Abstract: Starting around February 2023, a wave of Taliban operations against Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) led some observers to herald the Taliban’s “counterterrorism” capabilities and declare ISK a defeated, or at least irrelevant, organization. Across the Durand Line, however, in July 2023, ISK perpetrated one of its deadliest attacks since its official formation in 2015, which left over 100 casualties in Bajaur, Pakistan. Since the Taliban’s return to power, ISK attacks, media output, and recruitment operations in the region have significantly expanded and diversified, which alongside its attack in Bajaur, defy claims of ISK’s defeat and irrelevance. Leveraging the authors’ years of study of ISK as well as new data, this article discusses the group’s operational strategy and persistence in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, underscoring that despite a drop in its Afghanistan-based attacks in 2023, ISK remains a potent threat. An analysis of ISK’s operations, outreach, and clashes with the Taliban indicate that the organization remains capable of strategic adaptation and is only broadening and deepening its influence in the region, posturing to become a truly regional organization. And while the Taliban have demonstrated some capacity in targeting ISK commanders, any security gains are unlikely to hold in the absence of sustained counter-ISK operations.

A devastating suicide bombing struck an election rally in Pakistan’s Bajaur district on July 30, 2023, killing over 60 and wounding well over 100 people.1 The violent assault, which targeted the religious political party Jamiat Uleme-e-Islam-Fazal led by Fazlur Rehman, bore all the trademarks of a suicide attack characteristic of Islamic State Khorasan’s (ISK’s) operations and was subsequently claimed by the group.2 The incident not only sent shockwaves throughout Pakistan—a country already plagued by political and socioeconomic turmoil—but it dispelled any notions that ISK had been neutralized by the Taliban in the early months of 2023. Instead, it illuminated an undeniable reality: ISK still retained the ability to modify its operational strategy and tactics to withstand mounting counterterrorism pressure, and orchestrate deadly cross-border attacks in pursuit of its regional ambitions. The attack also revealed glaring vulnerabilities in intelligence gathering, border security, and detection around the movement of militants in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Despite years of internationalized counterterrorism and counterinsurgency efforts in Afghanistan and Pakistan, conducted largely within the framework of the U.S.-led war on terror, political violence and terrorism continue to plague the South and Central Asian region. As demonstrated by ISK’s suicide attack in Pakistan, one of the most potent threats housed within the decentralized yet networked jihadi landscape is the persistent presence of the Islamic State’s affiliate in Afghanistan, Islamic State Khorasan. The year 2023 marks the ninth year of operation for ISK as the organization continues to navigate rivalries with actors such as the Taliban, al-Qa`ida, and the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)a while simultaneously forging deep alliances with sectarian organizations like Lashkar-e-Jhangvi. In this complex milieu of violent non-state actors, ISK has risen and faltered more than once, but has continued to adapt to changing circumstances since its official emergence in early 2015.

This article provides an overall assessment of ISK’s evolving strategy since September 2021 under the Taliban regime and situates the recent decline in its Afghanistan-based attacks within a broader strategic context that accounts for ISK’s organizational characteristics as well as regional dynamics. The article focuses on four key factors that appear to have contributed to ISK’s current trajectory and endurance, despite mounting pressure from the Taliban. First, the article discusses key shifts in ISK’s operational activities, highlighting the expanding scope of its targets as well as key geographical shifts in its areas of operation. Second, the authors discuss notable changes in the magnitude and themes of ISK’s media output and what these reveal about its growing regional ambitions. Third, ISK’s growing international nexus is examined, which has raised serious concerns about ISK’s capacity to strike across the region but also in the West. And finally, the article discusses the effectiveness of the Taliban’s approach to combat ISK since the former’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. To conduct their analysis, the authors draw upon their previous research,3 original datasets,4 primary propaganda materials, and other secondary sources.

