in 2022.3 This route was taken especially by thousands of young people from Tataouine, a marginalized Tunisian region located near the Libyan border. This reflected a wider trend.4 According to Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, 145,600 undocumented migrants took the Serbia route in 2022, 136 percent more than in 2021.5 This was the highest number reported on this route since 2015, representing about half of all reported illegal entries into the EU in 2022.6

The Serbia route illustrated the dynamics of manipulating migration flows in times of globalization and populism. It was a consequence of converging interests among state and nonstate actors as well as legal and illegal entities, involving the Serbian and Tunisian states and agile migrant smuggling networks. All of them took advantage of the initial absence of a coordinated response by European countries to exploit weak spots in pursuit of their financial, social, or geopolitical goals.7 This is a reality the EU will have to continue to take into consideration. It suggests that merely trying to deal with the push factors of illegal migration in countries of origin may not be enough, as the pull factors in states surrounding the EU are likely to remain substantial, even if these will vary from state to state, depending on circumstances.

THE FACTORS PUSHING MIGRATION IN TUNISIA

From mid-2020, the Serbian route emerged as an alternative passage for Tunisians fleeing a deteriorating economic situation and political stalemate at home. In the context of tightening controls in the Mediterranean, the West Balkans route represented a way out for thousands of young people and their families, one that posed less risk than the maritime crossing, while offering the Tunisian state deniability vis-a-vis its international partners.

Tunisia was hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, which came after a decade of low growth, leading to an acceleration of migration flows.8 In 2020, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) declined by 9 percent, more than 200,000 Tunisians lost their jobs,9 thousands of small and medium-sized enterprises closed down,10 and the percentage of the population living below the poverty line rose from 15 to 21 percent.11 In July 2021, Tunisian President Kais Saied organized a power grab, suspending parliament, dismissing the prime minister, and securing judicial powers, which had the effect of exacerbating political deadlock in the country and intensifying Tunisia’s isolation from donors, investors, and international partners.12 For tens of thousands of Tunisians, particularly those from disadvantaged areas, migration was the only option left. A national survey conducted that year showed that 40 percent of Tunisians between the ages of fifteen and twenty-nine said they wanted to leave the country.13

This sentiment was hardly new. Waves of illegal migration began during the early 1990s, reaching a peak in 2011, following the fall of then president Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. That year, 28,800 Tunisians exploited the collapse of Tunisian border controls and crossed the Mediterranean.14 For half a decade flows of migrants from Tunisia, including non-Tunisians transiting through the country, remained remarkably constant, with an annual average of 2,500 arrivals in Europe, before the numbers began rising slowly in 2017.15 In early 2020, they increased sharply, even as Tunisia and Italy reinforced maritime border controls. That year, 12,900 Tunisian migrants arrived illegally in Italy whereas 13,500 others were intercepted.16 The surge accelerated in 2021, with 15,700 Tunisians arriving in Italy and another 25,700 migrants prevented from doing so.17 In 2022, illegal migration from Tunisia continued to rise, with 18,100 arrivals in Italy, and 38,400 people prevented from completing the crossing, which indicated the success of tighter border control measures.18

The misfortunes of Tataouine, a major source of illegal Tunisian migration, is a good illustration of the dynamics at play. The economic decline there in recent years and the dashed hopes of what is known as the Kamour protest movement, which shook the region for months in 2017, and again in 2020, encouraged departures.19 Paradoxically, Tataouine has hydrocarbon resources, and its oil and natural gas fields contribute 20 percent of Tunisia’s natural gas output and 40 percent of its oil output.20 Despite this, the region has remained severely underdeveloped, with above-average unemployment and a stunted private sector. In 2021, Tataouine’s unemployment rate was the highest in the country at 32.5 percent, compared with the national average of 15.3 percent.21 The percentage of unemployed graduates in Tataouine is also one of the highest nationwide, estimated at 58 percent in 2019.22 Historically the region’s population has migrated to France, which counts a large diaspora of people from southern Tunisia.23 In addition, before 2011 Libya represented an attractive labor market for young people from the region, but the conflict there brought this to an end.24

