On Monday, Hungary’s legislature approved Finland’s accession to NATO, 265 days after Helsinki signed the protocols to join. The vote moves the long-delayed process forward, but it still leaves unaddressed both when exactly Hungary will take up Sweden’s accession and why the Hungarian government has taken so long. After all, it took the first twenty-eight NATO members fewer than ninety days to ratify both Finland and Sweden’s accession. Hungary and Turkey have been the holdouts, and while they have shared this status, it is important to look at the differences in how Budapest and Ankara have handled the process. Doing so raises new concerns about Hungary’s approach to the Alliance beyond the specific issue of this enlargement.

The reasons Turkey has taken longer are well documented. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been quite clear on his major interests related to arms exports and in particular to Stockholm’s attitude toward Kurdish groups with alleged links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union (EU). And Turkey’s lengthy process toward ratification has strained Alliance cohesion and made happy its enemies, such as Russian President Vladimir Putin. That’s not a small deal.

Still, Turkey early on presented detailed arguments and conditions that allies could debate and sort out. In contrast, Budapest has been opaque on the reasons why it delayed ratification on Finland and continues to do so for Sweden. Given that other allies delivered more than six months ago, lack of time has long ceased to be an acceptable excuse.

The biggest concern with Hungary now is less that it might keep Sweden in limbo for a few more months before ratification, and more that it might do so without plausible arguments. Leaving no room for a meaningful discussion, Budapest impedes the basis on which the Alliance deals with critical issues and inhibits the bedrock foundation of democratic life itself: open and purposeful debate.

Lack of time?

For months, Budapest has signaled that the ratification of Sweden and Finland was merely a matter of finding a time slot for lawmakers to vote. After the Nordic pair signed accession protocols in July, a few other NATO members—where the enlargement agreement is a more complex process and goes through their national assemblies—struggled to find time for a few months last spring and summer, as parliamentarians were heading for summer recess. Some convened extra sessions to advance the ratification, while Hungarians continued postponing it.

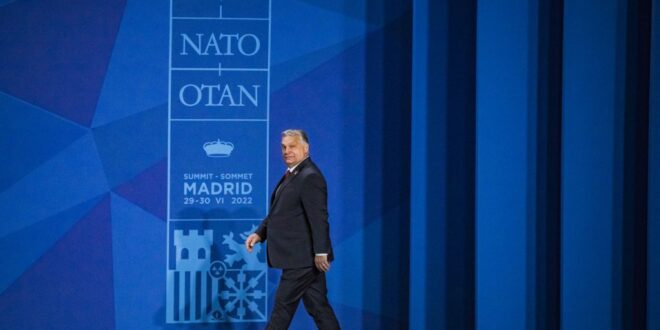

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz—together with its coalition partner the Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP)—has a strong majority in the National Assembly. Moreover, Fidesz has become a kind of a one-man party that will comply with its leader’s wish, with a satellite KDNP that will always follow. If Orbán wanted ratification passed earlier, he could have easily done so.

In fact, all parliamentary parties—as confirmed by Deputy Speaker Csaba Hende—seemed to be aligned in favor of Finland and Sweden, except for the far-right Our Homeland Movement, and their votes are not enough to prevent ratification. When the opposition and foreign media asked after several delays about the timeline for the ratification, the ruling Fidesz, including Gergely Gulyás, Orbán’s chief of staff, indicated that it would be done by the end of 2022. That dragged out into early 2023 and, finally, into late March—but only for Finland. In the meantime, several Fidesz lawmakers began raising reservations regarding Finland and Sweden’s bid, which came in handy for Orbán, who could then start saying Hungary needed more time to deal with ratification.

Follow the EU money

Does Budapest have a particular issue with Sweden’s or Finland’s accession? It does not appear so. Hungary has supported expansion before, and nothing is publicly known that accounts for the current delay. Diplomats who were in touch with their Hungarian counterparts on this particular question told me they are not aware of anything substantial, aside from concerns related to occasional Finnish and Swedish critiques of democratic backsliding and the erosion of rule of law in Hungary—a mainstream position within Europe. As the pressure from allies grew—including several NATO members that recently asked for an explanation from Hungarian ambassadors—Budapest gradually picked that line. Orbán’s political director in a recent Twitter post pointed out a few of the concrete cases from the past where Swedes, including Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson, were not mincing their words in criticizing Hungary. But on March 23, Kristersson met his Hungarian counterpart at the EU summit in Brussels and hoped for more clarification on the hold-up. He commented afterward: “I didn’t get an actual explanation, only the message that they have no intention of delaying any country’s accession… I don’t see any reason for the delay.”

