Introduction

The war in Ukraine has fundamentally changed the Russian-Iranian relationship. The cooperation between the two countries has reached unprecedented levels, evident in the use of Iranian drones by Russia in Ukraine. The two countries have increased their efforts to jointly resist Western sanctions and political isolation. Iran also continues to expand its nuclear programme at alarming levels – with no opposition from Moscow.

These realities present new, direct security threats to European governments. Firstly, the strengthened partnership may enable Russia to prolong the war and increase the destruction in Ukraine. Secondly, together they can alter the balance of power in the Middle East through Russian support of Iran’s nuclear ambitions, arms transfers to Iran, and threats of military escalation in Syria. Thirdly, they might undermine Western influence in institutions of global governance.

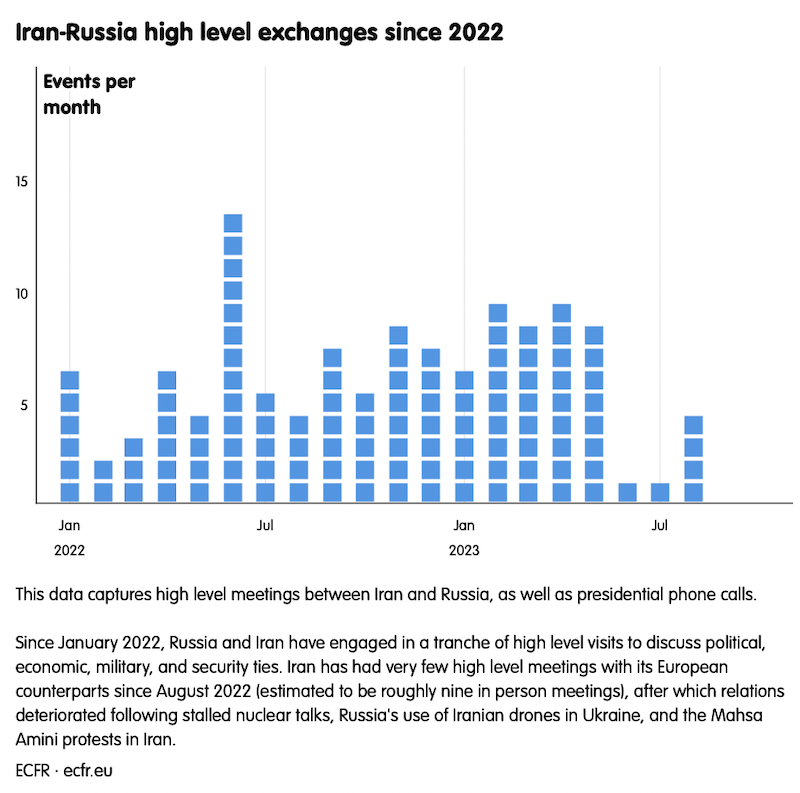

The Ukraine conflict only accelerated the steadily deepening ties between Iran and Russia. But, over the past decade, Moscow remained mindful not to antagonise the West and Israel through its relations with Tehran. Now, in the wake of the Ukraine war and the consequent breakdown of relations between Russia and the West, Iran has emerged as one of Moscow’s most steadfast allies. Several weeks before Russia launched its war, Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, discussed finalising a long-awaited 20-year cooperation agreement to expand relations on all fronts.

Russia now finds itself reliant on Iran in ways that were unimaginable prior to February 2022. Tehran’s military contribution to Russia’s war effort has made an enormous difference to Russia’s ability to persevere in a difficult conflict. Iran, once a secondary player, is now one of Russia’s most significant collaborators in the war in Ukraine.

Russian eagerness to cooperate with Iran coincides with a notable tilt in Iranian domestic politics away from seeking normalisation with the West. Iran has experienced a string of disappointments in its relations with the West. These include the failed 2015 nuclear deal, known as the “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action” (JCPOA); the inability of European countries to continue economic relations with Iran following the Trump administration’s 2018 withdrawal from the deal; and the Biden administration’s initial hesitancy to quickly restore the JCPOA. This deadlock worsened following US intelligence revelations in July 2022 that Iran was planning to send combat drones to Russia, and the brutal nationwide crackdown on Iranian protestors that began in September 2022.

A significant factor pushing Iran to support Russia’s war in Ukraine is the rise of hardliners and the deep state in monopolising decision-making. This power balance dynamic directly influenced Iran’s decision to support Russia in the conflict. As one Iranian expert describes, “the West repeatedly disappointed [the more moderate] faction by betraying their deals and giving them nothing. Meanwhile, Russia has nurtured and strengthened the hand of the hardliners now in power. It has offered and delivered economic gains, military upgrades, and security assistance to maintain their position.”[1] Russia’s and Iran’s anti-Western stance has been part of what holds their relationship together for some time. As both countries faced downturns in their relations with the West, they found more common cause to contest the US-led international system and to push for their mutual vision of a multipolar world order.

This paper explains how Russia and Iran have sought to upgrade their partnership through greater diplomatic support for pushing back on Western hegemony, mutual provision of key weapons systems, and sharing of expertise on evading sanctions.

While European countries will be unable to halt these advances in the Russia-Iran relationship completely, the paper recommends how to reduce the damage to European security through a calibrated mix of coercive pressure and diplomatic tools. On the former, European governments should continually review and enhance their restrictive economic measures targeting Iranian drone and missile production. These measures may slowly degrade Iran’s supply lines while Western governments bolster Ukrainian defences. European countries should also work with the United States and other allied nations to deepen their intelligence on Iran-Russia arms transfers and to publicise the results where appropriate.

Previously, the West managed to negotiate with Moscow to isolate Tehran, but this is clearly not possible now given Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. The West may be able to slow down the Iranian partnership with Russia through a transactional deal with Tehran. Measures that de-escalate tensions between the West and Iran can create diplomatic openings to drive a wedge between Russia and Iran.

The essence of these efforts is that they would require Iran to halt or wind down actions that gravely harm European interests. This could include reducing its arms transfers to Russia, rolling back its nuclear activities, and ceasing attacks against Western interests in the Middle East. In exchange, the West should offer Iran relief from various economic sanctions imposed by the US and European Union.

Iran’s geopolitical ambitions remain paramount. Yet, economic needs continue to shape Tehran’s foreign policy and debate. Public figures and media associated with the reformist faction – which, while marginalised, offers a way to gauge public dissent inside Iran – openly criticise both Russia and Iranian military assistance in the Ukraine war. Some of these figures condemn the decision to provide drones to Russia because it cost Iran its chance to improve relations with the West and ease economic sanctions by restoring the JCPOA. Others worry that Russia created a “trap for Iran”. Moreover, a former Iranian official warns that Iran is being dragged into the “quagmire” in Ukraine, adding that “the Chinese were smart enough not to get trapped.

Even after Raisi’s hardline government took office in 2021, Iran negotiated – albeit stubbornly – with the West over nuclear issues and detainee releases. Despite Tehran’s clear tilt towards Moscow and Beijing, they have been unable or unwilling to deliver on Iran’s critical economic needs. European and US sanctions relief could provide Iran with breathing room at a time when it desperately needs to improve economic conditions. As such, Iran’s leaders could see an advantage in reducing their support for Russia’s war in exchange for the immediate economic relief that only Western countries can provide.

This will not equate to a major transformation of Iranian behaviour. Diplomacy also carries risks for European governments. Those risks include legitimising an increasingly unpopular Iranian ruling elite only a year after they brutally suppressed nationwide protests. An effort to reduce tensions with Iran does not preclude continued Western efforts to mobilise international pressure regarding Iran’s domestic human rights conditions. By contrast, a deepening Russia-Iran partnership will only strengthen the hold of the hardline actors inside Iran who are primarily responsible for human rights violations. Unfortunately, the Russian-Iranian relationship is emblematic of the emergent new global order, in which European countries will have to engage in unsavoury trade-offs to counter geopolitical blocs seeking to weaken the West.

