Will a Toughened China Strategy Be Enough?

In 2020, the European Union’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, called on Europe to forge its “own way” with China and distance itself from the “open confrontation” approach pursued by U.S. President Donald Trump. The goal of Borrell’s “Sinatra doctrine,” so named in reference to the song “My Way,” was for the EU to avoid becoming either “a Chinese colony or an American colony” amid a Cold War–like struggle between Washington and Beijing. Striking such a balance, Borrell argued, would allow Europe to retain the benefits of strong economic ties with China, which he and most other European policymakers at that time saw as far outweighing the risk of giving Beijing too much influence.

Three years later, the geoeconomic landscape is very different—as are EU perceptions of China. The European bloc has grown disenchanted with Beijing’s opaque handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, its implicit support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and its increasingly assertive foreign policy. The EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, hastily inked in December 2020 before U.S. President Joe Biden took office, was put on hold after China imposed sanctions on EU lawmakers and is now on indefinite hiatus. The “Russia shock” has jolted leaders to attention, exposing the unsettling reality that Europe’s biggest problem is not a pushy ally across the Atlantic but rather deep vulnerabilities to potential Chinese coercion.

Over the past six months, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has led the charge to reorient the EU’s stance toward China. In a speech in March, she championed a plan to safeguard Europe’s economic security by “de-risking” its relationship with China—that is, reducing critical vulnerabilities resulting from overdependence, especially in the health, digital, and clean-technology sectors, and deterring economic coercion, while seeking to cooperate on broader challenges such as climate change. Rather than pitting Europe against the United States, as Borrell had, von der Leyen sought to bridge the transatlantic divide—at least rhetorically. And indeed, her approach has resonated with the Biden administration, which has adopted the term “de-risking” to dispel fears that it is pushing for “decoupling,” a complete severing of economic ties with China.

Yet European strategy toward China is far from settled: European policymakers continue to vigorously debate how far the EU should go to diversify its economic relationships and curtail trade and investment with China in critical areas. And despite EU efforts to define a new China policy, Germany remains the real linchpin: as the continent’s economic engine and its largest exporter of goods to China, Berlin will play an outsize role in determining a new approach. In July, after half a year of delay, Germany finally published its new China strategy, which calls for greater coordination with Brussels and Washington while preserving deep economic ties and overall cooperation with Beijing. The success or failure of this approach will hinge on how it is implemented: Berlin must live up to its new, tougher rhetoric and avoid repeating the costly mistakes it made with Russia, which on the eve of the invasion of Ukraine was supplying more than half of Germany’s natural gas and was not taken seriously by Germany as a potential security threat to Europe. Should Berlin not walk the talk but instead continue to prioritize economic benefits at the expense of unmitigated geopolitical risk exposure against a more assertive China, it could wind up just as vulnerable to economic coercion in another security crisis, perhaps over Taiwan. Whether the European way with China turns out to be the right way is in large part up to Germany.

DANGEROUS DEPENDENCIES

China is the EU’s largest partner for imports of goods and accounts for more than half of the import value of the bloc’s 137 most foreign-dependent products. This dependence on China underscores Beijing’s diverse leverage, including its potential to weaponize its position as a dominant supplier of critical minerals and other key industrial inputs, as Russia did with oil and gas. Over the last two years, the Biden administration has worked with U.S. allies and partners to tighten export restrictions to China, which has exacerbated China’s bottlenecks in developing technology. In response, Beijing has recently hit back with export controls on gallium and germanium, essential elements for the production of chips, radar, and fiber optics, demonstrating its willingness to use coercive economic measures that escalate tensions. As major world powers retreat from hyperglobalization and economic policy becomes more security-oriented, Germany and other EU countries should be wary of maintaining unfettered economic ties with China.

This concern has not been lost on policymakers and industry leaders in Germany, who have expressed mounting doubts about the country’s increasingly unbalanced economic relationship with its top trading partner. Germany’s consistent overall trade surplus contrasts starkly with its growing trade deficit with China, which hit a record high of $93 billion in 2022—a staggering 120 percent increase over the previous year’s figure, reflecting a new and alarming dependence on imports from China. China’s expanding investments in German strategic sectors have also stoked national security fears, notably since the Chinese appliance maker Midea Group acquired Kuka, one of Germany’s most innovative robotics engineering companies, in 2016.