Overall, the authors’ analysis indicates that since September 2021, ISK has grown more ambitious and aggressive in its efforts to gain notoriety and relevance across the South and Central Asian region. It has expanded the type of warfare it conducts, while also engaging in targeted assassinations of Taliban leaders. At the same time, the group’s outreach and propaganda dissemination has reached unprecedented levels in terms of form, volume, and the number of languages—clearly in an effort to recruit from both the South and Central Asian fronts. And matching its words with deeds to motivate its diverse body of fighters and supporters, and to mobilize potential recruits, in 2022, ISK also claimed cross-border attacks in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan,5 and Iran6 while targeting Chinese7 and Russian8 nationals in Afghanistan in late 2022. Some Afghanistan-watchers remain convinced that the Taliban are capable of countering ISK, and indeed, efforts undertaken by the Taliban since September 2022 have yielded some success, as discussed in this article. However, the recent decline in ISK’s attacks in Afghanistan in 2023 is likely to be an intentional strategic slowdown rather than a sustainable operational degradation. Regardless of any short-term shifts in ISK’s attack tempo, as discussed in this article, ISK remains a resilient organization, capable of adapting to changing dynamics and evolving to survive difficult circumstances. Given ISK’s recent attack in Bajaur, the crackdown on ISK in Afghanistan mostly appears to have triggered a strategic shift in ISK’s focus across the border to Pakistan’s northwestern region.

Operational Activity, September 2021 – June 2023

Expanding Nature of Warfare

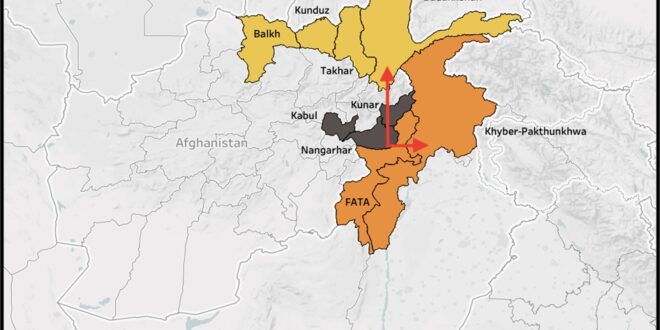

In the post-U.S. withdrawal environment, ISK has undertaken several types of attack operations that appear to be modeled on Islamic State Central’s insurgency doctrine.9 ISK currently views itself as engaged in the phase of destabilization (tawwahush),10 where it seeks to gradually implement a system of control through politico-military operations that challenge the Taliban’s declared monopoly on violence in Afghanistan. Most of these operations have multiple and often mutually reinforcing strategic logics—with the overarching goal of depicting the Taliban as a weak and incompetent governing entity. While the intensity of different types of operations has shifted over the last two years, each represents a key tool in ISK’s terrorist insurgency toolkit. Table 1 summarizes six key types of ISK’s operations (non-exhaustive), their accompanying logics, and related examples.

Table 1: ISK Attack Operations in the Post-U.S. Withdrawal Landscape

In the nearly two years since the Taliban’s takeover, ISK’s attacks increased immediately in the aftermath but then gradually declined, especially in 2023. ISK’s suicide attack on the Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul on August 26, 202124—and the intense attack campaign that followed—left many international observers concerned about the ISK threat.25 Many, including the Taliban, U.S. officials, and the former Afghan government, had deemed ISK to be a defeated organization with some remnants in early 2020. ISK’s attack on the Kabul airport and the subsequent escalation in its attacks under the Taliban’s rule alarmed regional states, as well as the international community.

ISK’s revived attack campaign following the August 2021 Kabul airport attack initially focused on Nangarhar in Afghanistan, but soon spread to 15 provinces in the ensuing 12 months through to September 2022.26 In the four months after the Taliban’s takeover, ISK claimed 119 attacks in nine provinces, 62 (52 percent) of which occurred in Nangarhar alone. From September 2021 to September 2022, ISK claimed 274 attacks, averaging about 23 attacks a month.27

As discussed further below, ISK’s rising levels of activity eventually prompted action from the Taliban, which would usher in important losses for ISK’s networks and trigger a notable decline in the group’s aggregate attack numbers toward the end of 2022. ISK-claimed attacks dropped from an average of 23 per month in the first year of Taliban rule to just four per month in the months between September 2022 and June 2023. Over this period, ISK claimed only 37 attacks in eight Afghan provinces, and the group claimed a mere 10 attacks in the first half of 2023, the majority (six) of which have been suicide attacks. The decline in ISK attacks can in part be attributed to the Taliban’s increased targeted operations against ISK’s hideouts and some of its top leaders since late 2022 (discussed further below). However, whether the lull in ISK attacks is a strategic slowdown or represents a lasting operational degradation remains uncertain. Other analysis of ISK’s activity also indicates a decline in ISK’s attacks in the second year of the Taliban’s rule, in part driven by the Taliban’s security operations.28 b However, despite the recent decline in its attacks in Afghanistan, ISK has maintained its ability to strike high-profile targets including against foreign actors on Afghanistan soil, and conduct successful suicide missions in 2023.29 Collectively, these trends indicate that ISK has intentionally pivoted to conducting fewer but high-impact attacks after exploiting the chaos that ensued in the months immediately after the Taliban’s takeover.