Deep state military and security partnerships

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the military-security relationship between Moscow and Tehran was primarily characterised by a patron-client dynamic, with Russia as the patron providing Iran with military equipment. Iran’s provision of drone technology to Russia, which has played an important role in Ukraine, has reshaped this dynamic – so much so that US officials warn that Moscow and Tehran are now developing a “full-fledged defense partnership”.

The Iranian-Russian military partnership had already intensified after the two countries began active cooperation in the Syrian civil war. The military contacts established in Syria likely facilitated Russia and Iran to more swiftly engage in the transfer of drones and munitions that have been used inside Ukraine. To transfer this military equipment, Iran and Russia are believed to primarily use cargo planes and ships to cross the Caspian sea.

These developments are not only advancing Russia’s capabilities in Ukraine, but they also have the potential to provide Iran with a stronger military hand in the Middle East.

Iranian military assistance to Russia

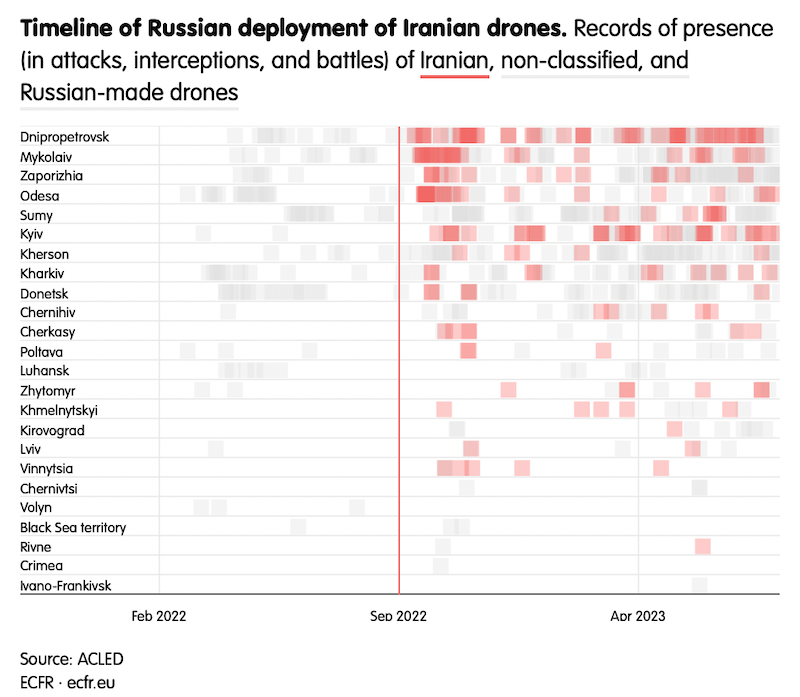

The most threatening aspect of the recent Russian-Iranian relationship for Europe is the use of Iranian combat drones by Russia to target critical infrastructure (including power grids and radar stations). Russia has deployed swarms of Iranian-made drones in regular attacks inside Ukraine since September 2022. The Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, alleges that Russia has sought to acquire at least 2,400 drones from Iran.

Following repeated denials, Iranian authorities eventually admitted in November 2022 that small numbers of drones had been delivered to Russia before the Ukraine conflict began. Iranian officials continue to deny that Iran provides military assistance to Russia’s war in Ukraine. However, some hardline media pundits in Iran admit and even celebrateIranian drones being used in Ukraine.

US officials claim the first batch of Iranian drones was delivered to Russia in August 2022. These included the Iranian Shahed-131/136 series, which are “Kamikaze drones” intended to explode on contact; and the more sophisticated Mohajer-6, used for intelligence gathering and firing precision-guided munitions. The Washington Post reports that, according to intelligence provided by Ukraine, Russia “attacked Ukraine with more than 600 of the self-detonating [Iranian] Shahed-136 drones” between May and July 2023. By early August 2023, Zelensky claimed Russia had used over 1,900 Iranian-made drones inside Ukraine.

Russia faces major challenges in manufacturing enough missiles to sustain its ongoing offensive in Ukraine. Iranian drones help fill the gaps. Iran’s investment in low-cost drones began during the 1980s war with Iraq. It is in part driven by the need to compensate for its degraded air force, which has been unable to maintain its fleet of mainly US-manufactured aircraft due to sanctions. Iran’s drone programme has been very successful, and Russia has been able to observe the showcasing of Iran’s drone capabilities over the past four decades. The US and Saudi Arabia allege these demonstrations included sophisticated drone attacks on Saudi oil infrastructure in 2019.

A report from the UK-based Conflict Armament Research (CAR) into Iranian drones downed by Ukraine shows that these systems rely heavily on components manufactured by US, European, and Asian companies in 2020-2021. These components are used for both military and commercial purposes and are thus widely available. The same report concludes that Iran and Russia were stockpiling drone components prior to the start of the Ukraine war.

CAR has also reported finding Chinese parts produced in 2023 in Iranian drones used in Ukraine, and in another report the organisation found that Russia has started producing its own version of the Shahed-136. This new capacity reflects Iran’s ability to help Russia bypass the Western sanctions imposed since 2022. As one expert puts it “outsourcing smuggling and diversification efforts to Iran makes it easier for Russia to obtain key components [for its] chemical and industrial pre-products in larger quantities,” and will make it harder for Western intelligence to track.[2]

According to Ukrainian forces, the country has shot down the majorityof the slow-moving Iranian systems. Nevertheless, these drones provide Russia with three key advantages:

Firstly, they are a cheap way for Russian forces to jam Ukraine’s air defence systems before cruise missiles are launched.[3]

Secondly, downing Iranian drones comes with a high price tag for Ukraine. On average, the drones are estimated to cost $20,000 to manufacture, while the cost of shooting them down ranges between $140,000-$500,000. As Zelensky suggests, deployment of these drones in civilian areas can over time give an advantage to Russia in depleting Ukrainian resources and civilian morale.

Thirdly, Iranian-designed drones could cause greater damage if Russia and Iran cooperate on improving them. In February, the Wall Street Journal reported claims by unnamed officials that the two countries are in talks to jointly build a factory in Russia’s Tatarstan region to manufacture more sophisticated Iranian-designed drones. US intelligence predicts this factory could be operational by early 2024, and states it would be able to produce “orders of magnitude higher” quantities of drones than previous Iranian deliveries to Russia.

The arms transfers from Iran to Russia may go beyond drones. In April, sourcing unnamed Middle Eastern officials, the Wall Street Journalreported that Iran had sent over 300,000 artillery shells and a million rounds of ammunition to Russia. In December, the US also alleged that Iran is considering providing Russia with hundreds of short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs). Russia is believed to have depleted its ballistic missile inventory, and although the Iranian weapons are less accurate than their Russian counterparts, they could be an important asset. According to Gustav Gressel of the European Council on Foreign Relations, the potential use of these missiles presents a greater challenge than drones to the Ukrainian forces as it would be harder to intercept them.[4]

There is currently no evidence that Iran has transferred missiles to Russia. One reason could be that Iran has acknowledged the risks of the Western response are not worth the likely benefits offered by Russia for such a deal. One former Iranian official explains that Iran is unlikely to provide Russia with missiles, as this would drastically increase the perceived threat to Europe.[5] European officials say they have made clear to Iran that the transfer of SRBMs would be a “red line” and trigger a harsh response from the West.[6]

Another reason Iran may have held back on the SBRMs deal with Russia is out of practical necessity. One former European military official explains that Iran may need to stockpile its own resources as a deterrent against the West and Israel during current military tensions.[7] Talks between Russia and Iran over this deal could also have stalled because they cannot agree on the terms. Overall, Iran’s calculations on transferring SBRMs to Russia are likely to be influenced by both the price that Moscow is willing to offer, and Iran’s relations with the West.

