A Conversation With Stephen Kotkin

Stephen Kotkin is a preeminent historian of Russia, a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution and Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, and the author of an acclaimed three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin (the third volume is forthcoming). Executive Editor Justin Vogt spoke with him earlier today about the dramatic events that have taken place in Russia in the last 24 hours. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Yesterday, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of the mercenary Wagner organization, launched a rebellion against the Russian military and a direct challenge to Russian President Vladmir Putin’s rule. As of this afternoon, it seems he has at least temporarily halted what appeared to be a march toward Moscow. It remains exceedingly difficult to know where events in Russia are headed. The situation is fluid, it is early, and we don’t want to jump to conclusions. Still: How could this have happened?

Prigozhin is improvising. Maybe he’s stopped the progress toward Moscow, but now what? Back to base camps, he says. OK: but he’s still in charge. You say coup, I say putsch. You say tomato, I say tomahto: let’s call the whole thing off—but just for now.

But he already succeeded in walking into Russia’s southern military headquarters, which is in downtown Rostov, right in the city. Wagner took the headquarters—and they took it not with guns but essentially with smartphones. The technology has made this a different ballgame. A TV production company is running Ukraine—and doing so with tremendous success, in wartime. Prigozhin’s instrument is Telegram. Putin is famously not on the Internet; he apparently doesn’t understand social media. Big mistake.

The dynamic here is potentially like a bank run. Think about when Silicon Valley Bank collapsed: that was a bank run powered by Twitter. If the Russian army starts to disintegrate in the field, it would amount to a Telegram-powered run on a political-military bank.

If that happens—an immense “if”—Prigozhin could be the gift Ukraine deserves: the crucial alternative to Putin that tests everyone’s loyalties inside Russia, reveals there is little to no actual support for the war among those fighting it on the Russian side, and even unravels things in Moscow. Ukraine’s counteroffensive in its first ten days has been probing weaknesses—alas, probing Ukraine’s own weaknesses, and finding them almost everywhere. But the drive might suddenly look more like slicing through butter if Russians lay down their arms, confused—or, demoralized, just head for home. Ukraine’s counteroffensive faced long, difficult odds; an internal threat to Putin was the one scenario that really favored the Ukrainians. And, well, here we are—or might be.

I have long been calling the Putin regime “hollow yet still strong.” It remained, and remains, viable as long as there is no political alternative. Now, we might see just how hollow the regime is. Putin has unwittingly launched a stress test of his own regime. He had already lost his mystique with the bungling of the aggression against Ukraine. Mystique, once lost, is near impossible to regain. The old cliché about the emperor and clothes. He still possesses enormous power, rooted in structures he built around himself, such as his Praetorian Guard, and those he unbuilt—his razing of the landscape of political possibilities besides himself, and severe repression to demobilize the populace.

Almost every coup fails. The odds are long. But now, at least, there are odds.

There is one thing that all dictators properly fear: an alternative. And Putin, shockingly, after years and years of indefatigably suppressing alternatives, of promoting nonentities to his inner circle to ensure no one could threaten him, has allowed one to take shape. Pinch me.

Authoritarian regimes build up formidable military and security services, but these are purposely divided against themselves by the leader, to control them, to make them dependent on him. The leader deliberately gives them overlapping jurisdictions, heightens their inherent rivalries at every turn, and sits back and watches, usually with glee. But in this case, Putin has conjured up his own nemesis.

I’ve been saying for some time that the way to get Putin’s attention, to destabilize his regime, was to identify and recruit a defector from the inside, a Russian nationalist, a person who appeals to Putin’s base, but one who recognized the separate existence of a Ukrainian nation and state. Preferably a defector in uniform. And Putin has gifted us a candidate.

It’s early. We have to be careful not to indulge in wishful thinking. Coups in Russia have a terrible track record. Globally, almost every coup fails. The odds are long. But now, at least, there are odds.

But what are the alternatives to Putin?

It’s easy to dismiss Prigozhin as a lowlife, a commander of some death squads—militia figures who had been imprisoned for murder or rape and whom he personally recruited in penal colonies. He himself served a long prison term, by some accounts nine years. But he also in some ways represents an alternative that might have appeal: an authoritarian Russian nationalist who recognizes the war is a mistake and, whether fully intentionally or not, effectively ends the war, or at least the current active phase of it. That’s the one kind of person who could threaten Putin—and Putin did nothing as it unfolded in real time, on videos that the whole world watched.

