Ahead of the war crimes trial of ex-President Hashim Thaci and three other former guerrilla leaders, there is widespread distrust of the Hague-based Kosovo Specialist Chambers, which many Kosovo Albanians see as biased.

Sejdi Zymeri’s house in the village of Likovc/Likovac is close to where the Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA used to have its headquarters in the Drenica region, the guerrillas’ wartime heartland.

His house was used as the KLA’s main hospital and Zymeri can’t hide his emotions when he speaks about the wounded fighters who were treated here – “the one who survived the wounds and the others who died”.

Zymeri is furious about the upcoming war crimes trial of four former KLA leaders at the Kosovo Specialist Chambers in The Hague, which was set up to try crimes committed by members of the wartime guerrilla force.

“This court only exists to humour Serbia. It’s just a political creature,” he told BIRN.

“But let’s see what can be proved,” he added.

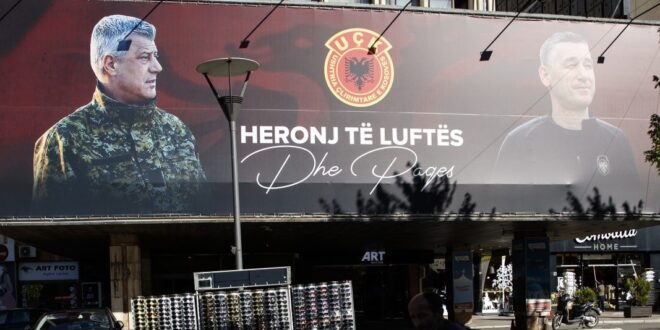

Posters supporting the accused – Hashim Thaci, Kadri Veseli, Jakup Krasniqi and Rexhep Selimi – have been put up along the road that leads to Likovc/Likovac.

All four men became senior politicians after the war: Thaci became Kosovo’s president, Veseli became parliamentary speaker and leader of the Kosovo Democratic Party, Krasniqi was chairman of the national council of the Social Democratic Initiative, NISMA party, and Selimi was the head of the Vetevendosje party’s parliamentary group of MPs.

They are accused of bearing responsibility for murders, torture, illegal detentions and other crimes committed at wartime KLA detention centres.

For Zymeri, as for many others in Kosovo Albanians, the so-called ‘special court’ represents an attack on the KLA’s righteous struggle against Serbian oppression. Since it was established, frustration has continued to grow with what is seen as a biased institution that will only try ethnic Albanians while leaving many wartime crimes by Serbs unprosecuted.

Shortly after Thaci and the others were arrested in November 2020, huge posters supporting them were put up on public buildings and streets all over Kosovo with the slogan “Freedom has a name”.

Two funds were also set up in December to collect money for the defence – one for Thaci and the other for Veseli – in addition to the unlimited state financial support that Kosovo already offers for people charged by the Hague court. It is not known how much money have been raised and the funds’ organisers could not be reached for comment.

Ahead of the start of the trial, Thaci’s supporters have set up a new campaign, also called Freedom Has a Name, led by two members of Thaci’s Kosovo Democratic Party, Eliza Hoxha and Ismail Tasholli. Hoxha and Tasholli have called a demonstration for April 2.

“We must be aware that the attempt to change the history of our liberation war is a baseless attempt and we must not allow it to happen,” Hoxha said.

“Therefore, on the occasion of the start of the trial of the former KLA leaders, we invite people to a solidarity march for justice,” she added.

Amer Alija from the Humanitarian Law Centre Kosovo NGO said that the atmosphere ahead of the trial is similar to previous cases involving KLA commanders facing war crimes charges in The Hague.

“When political or military chiefs face such charges, there is a kind of support for the defendants,” Alija said.

‘It is a biased court’

Ahead of the start of the trial, Kosovo media has intensified its reporting about the case, emphasising empathy for the accused and their fight for freedom and offering little coverage of the victims.

Some television stations have started new shows focusing on cases at the Kosovo Specialist Chambers. TV news items related to the upcoming trial show mostly footage of Thaci and Veseli during wartime rather than footage from pre-trial hearings in the courtroom.

“In this pre-trial phase, we are seeing that the court is a headline in all the media in Kosovo, giving far more space to the accused than the victims,” Nora Ahmetaj, a transitional justice researcher, told BIRN.