Another relatively recent development in ISK’s operations has been a strategic shift to targeting the citizens and diplomats of countries it considers crucial for enabling Taliban rule in Afghanistan. Notable examples include an attack on the Russian embassy in Kabul in September 2022,30 and three months later, attacks on the Pakistani31 embassy and a Kabul hotel frequented by Chinese nationals in December 2022.32 Similarly, ISK claimed cross-border attacks in Pakistan,33 Iran,34 Tajikistan,35 and Uzbekistan36 from Afghan soil. The Islamic State-claimed attack in Shiraz, Iran, in October 2022 was the first ever attack in the country attributed to ISK,37 and the suicide attack in March 2022 on a Shi`a mosque in Peshawar, Pakistan, was the group’s bloodiest attack in the northwestern Pakistan province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa since ISK’s official formation in January 2015.38 These attacks showcase the Taliban’s failures to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a terrorist staging ground, as well as their inability to account for basic state security provisions as a new de facto governing authority. ISK’s cross-border and anti-foreigner attack campaign also serves to further harden its reputation as a force seeking to ‘purify’ the country from foreigners and paint the Taliban as merely the latest puppet rulers in Afghanistan.

Geographical Expansion

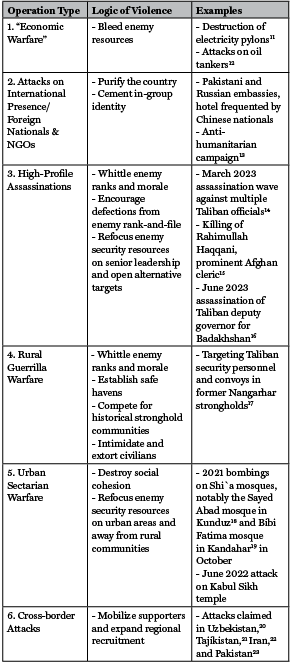

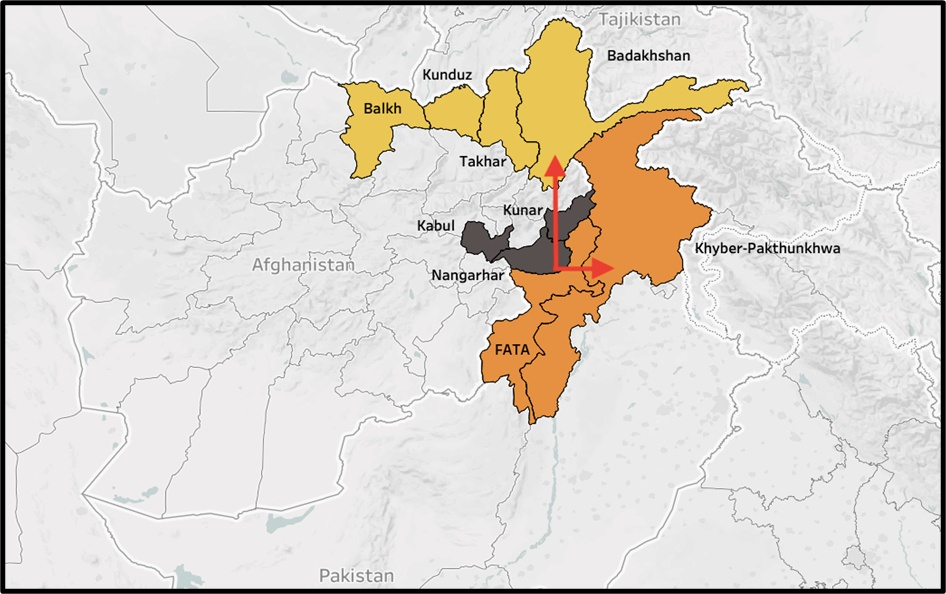

Leading up to and immediately following the Taliban takeover in 2021, ISK operations largely centered around its traditional strongholds in Nangarhar province and in and around Kabul. Virtually all of ISK’s 83 attacks in 2020 and two-thirds of its 334 attacks in 2021 occurred in these two areas.39 However, starting in 2022, ISK expanded its attack campaigns into two additional strategic regions—northern Afghanistan (Kunduz, Balkh, Takhar, and Badakhshan) and northwestern Pakistan in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province. About 27 percent of ISK’s 217 attacks in 2022 occurred in Kabul, 22 percent in KP province, and 15 percent in northern Afghanistan.

