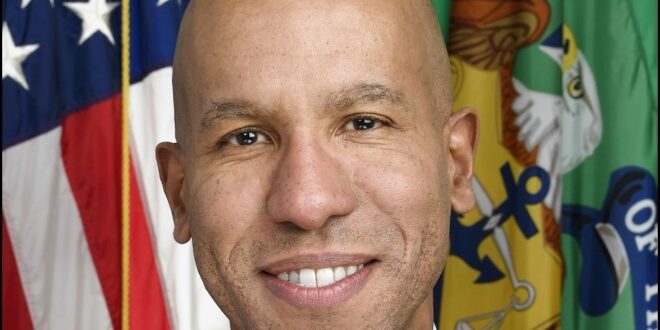

Brian Nelson is the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence. Prior to joining Treasury, he was the Chief Legal Officer at LA28, the organizing committee for the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Los Angeles. His previous government service includes roles as a senior policy advisor, policy chief, and general counsel in the California Department of Justice. There, he oversaw key national security initiatives, including efforts to combat transnational criminal organizations, dismantle human trafficking networks, and build state and international partnerships to stop money laundering and high-tech crimes. Under Secretary Nelson also led a number of efforts to enforce and then reform financial regulations in the aftermath of the national foreclosure crisis in the late 2000s.

Earlier in Under Secretary Nelson’s career, he was a special counsel and then deputy chief of staff of the National Security Division of the U.S. Department of Justice. Following clerkships at the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, Brian began his career at Sidley Austin’s D.C. office as an attorney in information privacy, national security, and appellate practices. He received his bachelor’s degrees from UCLA and his J.D. from Yale Law School.

CTC: You assumed the role of Under Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence at the end of 2021. What have been TFI’s priorities over the first year and a half of your tenure as pertains to the CT realm? How is Treasury responding to the shifting CT landscape?

Nelson: The Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence’s (TFI) mission is to enhance national security by applying Treasury’s unique policy enforcement, intelligence, and regulatory tools to identify, disrupt, and disable terrorists, criminals, and other national security threats to the United States and to protect the U.S. and international financial systems from abuse by bad actors. TFI marshals the Department’s intelligence and enforcement functions with the dual aims of safeguarding our financial system against illicit use and also combating corrupt regimes, terrorist facilitators, weapons of mass destruction proliferators, money launderers, drug kingpins, and other national security threats.

So while TFI was formed with a specific terrorist financing focus after the 9/11 attacks, the scope of our work has really evolved over time. One of TFI’s core missions is to safeguard the domestic and international financial systems from abuse and we do this by identifying and closing vulnerabilities that illicit actors use to support their networks. As such, while today’s conversation, of course, is focused on CT and TF [terrorist financing], I just want to emphasize that it’s hard to discuss that topic without looking at the entire anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) picture. Criminals and illicit actors are using all means to raise funds, which impacts money laundering and other illicit financial activities as well.

The demands for my office’s expertise have really grown quite exponentially in the last several years. CFT remains an important part of our work here, but more than ever, it’s one aspect of a broad set of priorities. And it is difficult to completely separate it as other priority adversaries and criminals use similar techniques to exploit AML/CFT vulnerabilities similarly as terrorist financiers. So while some things have changed in the CT landscape, some things have stayed constant: Terrorist groups continue to try to exploit vulnerabilities in the international financial system as well as jurisdictions with weak governance to raise, move, and use those funds. Likewise, TFI continues to use our tools strategically both to disrupt the financial operations of specific networks and on a more systemic level to close the regulatory loopholes and vulnerabilities which allow these groups to use the formal financial system in the first place.

To maximize our resources and effectiveness, we have really focused our efforts on key facilitators, regional financial hubs, and building partnerships and capacity with priority jurisdictions. This has required a coordinated effort here across all components of Treasury, including our policy, intelligence, sanctions, and enforcement offices. It has also required working closely with other U.S. government agencies to develop a shared understanding of terrorist financing risks and threats, pursue opportunities to disrupt TF, and support interagency CT efforts.