Hungary’s obstruction does not, then, seem to be about Finland or Sweden specifically. Orbán would likely equally interfere if there were other countries joining. For him, it seems to be a matter of questioning liberal and democratic values and the related world order that NATO is here to defend. It’s part of his balancing act between the West and the rest, a way to show—both abroad and at home—that Hungary has a voice that others should hear and respect.

Hungary is also suspected of using its obstructions as a bargaining chip, and likely less in relation to NATO or the United States than with respect to the EU. Orbán may hope that the bargaining chip of ratification can help unlock part of the fifteen billion dollars envisioned by the EU for Hungary from COVID recovery and other funds. That pot of funding includes free grants as well as cheap EU loans but is now frozen over concerns about the rule of law in Hungary. The European Commission linked the release of part of this money to conditions such as strengthening judicial independence and tackling corruption.

In this context, it’s interesting to hear from Budapest that parliament could not properly focus on NATO’s enlargement now because it must rush implementation of the reforms requested by Brussels, as the European Commission should have started the evaluation process on March 15. The reality seems to be, instead, that Budapest did not care for a long time about the Commission’s requests and now could really feel under pressure.

It’s also worth remembering that Sweden currently holds the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union, thus some in Budapest may have thought that Stockholm could be of more use than Helsinki in delivering the frozen funds. Yet this is not so much the agenda of the Council and the presidency, but rather of the Commission.

The world saw Budapest playing a similar game many times recently when stalling the EU sanction packages targeting Russia or opposing nineteen billion dollars of financial aid to Kyiv. And there’s a pattern: In the end, a compromise was always reached with Budapest not leaving empty-handed.

In Turkey’s shade

The news of Hungary’s readiness to initiate the ratification of Finland came just after Erdogan announced Turkey’s decision to do so. There were more concerns regarding Sweden in Budapest, but no talk about splitting the two candidate countries’ accession. A Hungarian parliamentary delegation went to Stockholm and Helsinki recently, with Hungarian lawmakers sending positive messages afterward regarding the ratification. That makes the current Hungarian decision all the more surprising. Orbán uses Erdogan’s shade. Without Turkey hindering enlargement, Hungary would probably be already on board. Orbán could have dragged it out for a while but does not seem to want to be the last one to ratify.

It is too much to say that Orbán is merely following Erdogan. He’s playing his own game, developing his own art of the deal, and hiding behind Turkey. But if Turkey proceeds to Sweden’s ratification after its May 14 parliamentary and presidential elections—and hopefully before the NATO summit in Lithuania in July—then it is likely that Hungary will do the same, though Budapest may seek its own sweetener for doing so.

At a business forum in Budapest this month, Orbán said: “I understand the need to rebuild Russian-European relations after the war but that’s far from realistic… That’s why Hungary’s foreign and economic policy need to think hard about what sort of relations we can establish and maintain with Russia in the next ten to fifteen years.” A few days later, reports emerged that Budapest is considering whether to give French and German companies a larger role in the enlargement of its Soviet-designed Paks nuclear power plant, where two new reactors are slated to be built by Russian state-owned Rosatom and financed mostly from a Russian state loan. It would be a positive development if Budapest reshapes a project that gives Moscow strong leverage over Hungarian infrastructure. Yet the move appears to made more out of necessity than virtue, given that the war in Ukraine and Western sanctions call into question the long-term viability of Russia’s role in the project.

Elsewhere, Hungary continues with its leniency towards Moscow. Recently, Budapest was the only EU country to push back against the International Criminal Court arrest warrant against Putin, preventing the European Union from issuing a joint statement. Hungary also reiterated its opposition to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg’s decision to convene a session of the NATO-Ukraine Commission next week.

Even if Hungary does finally approve NATO enlargement for both Finland and Sweden, the allies should not get their hopes up too high for a more cooperative approach overall. This pattern of obstruction will likely arise in other situations for other countries. That’s why Hungary should not be underestimated as mere mirroring of Turkey. The problem of an unreliable Hungary will long outlast this foot-dragging over Sweden and Finland, and allies should start looking for appropriate tools to deal with an outlier that’s weakening the system from within.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News