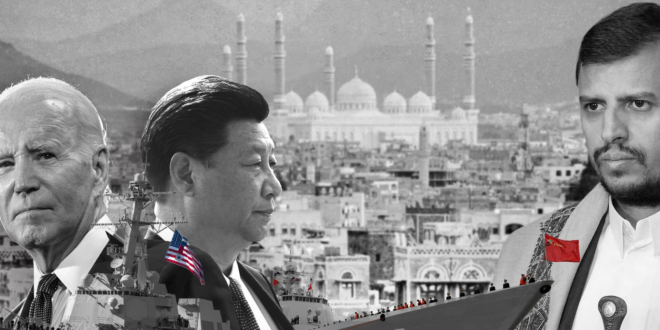

Despite Beijing’s maritime security priority, Ansarallah’s Red Sea ban on Israeli-linked shipping has boosted China’s regional standing while miring its US adversary in an unwinnable crisis.

The Gaza war’s expansion into the Red Sea has created an international maritime crisis involving a host of countries. Despite a US-led bombing campaign aimed at deterring Yemen’s Ansarallah-aligned navy from carrying out missile and drone strikes in the Red Sea, the armed forces continue to ramp up attacks and now are using “submarine weapons.”

As these clashes escalate dangerously, one of the world’s busiest bodies of water is rapidly militarizing. This includes the recent arrival to the Gulf of Aden of a Chinese fleet, including the guided-missile destroyer Jiaozuo, the missile frigate Xuchang, a replenishment vessel, and more than 700 troops – including dozens of special forces personnel – as part of a counter-piracy mission.

Beijing has voiced its determination to help restore stability to the Red Sea. “We should jointly uphold the security on the sea lanes of the Red Sea in accordance with the law and also respect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the countries along the Red Sea coast, including Yemen,” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi emphasized last month.

As the largest trading nation in the world, China depends on the Red Sea as its “maritime lifeline.” Most of the Asian giant’s exports to Europe go through the strategic waterway, and large quantities of oil and minerals that come to Chinese ports transit the body of water.

The Chinese have also invested in industrial parks along Egypt and Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coasts, including the TEDA–Suez Zone in Ain Sokhna and the Chinese Industrial Park in Saudi Arabia’s Jizan City for Primary and Downstream Industries.

Chinese neutrality in West Asia

Prior to the sending of the 46th fleet of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy, Beijing’s response to Ansarallah’s maritime attacks had been relatively muted. China has since condemned the US–UK airstrikes against Ansarallah’s military capabilities in Yemen, and refused to join the western-led naval coalition, Operation Prosperity Guardian (OPG).

China’s response to mounting tension and insecurity in the Red Sea is consistent with Beijing’s grander set of foreign policy strategies, which include respect for the sovereignty of nation-states and a doctrine of “non-interference.”

In the Persian Gulf, China has pursued a balanced and geopolitically neutral agenda resting on a three-pronged approach: enemies of no one, allies of no one, and friends of everyone.

China’s position vis-à-vis all Persian Gulf countries was best exemplified almost a year ago when Beijing brokered a surprise reconciliation agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, in which it played the role of guarantor.

In Yemen, although China aligns with the international community’s non-recognition of the Ansarallah-led government in Sanaa, Beijing has nonetheless initiated dialogues with those officials and maintained a non-hostile stance – unlike many Arab and western states.

Understanding Beijing’s regional role

Overall, China tries to leverage its influence in West Asian countries to mitigate regional tensions and advance stabilizing initiatives. Its main goal is ultimately to ensure the long-term success of President Xi Jinping’s multi-trillion dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and keep trade routes free of conflict.

Often labeled by the west as a “free rider,” China is accused of opportunistically benefiting from US- and European-led security efforts in the Persian Gulf and the northwestern Indian Ocean without contributing to them.

But given China’s anti-piracy task force in the Gulf of Aden and its military base in Djibouti, this accusation isn’t entirely justified.

Beijing’s motivations for staying out of OPG were easy to understand: first, China has no interest in bolstering US hegemony; second, joining the naval military coalition could upset its multi-vector diplomacy vis-à-vis Ansarallah and Iran; and third, the wider Arab–Islamic world and the rest of the Global South would interpret it as Chinese support for Israel’s war on Gaza.

Rejecting the OPG mission has instead bolstered China’s regional image as a defender of the Palestinian cause.