Despite these creeping vulnerabilities, Berlin has shown little appetite for overhauling its economic relations with China. German manufacturers are struggling with high energy prices and the negative effects of the Biden administration’s industrial policies, including those introduced through the Inflation Reduction Act, which are designed to favor American businesses. Moreover, leading German automakers still consider China their second home market, even as they grapple with lower profitability and declining sales in the country after long ignoring the competition from Chinese EV companies. Amid uncertainty about the strength of the German economy—which which entered into technical recession in the first quarter of 2023—many German policymakers remain anxious about the nation’s economic resilience. Household names like Volkswagen and the chemical manufacturer BASF are particularly exposed to economic coercion or a sudden disruption of trade with China: Volkswagen derives at least half of its annual net profit from the Chinese market, and BASF invested a record high 10 billion euros in China in 2022. Overall, German investments in China are also increasing.

Germany’s three-party coalition must thread a difficult policy needle: tread cautiously with its most important economic partner but heed the growing economic risks of integration. Germany’s first national security strategy released in June mentioned China only in a cursory way, and Taiwan tensions not at all, raising expectations for the long-awaited China strategy. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has repeatedly called for a recalibrated approach to China, but it is the Greens, who lead the foreign and economic ministries, that are driving the domestic debate on China, putting Scholz’s more cautious Social Democrats in zugzwang. The Green-led Foreign Ministry crafted the China strategy, and its assessments of the challenges posed by Beijing are surprisingly clear-eyed. In a passage that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago, the document acknowledges that China is “pursuing its own interests far more assertively” and attempting “to reshape the existing rules-based international order.”

Berlin does not want to become a part of a confrontational “bloc” against China.

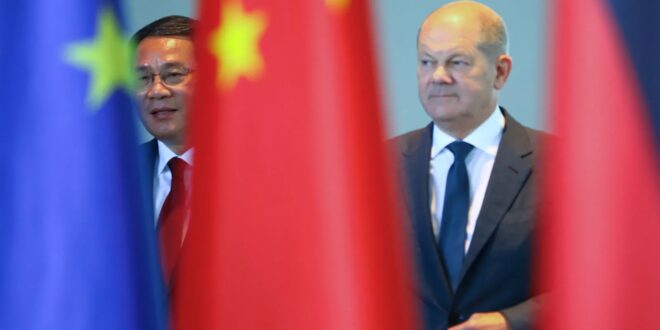

Tellingly, the German government postponed the strategy’s (already delayed) release until Chinese Premier Li Qiang visited Berlin for the seventh round of consultations between the two governments, his first trip abroad since taking office in March. In a meeting with about a dozen German industry leaders, Li proposed that corporations, not governments, should be in charge of de-risking and that de-risking requires strengthening cooperation, whereas decoupling would not work. Berlin’s aim in welcoming Li was to reassure Beijing that Germany does not seek decoupling and still sees China as a partner for the German economy and to address challenging issues such as climate change. Scholz’s Social Democrats were concerned about confrontational wording in the China strategy and watered down the initial version drafted by the Foreign Ministry during drawn-out debates within the country’s governing three-party coalition until its eventual publication in July.

The strategy aims to recalibrate Germany’s increasingly unbalanced economic relationship with China and align it with Germany’s broader geopolitical aims. At the same time, Chancellor Olaf Scholz is careful not to put China into the same box as Russia, whose invasion of Ukraine prompted the Zeitenwende, or sea change, in Germany’s security and defense policy. The strategy explicitly commits Germany to economic de-risking as its guiding principle and aims to reduce the country’s vulnerabilities in areas where dependence on China could pose national security threats. In large part, the strategy embraces the sharper instruments endorsed by the European Commission, including coordinated export controls. But it stops short of requiring screenings for outbound investment, as called for by the European Commission, making a commitment only to “consider” them.