The rising disenchantment that fueled migration from Tataouine needs to be understood in light of three factors that created a systemic crisis in the region. The first is Libya’s decline as an economic lifeline for the region. The waning of the cross-border economy, with the concomitant loss of thousands of jobs and vital incomes, as well as the absence of employment prospects because of the Libyan conflict, aggravated the profound problems already affecting Tataouine.25 The second is the increasing militarization of the border region. This not only harmed the border economy, but also limited grazing areas, aggravating the crisis of pastoralism, which had already been strongly affected by drought and climate change. The local animal herding economy has also been hurt by surging prices and the ensuing shortages in animal feed.26 The third is the disenchantment caused by the failure of the Kamour protest movement, which had demanded that the state implement initiatives to create jobs and develop Tataouine economically.27 While protesters won concessions from the authorities through a June 2020 agreement that recognized many of their demands, since Saied’s seizure of power the state has failed to fulfill its promises, generating more discontent.28

As a result, thousands of young people from the southern border areas migrated, or tried to migrate, to Europe starting in 2020.29 The Serbia route was particularly attractive for two main reasons. It was safer than the maritime route, where the likelihood of being caught by the authorities was also high; and migrants were able to rely on the support of a southern Tunisian diaspora based mainly in France that funded their journeys through money transfers, making the longer West Balkans route more affordable. While there are no figures available for the number of migrants, observers from Tataouine have estimated that thousands of people from the region took this route in 2022.30 Southeastern Tunisians make up 12.7 percent of the Tunisian diaspora, while over 7 percent of the population of the southeast lives in the diaspora.31

The Tunisian state was a main beneficiary of the Serbia route, which offered it several major advantages. First, it gave thousands of dissatisfied youths an exit route at a time when the central Mediterranean passage had become more difficult due to tighter security. These migrants’ remittances represent a source of much-needed hard currency for Tunisia. In the decade between 2011 and 2021, remittances in foreign currencies were higher than both tourism revenues and foreign direct investment, making them one of the major sources of hard currency for the country.32 Moreover, the trend was on the rise during that period. In 2021, remittances were 28 percent higher than in 2020, accounting for 4.7 percent of Tunisia’s GDP.33 In 2022, they exceeded 9 billion dinars ($3 billion), which was 13.5 percent higher than in 2021.34

In light of the Tunisian state’s reliance on remittances, and amid growing pressure from Italy and the EU to curb illegal migration by sea, the Serbian route provided Tunis with plausible deniability for the waves for migrants heading toward Europe. The reason for this is that there were no visa restrictions for Tunisians traveling to Serbia and Türkiye. Tunisia saw no advantages in limiting their travel to these countries, and paid no price for allowing them to do so. However, soon after Saied’s effective coup of July 2021, it was clear to the main Tunisian political actors that migration would be a fundamental factor in determining the international community’s attitude toward the president’s regime. Indeed, the last speaker of parliament before Saied suspended the legislature, Rached Ghannouchi, warned that in the absence of a restoration of democracy, “over 500,000 Tunisian migrants could try to reach the Italian coast in a very short time.”35 The defensiveness of Saied’s response showed his sensitivity on the question. He declared that the opposition was paying Tunisians to embark for Europe, thereby damaging Tunisia’s interests and relations with European countries.36

The Tunisian migration wave caused concern in the EU.37 Between 2018 and 2021, over a third of the illegal migrants reaching Italy by sea were Tunisian.38 More importantly, of the more than 25,000 people of all nationalities who were held in Italian detention centers in 2020, almost half were Tunisian.39 With the intensification of migration flows, European demands increased on Tunis to control its borders and implement fast-track procedures to repatriate illegal migrants. Italy and Tunisia concluded a migration agreement on August 17, 2020, after a visit by Italy’s foreign and interior ministers to Tunis.40 The details of the accord were never made public. According to a document published by Italian investigative journalists, however, the migration deal included multimillion-euro funding for Tunisia in exchange for a commitment to repatriate its illegal migrants.41 This financial deal allegedly included €8 million (approximately $9.1 million) for Tunisia’s Coast Guard and the creation of a €30 million (about $34 million) fund over a three-year period (2021–2023) to help Tunisia combat illegal migration.42

Despite popular discontent and civil society criticism of the lack of transparency over the deal, the Tunisian authorities remained silent. In a context of harsh social and economic crises and the increased isolation of Saied’s regime from international donors and investors, this reflected the president’s desire to use migration agreements to secure the support of international partners, or at least ease their opposition to his regime’s erosion of democracy.43