In February 2023, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) issued a veiled threat to Europe over missiles, noting that Iran had so far limited the range of its missiles “out of respect for Europe”. This rhetoric may indicate that Iran could also become more open to transferring missiles to Russia if relations with Europe considerably worsen. As one senior Iranian expert noted, “if Iran is placed under more pressure by the West, they may use [SRBMs] as a chip to impose greater pressure on the West in response.”[8]

Besides arms transfers, another Western concern is the possibility of Iran boosting Russian manpower. US intelligence reportedlydetermined that IRGC military trainers were sent to Russian bases in Crimea in 2022 to overcome operational problems with Iranian-made drones. Russia may look to recruit forces from Iranian-backed non-state groups active in the Middle East. In March 2022, Russia claimed around 16,000 volunteers from the Middle East were prepared to fight in Ukraine. However, in light of the Wagner mutiny, it is unclear whether this will materialise.

Russian military assistance to Iran

European officials worry that Moscow will get Iran to provide greater military backing to the war in Ukraine than it was previously prepared to offer in exchange for military technology and security assistance.[9] Western governments are also concerned that Russia’s willingness to transfer more sophisticated arms to Iran would provide Tehran with more military capacity to advance its regional agenda, particularly against Israel and Saudi Arabia.

US officials warn that Russia is already engaged in an extraordinary level of defence cooperation with Iran, extending to electronics, air defence, attack helicopters, and radars. In September, Iranian state media ISNA announced Iran’s air force received Russian-made Yak-130 combat trainer aircraft that can help pilots fly more advanced fighter jets. This cooperation includes the potential transfer of Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets that could significantly advance the performance of Iran’s military arsenal. The US has also raised concerns about Russia providing training to Iranian pilots.

The timing and content of the Su-35 deliveries remain uncertain given the challenges surrounding Russia’s production of defence equipment.[10] In March, the Iranian IRIB news outlet reported that a purchase deal had been “finalised”. In July, Iran’s defence minister suggested that the deal had collapsed, commenting that Iran had home-grown capacity to meet its needs. Another Iranian defence official subsequently downplayed Iran’s need to purchase the Russian jets.

According to one defence expert, this could indicate that Russia and Iran have so far been unable to agree on the terms and conditions over the fighter jets, or that there is a technical delay in the delivery of the planes due to constraints on Russian production.[11] According to a Russian defence expert, however, the deal is too important to both sides for it to ultimately fall through.[12] Another Russian defence expert suggested that the Su-35 deal was a way for Russia to demonstrate its goodwill to Iran, noting that “there’s a price to pay for everything. At a certain stage, Russia needed to show it was a loyal partner.”[13]

It is possible that Su-35 fighter jets could be delivered in the future as payment for Iranian drones or more advanced weapons (such as SRBMs). There is no public account from Western, Russian, or Iranian officials on what Russia already paid for the drones that Iran delivered. But, according to one Iranian security expert, Russia gave Iran $6 billion in cash for drones.[14] Sky News reported in November 2022 that in exchange for Iranian drones, Russian military aircraft arrived in Tehran in August 2022, carrying a significant amount of cash, a British NLAW anti-tank missile, a US Javelin anti-tank missile, and a US Stinger anti-aircraft missile. Iran could use the know-how obtained from such Western equipment to advance its own indigenous arms production.

According to documents obtained by the Washington Post, Iran is to receive over $1 billion for the joint drone factory production in Tartarstan “to be paid for in dollars or gold” due to the volatility of the Russian rouble.

Another area closely watched in Western and Middle Eastern capitals is whether Russia provides Iran with its S-400 air defence system and supports Iran’s missile production. Advanced air-defence systems from Russia could enhance Iran’s ability to defend against potential attacks on its nuclear infrastructure and other strategic facilities. As one expert notes, Iranian leaders are also less interested in the S-400s as an end product than they are in receiving the technology to develop indigenous missile systems.[15]

Russian cyber technology is also a capacity that Iran wants to acquire, as highlighted in the November 2020 agreement between the countries on information security. Cooperation in cyber and surveillance helps both governments counter their perceived domestic threats, particularly their fear of Western involvement in internal protests and upheavals. In March, the Wall Street Journal reported that Moscow supplied Tehran with a significant upgrade to its digital capabilities by offering powerful surveillance software with the potential to enable disruptive cyberattacks. US officials believe Iran is using Russian software to suppress protests, including by slowing down internet traffic and communications, and facilitating the identification and apprehension of demonstrators.[16]

In 2021, Russia provided Iran with the Kanopus-V satellite, which was of significance since it equipped Iran with unparalleled espionage capabilities. Russia’s deployment of another Russian-made Iranian satellite into orbit in August 2022 underscored not only their growing cooperation in space but also in intelligence. This project has faced opposition from Israel and the US due to concerns that it could advance Iran’s missile guidance systems.

Finally, Iran is gaining battlefield knowledge from Russia’s war in Ukraine. As one expert put it, Russia can provide Iran with sensitive information regarding Ukrainian air defence systems and the effectiveness of Western military equipment.[17] In the early 2000s, Iran spent extensive resources learning from Russian operations in Chechnya and from US military operations in the 2003 Iraq invasion. This, according to one expert, significantly informed “Iranian operational doctrine”, and a similar model of learning in Ukraine could prove valuable.[18]

The uncertain future of military ties

Despite the increased enthusiasm in both Iran and Russia to deepen military ties, several factors will restrain how far they are likely to go. Firstly, as one Iranian expert explains, while the two sides have mostly overcome the political hurdles, “the problems are technical: Iran may not have ability to pay Russia, and Russia may not be able to produce the equipment Iran needs on agreed timelines.”[19] These difficulties could become major obstacles. Russia is struggling to sustain its production lines to wage war in Ukraine and is unlikely to prioritise the needs of Iran. The long delay in the delivery of Russian fighter jets to Iran illustrates this dilemma.

As another expert notes, Iran wants to avoid “repeating the experience of the past when deals with Russia [were] not workable.”[20] For example, in 2007, Iran agreed to purchase the Russian S-300 surface-to-air missile system, and even paid for it, but then faced an uphill struggle to actually receive the system. The Russian government dragged its feet for years and then, as part of the international pressure against Iran’s illicit nuclear activities, in 2010 banned the delivery of S-300s and other weapons to Iran. This in turn prompted Iran to sue Russia. Moscow finally delivered the system in 2016.

This experience, combined with the recent uncertainties over the Su-35s, may determine how far Iran is willing to go in transferring arms to Moscow if those transfers antagonise the West. SRBMs stand out as an important example of where this logic might apply. On the other hand, if Russia does go ahead with the delivery of fighter jets, and the provision of more satellite systems to Iran, this will likely influence Iranian attitudes towards supplying Russia with more lethal weapons for use in Ukraine.

Secondly, there are strategic restraints on greater military cooperation on both sides. Concerns linger in Moscow that domestic political trends in Iran could eventually favour an Iranian tilt to the West.[21] In this scenario, Moscow would not want Tehran to possess valuable Russian military technology and equipment. Russia is also likely hesitant to formalise a military alliance with Iran because this would restrict its freedom with other important states, such as Israel and Saudi Arabia, which remain deeply suspicious of Russian-Iranian military ties.

Russia’s ties with Iran’s rivals in the Middle East have often led to clashes with Tehran. For example, in July, Russia issued a joint statement with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) directly challenging Iran’s territorial control over three Gulf islands. (China made a similar statement in 2022.) This led to a public backlash by Iran’s government that included the Iranian foreign ministry formally summoning the Russian ambassador to Iran to explain. A group of former senior Iranian diplomats called for the government to rebalance its relations between the West and Russia, describing Moscow’s move as “wholly unacceptable”. Iran’s former foreign minister, Javad Zarif, a longtime proponent of balancing East and West in foreign relations, warned that Tehran is misguided in its belief that Moscow can be an ally. Even Iranian political figures and media outlets associated with conservative factions openly criticised Russia.