Internationally, Treasury—in coordination with the departments of State as well as Justice and other interagency partners—works bilaterally as well as multilaterally to share typology and transactional information and to engage and build capacity so our foreign partners can take their own actions to dismantle TF networks and prevent terrorist access to the international financial system. Engaging our foreign partners—again, bilaterally and multilaterally—is key to increasing our collective TF risk understanding, maximizing the impact of our actions, and enabling our partners to take their own actions. Just as an example, we have prioritized building up partner capacity to identify and disrupt TF threats through our Terrorist Financing Targeting Center, the TFTC, which is a multilateral forum among the United States and the Gulf countries.

Our multilateral engagement through a variety of international fora as well as these bilateral conversations with our key partners allows us to share lead information and investigative best practices that are designed to build partner capacity. This range of engagements has resulted in better coordination and more effective sanctions and other disruptive outcomes. This is something that we looked at closely through a review of our sanctions’ authorities in particular, and it has also created avenues to engage countries on other priority illicit finance issues.

CTC: Can you describe your career trajectory and how that prepared you for the role you’re now in? What lessons have you learned along the way and what advice would you offer to professionals in this field, specifically the CFT field?

Nelson: Thank you for that question. The first week I started law school was the week of 9/11, so it really shaped my desire to serve our country. Once I got out of law school, I spent a brief moment in private practice before having the opportunity to serve in the Department of Justice, working in the national security division. This was 2009, 2010, 2011 and one of my reflections was that we were seeing terrorist groups that were still plotting threats directly to the U.S. homeland. We were nine, 10 years out from 2001, but we were still seeing that they had the resources and the ability to attempt to strike us here at home. Over my time, in just three years, the capacity of those groups to do that diminished significantly. The thing I took away from that experience was, while the Department of Justice was doing incredible work with partners and colleagues, it was the Treasury Department that had cut off the money, and that really starved a lot of these terrorist groups from frankly having the capacity to attempt to strike the homeland.

I left federal service for the State of California and there worked on transnational criminal organizations. From that perspective, I moved from seeing how sanctions were effective against international terrorist groups to how important our AML/CFT tools are to go after the drug trafficking organizations and human smuggling operations and the like. I also got to work with federal partners from the state level.

Collectively, those two experiences were the things that really drove home for me that these tools that Treasury employs are incredibly effective in supporting and preserving our national security and that it would be an honor to be able to lift up the work and to continue to try to effectively hone the use of those tools. In California, I was working for then Attorney General Kamala Harris, and so when I was invited back to Washington, D.C., to continue to support this work, I was profoundly honored to be nominated by the president to lead TFI.

Regarding lessons learned, I think the thing that I carry with me is that the more we can uplift the work of colleagues across the national security apparatus of our government the more effective our fight will be. For me more personally, the lessons learned are to focus on the work, focus on doing that work in a spirit of collegiality and respect, and just go where the opportunities present themselves. You never know: When I moved to California, I wasn’t planning on coming back to D.C. necessarily, but I wanted to continue to be able to serve our country in a new capacity. So I think just focusing on that, focusing on the mission, and trying to execute against it as effectively as you can is really, truly the real advice.

The other thing is just to have a suite of experiences. You don’t have to do one thing for your entire career, and there are so many ways to get after and really support our national security mission. Seeing it from a number of different perspectives I think provides useful insights into how we can more effectively work here in our own government and with our international partners to execute this mission with the tools that we have.

CTC: How does Treasury prioritize resources to combat the various terrorist organizations active across the globe? Are some groups more susceptible than others to disruption through traditional Treasury tools?

Nelson: It’s a great question, and as I noted earlier, there are a variety of threats we continue to monitor and, frankly, they all have different points of pressure. But their tactics, their techniques, their procedures for financing their illicit activities still overlap. Financial disruption is more effective against more centralized terrorist organizations, as you can imagine: those that rely on the international banking system. This allows us to leverage the central role that U.S. banks play in cross-border financial activity.

Just as an example, Hezbollah’s leader made an unprecedented call to his supporters pleading for fundraising efforts to be stepped up after highlighting the financial pressure that’s been imposed by our own sanctions.1 And we’re aware that Hezbollah media and military officials are complaining of the pay cuts, so we know it’s working.

We’ve also used direct engagement to complement our own actions and maximize impact. Working with partners has enabled arrests, freezing of assets, prosecutions, and domestic designations of terrorists and terrorist financiers operating in their own jurisdictions. For example, in January and then again in May of this year, Treasury worked with Turkish authorities to take joint action to disrupt financial activities of ISIS and other terrorist groups operating in that region.2

But financial sanctions have been less effective against terrorist groups that rarely use or do not require use of the regulated financial system for the reasons I’ve noted. Some groups raise revenue locally and do not engage in cross-border financial activity or travel internationally, and that is necessarily going to limit the practical impact of our tools.