ISK’s re-expansion in KP province is particularly noteworthy. Islamic State networks in KP province, as with the rest of Pakistan, were siphoned away from ISK in May 2019 and reconsolidated into a separate branch for Pakistan, known as Islamic State Pakistan Province (ISPP).40 However, in July 2021, ISPP emir Abu Muhamud announced that Islamic State networks in KP province would be merged back into ISK.c Since then, ISK attacks have significantly increased in KP province, even as attacks have declined more recently in Afghanistan. ISK’s July 30, 2023, suicide attack in the Bajaur district of Pakistan that targeted an election underscores the group’s evolving geographic emphasis. Islamic State-claimed attacks in KP province increased from nine in 2020 to 20 in 2021, to 47 in 2022, and 12 attacks during the first six months of 2023.41 Essentially, ISK-claimed attacks in KP province jumped from 22 percent of its total attacks in 2022 to 55 percent of its total attacks in the first half of 2023.

Moreover, KP province is also important to ISK for several other reasons. It hosts a substantial portion of over two million-strong Afghan diaspora, as well as an extensive network of Afghan salafi seminaries.42 These seminaries were established in KP province dating back to the 1980s, and offered an important vehicle through which salafism spread across Afghanistan.43 Over the course of the Afghan-Soviet War and two decades of Taliban insurgency against the U.S.-led coalition, KP province also served as a key support base for jihadis of many stripes. Additionally, many of the jihadi groups with which ISK has cooperated in various forms since its official emergence in 2015 are focused in and around KP province.44 In sum, KP province has historically been a crucial hub for ISK recruitment and coordination, and these latest trends in attack data offer glaring warnings of the group’s future trajectory.

ISK’s expansion (and in some cases re-expansion, as seen in Figure 1)45 across Afghanistan’s northern provinces is also a significant development. ‘Showing up,’ competing for influence, and cementing an operational footprint in the north can help ISK recruit and garner other forms of material support from local non-Pashtun opponents of the Taliban. Many of these communities view ISK as a potent power against the Taliban, going so far as to publicly express these views in social media posts and public gatherings held after the Taliban takeover in 2021.46 The northern provinces also sit at key cross-border junctures not only for prospective foreign fighter travel (see ISK’s international nexus below), but also for humanitarian, economic, and critical infrastructure-related routes into Afghanistan from neighboring countries. Compared to other areas in ISK’s attack portfolio, the group’s operations in the northern Afghan provinces are still nascent. Nonetheless, a more active and competitive ISK insurgency along the northern borders of Afghanistan could have devastating consequences for the country and its Central Asian neighbors.

Outreach and Media Operations: Persuade, Justify, and Intimidate

Generally, the propaganda strategy and media operations of ISK consistently mirror its operational context, acting as a significant indicator of its dynamic strategy and practical tactics. And its audiences include active and potential supporters within and beyond the region, adversaries like the Taliban, regional government actors, as well as general civilian populations. Since its inception, ISK has demonstrated a sophisticated and multifaceted approach to planning and conducting media operations. Like many other prominent jihadi groups—and of course, its parent organization, Islamic State-Central—ISK has leveraged various forms of media in pursuit of its multiple goals, including propagating its ideology, providing justifications for its violent activities while vilifying opponents, casting a broad recruitment net, and of course, staying politically relevant.47 ISK’s propaganda has consisted of both official and unofficial channels. The latter has consisted of local language media offices that operated independently of Islamic State Central such as Khalid Media, al-Millat Media and Nidaa-e-Haq, and al-Qitaal (although many of these are no longer operational due to the Islamic State’s consolidation of its media outlets).48 At present, ISK’s most important (and official) media outlet is its al-Azaim Foundation, which typically publishes long-form narratives, books, and magazines but also videos on topics ranging from sharia and other religious issues to social and political matters.49