Speaking to The Cradle, Javad Heiran-Nia, director of the Persian Gulf Studies Group at the Center for Scientific Research and Middle East Strategic Studies in Iran, says:

[Beijing’s] cooperation with the West in securing the Red Sea will not be good for China’s relations with the Arabs and Iran. Therefore, China has adopted political and military restraint to avoid jeopardizing its economic and diplomatic interests in the region.Dropping the blame on Washington’s doorstep

Beijing recognizes the Red Sea security crisis to be a direct “spillover” from Gaza, where China has called for an immediate ceasefire.

As Yun Sun, co-director of the China Program at the Washington-based Stimson Center, informed The Cradle:

The Chinese do see the crisis in the Red Sea as a challenge to regional peace and stability but see the Gaza crisis as the fundamental origin of the crisis. Therefore, the solution to the crisis in the Chinese view will have to be based on ceasefire, easing of the tension and returning to the two-state solution.

Jean-Loup Samaan, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute, agrees, telling The Cradle:

Chinese diplomats have been carefully commenting on the events, but in Beijing’s narrative, the rise of attacks is a consequence of Israel’s war in Gaza – and perhaps more importantly the US policy in support [of] the Netanyahu government.

But in January, after the US and UK began their bombing campaign of Ansarallah targets in Yemen, China began to weigh in with serious concerns about the Red Sea crisis. Beijing noted that neither Washington nor London had received authorization for the use of force from the UN Security Council, and, therefore, as Sun explained it, the US–UK strikes “lack legitimacy in the Chinese view.”

How the Red Sea Crisis benefits Beijing

China has capitalized on intensifying anger directed against the US from all over the Islamic world and Global South. The Gaza war and its spread into the Red Sea have delivered Beijing some easy soft-power gains and reinforced to Arab audiences the vital importance of multipolarity.

This point was drummed home by Victor Gao, vice president of the Center for China and Globalization, when he told the 2023 Doha Forum:

The fact that there is only one single country which [on 8 December, 2023] vetoed the United Nations Security Council Resolution calling for ceasefire in the Israel-Palestine War should convince all of us that we should be very lucky living not in the unipolar World.

Certainly, China has experienced some economic repercussions from the Red Sea crisis, although the extent of this is difficult to calculate. Yet Beijing’s political gains appear to trump any associated financial losses. As Sun explained to The Cradle, “The crisis does affect China, but the loss has been mostly economic and minor, while the gains are primarily political as China stands with the Arab countries on Gaza.”

In some ways, China has actually gained economically from the Red Sea crisis. There is a widespread view that Chinese ships operating in the area are immune from Ansarallah’s maritime attacks..

After many international container shipping lines decided to reroute around South Africa to avoid Ansarallah’s missiles and drones, two ships operating under the Chinese flag – the Zhong Gu Ji Lin and Zhong Gu Shan Dong – continued transiting the Red Sea.

As Bloomberg reported early this month:

Chinese-owned merchant ships are getting hefty discounts on their insurance when sailing through the Red Sea, another sign of how Houthi attacks in the area are punishing the commercial interests of vessels with ties to the West.

US officials have since implored Beijing to pressure Iran into ordering the de-facto Yemeni government in Sanaa to halt maritime attacks. Those entreaties have failed, however, largely because Washington has made flawed assumptions about Beijing’s influence over Tehran and incorrectly assessed that Iran can make demands of Ansarallah. Regardless, the fact that the US would turn to China for such help amid escalating tensions in the Red Sea is a boost to Beijing’s status as a go-to power amid global security crises.

China also has much to gain from the White House’s disproportionate focus on Gaza and the Red Sea. Since October–November 2023, the US has had significantly less bandwidth for its South China Sea and Taiwan files. In turn, this frees Beijing to act more confidently in West Asia while the US remains distracted. According to Heiran-Nia:

The developments in the Red Sea will keep America’s focus on the region and not open America’s hand to expand its presence in the Indo–Pacific region, [where] America’s main priority is to contain China. The war in Ukraine has the same advantage for China. While the connectivity of the Euro–Atlantic region with the Indo–Pacific region is expanding to contain China and increase NATO cooperation with the Indo–Pacific, the tensions in [West Asia] and Ukraine will be a boon for China.

Ultimately, the Red Sea crisis and Washington’s failure to deter Ansarallah signal yet another blow to US hegemony. From the Chinese perspective, the growing Red Sea conflict serves to further isolate the US and highlight its limitations as a security guarantor – particularly in light of its unconditional support for Israel’s brutal military assault on Gaza.

It is reasonable to call China a winner in the Red Sea crisis.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News