Obligatory stress tests and mandatory reporting for companies heavily exposed to China also did not make it into the final draft of the German government’s strategy, which aligns with Scholz’s recent statements about placing the onus on companies rather than governments to diversify away from China. Finally, the strategy lacks a mechanism to monitor critical areas of German dependence on China—for instance, in electronics. These omissions weaken an otherwise strong policy of economic de-risking.

Germany’s new China strategy is, at its core, an economic security strategy, in which hard security issues are given only secondary consideration. This underscores the gulf between German and American priorities when it comes to China. The strategy is most explicit about security concerns when it discusses Russian-Chinese cooperation, threatening consequences if China delivers weapons to Russia and calling China’s defense of Ukraine’s sovereignty “not credible.” It also promises greater military cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners and a temporary military presence in that region. Otherwise, the strategy avoids outlining actions or a role for Germany in a geopolitical confrontation with China—for example, over Taiwan.

A BEGINNING, NOT AN END

Converging concerns about China’s ability to wield its comparative advantage in trade against its competitors have brought the United States and Europe closer together under the de-risking agenda. But significant differences persist, and Germany’s new China strategy underscores these differences. Although the strategy adopts undeniably tougher language than Berlin has used before on China, it does not represent a radical departure from the government’s previous approach. Instead, it aims to sustain German prosperity through trade with China while cautiously hedging against geopolitical risks. Germany acknowledges the reality of increasing Chinese assertiveness and seeks to “keep geopolitical aspects in mind when taking economic decisions,” the strategy states. But Berlin does not want to become a part of a confrontational “bloc” against China. As the strategy document puts it, cooperation with China remains “fundamental” to solving “many of the most pressing global challenges.”

For the United States, which sees the economic challenges posed by China as inextricably linked to the geopolitical ones, for instance in the Indo-Pacific, the new German strategy does not go far enough. But Europeans do not view China’s rise through the same prism as the United States. They continue to see it primarily as an economic challenge and less as a security threat. Europe still enjoys a third-party vantage point. From this perspective, the United States and China are embroiled in a global hegemonic rivalry, which is a different order of competition than what Europe and China are engaged in. Although they cannot escape the realities of great-power rivalry and China’s growing assertiveness, Europeans treat geopolitics as a tactical risk to avoid rather than an arena in which to engage in tandem with the United States.

Germany’s vision for a “European way” may be trying to have it both ways—reaping economic gains while underestimating hard security and geopolitical risks. If it succeeds, Berlin will prove that it is possible to cooperate and compete without escalating geopolitical tensions. Germany’s strategy might then be seen as a sensible recalibration of Europe’s approach to China, one that is attuned to European circumstances and distinct from the U.S. approach. But with a war raging in Europe and the 2024 U.S. presidential election on the horizon, just hedging against the risks of a rupture with China may not be enough. The EU and Germany may need to harness their economic clout to actively shape the geopolitical environment.

In practice, that means that Germany should aim to lead the China debate in tandem with the European Commission. To achieve this, it must avoid sending mixed signals, as it did in its May 2023 agreement to sell a nearly 25 percent stake in a Hamburg port container terminal to the Chinese company COSCO in defiance of new German regulations aimed at protecting critical infrastructure. Berlin must also avoid overestimating China’s influence over Russia and resist making major concessions to Beijing in the hope of curbing Russia’s aggression against Ukraine—a hope that may be unfounded in light of the ever-closer cooperation between Russia and China. Finally, Germany must not assume, as it did with Russia, that dependence on the European market will constrain China’s geopolitical ambitions. This would be another colossal mistake.

Germany’s new China strategy is an important step toward a more realistic assessment of Germany’s economic vulnerabilities as it becomes dangerously exposed to any disruptions caused by or emanating from China. With its focus on economic risks and only secondary consideration of hard security issues, however, it is in danger of being quickly overtaken in a rapidly evolving geopolitical environment. Even amid political infighting at home, Berlin will have to constantly reassess its exposure to potential economic coercion: what is considered an acceptable risk today may look entirely different a year hence. Without such reassessment, the country’s current approach could slow down the debate within the EU instead of advancing it. Germany’s China strategy provides a baseline, but the actual work lies ahead.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News