Three Waves

ISK’s propaganda narratives and media operations have generally evolved in three key waves, reflective of its changing organizational goals and strategic environment. The first wave was the period between ISK’s emergence and its first operational decline, 2015-2019, while the second was when ISK struggled to remain relevant after significant losses as the United States and Afghan Taliban negotiated for a peace deal between 2020 and mid-2021. The third (and current) wave emerged soon after the United States’ unconditional withdrawal and the subsequent takeover by the Taliban and the collapse of the Afghan government in August 2021. ISK adjusted its narratives in response to changes in its territorial dominance, organizational power, technical capabilities, and strategic objectives.

During the first wave, ISK’s outreach efforts were largely focused on its core strongholds in Nangarhar, Afghanistan. In late 2015, the Islamic State established a radio station in eastern Nangarhar called Khilafat Ghag (Voice of the Caliphate), which by the following year was providing daily broadcast services in Dari, English, and Pashto.50 Beyond religious discussions and other related topics, these broadcasts largely focused on anti-government and anti-Taliban narratives, and recruitment.51 In its nascent years, ISK used its then-held territories as a stage to depict life under its rule to boost recruitment. However, during the second wave, as ISK began to experience territorial and manpower losses, its narratives lost any specific geographic references and focused more on vilifying the Taliban by linking them to the United States in the context of the peace negotiations. Moreover, ISK also refocused its efforts, after suffering losses, on instilling fear and signaling its resolve for survival; in the months leading up to the Taliban’s takeover, ISK’s output increasingly focused on the group’s military activities, the destruction caused by its attacks, and the killing of captives.52

ISK’s third wave of outreach and media operations is arguably its most aggressive campaign, one which emerged in an environment that was expected to provide the group with a unique opportunity to reinvigorate its violent campaign following years of significant manpower and territorial losses. For the first time, ISK did not confront multilateral counterterrorism operations and instead faced a Taliban rival that was preoccupied with additional priorities beyond fighting, such as governance and law enforcement. Similarly, the Taliban’s staunch allies, most notably the TTP, refocused on their own goals of waging jihad in Pakistan,53 while other militants previously aligned with the Taliban (such as Tajik, Uzbek, and Uyghur jihadis) were left in need of a new umbrella group to pursue their own agenda. To exploit these opportunities, ISK has double-downed on the proliferation of its propaganda to disseminate its beliefs, justify its deeds, and instill fear in its opponents.

In this new phase, especially under current ISK emir Shahab al-Muhajir’s leadership, the following three developments have been the most notable.

Targeting the South and Central Asian fronts: The increase in ISK’s regional approach has been remarkable in its third wave of outreach and media operations. The organization clearly perceives the environment in a Taliban-ruled Afghanistan to be conducive to its mission of expanding its influence into South and Central Asia more broadly. This is marked by the vast number of languages that have been featured in ISK’s propaganda, which in recent years have expanded drastically to not only include the traditional releases in Arabic, Pashto, and Dari but also output in Urdu, Hindi, Malayalam, Bengali, Uzbek, Tajik, Russian, Farsi, and English.54 In September 2022, Tawhid News, a pro-ISK Uzbek-language outlet, officially announced the expansion of ISK’s jihad into Central Asia, with a focus on targeting Chinese investments and infrastructure.55 Other unofficial Islamic State-affiliated channels have consistently produced and distributed materials in South Asian languages through outlets such as Nida-e Haqq (Islamic State Pakistan Province), Al-Qitaal, and Al-Burhan (Islamic State Hind Province), respectively, while the Weekly Khilafat presents translations of Islamic State Central’s Al Naba weekly newsletters in Urdu and Hindi.56 In 2022, the group also started publishing an English-language magazine, Voice of Khorasan, in an attempt to expand its influence beyond its traditional audiences, and to perhaps appeal to younger and more educated populations who may be disillusioned or harbor grievances against local governments.