On the streets of the capital Pristina, there was concern about whether the Specialist Chambers, a ‘hybrid court’ that is part of Kosovo’s justice system but based in the Netherlands and staffed by internationals, can actually deliver justice. There was also concern that the court was set up to prosecute Kosovo Liberation Army fighters rather than Serbs who committed the majority of the war crimes in 1998-99.

“I don’t expect anything good from this mechanism because it is a biased court, it prosecutes only one side, and anything that is one-sided cannot be fair,” Sali Bytyqi, an Albanologist, told BIRN.

“I think they should have been dealt with before a court based in Kosovo, a court that would treat all citizens of Kosovo equally,” Bytyqi argued.

“I see this court as selective, biased and full of internal problems. Consequently, I see it as unfair,” said Osman Musliu, an imam.

“If you prosecute or judge the KLA leaders’ war, I expect justice for them, which means their acquittal. But if they are judged based on Serbia’s files, then justice can hardly be served. I am sceptical of justice being done,” he added.

But Halil Matoshi said he believed that the court will “establish the KLA’s untainted position in history as the shield of a nation against which Serbia attempted genocide”

“Yes, there is a chance of justice being done,” he said.

‘A climate of fear’

The Kosovo Specialist Chambers has also stepped up its outreach work ahead of the start of the trial, seeking to persuade Kosovo Albanians that it is seeking justice and has no political or ethnic agenda.

Representatives of the Specialist Chambers have been holding meetings with civil society organisations, media, students and others to explain how the court functions, what is its mandate, what has done to include victims in court proceedings, and to repeat the message that it is an independent court which holds fair and independent trials and is prosecuting KLA members as individuals, not the guerilla organisation itself.

Meanwhile some Kosovo Albanian politicians, public figures and even a few journalists who are supporters of the defendants have visited them in detention in The Hague and have been making statements on social media about what they see at the court’s unfairness.

The Specialist Chambers said it is remaining alert to the impact such visits might have on victims of the alleged crimes and witnesses in the trial.

“KSC [Kosovo Specialist Chambers] takes any attempt to obstruct the progress of proceedings very seriously and judges have on several occasions spoken about a climate of fear and intimidation that witnesses who are testifying before the KSC are facing in Kosovo,” court spokesperson Angela Griep told BIRN.

Previous KLA-related trials in The Hague have been marred by witness-tampering and the heads of the KLA War Veterans’ Association have already been convicted of obstructing justice and intimidating witnesses by the Specialist Chambers, although they are appealing.

Kenneth Andresen, a professor at the University of Agder in Norway who is known for his research on Balkan affairs, said that the fact that the court was established to prosecute people from one ethnic group helps to reinforce a hostile atmosphere within Kosovo.

“I think it is a tense situation because many Kosovo Albanians see this court as unfair. So no doubt ethno-nationalism can increase after this trial starts,” Andresen told BIRN.

When the Kosovo Assembly voted in 2015 to establish the Specialist Chambers, the Pristina authorities explained it as a way to clean up Kosovo’s image.

The special court’s establishment came in response to serious allegations raised by a Council of Europe report in 2010 written by Swiss senator Dick Marty about crimes allegedly committed by KLA members. A European Union task force then looked into Marty’s allegations and concluded there was enough evidence for prosecutions for offenses like murders, abductions, illegal detentions, and sexual violence.

Kosovo’s political leaders agreed to set up the court under huge pressure from the country’s Western backers, but in 2017, President Thaci tried to overturn it, but failed.

Gezim Visoka, a Kosovo-born professor of peace and conflict studies at the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University, said that there is a risk of an increase in ethno-nationalist rhetoric around the trial.

“It’s part of the transitional justice process which often offers opportunities for groups in conflict to reinforce antagonistic and anti-peace narratives,” Visoka told BIRN.

But he also predicted that there could be “an intensification of the work of Kosovo’s institutions in prosecuting war crimes as a counter-response to the Special Court, and strategic actions to document and pursue overlooked war crimes”.

Meanwhile in Serbia, the trial of Thaci and the others has attracted little coverage so far. Apart from factual information about the start date and a few sensationalist reports by tabloid-style TV stations, the impending prosecution of Serbia’s wartime foe has not sparked great interest in the country’s media.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News