Iran has also not entirely given up on the West. As one expert on Iran flags, “Tehran is also influenced by the strong response from Europe and the United States over its military support to Russia”, and it does not want to sacrifice its options for sanctions relief with the West by putting all its eggs in Russia’s basket.[22] In July, the director of the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency, William Burns, noted that the “Iranian leadership has hesitated about supplying ballistic missiles to the Russians … partly because they’re concerned not just about our reaction but about European reaction as well.”

Overall, key Iranian decision-makers believe that the Ukraine war has opened new opportunities for Iran that must be seized. As one Iranian expert explains, the deep state views the geopolitical shifts created by the Ukraine war as a “divine gift to Iran”.[23] According to this perspective, whether Russia wins or not, Iran can profit; the same way as “Europe claimed it sought an end to the Yemen conflict but had no problem selling arms to Saudi Arabia to support the bombing.” [24] By demonstrating, for example, the advanced capabilities of its drones in Ukraine, Iran is effectively getting free advertising for its military technology that may influence potential buyers in Africa and South America.

As a former senior Iranian official predicts “the longer the [Ukraine] war prolongs, and Western sanctions relief is off the table [for Iran], the more concessions Iran will offer Russia to ensure it does not categorically lose in the Ukraine war.”[25]

Forced Economic Marriage

Russia is now virtually on a par with Iran as one of the most heavily sanctioned countries in the world. Iran has navigated sanctions for over four decades and has developed almost a blueprint for Russian officials on how to evade them. In the aftermath of Ukraine-related sanctions, according to one Russian economic expert, there has been “a lot of serious work” to improve economic ties between Russia and Iran, which had always been “a weak point” in the relationship.[26] Their economic ties suffer from a lack of transport infrastructure, the impact of Western sanctions on their financial links, and competition in the energy sector. Iran and Russia have attempted to overcome these hurdles by increasing cooperation in four key areas.

Boosting bilateral trade

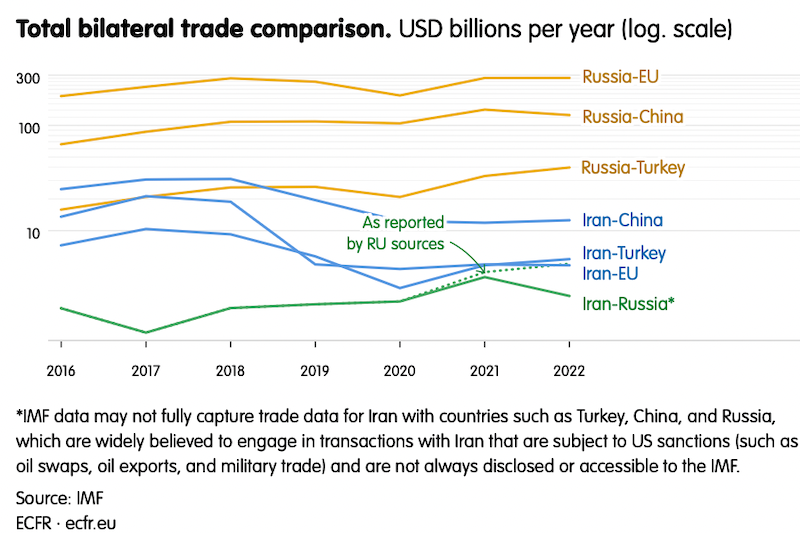

Since February 2022, according to one Russian expert, Moscow’s focus on boosting trade ties with Iran has been “one of the areas where there is a transformation” in Russian thinking.[27] Russian officials assert that in 2022 the country increased bilateral trade with Iran by 20 per cent compared to the previous year, reaching $5 billion. Data from the IMF shows total trade during this period at $2.4 billion, but this total may miss some trade, including oil swap deals and military trade, details of which are not disclosed by Russia and Iran. According to Iranian officials, Russia has become the biggest foreign investor in Iran, having invested $2.76 billion in the latest Iranian fiscal year (March 2022-March 2023). One business leader inside Iran relates that “Iran has become a bazaar for the Russians, for everything from tyres to drones.”[28]

The biggest portion of Russian-Iranian trade has traditionally consisted of foodstuffs that are exempt from US sanctions. The question now is whether, following new Western sanctions on Russia, the trade picture will significantly change in the coming years. Russia and Iran have signed several new agreements to offer each other much-needed alternatives to Western imports. Auto parts, gas turbines, and servicing Russian aircraft are key areas in which Iran is supporting Russia’s domestic needs.

Russian and Iranian officials claim they aim to boost annual bilateral trade to $40 billion. This is a very ambitious target given the low volume of existing trade between the two countries, which falls far short of Russian trade with China, Turkey, and the EU.

Following Western sanctions, Russia has prioritised China as its key partner to make the switch from European supplies. This, according to one economic expert, is a “natural shift … Iran’s trade flows made a similar shift towards China to meet its post-2010 sanctions needs.”[29] This development illustrates that despite the political appetite for more trade, Russia and Iran cannot yet comprehensively compensate one another for the Western market from which they have been cut off.

Banking and de-dollarisation

Western sanctions severely restrict the ability of Iran and Russia to access global financial and banking platforms. Russian and Iranian officials acknowledge that this has undermined their ability to boost trade and investment. Since the wave of sanctions following the Ukraine war, Russia has increased its efforts to overcome these restrictions by cooperating with Iran on strengthening alternative banking avenues and pressing for the de-dollarisation of international trade.

Moscow began a serious push for de-dollarisation following Western sanctions imposed in response to its 2014 annexation of Crimea. To safeguard against the possibility of being disconnected from the global financial transfer system operated by Belgium-based SWIFT, Russia’s Central Bank established its own financial messaging system known as the SPFS. Since 2016, Russia has made progress in bypassing the dollar in its transactions with China, Venezuela, and Iran. Similarly to Russia, Iran actively pursues de-dollarisation, as a response to what they both perceive as the “weaponization project of the dollar.”

In January, Iranian media reported that Russia and Iran had directly connected their banks through an inter-banking agreement to bypass SWIFT. Russia had also previously made the SPFS available to Iran. In August 2022, Iranian officials announced that a rial-rouble exchange had been created to de-dollarise trade with Russia. This was followed in December 2022 by the second largest Russian bank defying US sanctions by issuing rial-denominated payments to Iranian banks. Iranian officials announced in May that Russia’s VTB bank had opened its first representative office in Tehran, and in March they claimed an agreement had been reached for Russian credit card services to operate inside Iran. The intended purpose is to bypass Western services such as Visa and Mastercard, which are not operational in the two countries due to sanctions.