Saied certainly did reinforce the presence of the Navy and Coast Guard along Tunisia’s maritime border. The result was that six times more illegal migrants were intercepted at sea in 2021 than in 2018.44 The cooperation in stemming migration flows also led to an acceleration of readmission processes. In 2020, 1,922 Tunisians were returned from Italy, representing 73.5 percent of the total number of returnees from all nationalities, far greater than the number of Egyptians and Albanians.45 The total number of Tunisian illegal migrants who were deported was 1,872 in 202146 and 1,700 by October 2022.47

The Serbia route also offered a third advantage in that it provided a social safety valve for the Tunisian authorities and oil companies operating in Tataouine. The failure of the government and the companies to implement the promises made to the Kamour movement could have provoked new protests, so both were relieved by the departure of youths who might have led such a movement. This could have blocked oil production once again, as it had done in 2020, especially in the midst of the energy crisis caused by the war in Ukraine.48 As migration emptied the region of its young men, observers concluded that this reduced the likelihood of a new protest movement emerging anytime soon.49 In parallel to the departure of thousands of rebellious youths, in 2022 many leaders and organizers of the Kamour protests were convicted before military courts and jailed for actions dating back to the events of 2017 and 2020.50

Migration in Tunisia has always served to compensate for the failure of those in power to fulfill the expectations of youths and respond to their demands. This is especially true of youths who come from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. A report published in March 2022 by a group of nongovernmental organizations, based on a sample of migrants deported from Italy, revealed that Tunisian migrants were mainly males from underprivileged backgrounds who had limited professional qualifications.51 Of the returnees, 75 percent were between the ages of twenty and thirty and had only primary or secondary levels of education, and 50.9 percent were unemployed. Half of them had no income, while 11 percent earned 200–400 dinars ($70–$120) per month, and 19 percent earned 400–600 dinars ($120–$200) per month. Of those who made the crossing, 26 percent managed to reach Italy after multiple attempts.52

In light of this situation, the Serbia route took on considerable importance as the push factors driving illegal migration in Tunisia hit up against rising EU efforts to limit the migration flow. However, it was not Tunisia and Tunisians alone who saw advantages in exploiting the Serbian route, as the pull factors across the Mediterranean were also highly significant.

THE PULL FACTORS FOR ILLEGAL MIGRATION THROUGH SERBIA

There were numerous pull factors in Europe that led state and nonstate actors to exploit the passage through Serbia. The allure of the Balkans route emerged as a result of the willingness of the Serbian state to take advantage of the migration flows, partially to advance its own political objectives with respect to the EU. It also played into the interests of certain security institutions in Serbia, not to mention the corrupt practices of some of their members. Such dynamics created a space for agile smuggling networks to thrive.

SMUGGLING NETWORKS: PROFITABLE AND ADAPTABLE

At the heart of illegal migration operations through Serbia were networks of smugglers from North Africa. In 2015, the massive influx of refugees to Europe greatly destabilized the EU. The decision of Macedonia to seal its border with Greece in February 2016 and the EU-Türkiye deal of March 20 the same year considerably reduced the stream of people through the Balkans.53 However, the measures adopted to crack down on illegal migration led to a mushrooming of smuggling groups in the region.54 By increasing the dangers faced by migrants—detention, assaults, arrests, deportations, and a recourse to more dangerous and longer migration routes—the measures only made smuggling networks more indispensable.55 These networks, in turn, took advantage of procedures or security vacuums in Europe that allowed them to organize the movement of migrants across borders on the Balkans route.

Smuggling networks organized themselves according to ethnic affiliation. There were North African, or Maghrebi, networks, as well as Syrian, Afghan, and Turkish networks. Starting in mid-2020, North African migrant smugglers placed themselves on the Serbian-Hungarian border and activated their connections in Türkiye and North Africa to contact, convey, transport, and secure border crossings toward Western Europe.56 These networks were usually labelled according to the nicknames of their leaders, often derived from their cities of origin, such as “Al-Kazaoui,” for a smuggler from Casablanca in Morocco, or “Al-Tetwani,” for another Moroccan smuggler, from Tetwan. The proliferation of networks along ethnic or national lines underlined that the smuggling market in the Balkans was not monopolized by any single organization.