CTC: How does Treasury approach combating terrorist financing in regions where tools like sanctions may have limited disruptive impact? In addition to sanctions, what other tools does Treasury employ to combat terrorist financing?

Nelson: Going back to the attacks of September 11th and the focus on executing a whole-of-government effort to counter terrorism, which was strengthened by the USA Patriot Act in 2004, TFI has a broad range of powerful economic tools—obviously through economic sanctions, but also inclusive of anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism measures, enforcement, foreign engagement, policy coordination, asset forfeiture, and intelligence and analysis, among others. We remain still the only country that combines all of these economic authorities, including an intelligence department, within our own Department, which helps the United States respond effectively and nimbly to the greatest illicit finance and national security threats that our country faces.

While sanctions are an effective tool and truly a critical part of our work in this space, we have many different tools that we can leverage to protect the U.S. financial system from illicit financial activity such as terrorist financing. We work very closely with our U.S. law enforcement counterparts and engage with financial institutions to help them better protect and report suspicious financial activity. We can, and often do, utilize tools such as advisories and information-sharing mechanisms through Treasury’s Financial Intelligence Unit, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network—otherwise known as FinCEN. FinCEN works to promote national security through the strategic use of financial authorities to collect, analyze, and disseminate financial lead information. These information exchanges—both with private sector and federal law enforcement—really offer the opportunity to share red flags and typologies, which in turn can enable their own work to identify suspicious activity by the financial institutions themselves. And most importantly, this information is invaluable to promoting national security by aiding law enforcement agencies in their efforts to investigate and prosecute terrorist financers and other criminals that are abusing the U.S. and international financial system.

Given the gravity and time-sensitive nature of terrorist financing offenses, financial institutions are required to immediately notify law enforcement in addition to filing a suspicious activity report with FinCEN. This demonstrates the strong public-private partnership between FinCEN, law enforcement, and financial institutions on such an incredibly serious issue. And then similarly, information from Treasury’s Terrorist Financing Targeting Program, the TFTP, has been and continues to be instrumental in supporting specific investigations of terrorist financing networks, enabling us to better understand the movement of funds that facilitate more effective disruption.

We also leverage our participation in multilateral bodies, such as the Financial Action Task Force, the FATF, which is the international standard-setting body for AML/CFT, to strengthen international cooperation and promote effective legal and regulatory regimes. This type of multilateral cooperation is incredibly important to tackling systemic issues that make jurisdictions susceptible, frankly, to abuse for TF purposes. Given the international financial system’s interconnectedness, deficiencies in one jurisdiction, unfortunately, can be exploited to gain entry and abuse the broader international financial system for terrorist financing and other illicit purposes.

CTC: How is Treasury responding to the growing threat of domestic violent extremism?

Nelson: Combating domestic terrorism is a priority for the Biden-Harris administration, and we here at TFI have been applying lessons learned from our experience with international terrorism and combating other criminal actors in this involving challenge, while respecting the vital constitutional protections for all Americans. We very recently hosted a roundtable with public and private sector partners, where discussions focused on how domestic violent extremists (DVEs) and racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists (RMVEs) have raised, moved, or used funds. That roundtable included focusing on the use of virtual assets in particular and some of the challenges in identifying and reporting the misuse of virtual assets by these groups, along with potential opportunities for collaboration.

Developing a shared understanding of money laundering and terrorist financing risks among relevant public and private stakeholders is, in our view, the foundation of an effective AML/CFT regime to protect the financial system from abuse by illicit actors including DVEs and RMVEs. This is not unlike the public-private partnership that establishes and is the framework for all of our AML/CFT work.

To further promote this risk understanding, we also launched a public landing page3 on Treasury’s website of select reports and assessments for private and public sector entities seeking to develop a better understanding of DVEs, their foreign analogs, and associated financial activity.

Lastly, we also collaborate with our State Department colleagues to assess whether foreign organizations and individuals linked to domestic terrorist activities can be designated. This includes the recent June 2022 designations of two supporters that were linked to the Russian Imperial Movement.4 And then we also regularly engage with foreign governments to identify and disrupt foreign individuals or entities sending money to support the training or recruiting of U.S. persons, which again is work that we’ve done in other contexts as well.