Russia and Iran have improved their bilateral banking ties, but they have so far been unsuccessful in creating a model for large-scale use. This failure is predominantly due to the lack of rouble and rial liquidity in their respective foreign exchange markets. Banks in Iran and Russia can support investment in small projects such as ports and railways. For bigger investment projects, Russia and Iran need major banks from China and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) involved. But these banks have so far been reluctant as they “simply do not want to give up access to US financing”.[30]

Investing in transit routes

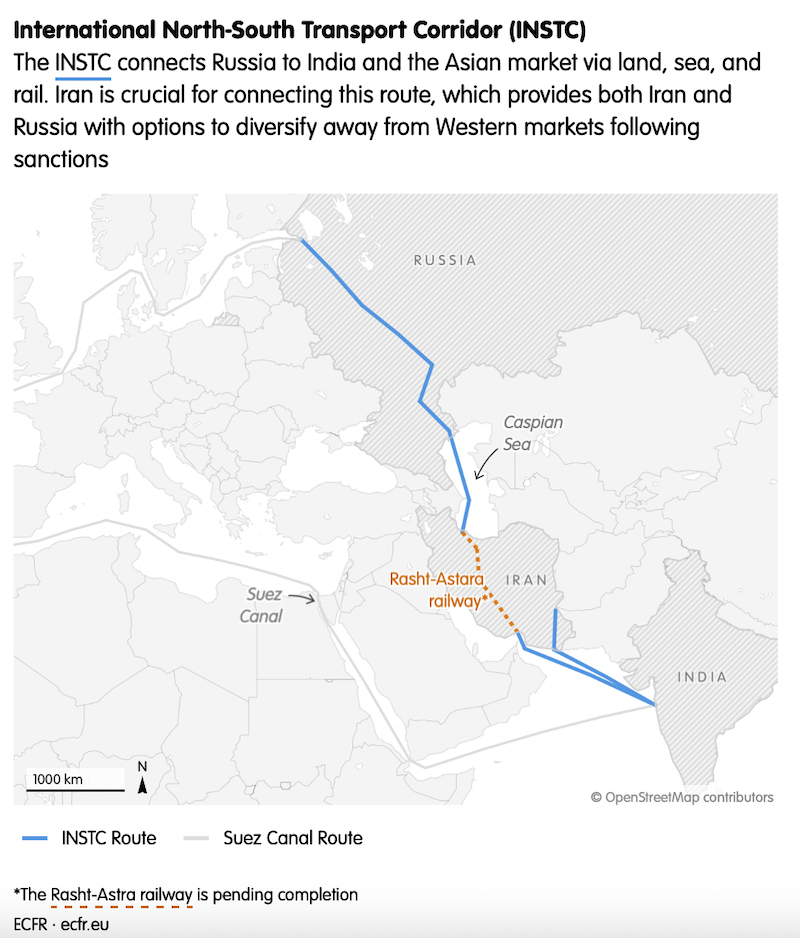

Iran’s geographical position means it has long sought to attract investment in the transit routes that connect Russia to Asia. The Caspian Sea and the International North-South Transit Corridor (INSTC) can provide road, rail, and sea connections all the way from northern Russia to India. These routes could play a key role in helping Russia augment its exports of agricultural and petrochemical products, machinery, and fertilisers into the vast Asian markets.

However, over the two decades since its launch, the INSTC has failed to progress due to lack of investment and sanctions against Iran. As one Iranian expert on Russia affairs notes, “if Russia looked at Iran more strategically, it would have invested more heavily in implementing the INSTC.”[31]

Russia’s appetite for such investment has changed following the Ukraine conflict. The Russian government now sees it as necessary to resolve logistical problems that have resulted from new Western sanctions and the consequent shift of economic activity to China, south-east Asia, and the Persian Gulf. The Rasht-Astara railway is a crucial node for the INSTC, and Putin and Raisi inked a new agreement in May for its construction.

However, the Russian-backed Eurasian Development Bank estimates that completing the INSTC will require a further investment of over $26 billion. It is unclear whether Russia, China, or India are willing or able to mobilise the money necessary to pay this bill. For example, India, as a founding member of the INSTC, is eager to invest in Iran’s Chabahar port. The US waiver that India obtained is however so restrictive that it has hindered the progress of the project. But, if Russia and Iran can succeed in attracting investment, the INSTC carries considerable potential to circumvent Western sanctions and boost their global trade.

Already, Iranian reports from 2022 suggest that trade through the INSTC has increased by 350 per cent. Iranian authorities hope to see the INSTC route fully operational by 2025, and some Iranian strategists believe the transit sector could ultimately generate more income for Iran than petroleum.

Energy cooperation

Russia and Iran have traditionally competed as energy exporters, but they are now signalling a desire to cooperate in this sector. Energy swap deals are taking place between them; Russia is expected to cut down its costs for delivering oil to Asian markets by using Iran as a storage hub.

In July 2022, Russia’s Gazprom also promised to invest $40 billion in Iran’s energy sector. This included an agreement with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) to develop Iranian oil and gas fields and construct gas pipelines. Iran’s energy infrastructure has lagged far behind its potential because of Western sanctions. Russia, meanwhile, is one of the world leaders in secondary gas production technology, an area in which Iran is desperate for investment.

Experts watching Iran-Russia trade relations[32] and economic leaders in Iran, however, doubt that major Russian investments in Iran’s energy sector will actually materialise. Gazprom’s track record is not reassuring. For example, in 2017, Gazprom agreed to invest in Iran’s Bushehr liquefied natural gas plant – but the project has not moved forward (in part due to US secondary sanctions). Even so, NIOC managing director Mohsen Khojasteh-Mehr predicts that Gazprom is more likely to stick to its word this time because of the new realities following Western sanctions against Russia.

Another limit on Russian investment is competition for oil markets. Immediately following the Ukraine war, and despite the increases in energy prices, Iran lost market share in places like China and India that increased their oil imports from Russia. Moreover, Iran’s energy exports are constrained by US secondary sanctions, which have not been applied to the same degree on Russian energy supplies.

But some energy experts point out that this initial competition is now being managed through the integrated world market, noting that “if Russian oil that used to go to North Africa or southern Europe is now heading to China, that market opens up. Iran is finding routes to these markets through Dubai-based traders. This is creating a new equilibrium.”[33] In August 2023, Reuters reported that Iran exported an estimated 3.15 million barrels a day, the highest since 2018.However, some experts argue Iran is unlikely to have access to the revenues from these oil sales due to US sanctions.

Another factor that might pave the way for Russian investments in Iran’s energy sector is that the Russian government is no longer as concerned about Iran becoming an alternative European energy supplier following the derailment of the JCPOA. Iran’s hardline leaders, unlike their predecessors, seem far less interested in exporting oil to Europe, and favour the geopolitical gains offered by a more cooperative energy stance towards Russia. Russia and Iran, however, still face the challenge of merging their hydrocarbon visions in the face of mutual competition and investment hurdles.

Future economic links

Despite the increased political will to cooperate on boosting economic links, Russia and Iran are unlikely to make advances soon in ways that will matter much to the Russian war effort in Ukraine. As one expert notes, “while new business is flowing … Moscow is unable to provide the investment Iran so badly needs,” and Tehran is “only able to provide part of the solution” for Russia in face of Western sanctions.[34]

For example, Iran’s strategic petroleum sector alone is estimated to require $250 billion in investment, an amount that is unlikely to come from Russia. As one economic expert notes, “Iranian economic sectors are subject to more US secondary sanctions than those of any other country. It doesn’t make commercial sense for Russian companies, like Lukoil, that have not been targeted by US secondary sanctions and continue global operations, to expose themselves to the Iran risk.”[35]

Nonetheless, recent developments in Russian-Iranian economic ties are noteworthy. The more Russian industries face sanctions and the less reliant they become on Western goods, the more likely it is that they will be prepared to engage in full-scale sanctions evasion with Iran.

Implications beyond Ukraine

Deepening ties between Russia and Iran have implications for European interests in three other important areas beyond Ukraine, namely the goal of restricting Iran’s nuclear programme, avoiding military escalation in Syria, and maintaining the West’s dominance within the global order.

Heightened risk of nuclear escalation

The Ukraine war significantly undermined Western efforts to constrain Iran’s nuclear programme. Compared to February 2022, Iran’s nuclear programme is now more advanced and less monitored. US officials estimate that Iran could make enough fissile material for one nuclear bomb in less than two weeks.