This expansion of smuggling networks allowed them to satisfy the sudden increase in demand for their services in 2021 and 2022. Competition between the networks produced a sort of rationalization of migrant flows using social media platforms, financial transfer procedures, and systems of transportation and accommodation. Social media platforms matched migrants with smugglers and helped manufacture these population flows.57 The Maghrebi networks were well organized, with transporters conveying migrants in Serbia to Hungary and Austria and others responsible for organizing crossings on the Serbian-Hungarian border.58

These networks’ use of social media, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Signal, to attract potential migrants showed their level of sophistication.59 Facebook pages were updated daily (and later deleted) with photos and videos of the border crossings, as well as lists of names of migrants who had succeeded in arriving safely at their final destinations in Western Europe. The pages portrayed a migration market in which smuggling networks competed to offer the best services and gain the approval of future migrants or clients. Networks were usually selected by virtue of their trustworthiness, reliability, and respect for their charges, and social media platforms were essential in shaping public views on all these issues.60 Migrants also recorded or live-streamed their journeys, offering recommendations to future migrants. Rumors about new migration routes, potential transit countries, difficulties, or restrictions often spread very rapidly, showing the litheness and adaptability of these networks.

Tunisian migrants tended to negotiate package deals with smugglers, which they referred to as “delivery” (taslima) operations.61 These deals allowed them to secure the smugglers’ services to cross Hungary and reach Austria, whereas those who had paid less would have had to cross Hungary on their own.62 This required a high degree of planning and the mobilization of transnational networks as smugglers constantly had to change their itineraries and the methods used to move migrants. Migrants were transported inside Serbia to the border with Hungary and placed in settlements near the Hungarian border. There they were accommodated in abandoned farmhouses and factories, before being smuggled into Hungary and then on to Austria.63 Sometimes, the destinations could be even deeper inside Western Europe.

For Tunisians, a single journey between Serbia and Western Europe cost €4,000–€7,500 (around $4,300–$8,100), without taking into consideration the expense of traveling to Türkiye and from Türkiye to Serbia, because no direct flights exist between Tunisia and Serbia.64 The Tunisian diaspora played a vital role in financing these journeys because of currency restrictions in Tunisia. The Tunisian government does not allow travelers to carry more than 6,000 dinars (about €1,800) with them annually, so migrants had to mobilize their family connections to find alternative ways of paying smugglers. Many turned to relatives in Western Europe for euros, in return for which they were reimbursed in Tunisian dinars.65 The relatives transferred the money to Serbia using money transfer operators such as Western Union.66 These channels showed that flexible financial arrangements were in place to support the sudden expansion of migrant demand following the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, the revenues of smuggling networks along the West Balkans migrant route (starting in Türkiye and including Serbia and Hungary) was worth at least €50 million ($54 million) in 2020.67 The revenues of smuggling networks in the border areas between Serbia and Hungary, in turn, ranged from €8.5 million to €10.5 million in 2020 (equivalent to around $9.7 million to $11.9 million that year).68

THE EQUIVOCATION OF THE SERBIAN STATE TOWARD ILLEGAL MIGRATION

The ambivalent attitude of the Serbian authorities toward migration and smuggling networks operating within their borders played an important role in the revival of the West Balkans corridor after 2015 and its attractiveness to Tunisians, and North Africans more generally.

The reopening of this corridor took place in a context of distrust between the EU and Serbia. The EU suspected, without openly accusing, the Serbian authorities of playing a double game.69 On the one hand, Belgrade reiterated its commitment to bringing Serbia into the EU, on the other the EU sensed that Serbia was indirectly helping Russia by fueling dissension within the EU through an influx of migrants—a tactic that Russia’s allies, such as Belarus, had used before along the EU’s borders.70 Without weaponizing migrants as Belarus did in 2021, Serbia subtly manipulated the migration card. In allowing migrants to cross Serbian territory, it saw an opportunity to secure relative advantage over the EU in a context of vanishing hopes of accession to the union, border disputes with Kosovo, and pressure to align with EU sanctions against Russia.71 Enlargement fatigue in the EU reduced Serbia’s incentive to conform with EU conditions on foreign policy, migration regulation, and even democratic governance.72

The disagreements between Serbia and the EU seemed to be profoundly affected by the lack of progress in the accession negotiations, which began in 2014.73 Divergences over sanctions imposed on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 reinforced tensions. Though Belgrade supported United Nations General Assembly resolutions condemning the invasion, it refused to suspend Air Serbia flights to and from Moscow.74 As in 2014, after Russia invaded Crimea, Belgrade was reluctant to align with the EU in imposing trade and financial sanctions on Russia.75 It also rejected cutting imports of Russian natural gas, a goal outlined by the European Commission.76 Serbia even signed a new gas supply deal with Moscow in May 2022.77

These strains affected Serbia’s position regarding illegal migration. Frontex detected 145,600 illegal crossings in 2022,78 the highest number of illegal crossings reported on the Serbian route since the crisis of 2015, and about half of all reported illegal entries into the EU in 2022.79 These migration flows, along with the arrival of migrants from nationalities that hadn’t previously taken the route in such numbers, threatened EU member states with a major influx through the West Balkans, after they thought the problem had been resolved in 2016.