Prigozhin might seem to be an unlikely contender. But in some ways his background is more suitable to the moment than Putin’s. Both are from St. Petersburg, but Prigozhin, despite serving time, is from the intelligentsia. His mother is an artist; she runs a gallery in London. He speaks better Russian than Putin. In terms of social class, he’s actually a level above Putin. And Prigozhin’s artistic side is visible in his videos. He cannot count (his math is terrible, another revelation of his videos). But look at his pithy and pointed vocabulary, his cadences, his ability to assume the role of tough guy, heart-on-the-sleeve Russian patriot, the truth teller who calls out the opportunists, the morons, and the thieves Putin has appointed.

There is one thing that all dictators properly fear: an alternative.

To an extent, Prigozhin appears to have learned from [Russian dissident] Alexei Navalny’s superlative video performances. Navalny is still alive. He is in prison, facing renewed sentencing on trumped-up charges. As long as he’s alive, he too represents an alternative. Another Russian nationalist, of a very different stripe to be sure, but one who also says out loud that the war was a terrible idea and is hurting Russia.

Navalny is, in addition, the invaluable sanctions-lifting card for any would-be replacement for Putin, even if Navalny is not himself that replacement.

What can Putin do to turn things around?

Putin could use his powerful air force, which is still intact, to strike the Wagner forces. It appears the Russian air force has been bombing Wagner forces en route to Moscow. It would be a radical act to strike Prigozhin, holed up in Rostov, the principal military hub in Russia for Putin’s war in Ukraine. Imagine the symbolism of that. That said, an airstrike or a missile strike could end this would-be uprising quickly. And if he doesn’t use the air force decisively, and soon, Putin could lose control over the situation.

Prigozhin does not have the heavy weapons to take Moscow militarily. He has no air force—unless elements of the Russian air force defect to him. He could take Moscow, or at least enter it, for talks or negotiations, but only if he does not meet opposition. That would require the Russian military—soldiers and officers—to choose not to fire on his men and on him. It would mean the FSB (Federal Security Service) decided, or some elements in it decided, to refrain from fulfilling orders of shoot to kill. This seems unlikely, to be honest. The fact that we are even discussing it, however, means it is not zero probability.

We should be concerned that Putin could do something radical.

If Putin does use the air force against Prigozhin, it could also make matters worse for Putin. He’d be bombing his own forces. Rostov is Russia, not Ukraine. There are Russian kids there. The military HQ is smack in the downtown of a populous city, and Russian soldiers and officers are inside the HQ, not just Wagner mercenaries—who also have mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers. Putin wouldn’t be able to censor such an act, because the whole point would be to demonstrate that he is in charge.

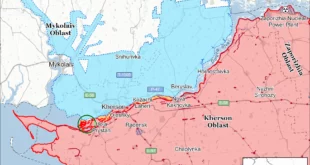

We should also be concerned that Putin could do something radical to distract attention and regain the upper hand. He blew up the Kakhovka dam. What about the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant? Putin could have it blow up and irradiate Ukraine. Much of Ukraine would potentially become uninhabitable for an extended period: radiation is a whole lot worse than contaminated water or the mines Russia has been seeding all over the large swaths of Ukraine they occupy. Ukrainian special forces have tried and failed, multiple times, to cross the Dnieper River and take control of the nuclear power plant.

These are some dire scenarios.

Armageddon not averted but delayed? Armageddon rescheduled? I can scarcely believe I’m mouthing such words. Putin has recently reiterated that government policy on the use of nuclear weapons is in a scenario when the existence of the Russian state is threatened. He equates his personal rule with that of the Russian state.

We do not want to panic or induce panic, of course. I don’t know if the statement of Putin’s regime that he has deployed tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus is real. He only needs to have deployed one. If a tactical nuke is fired from Belarus, is there a case for retaliation against Russia?

Let’s remember: when Putin attempted to assassinate what he deemed traitors in the United Kingdom, he did not have his hit squads use pistols to shoot them or dump arsenic in their tea. He had them use polonium, Novichok. That, too, was a message—not just the fact that he would kill traitors wherever they were, but the “how.”

No matter how Putin responds, it seems like he’s at risk of losing his grasp.

This could peter out quickly. Putin is a survivor. A sense that the Russian state is at risk could rally the various rivalrous factions around him.

Putin, in his video response to Prigozhin, alluded to a moment of danger like 1917—that was when Lavr Kornilov, the commander in chief of Russian forces in World War I, sent forces to the capital, St. Petersburg, to restore order, but only succeeded in further disintegrating the political home front.

Or think of the attempt not long thereafter by Alexander Kerensky to preempt an attempted coup by sending forces to shut down and arrest the Bolsheviks, setting in motion the very coup that Kerensky and his Provisional Government wanted to forestall. The Russian Empire dissolved. If the hard men agree, if they perceive a moment of equivalent danger, not just for Putin but for Russia, they could save him to save the country.

What or who should we be paying attention to know where things are heading?