CTC: How does Treasury assess the threat of digital assets being abused by terrorist organizations to raise and move funds?

Nelson: Digital assets create a complicated environment, to be sure, as we recognize both the potential benefits and challenges brought on by this new and emerging technology. Treasury is focused on encouraging responsible innovation in the digital asset space, while also identifying and assessing potential illicit finance risk and, where appropriate, applying necessary mitigation measures. As virtual assets continue to become more accessible and barriers to entering the crypto market continue to decrease, we need to be mindful of the potential for illicit financial activity. We do have particular concerns about certain underregulated sectors of the market and encrypted person-to-person transfers that don’t require a traditional financial institution intermediary.

To your question, we know that terrorist groups try to exploit emerging technologies for their organizations; this has been true for a long time. And we have seen both domestic and foreign terrorist actors utilize virtual assets to fund their operations. Similarly, U.S. law enforcement agencies have detected an increase in the use of virtual assets to launder the proceeds of drug trafficking, fraud, and cyber-crime, including ransomware attacks as well as other illicit activity, which also includes sanctions evasion.

However, it’s important to contextualize the scale of the problem. We assess that terrorist groups still overwhelmingly tend to use more traditional ‘tried and true,’ if you will, methods of moving funds such as cash and formal and informal banking mechanisms. And then likewise, use of virtual assets for money laundering remains far below that of fiat currency and more traditional methods. But this is an area that we’re watching very closely and we’ll continue to monitor for the foreseeable future.

CTC: How does Treasury mitigate the potential for indiscriminate “de-risking”a by financial institutions from jurisdictions or transactions that may be perceived as a high risk for terrorist financing and other illicit finance?

Nelson: Yes, this is a high priority for the Treasury Department, and it is one that we’ve been working on over the past few years. We are committed to shaping a safer, more transparent and accessible financial system, while at the same time, maintaining and preserving a robust framework to protect the U.S. financial system from illicit actors and bolstering national security. So striking this balance between these two objectives is really a critical piece of making the U.S. AML/CFT framework effective.

This de-risking, as you described it, is also inconsistent with global anti-money laundering and countering terrorism financing standards just generally. From our perspective, widespread access to well-regulated financial services facilitates financial inclusion and reduces the incentive to use unregistered financial services. Financial access also ensures that well-regulated financial systems remain central to international finance, and these, as I’ve described, are really all U.S. public policy goals and support the use of our tools to go after illicit actors. We also just earlier this year released the 2023 De-Risking Strategy, which I am proud to say is the first of its kind, and it examines this phenomenon and offers policy options to address it. The things that we want to do is make sure that banks take a risk-based approach when it comes to AML/CFT policies in high-risk jurisdictions. They can do that by analyzing and managing the risk of clients in a targeted manner. This will only enhance our ability to detect and combat TF while ensuring financial services are available and accessible to those who need them.

We’ve also taken significant steps in the past several months to facilitate the delivery of humanitarian assistance to vulnerable populations. One example of our commitment on this issue led to the adoption of broad humanitarian authorizations within our U.S. sanctions programs and the adoption and implementation of U.N. Security Council Resolution 2664 to approve humanitarian exemptions imposed by the United Nations sanctions regimes.

CTC: We’ve spoken a lot about how Treasury combats non-state terrorist actors. How does Treasury’s approach differ when combating the funding of state actors, and their proxies, such as Iran and DPRK? What challenges have you faced? What progress has been made?

Nelson: For better or for worse, criminal actors, regardless of state or non-state association, are exploiting the same vulnerabilities and relying on similar typologies to raise, move, and use funds while facilitating their illicit purpose. Therefore, a strategy to counter state actors and their proxies involves a similar coordinated effort within Treasury and with partners.

Specifically on the DPRK, we are focused on using our tools and authorities to root out Pyongyang’s WMD procurement networks, revenue generation schemes, malicious cyber activity, sanctions evaders, and human rights abuses, and probably a whole list of malign activity that they’re engaged in. And this year, we’ve designated more than a dozen individuals and entities involved in obfuscating DPRK’s revenue generation, its weapons facilitation, and its malicious cyber activities. We coordinated these efforts with our close partners and allies, and several of these destinations were jointly rolled out with the Republic of Korea. Treasury has also taken other actions to inform the public and private sector of the DPRK’s illicit financing through our Decentralized Illicit Finance Risk Assessment, our National Proliferation Financing Risk Assessment, and the DPRK IT Workers Advisory. Almost all of our risk assessments have a DPRK angle of one flavor or another.