Disparaging the Taliban, and targeted criticism: Another important characteristic of ISK’s revived outreach and propaganda dissemination is its increased and sharper focus on criticizing the Taliban’s activities as Afghanistan’s governing entity, especially given the latter’s rhetorical efforts to distance itself from terrorists and attract investors. Since the U.S. withdrawal, ISK has framed the Taliban’s overtures to foreign governments as “abandonment of true jihad.”57 While anti-Taliban narratives have long pervaded ISK’s propaganda, the timing of ISK’s releases has grown more responsive to current events. For example, soon after the Taliban engaged in bilateral discussions with India in June 2022,58 ISK unleashed a series of releases criticizing the Taliban’s engagement with the Indian government, exploiting controversy surrounding Indian politicians’ statements about the Prophet Mohammad.59 Seemingly in an attempt to match its words with deeds, in June 2022, an ISK fighter targeted a Sikh temple in Kabul.60 ISK’s aspirations in India also appear heightened; in 2023, ISK claimed that the attacks conducted in Tamil Nadu and Mangalore in India in late 2022 were conducted by Islamic State-affiliated militants.61 And while Islamic State Hind Province (ISHP) has failed to gain much traction thus far, the goal to recruit Indian Muslims and incite attacks within India remains steadfast. Similarly, ISK’s critiques of the United States have become more targeted, with specific mentions of recent events and references to the Biden administration.62 In parallel, ISK’s propaganda releases have retained their focus on maligning regional government actors, referring to Pakistan as a cancerous tumor, blaming its leaders and armed forces for the current socioeconomic and political volatility in the country, while issuing direct threats to its multi-billion dollar investments with China.63 With regard to China, ISK has attempted to showcase the government’s atrocities toward the majority-Muslim Uyghur ethnic group in China’s province of Xinjiang—a concern for Chinese leaders looking to invest in Afghanistan. In a recent U.N. report, some member states noted operational and logistical cooperation between the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM, also known as Turkistan Islamic Party) and ISK, including exchange of personnel and planning of joint operations.64 In January 2023, a new pro-Taliban media group emerged, al-Mersaad, which appears to be intended to counter ISK’s messaging and discredit its operations.65

Increased audience segmentation: Related to its apparent goal of gaining regional influence and networks is ISK’s increasingly sophisticated marketing campaign. In its bid to recruit individuals who are dissatisfied with the governments of China, India, Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and various Central Asian governments, ISK carefully embeds national or ethnic themes within its overarching ideological narratives. For example, in its inaugural issue of the Voice of Khorasan, one of the articles states “numerous meetings and visits have been already made to the biggest enemies of Islam such as China, Iran and Russia. While the Taliban considers the eradication of the Uighur Muslims as an internal matter of China, the mass murders committed by the Russian, Iran regime and its proxies on the Ahlul Sunnah of Iraq and Sham is also considered something outside of their jurisdiction.”66 As an alternative, ISK offers its own platform to battle the “enemies of Islam slaughtering the Muslims.”67 But it goes further than that: Some of its propaganda directed at Tajik militants, for example, directly threatens the Tajik government, singling out its president, Emomali Rahmon.68

ISK’s extensive propaganda reveals the group’s resolute attempts to not only tarnish the Taliban’s reputation but also boost the Islamic State branch’s reach and influence across the region. So far, these propaganda efforts seem to have achieved some success in spreading ISK’s message and attracting fighters of different nationalities. The extent to which the Taliban’s nascent counter-messaging efforts via al-Mersaad can diminish the influence of ISK’s propaganda and outreach efforts remains to be seen.

International Nexus

Since the Islamic State’s global province expansion campaign first started in 2014, ISK has been one of its most successful affiliates in forging a truly international nexus. Regarding attack plots, ISK is second only to its parental namesake, the Islamic State, in Islamic State-related threats to U.S., Western, and allied interests. In addition to ISK-claimed cross-border attack plots in the immediate region against Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Iran, and Pakistan, the group has been linked to several international attack plots, including the 2020 plot against U.S. and NATO bases in Germany.69 According to reporting by The Washington Post, U.S. intelligence identified 15 ISK-linked external attack plots by February 2023, with specific efforts to target embassies, churches, business centers, and the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar.70 According to this report, ISK has been prioritizing the same ‘virtual entrepreneur’ model used by the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida in the past,71 connecting its operatives with online supporters to provide direction and instruction. Other evidence of ISK’s virtual networking include: statements by former CENTCOM Commander General Joseph Votel in 2019 that warned about ISK using its members’ social media contacts to plot attacks on U.S. targets;72 the July 2023 arrests of a number of alleged ISK-affiliated conspirators in Germany and the Netherlands, who were nationals of Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan and arrived via Ukraine;73 and a counterterrorism arrest in Istanbul earlier this year alleging a connection to ISK,74 among others.75