The manipulation of migration flows was also made possible thanks to the complicity between the smuggling networks and elements of the Serbian police, probably with the tolerance of the Security Intelligence Agency, which is led by a pro-Russian official.80 This offered deniability to the Serbian authorities, especially as Serbia has a reputation of collusion between the security services and organized crime.81 The smuggling networks had corrupt police officers on their payrolls as a safeguard against law enforcement operations, but also to help them compete with rival networks.82 At the Serbian-Hungarian border, an economy of protection flourished as the migration market expanded. Larger smuggling groups intimidated or used violence against smaller ones, as well as against migrants not employing their “services.” Often, this ended in armed confrontations. For example, on July 2, 2022, a clash took place between two smuggling groups in the town of Subotica on the border with Hungary.83

Serbia’s accession process to the EU was supposed to roll back the power of organized crime networks and their links to the state. However, this hasn’t happened. On the contrary, those ties have become stronger under the current Serbian Progressive Party of President Aleksandar Vučić.84 These relations have been criticized openly by the EU as a vital element undermining governance in Serbia, which has hindered the country’s entry into the EU.85 Since then, things have changed for the worse. Serbia has been downgraded from a “free” country to one that is “partly free,” characterized by widespread corruption as well as pressure on the country’s political opposition, independent media, and civil society.86 Such an environment, marked by opacity, a lack of accountability, and the coercion of civil society and media outlets, only makes it easier for state agencies to manipulate illegal migration.

Belgrade’s ambivalence toward regulating illegal migration to the EU sent a more general message that countries on the union’s periphery might opt to do the same thing. Countries that play this card are described as “stabilitocracies.”87 A “stabilitocracy” has the capacity to use supposed stability as a bargaining chip to secure external legitimacy and advance strategic goals, despite its own shortcomings in terms of democracy and human rights. States in the EU’s neighborhood, such as Türkiye, Serbia, Morocco, and Macedonia have used stability to receive Western economic assistance and political support in exchange for helping resolve regional problems, such as controlling refugee and migrant flows. Serbia’s strategy was driven more by a desire to seize the geopolitical moment and remind EU capitals that are skeptical about enlargement—notably Paris and The Hague—that they were wrong in believing they could indefinitely keep Balkan countries on hold in the EU enlargement process.88

THE END OF THE SERBIA CORRIDOR?

The rising tensions between Serbia and the EU led Brussels to accuse Belgrade of a lack of cooperation and an unwillingness to harmonize its visa procedures with those of the EU. Officials from the EU viewed Serbia’s visa-free regimes with countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East—including Burundi, Egypt, India, Morocco, and Tunisia—as the problem.89 In October 2022, the EU commissioner for home affairs threatened to halt Serbia’s visa-waiver access to the Schengen bloc if it did not end illegal migration through its territory.90

This had an immediate effect when, in late October 2022, around sixty Tunisian migrants who had landed in Belgrade from Türkiye were obliged to return to Istanbul.91 Less than a month later, on November 20, Belgrade imposed visa requirements on citizens from Tunisia and Burundi, signaling the apparent end to mass migration from Tunisia via the Serbian route. While Serbia ultimately bowed to EU pressure, its actions managed to send a message to the EU that only Serbia’s accession would decisively resolve the migrant issue, until which time uncertainty would remain on this front. Indeed, to become an EU member state, Serbia must align its visa policy with that of the EU countries. This means that sooner or later Serbia will have to introduce visa procedures not only for Tunisian citizens but also those of other countries who do not require visas to the Schengen area. Therefore, the illegal migrants transiting through Serbia were partly useful in pressing the EU on an acceleration of the enlargement process. This was all the more effective in a context where the EU’s capacities to absorb refugees and migrants were overstretched due to the wave of refugees from Ukraine. Around 5 million Ukrainian refugees have been registered for national protection schemes in Europe since Russia’s invasion of their country in February 2022.92