Historically, Russia played an outsized role as an intermediary on the nuclear file between Iran and the West. Moscow was also constructive during the Biden administration’s 2021 negotiations with Iran aimed at restoring the JCPOA. After Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine, however, Moscow acquiesced to Iran’s nuclear activities and spoiled Western efforts to roll back Iran’s nuclear programme. In March 2022, amid Western hopes of nearing a JCPOA revival, Russia derailed the talks by demanding a written guarantee that new Western sanctions related to Ukraine would not impede Russian trade with Iran.

Russia has also shielded Iran from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) – a body that Moscow has traditionally supported. In June 2022, 30 member nations of the agency’s board passed a resolution calling on Iran to cooperate with UN inspections of three undeclared nuclear sites. Russia rejected this resolution. After disconnecting agency cameras at nuclear sites, Iran faced no protest or expressions of concern from Russia, who instead blamed the board resolution for provoking Tehran.

Russia’s red lines over Iran’s nuclear activities appear to be shifting. Previously, Russia strongly opposed the idea of Iran enriching uranium to 90 per cent, recognising that such high levels have no civilian purpose.[36] This remains the official position but, according to several Russian experts, high enrichment levels are now tolerated.[37] One Russian nuclear expert outlines that there is little Russia could do if Iran decides to test nuclear weapons, concluding “so I guess mostly we’ll just accept it.”[38]

Overall, two schools of thoughts exist in Russia regarding Iran’s nuclear activities.[39] The first camp, backed by parts of the security apparatus, believes that a pro-Russian Iran matters more than preventing the development of an Iranian nuclear weapon. Members of this camp argue that the long-term benefits of close ties with Iran outweigh the risks associated with a nuclear-armed Iran. An Iran that remains under Western sanctions will also be more willing to support Russian interests, including in Ukraine. Some even welcome an Iranian nuclear weapon as a blow to a US-dominated international system.

The second school of thought, which remains the official Russian position, argues that a non-nuclear Iran matters more than a pro-Russian one. For members of this camp, Moscow should remain committed to curbing nuclear proliferation. Accordingly, the JCPOA’s restoration reduces the incentive for Iran to develop nuclear weapons, avoids a regional arms race, and prevents military actions against Iran.[40] As one Russian non-proliferation expert puts it, “if Iran moves towards the West eventually, and is armed with nuclear weapons, this would be a nightmare for Russia.”[41]

The longer the Ukraine war continues, and the more Russia becomes reliant on Iranian military assistance, the more likely it is that the first school of thought will come to dominate in Moscow.

Rattling the West in Syria

The war in Ukraine has also reverberated through the military campaign that Russia and Iran have undertaken in Syria since 2015 to support the regime of Bashar al-Assad. It has increased the risk of escalation inside Syria, between Iran and Israel, and among the US, Russia, and Iran.

To redeploy troops to Ukraine and reduce costs, Russian armed forces and the Russian private military company Wagner have reportedly evacuated some of their bases in central and eastern Syria, handing them over to Iranian and Hezbollah forces. But Russia maintains a military presence in Syria, with its aerial forces and Tartus naval base still key to its Syrian and wider regional posture.

Russia now appears to be working with Iran to increase the pressure on US forces in Syria. In March, the US reportedly expressed concern that Russian jets were no longer adhering to agreed deconfliction measures. Leaked US classified documents allege that Russian intelligence assisted Iranian militias to launch missile strikes on US military bases in Syria, including the Al-Tanf base in the south-east of the country. The US responded by increasing its presence in Raqqa in 2023 and with a series of strikes against Iranian-backed targets. In at least one case, Russia targeted US-backed rebels in Syria. In July, US and Russian forces had at least two skirmishes in the country, and the US claimed a Russian jet damaged a US drone over Syria. US officials describe this as part of a strategy to expel American troops from the country.

This escalation could be a joint effort by Tehran and Moscow to force the remaining 900 US troops out of Syria and thereby reduce Western pressure on their positions in the Middle East. Moscow and Tehran may also see it as a way to respond to increased sanctions pressures and the deadlock over nuclear diplomacy. However, since late March 2023, Iran has not backed attacks against US forces in Syria (or Iraq). This could potentially be connected to ongoing de-escalation talks between the West and Iran that began in late March.

Systemic rivalry

Putin and Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, have for some time been drawn together by a shared vision for a multipolar world order that diffuses power away from the West. Segments of the policy elites in both Iran and Russia see the Ukraine war as an opportunity to bring non-Western countries closer to their vision of this order.

To propel this agenda, Russia has increased its political and economic engagement with countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, in addition to organisations like the BRICS group of emerging economies, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), and the Eurasian Economic Union. Iran joined the SCO in 2022 and is expected to join the BRICS from 2024. It has also increased its engagement with Latin America and Africa, and rekindled political ties with Arab countries.

The political normalisation deal reached between Tehran and Riyadh in March assists Iran to draw the Arab world closer to the multipolar vision and to dilute Western dominance in the Middle East. The GCC countries, and in particular Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have also moved towards preferring a multipolar order in which they have greater autonomy from the West. These countries are reluctant to fully side with their traditional Western partners over the war in Ukraine, and have indirectly helped Russia’s war economy by pressing for production cuts that kept oil prices high. They have also accelerated economic ties to China despite the Western push for “decoupling” and “de-risking”. This assertive Arab position opens economic opportunities for both Moscow and Tehran to reduce the impact of Western sanctions.

Iran has also tried to lure Russia and China into efforts to “immunise” like-minded countries against Western sanctions. Even under the Rouhani administration, as Iran sought to remove US sanctions through the nuclear deal, it also pursued a parallel track to create a “resistance economy” that was more self-reliant and shock-proof against sanctions. Following the 2014 Crimea war, the Kremlin too has pursued self-sufficiency in the face of Western sanctions pressure and looked to Iran’s resistance economy as a case study.

In this effort, Russia and Iran are making the case to non-Western countries that de-dollarisation reduces the risks associated with sanctions and enhances their economic independence. So far, this has been an uphill struggle. In Russia and Iran’s view, the key to success is full Chinese participation in their vision for systemic rivalry with the West. The continued tensions between the West and China presents openings to draw Beijing deeper into this collaboration.

Iran and Russia, even with China’s help, have yet to introduce a competitive alternative to Western-led economic networks, but they are attracting more interest from the “global rest”. Partners of the West such as India, Brazil, Turkey, and the GCC states are increasingly looking to navigate between global powers. These countries have helped both Iranand Russia establish economic channels that bypass Western sanctions. They are also interested in working with China and Russia on testing mechanisms that might reduce dependence on the US dollar and SWIFT.

What Europeans can do

Overall, Iran and Russia have developed a deeper partnership that presents increased risks to the West. Leaders in both countries recognise the value in working together to safeguard their regimes in the face of Western pressures and rapidly changing geopolitical dynamics. Yet limitations in both countries, rooted in mutual distrust and practical constraints, mean that Iran and Russia are unlikely to form a tight strategic alliance with the promise of mutual defence akin to NATO.

Instead, the two sides are likely to prefer a flexible relationship that enhances their respective positions, especially vis-à-vis the West. Russia and Iran will not necessarily stand behind each other on every issue and they may well stab each other in the backs on occasion. However, Russia and Iran have a vested interest in ensuring that Western pressures do not fatally weaken either party. They are therefore likely to use, abuse, and rescue each other as and when it suits their strategic interests.

This type of Russian-Iranian relationship provides some limited but important openings for European countries. They should aim to slow down and reduce the likelihood that (1) Iran transfers more sophisticated weapons to Russia for use in Ukraine (such as even more lethal drones and missiles); (2) Iran advances its nuclear programme with tacit Russian approval; and (3) Syria becomes a theatre for increased escalation. To do so, European governments and the EU should pursue a policy that applies calibrated pressure on the cooperation between the two countries, but also offers some positive incentives to Iran.