Furthermore, while the virtual planning model may be a short-term priority, the vacuum created by the U.S.-led withdrawal has presented ISK with unique opportunities to re-expand its training camps despite pressure from the Taliban (see below). Reported ISK training camps and strongholds now line Afghanistan’s borders not just in traditional ISK strongholds along the eastern border with Pakistan, but also along the northern borders with China, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.76 Over time, without substantial counterterrorism pressure, ISK training camps can potentially provide the critical mass for a more deadly, sustained campaign of violence not just in Afghanistan and the immediate region, but internationally as well. While ISK is focused on expanding within its immediate region for now, it is possible that ISK’s ultimate goal, as noted in March 2023 testimony by CENTCOM Commander General Michael Kurilla, is to strike on the U.S. homeland, though he noted attacks on Europe and other regions remain more likely than the United States.77

Beyond expanding ISK’s international attack-plotting capabilities, a stronger training camp infrastructure could offer ISK the necessary abilities to take in and process more foreign recruits. Since its official formation in 2015, the group has received travelers from Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, China, France, India, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, the Maldives, the Philippines, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.78 If one includes failed and foiled travelers, the list grows to include the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, and others.79 As the authors noted in a previous 2022 article, part of ISK’s resurgence strategy under current leader Sanaullah Ghafari (aka Shahab al-Muhajir) was to showcase its diverse regional fighter base in attack claims and propaganda in order to continue widening and deepening its recruitment pool.80 Analysis of more recent English-language propaganda, such as the 2022-23 issues of ISK’s Voice of Khorasan magazine, show that this strategy has continued. As ISK’s competition for an increasingly international base evolves, the role of camps and other foreign fighter processing infrastructure—as well as how ISK’s network of alliances can be leveraged to support those efforts—will become increasingly vital.

Taliban’s Counter-ISK Strategy

Since their takeover, the Taliban have engaged in various efforts to constrain ISK’s activities, while signaling to the international community that the group does not pose a serious threat. Their efforts appear to have yielded some notable successes in 2023, especially as concerns about ISK have increased internationally. In the first half of 2023, the Taliban General Directorate of Intelligence reportedly carried out around 35 raids against ISK in 11 provinces of Afghanistan.81 These efforts have resulted in the successful killing of senior ISK commanders, examples of which are provided below:

ISK’s military chief Qari Fateh was targeted in Kabul February 202382

The founding emir for Jammu and Kashmir, Abu Usman Kashmiri, was targeted in Kabul in February 202383

ISK’s senior leader and influential ideologue Abu Saad Muhammad Khurasani was targeted in the northern Balkh province in April 202384

Senior commander “Dr. Hussain” was targeted in Herat in April 202385

Deputy leader for Kabul, known as “Engineer Umar,” was killed in Kabul in May 2023.86Overall, these operations demonstrate that the Taliban have met with some degree of success in conducting intelligence-led targeting of prominent ISK figures, which are likely to have contributed to a notable decline in ISK’s attacks in Afghanistan in 2023. In particular, Qari Fateh’s and Khurasani deaths (February 2023 and April 2023, respectively) constitute significant losses for the organization, with implications for both ISK’s short-term trajectory and general morale. Khurasani was one of ISK’s most influential ideologues; he was the primary author of key publications released around the time of the group’s difficult rebuilding phase in 2020, in the lead up to ISK’s forthcoming phase of war with its main rival, the Taliban. Khurasani was also ISK’s interim emir before al-Muhajir’s appointment in May 2020.87 d

For a group that was considered to be largely defunct, the remarkable increase in ISK’s attacks in the aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal was perhaps startling and eye-opening for the Taliban—or at the very least, the Taliban were unprepared for such an onslaught of ISK violence. Prior to their takeover, the Taliban had openly claimed that ISK was a proxy or tool of the former Afghan government and U.S. forces, to be used against the Taliban. The extent to which Taliban leaders actually believed this remains unclear, but at least publicly, some of their leaders adhered to this narrative, such as the current intelligence chief, Abul Haq Wasiq, who stated in an interview in late August 2021 that ISK was no longer a threat after the U.S. withdrawal.88 ISK’s immediate rise after the Taliban’s takeover not only further undermined their quality of governance, but also served as an international embarrassment, resulting in denials by Taliban leaders about the gravity of the threat. A series of publicly claimed assassinations of the Taliban’s top-most leaders by ISK, and concerns raised by U.S. leaders about ISK’s capability to target the West,89 also likely provided the impetus for the Taliban to engage in a concerted and strategic effort to counter ISK.