In the months following the restrictions, it was unclear how the smuggling networks would adapt to the new situation and whether the measures would stem the flow of migrants from other nationalities as well. However, the EU-Türkiye deal in 2016 suggests that while the number of illegal migrants may be reduced, the new situation will compel smuggling networks to adjust to transporting lower numbers of migrants. The sealing of the borders after the agreement with Türkiye also showed how small smuggling networks resorted to petty crimes to replace lost income, while the more sophisticated networks looked for alternative routes to continue smuggling migrants, which required higher levels of corruption.93

It’s also very likely that longer, more dangerous, and more expensive routes will be tried by North African smugglers and illegal Tunisian migrants to bypass restrictions. Indeed, some migrants have already tried to cross into Serbia from Bulgaria, risking arrest, deportation, or worse in the forests between the two countries. Moreover, if migrants from Tunisia and Burundi are ever prevented from entering Serbia, those from other countries could still take this route or find new itineraries. That is the case of Cubans, for example, who began exploiting visa-free travel to Russia and Serbia in order to enter the Balkan migration route to the EU.94

Since 2015, EU member states have been focused mainly on “extinguishing fires” when it comes to migration issues—dealing with crises by closing routes and striking deals. The EU-Türkiye agreement in 2016 and the threats that forced Serbia to close the West Balkans route were temporary measures meant to buy time. In fact, the EU sought to replicate the strategy it had adopted with Türkiye by implementing it elsewhere. It would externalize the solution to illegal migration by ensuring that the governments of transit countries would compel migrants and refugees to stay in place. The EU signed agreements with Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Senegal along these lines.95 Much the same thing was done on the central Mediterranean maritime route as well. After a wave of illegal migration from Libya between 2014 and 2019, Italy agreed to fund militia-run detention centers inside Libya, where thousands of African migrants who were trying to cross into Europe were held.96

However, such arrangements are only effective for as long as there is an alignment of interests between the EU and these countries. What is certain along potential migration routes into EU member states is that the transit countries may continue to look the other way on illegal migration if it helps them to achieve political, financial, or geopolitical aims that would otherwise be difficult to secure.97 Whether it is Türkiye, Belarus, Serbia, or weaker countries such as Tunisia or Libya, all understand this reality. That is why the EU needs to offer a broader strategic horizon to these countries. Among the ideas that can be explored are job creation measures in Europe’s southern and eastern neighborhood, such as the establishment by European companies of manufacturing facilities in nearby countries that are prone to migration, rather than in East Asia. The rationale here is that shared prosperity will reduce migration. Another is expanding legal migration through temporary working permits in certain sectors, which could allow circular migration, where workers rotate between home and host countries. A third is forming strategic partnerships that facilitate economic integration, again to stabilize countries to the EU’s east and south through heightened prosperity. However, these measures only target push factors, without addressing pull factors in Europe. At a time when Europe is divided over crucial issues related to the enlargement process, manipulating migration is likely to remain a wild card that many countries will be tempted to use again.

CONCLUSION

The visa requirement to Serbia created a serious challenge for Tunisians. In addition to the food and energy shocks caused by the war in Ukraine, the lack of rainfall has seriously impacted agriculture, raising food prices and threatening rural populations. This will inevitably push younger Tunisians to continue to make their way to Europe. Despite economic hardship, it was noticeable that protest movements in Tunisia were limited in 2022. This reflected the political fatigue prevailing in the country, as well as the resignation of a large part of the population. Such factors explain why migration will remain a reality in the foreseeable future.

Meanwhile, European states are anticipating that illegal migration to Europe will continue to rise in 2023.98 In 2022, migration was driven by the consequences of the Ukraine war. This is bound to continue in 2023 as prices rise across the board, particularly food and energy prices. The magnitude of illegal migration in 2023 will depend on the ingenuity of smuggling networks in adapting to new restrictions, seizing opportunities, and finding new routes. In the long run, absent an effective common system for dealing with illegal migration, the EU will remain vulnerable to exploitation and pressure. Due to the lack of common procedures for administering migration movements within the union and an ineffective system of sharing responsibility for asylum seekers, the EU will continue to go through crises every time it experiences a major influx of illegal migrants.

Tunisia’s example illustrates the flexibility of transnational movements of people in today’s interconnected world. The way nonstate actors operate can be adjusted quickly, as can the strategies of the various states involved in migration flows. The example of Serbia tells us a great deal about migration regulation, geopolitics, and the relations of state and nonstate actors in exploiting illegal migration. The fact that the EU managed to close the Serbia route for now does not necessarily imply that similar practices won’t continue elsewhere. The motives that many states on Europe’s periphery have to allow this will remain present in the future.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News