Watch the security council chief, Nikolai Patrushev. Beijing has not commented yet; now might be the moment for Xi Jinping to decide he does, in fact, have no alternative to a quasi-puppet regime in Moscow. If Putin is going down, Xi might want to preempt less desirable options, like a Western-friendly one. Profound ramifications, potentially, for China.

Watch the Chechen warlord Ramzan Kadyrov, who like Prigozhin runs a large private militia. He professes absolutely loyalty to Putin, but he could help spark a North Caucasus problem. Let’s see if Kadyrov, who has serious health issues, stays in or near Grozny or if he appears elsewhere to play a part. His men are involved in suppressing Wagner, it seems. Kadyrov’s ambitions, incredibly, have been in Moscow. But triggering the North Caucasus could have wide ramifications—for the South Caucasus, for the Levant, for Russia.

Watch Belarus, too. The erratic president, Alexander Lukashenko, might decide the writing is on the wall and suddenly decide to flee, setting off further repercussions. Putin could even try to remove and replace him. And who knows? Lukashenko could even switch sides and turn westward.

Has what’s happened in the past 24 hours changed your view of Putin?

Here’s the bottom line: even if it is now snuffed out, an alternative was allowed to arise. All this unfolded in real time, on video, over months and months. Putin did not intervene earlier and allowed things to get to this point. Stunning. Either he has descended into utter incompetence or he has less operational control than his media machine has been letting on. Or both. I expected him to be better at Authoritarianism 101. I expected him to understand this was the one threat in real time. I expected him to end the games, end the pitting of rivals against each other to control them, because it had become dangerous to him personally. I overestimated him. I would not want to make the opposite mistake and underestimate him now, though.

What is the right historical parallel here?

I already mentioned 1917, because Putin himself evoked it and not the Soviet implosion of 1991, which he lived through and has reflected on often. But the remarkable aspect for me is not just the eerie sense of the distant past that appears so close, yet again, but the tech and media revolution. I look at that Ukrainian TV production company running this war, I look at the production of the January 6 hearings here in the United States—Liz Cheney’s hearings were run by a TV producer, with powerful effect—and I think, “This is how you do national security most effectively now: with smartphones, videos, memes.” All those written and emailed policy briefs, all those meetings of principals and deputies form the sprawling national security bureaucracies, all that spying and cloak and dagger—and, boom: Telegram and a pair of thumbs.

Can Ukraine take advantage of this?

I was not among those persuaded that Ukraine was going to take a bunch of guys who worked in 7-11 equivalents, train them for a few months on how to use the world’s most sophisticated weapons, and send them into frontal assaults against some of the most heavily fortified positions you’re ever going to see. That is, mount an offensive where the enemy knows exactly where you’re going to strike, and has more than enough time to prepare and has prepared, doggedly.

On the Ukrainian side you do not have very large numbers of well-trained troops skilled in combined arms operations, one of the hardest things for any military, but mostly civilians who, for all their courage and will, through no fault of their own have, well, been handed a very tough assignment. Not all of Ukraine’s newly trained brigades have been sent into action. Still, it has not been impressive so far. Yes, Ukraine has no F-16s yet; they are supposed to be coming. But how aviators might fly combat missions with them successfully into the teeth of Russia’s S-300s and S-400s, firing from Russian soil, is beyond me.

We might see just how hollow Putin’s regime is.

We’ve been watching Russian forces in defense learn and adapt, use helicopter gunships very effectively. This should not have but appears to have surprised some analysts. Russian mines have been plentiful and deadly, and used with some sophistication and in immense quantity.

But what if Prigozhin manages to disintegrate the Russian army? What if he manages to destabilize the regime in Moscow? What if, even if he is put down, destabilization and disintegration results, in some form, to some degree, anyway? This could be the gift that Ukraine deserves, the gift that their valor and sacrifice has more than earned. This scenario—the Russian nationalist who abjures the war—is Ukraine’s quickest path to some sort of victory. Then, of course, the question of Crimea would jump to front and center.

What options do Washington and its NATO allies have? Just wait and see?

If Washington, NATO, Ukraine, are seen as backing Prigozhin, in cahoots with Prigozhin, it could have the effect of undermining whatever chances he might have to catalyze an end to the aggression. So the response has been properly to just let it unfold, with a bit of tongue in cheek commentary out of Kyiv, but otherwise bite-the-tongue restraint in D.C. and Brussels.

Behind the scenes, of course, it’s 24/7 very close monitoring of everything and anything, and intense consultation. Twelve hours, 24 hours, 36 hours, of nail biting. But after all the Sturm und Drang, we could be right back where we started: Putin in power in Moscow and Ukraine facing a counteroffensive that will be very difficult to pull off.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News