Apply calibrated pressure

A key goal for Europeans should be to reduce the likelihood of more advanced Iranian weapons being supplied to Russia for use in Ukraine. One pathway to that goal is to limit Iran’s capability to produce such weapons. The EU introduced restrictive measures in October and December 2022 against entities and individuals involved with Iran’s drone programme. The US has also implemented several rounds of similar sanctions.

The EU should explore further sanctions and export controls to restrict the availability of Western or Asian dual-use goods and technologies used by Iranian drone manufacturers. Measures against Chinese and Turkish entities facilitating the transfer of Western goods to Russia and Iran could potentially degrade drone production. This will neither be a quick nor an assured way of reducing Iranian drone supplies to Russia given Iran’s current advanced drone production line. Indeed, Iran is increasingly using domestically produced parts for its Shahed drones. Domestic production will limit the effects of export controls, but they will remain important for some key foreign components that Iran still relies on.

In a scenario in which the Ukraine war is prolonged, such measures can also slow down the rate at which Iran and Russia produce more sophisticated drones. In parallel, the West will need to bolster Ukrainian defensive capabilities against Iranian-made drones used by Russia.

France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (the “E3”) also assert that Iran’s transfer of drones to Russia violates United Nations Security Council resolution 2231. This resolution enshrines the JCPOA and, among other things, places restrictions on Iran’s import and export of certain drones. These UN restrictions are set to expire in October 2023. In response, the EU, UK, and the US should bring together a coalition of like-minded states to retain national sanctions on Iran that ban the export of goods and technology related to missiles. This would send an important political message to Iran and would also limit its access to Western military technology and components.

Such an effort would be more effective than invoking the so-called “snapback mechanism” at the UN Security Council, which would automatically reimpose all UN sanctions on Iran that were lifted as part of the JCPOA. According to one former senior official, Iran would likely retaliate to such a move by expanding its nuclear programme and withdrawing from the Non-Proliferation Treaty.[42] It would likely also trigger further Iranian assistance to Russia in retaliation.

Another Western strategy targeting the Russian-Iranian relationship has involved leaking intelligence on their military cooperation. Such public exposure made it difficult for Iran to maintain the official government position that it is neutral in the Ukraine war. This has created friction within the Iranian leadership. The head of the UK’s MI6 notes that Iran’s military support to Russia has “has provoked internal quarrels at the highest level of the regime in Tehran.”

Europe and the US should continue working with Ukraine and other partner countries to publicise discussions and deals between Iran and Russia over their military cooperation, especially feeding this into Persian media networks. Azerbaijan’s geographical position, acrimonious relationship with Tehran over Armenia, and friendly ties with Israel open opportunities for greater intelligence collaboration by European governments to gain better insight into the transfer of arms between Russia and Iran via the Caspian Sea.[43]

Mark Dubowitz of the US-based Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, among others, advocates a more coercive approach. In this view, the West should take the war in Ukraine to Iran. In January 2023, a drone factory inside Iran was targeted, though it is not clear whether the attack had any link to the war in Ukraine. US officials suggested the attack was carried out by an Israeli drone and specifically denied such a link. Still, there has been some speculation that the drone factory in Isfahan supplied Russia. In response, Iran seems to have retaliated by launching attacks against an Israeli-linked vessel in the Gulf of Oman.

Iran and the US are also edging towards a shadow war over oil tankers. In April, Iran is believed to have countered a seizure of Iranian oil by the Biden administration through reciprocal moves against a vessel bound for the US. In July, the US is reported to have seized another tanker carrying Iranian petroleum. Days later, Iran made several attempts to seize other commercial tankers. In response, the US military has deployed 3,000 troops to the Middle East, and has proposed plans to allow armed marines and sailors to board commercial ships under threat from Iranian attack. If approved, this could place Iran and the US at greater risk of military confrontation.

Further covert or overt attacks against Iran risk significant consequences for Western interests. Iran could retaliate by intensifying military assistance to Russia inside Ukraine, increasing attacks against US forces in Syria, targeting Western diplomatic and military assets across the broader Middle East, and expanding its nuclear programme. At a time when European resources are focused on supporting Ukraine, the risks associated with such coercive measures would be great.

Conduct hard-nosed diplomacy

Beyond coercion, European governments need to have an accompanying political agenda to tackle deepening Russian-Iranian ties. As long as the Ukraine war rages, options to peel Moscow away from Tehran do not exist. There may however still be some openings with Iran. This will not secure an Iranian realignment with the West but could put some brakes on the more problematic elements of its relationship with Moscow. The fact that even under the most hardline government, Iran keeps talking about the need for a nuclear deal, and the supreme leader has allowed for continued diplomacy with the West (on releasing Western detaineesand the nuclear file) suggests that Tehran still wants the benefits that could come from deal-making with the West.

European countries and the US should work to shift political calculations in Tehran. Since March 2023, the West has been signalling that it wants to renew diplomacy. Senior E3 and EU political directorshave met with their Iranian counterparts on several occasions. The US has engaged in bilateral indirect talks with Tehran. These talks have focused on a series of mutual de-escalatory measures between the West and Iran. This includes the potential release of five US nationals detained by Iran that were placed under house arrest in August as part of a deal with Washington. In return, the US has reportedly agreed to provide special guidance to its sanctions allowing South Korea to transfer Iranian frozen assets to Qatar, to be used for humanitarian trade.

To build on this momentum, European officials should increase their diplomatic efforts in the coming months. They should focus on securing measures that reduce the strategic threats they face from the evolving Russian-Iranian cooperation.

Firstly, Iran should halt the forms of military cooperation with Russia that significantly enhance Moscow’s ability to cause destruction in Ukraine. Iran would cease joint Russian-Iranian and possibly Belarusian-Iranian production of more advanced drones. It would also agree not to deliver missiles to Russia as long as the Ukraine war continues.

Secondly, Iran should take steps that cap and eventually roll back its nuclear programme. This can start with a freeze of uranium enrichment levels at 60 per cent and then a steady reduction over the coming months. Iran should also agree to immediately increase IAEA access and monitoring to verify the peaceful nature of its nuclear programme, including IAEA access to data stored in cameras at Iranian nuclear facilities.

Thirdly, Iran should cool military tensions with the US through a public agreement to halt attacks against one another’s assets inside Iraq and Syria – a de facto development since March 2023. Such an agreement would reduce Russia’s ability to use Iranian assistance in its attacks against US-allied forces inside Syria.

In exchange, the West needs to put forward a competitive economic offer to Iran. Here European countries can take advantage of some lingering doubts within the Iranian system as to whether Russia is able and willing to fulfil its promises on military and economic cooperation. Russia’s economic weakness means that the West is much better placed than Russia to relieve Iran’s current economic difficulties. This effort would require European governments to simultaneously press the US to ease secondary sanctions while also pressing Iran to reduce its military assistance to Russia and freeze its nuclear enrichment activities. Providing such an alternative path for Iran’s economic recovery might also reduce the speed at which Moscow and Tehran collaborate on systemic rivalry with the West.

Europe and the US should stress that they can offer Iran immediate economic advantages in ways that are not open to Russia and China. For example, Western capitals could ease Iran’s access to its frozen assets, estimated to be worth billions of dollars, held abroad. The West could also allow for increased Iranian oil exports (that will most likely be directed to non-Western markets). Importantly, easing US sanctions could enable Iran to access its revenues from oil sales that remain trapped in third countries due to US financial restrictions. In the first stage of talks, access to such funds should be restricted to humanitarian trade. Europe could also offer to provide Iran with an attractive offer for grain imports (perhaps even supplied by Ukraine). Iran is heavily reliant on such imports (including from Russia) because its domestic production has been hit badly by drought. Working with the US, Europeans should put these immediate financial offers on the table.

