In his memoirs, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu recalls a significant event from 2013 when then-US Secretary of State John Kerry proposed a secret visit to Afghanistan to see US-trained forces:

“Bibi, I want to arrange a clandestine visit for you to Afghanistan. You’ll see with your own eyes what a great job we did there to prepare the Afghan army to take over the country once we leave.”

Eight years later, the result of this “great job” was an embarrassing spectacle, a diplomatic humiliation, and a national security catastrophe.

From here on out, every August bears witness to the anniversary of the “most humiliating reverse for US and British foreign policy in recent memory,” as The Guardian put it earlier this year.

Costly Afghanistan exit

On 30 August, 2021, the final US soldier left Afghanistan, effectively ending a two-decade-long war and occupation. But the withdrawal didn’t play out as Washington intended, leading instead to a situation that western media and even US politicians characterized as “catastrophic and humiliating.”

In February 2022, a report was issued by the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations entitled “Left Behind: A Brief Assessment of the Biden Administration’s Strategic Failures During the Withdrawal from Afghanistan.”

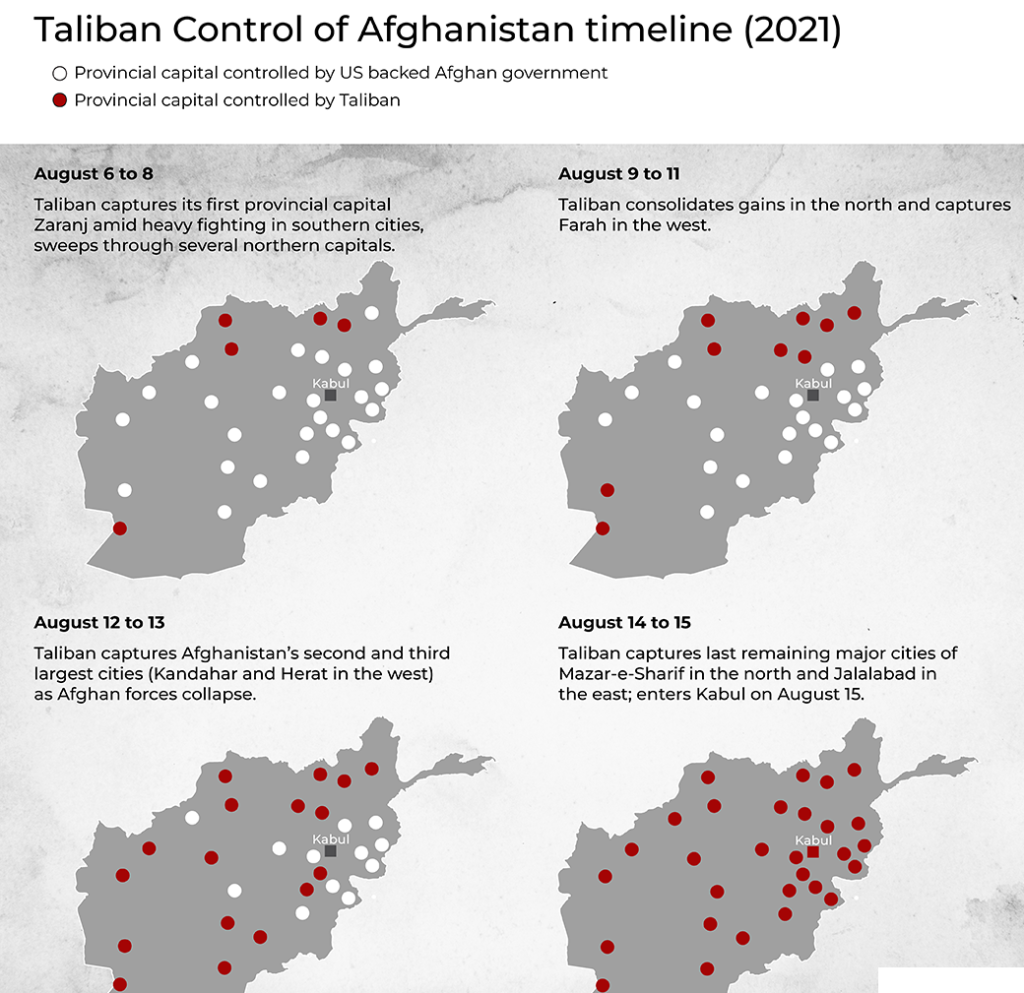

The report focuses on the Biden administration’s failure to anticipate the Taliban’s rapid takeover of Afghanistan, which was established promptly after US troops left. It states that the Biden administration ignored several intelligence warnings and decided to abandon the Bagram Air Base despite reports that this could lead to the Taliban seizing control of the capital, Kabul.

The report further reveals that the White House ignored the State Department’s opposition to the withdrawal, failed to plan an evacuation until it was too late, and, in the process, abandoned tens of thousands of Afghan partners.

Then-Republican House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy referred to the withdrawal as a “tragedy” and “the worst foreign policy disaster in a generation” in a letter addressed to House Republicans. Further emphasizing the gravity of the situation, House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Michael McCaul deemed the withdrawal disastrous and called for accountability among US officials involved in the process.

These sentiments were mirrored by the US public, as various polls revealed. A 2021 Pew Research Center poll showed that 69 percent of respondents believed that the US had failed to achieve its goals in Afghanistan.

Similarly, a CBS News poll revealed that 74 percent of respondents felt that the US had poorly executed the troop withdrawal. Even among US veterans, a significant number expressed feelings of betrayal (73 percent) and offense (67 percent), with a majority acknowledging challenges in coming to terms with the war’s conclusion. A striking 70 percent of veterans believed that the US had not departed Afghanistan with honor.