Overall, while the Taliban’s recent efforts against ISK have yielded some success, leading to a decline in ISK’s attacks during the second year of the Taliban’s rule, the sustainability of these efforts remains highly uncertain given the tremendous pressure on the Taliban to govern Afghanistan. ISK’s growth into northern Afghanistan, strengthened foothold in KP province, consistent ability to execute suicide missions, and broad domestic and international outreach efforts all underscore its resilience and strategic adaptability. And if history is an indicator of ISK’s future trajectory, until counterterrorism pressure on the group is expanded and sustained, there are no guarantees of a suppressed ISK.

Conclusion

ISK’s agenda and narratives have long transcended national boundaries, given its commitment to the Islamic State’s goal of creating a caliphate, acquiring physical territories, and its deep linkages with other militant factions. In terms of opportunities to exploit in its immediate environment, ISK arguably is better positioned than ever before to evolve into a truly regional organization, one which effectively fuses transnational jihadi narratives with South Asian and Central Asian narratives, recruits from within and outside the region, collaborates with like-minded militants, and contributes to the resiliency of regional militant infrastructures. Given the current security void in the region—especially in light of the Taliban’s limited governance and counterterrorism capabilities, and resurgent sectarian and anti-government militancy in Pakistan—ISK’s evolution into a regional organization appears likely. Constraining its capabilities to conduct attacks, leverage militant networks, and propagate for influence and recruitment should be a top priority for regional governments and the international community.

ISK’s increasingly networked and regional nature and its ability to recover from losses in the absence of sustained counterterrorism pressure necessitate a coordinated regional security approach. Cooperation is especially important for effective use of intelligence to disrupt ISK’s plots and also to constrain its members from cross-border movements. Regional governments may seek to provide limited counterterrorism capacity-building support to the Taliban to allow them to target ISK’s leadership and infrastructure with more precision, but the second- and third-order effects of such support must be carefully weighed. In light of ISK’s ability to generate and disseminate an immense volume of propaganda targeting different populations in several regional languages, government actors need to work closely with the technology sector to support deplatforming efforts, especially in non-English language propaganda where content moderation efforts are still wanting. Finally, governments need to work with civil society actors to address the underlying grievances that ISK seeks to exploit, and which make civilians vulnerable to false narratives and conspiracy theories, such as poor human security, repression, sectarian discrimination, and intolerance toward minorities.

In the absence of a comprehensive policy response, unfortunately, ISK is likely to continue to reverse any limited short-term counterterrorism successes, as it has done so in the past, and continue to leverage existing security gaps to revive and expand.

Substantive Notes

[a] Since the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul, the once somewhat covert rift between ISK and the TTP has deepened, as evident in their media clashes. The TTP’s denouncement of ISK’s assault in Bajaur framed the attackers as “Khawarij” and agents of Pakistani intelligence. In retaliation, ISK depicted the TTP, similar to the Afghan Taliban, as nationalists and alleged collaborators with state actors. Despite this, the TTP, mirroring the Afghan Taliban’s strategy, has been downplaying the threat posed by ISK and avoid mentioning it directly, and instead, has been insinuating that their attacks are schemes of Pakistani intelligence, (especially evident in their reactions to the Bajaur attack). Meanwhile, rumors suggest the TTP assisted the Afghan Taliban in curbing ISK’s influence along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border post the Taliban’s ascendancy in Kabul. These insights are based on various discussions and interviews with local sources undertaken by author Abdul Sayed during the years 2022 and 2023. See also Amira Jadoon with Andrew Mines, The Islamic State in Afghanistan and Pakistan: Strategic Alliances and Rivalries (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2023).

Citations

[1] Christina Goldbaum, “ISIS Affiliate Claims Responsibility for Deadly Attack at Rally in Pakistan,” New York Times, July 31, 2023.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News