The ongoing thaw in Arab-Iranian relations provides the West with other options for economic diplomacy with Tehran. The US could provide sanctions relief in areas where Iran and the GCC can jointly advance regional economic trade and projects. Iraq is a natural venue for such initiatives. If Iran is more economically integrated with the GCC states and Iraq, this could put a brake on how far Iran would risk jeopardising these gains through its partnership with Russia. This de-escalatory path is also likely to reduce the risks of undesirable military tensions in Syria.

Unlike past rounds of Western negotiations with Tehran, the suggested diplomatic approach aims to link nuclear, regional, and Russia-related security threats. While the scope is broader than the JCPOA, the duration of such a deal would be more limited. The aim of a package like this is to prevent escalation between the West and Iran over the course of the Ukraine war, and at least until after the 2024 US presidential election. As such, the economic rewards offered to Iran will be limited to smaller and one-off immediate measures. Similarly, Iranian steps will not transform the nature of its nuclear programme, its overall regional positioning in Syria, or its relations with Russia. This pathway buys time for Europeans to fend off the worst threats it faces from the emerging Russia-Iran relationship, as well as preserve space for a more serious diplomatic endeavour with Iran if a political opening emerges.

The diplomatic approach also comes with risks. Firstly, the process could break down. This could be triggered by escalatory dynamics in the region or over the nuclear programme, sparked by Iranian or Israeli action. The process could also derail because Russia provides Iran with an offer too good to refuse, for example Su-35 fighter jets or significant investments in Iran’s energy sector. Another risk is that the Iranians use the talks to stall for time or divide Europe and the US from their common stance.

In such scenarios, European countries should affirm that if Iran’s military cooperation with Russia deepens in detrimental ways for Ukraine, Iran risks permanently burning its bridges with Europe. Considering the 2024 US elections, European governments should also privately stress to Tehran that while in the past they parted ways with US regime change and maximum pressure policies, this is not guaranteed if Iran poses even greater security threats to Europe.

A further risk with this approach, is that by striking a deal with Iran, European governments will be seen as legitimising the leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran at a time of deep unpopularity within the country. But the deal proposed would not create a major flow of funds that would further entrench the power of the Iranian leadership (as the 2015 nuclear deal had the potential to do). Moreover, diplomacy does not mean that Iran will get a free ride on its abysmal human rights record. The West should continue to shine a light on these issues, mobilise global pressure against Iranian repression, and offer tangible support to ordinary Iranians.

The moment is now

Russia and Iran are advancing their economic and security partnerships in ways that were unimaginable just a few years ago. These ties have deepened as Moscow seeks to secure critical military supplies from Tehran and the two countries attempt to find lifelines for their sanctions-battered economies. Their intensified cooperation in the past year has imposed costs on European security in Ukraine and has the potential to cause still greater damage.

The moment to influence the Tehran-Moscow trajectory is now. If Russia and Iran further strengthen their ties, it may become impossible to ever come between them. The simultaneous isolation of both Iran and Russia provides formidable incentives for the continuance of their cooperation. The West needs to make more effective use of its coercive tools to come between Russia and Iran, but it will need to offer some incentives as well, especially to Iran.

The combination of coercive options and economic incentives presented here contain some real risks. But, given the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, European governments should see limiting the military partnership between Iran and Russia as a strategic priority. In that context, this approach has the potential to reduce the direct threats to Europe by slowing down and hopefully blocking Iranian military cooperation with Russia inside Ukraine.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the numerous policy officials and experts from Iran, Russia, Europe, and the US who shared their insights in the research for this paper, especially those interviewed. Some officials, former officials and interviewees based inside Iran and Russia requested to remain anonymous for security reasons or due to the sensitivity of the topic being discussed. The authors are very grateful for the support of ECFR colleagues, including Julien Barnes-Dacey and Jeremy Shapiro. They owe special thanks to ECFR’s Elsa Scholz for her research assistance and to Nastassia Zenovich for producing the infographics for this paper. The authors would also like to thank the generous donors of the Middle East and North Africa programme, who made this publication possible.

[1] Comment by Iran-based security expert, meeting held off the record, Brussels, May 2023. [2] Interview with Gustav Gressel, ECFR senior policy fellow, email, April 2023. [3] Interview with Gustav Gressel, ECFR senior policy fellow, email, April 2023. [4] Interview with Gustav Gressel, ECFR senior policy fellow, email, April 2023. [5] Comments by a former senior Iranian official, meeting held off the record, Brussels, January 2023. [6] Comments by British, French, and EU officials; meetings held off the record; London, Paris, and Brussels, January-May 2023. [7] Comment by a former senior European official, meeting held under the Chatham House Rule, online, April 2023. [8] Interview with Mahmood Shoori, senior researcher at the Institute for Iran-Eurasia Studies, online, May 2023. [9] Comments by European officials, meetings held off the record; Brussels, London, and Paris; January-March 2023. [10] Interview with Russia-based defence expert, online, May 2023. [11] Comments by Western defence expert, meeting held under the Chatham House Rule, online, June 2023. [12] Interview with Russia-based defence expert, online, July 2023. [13] Interview with senior Russia-based expert on Russia-Iran relations, online, April 2023. [14] Discussion with Iran-based defence expert, online, July 2023. [15] Interview with Abdolrassol-Farzam Divsallar, political scientist, online, April 2023. [16] Comments by US officials, meeting held off the record, Washington DC, October 2022. [17] Interview with Abdolrassol-Farzam Divsallar, political scientist, online, April 2023. [18] Interview with Abdolrassol-Farzam Divsallar, political scientist, online, April 2023. [19] Interview with Mahmood Shoori, senior researcher at the Institute for Iran-Eurasia Studies, online, May 2023. [20] Interview with Abdolrassol-Farzam Divsallar, political scientist, online, April 2023. [21] Interview with senior Russia-based expert on Russia-Iran relations, online, April 2023. [22] Interview with Javad Heiran-Nia, director of Persian Gulf Studies at the Center for Scientific Research and Middle East Strategic Studies, online, May 2023. [23] Comment by Iran-based security expert, meeting held off the record, Brussels, January 2023. [24] Comment by Iran-based security expert, meeting held off the record, Brussels, January 2023. [25] Interview with former senior Iranian official, online, April 2023. [26] Interview with senior Russia-based expert on Russia’s economic relations, online, April 2023. [27] Interview with senior Russia-based expert on Russian-Iranian relations, online, April 2023. [28] Comments by Iran-based senior business executive, meeting held under the Chatham House Rule, online, April 2023. [29] Interview with Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, CEO of Bourse and Bazaar Foundation, London, April 2023. [30] Interview with Bijan Khajehpour, economist and managing partner at Eurasian Nexus Partners, online, April 2023. [31] Interview with Mahmood Shoori, senior researcher at the Institute for Iran-Eurasia Studies, online, May 2023. [32] Interview with Bijan Khajehpour, economist and managing partner at Eurasian Nexus Partners, online, April 2023; interview with Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, CEO of Bourse and Bazaar Foundation, London, 6 April 2023. [33] Interview with Bijan Khajehpour, economist and managing partner at Eurasian Nexus Partners, online, April 2023. [34] Interview with Bijan Khajehpour, economist and managing partner at Eurasian Nexus Partners, online, April 2023. [35] Interview with Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, CEO of Bourse and Bazaar Foundation, London, April 2023. [36] Discussion with Russian nuclear experts, online, March 2023. [37] Interview with a former Russian diplomat and nuclear expert, online, April 2023. [38] Interview with a former Russian diplomat and nuclear expert, online, April 2023. [39] Interview with senior Russia-based expert on Russia-Iran relations, online, April 2023. [40] Interview with senior Russia-based expert on Russia-Iran relations, online, April 2023 [41] Interview with a former Russian diplomat and nuclear expert, online, April 2023. [42] Comments by a former senior Iranian official, meeting held off the record, Brussels, January 2023. [43] Interview with an Azerbaijani official, online, July 2023 Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News