A blow to western soft power

During the tenure of former US President Barack Obama, the concept of “smart power” gained traction in US foreign policy discourse. This approach, as defined by Joseph Nye, a former government official and a former dean at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, stipulates that the president must be able to combine hard power, characterized by coercion, and what Nye calls “soft” power, which relies instead on attraction. This marked a shift from the hard power-centric policy of former President George W. Bush.

However, the optics associated with the US withdrawal undermined Washington’s endeavors to portray itself as a champion of human rights and a superpower.

Disturbing images, such as Afghans desperately clinging to an American plane leaving Kabul only to fall to horrible deaths, as well as attempts to secure the exit of Afghan children, portrayed distressing scenes reminiscent of the fall of Saigon at the close of the Vietnam War. Countless visual records of Americans prioritizing their own safety over Afghans sharply contradicted the image the US seeks to project globally.

In a study recently published in the academic journal Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, a novel concept called “passive viewing” is introduced, which stresses the importance of monitoring the decline of a country’s soft power and the subsequent consequences on its global standing.

The author of the study posits that “passive viewing” can be assessed through three key indicators: the state’s systems of governance (indicative of internal state affairs), the perception of the state by its residents (reflecting their outlook), and the objective perception of the state by external entities.

By observing these indicators, it becomes possible to gauge the deterioration of a country’s reputation, which correlates with the diminishing of its soft power. The study concludes that a decline in soft power is associated with an elevated security threat to the country: A weakened soft power position encourages challengers, thereby posing a security risk.

Based on this proposition, it can be argued that the US’ global reputation is declining as a result of a series of decisions it has adopted, including the manner of its withdrawal from Afghanistan. This phenomenon potentially explains the growing assertiveness of Washington’s allies – such as those in the Persian Gulf – leading them to resist certain demands that align with US interests but conflict with their own.

Abandoning allies and losing trust

While US forces rushed to withdraw from Afghanistan, abandoning their Afghan partners to a likely Taliban takeover, planes were used to transport animals such as dogs and cats out of the country. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s report revealed that as many as 9,000 Americans were left in Afghanistan during the ill-fated retreat. The optics worsened as Eric Prince, the founder of Blackwater, a notorious US private military company, offered individuals the opportunity to leave Afghanistan for a fee of $6,500 per person.

Even major US allies in Europe responded with a mix of distrust and feelings of betrayal. European Council President Charles Michel voiced concerns that “The chaotic withdrawal in Afghanistan forces us to accelerate honest thinking about European defense.”

The sentiment was also expressed by the President of the Czech Republic, Milos Zeman, who labeled the troop withdrawal as a “betrayal.” Similarly, Josep Borrell, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of the EU, emphasized the need to reduce Europe’s reliance on the US and pursue more independent decision-making following the Afghanistan debacle.

Although these opinions haven’t translated into significant actions in the two years since the US troop exit, they expose the shaky dynamics of the relationships Washington has with its closest allies.

From the perspective of Israel, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan raised alarm bells. A 2022 analysis by Yoram Schwarzer and Eldad Shavit from Tel Aviv University’s Institute for National Security Studies concluded that the US departure from Afghanistan was being interpreted – in and out of Israel – as a willingness by Washington to abandon its allies, potentially setting a precedent for other regions.

Lessons unlearned from Afghanistan

Two years on, what deserves our attention is not the disastrous withdrawal itself, as the west describes it, but an addiction to dependence on Washington and not learning from past events. After the war in Ukraine, it became clear that a noteworthy number of Washington’s allies around the world, including its allies in West Asia, began to be treated for this addiction, which was reflected in their refusal to comply with Western trends against Russia. Many of Washington’s West Asian allies have since recognized the necessity of diversifying their international relations to prevent the risk of abandonment by the US.

One of the key motivations behind the US withdrawal from Afghanistan was to allocate resources toward other priorities, particularly the regions surrounding Russia and China. The US is, therefore, repositioning itself in West Asia to optimally address emerging challenges and conflict with Moscow and Beijing. Presently, much of the US’s focus is directed at the conflict in Ukraine, where it is evident that Kiev hasn’t heeded the lessons from the Afghan situation.

But West Asia has clearly moved on from tying its fortunes entirely to Washington’s whims. Whether it was the US abandonment of its Afghan allies, its refusal to repel Yemeni missile attacks on Saudi and Emirati territory, or its unilateral seizure of hundreds of billions in Russian assets in western financial institutions, the region’s pro-American leaders are no longer placing all their bets on Washington.

Conversely, as the US fixates more keenly on thwarting Russian and Chinese influence, West Asian states are reaching out in greater numbers to the power centers in Moscow and Beijing. Tellingly, two staunch US allies, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, last week joined the BRICS – the Global South institution that is challenging dollar dominance today. The two Persian Gulf states were joined by Iran, a major US adversary, and bets are on that the BRICS will collectively work to eliminate the petrodollar, a huge threat to US financial dominance around the world.

Subsequent to the Ukrainian conflict, it has become apparent that a substantial portion of Washington’s global allies, including those in West Asia, are putting state sovereignty first through their defiance of western diktats against forging closer ties with China and Russia.

As the anniversary of the withdrawal from Afghanistan approaches, Asian hegemons in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and New Delhi, who still retain close and collaborative relations with Washington, will not doubt be reminded of how frail and unreliable US power projection has become.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News