On Iran, Treasury has taken a robust and comprehensive approach to combating the regime’s state sponsoring of terrorist and illicit activity. Over the past several years, we’ve disrupted several IRGC-QF financing schemes with wide-ranging networks. Our actions have sought to restrict the channels by which our adversaries can access the international financial system and have primed the private sector to be aware of the sanctions-evasion typologies employed by Iran and other adversaries.

We continue to regularly engage frontline industry, foreign governments, and international organizations on Iran and DPRK sanctions-related issues.

CTC: In January 2023, the Wagner Group was designated a transnational criminal organization by Treasury.5 Some have asked whether it should be further designated as a foreign terrorist organization,6 which would expand Treasury’s sanctioning powers against it. And there has been some discussion here and abroad of it being designated a terrorist group.7 How do you view this question of an FTO designation? Is the current transnational criminal organization designation sufficient for your office to constrain the Wagner Group’s activities?

Nelson: It’s a great question, and I’ll have to defer to my State Department colleagues on this question as they’re the lead agency for designating entities as FTOs. But as you mentioned, OFAC [Office of Foreign Assets Control] designated the Wagner Group as a Significant Transnational Criminal Organization in January, further reinforcing sanctions imposed on the group including by G7 partners and allies. Our sanctions continue to help expose the Wagner Group’s abuses, and by aggressively targeting the group’s support networks, we are doing our part to disrupt its operations. But clearly, this—as you noted—is an ongoing priority area for the administration.

CTC: What financial threat do you wish was better understood by or received more attention from policymakers, practitioners, and the public?

Nelson: There are a number of threats that I would say should receive more attention from larger swaths of people, but one area that is particularly important is that deficiencies in AML/CFT regimes globally create widespread opportunities for regulatory arbitrage, which allow our adversaries and other illicit actors to abuse the international financial system and threaten our national security. It really is that principle of the weakest link. However, as the largest economy in the international financial system, we, the United States, bear a responsibility to close deficiencies in our own domestic AML/CFT regime while also increasing transparency and accountability in the U.S. and international financial systems.

So at the end of the day, a strong AML/CFT framework makes it harder for illicit actors to abuse the U.S. and international financial systems while also allowing us to target more effectively those who have nevertheless slipped through. To that end, Treasury has taken a number of steps to assess our domestic AML/CFT regime and identify potential deficiencies, then taking steps to address any of the deficiencies that we have identified.

For example, there is a problem of so-called gatekeepers. These are the professional service providers that facilitate financial activities. These types of individuals and entities are not covered by comprehensive and uniform AML/CFT obligations and are routinely involved in company formation and complex financial transactions and corporate activities that can be used to facilitate money laundering.8 Treasury is also working to implement the Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting regime, mandated by the Corporate Transparency Act of 2020, and we are also working towards bringing just greater transparency to the residential and real estate market and evaluating whether and how we should impose AML-CFT obligations on certain investment advisors. So while addressing our own domestic regulatory deficiencies, we also continue to engage multilaterally through participation in the Financial Action Task Force and bilaterally with our partners on the importance of really advancing these AML/CFT reforms to better protect the entire international financial system from abuse.

And as you can probably sense, TFI’s founding mission absolutely does persist. It just happens to be nested in this broad swath of priorities against which the United States is using Treasury TFI tools. As with any organization, we have to continue to evolve to meet the growing demand for the use of these tools and continue to meet the demand for the use of these tools in the context of national security challenges. In this, I must acknowledge our incredibly strong staff and colleagues who are dedicated to this mission and are strategically applying this expertise, our tools, our authorities to advance our national security and foreign policy objectives. CTC

Substantive Notes

[a] De-risking is “the practice of financial institutions terminating or restricting business relationships indiscriminately with broad categories of clients rather than analyzing and managing the risk of clients in a targeted manner.” See “The Department of the Treasury’s De-risking Strategy,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, April 2023.

Citations

[1] Editor’s Note: See “Hezbollah calls on supporters to donate as sanctions pressure bites,” Reuters, March 8, 2019.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News