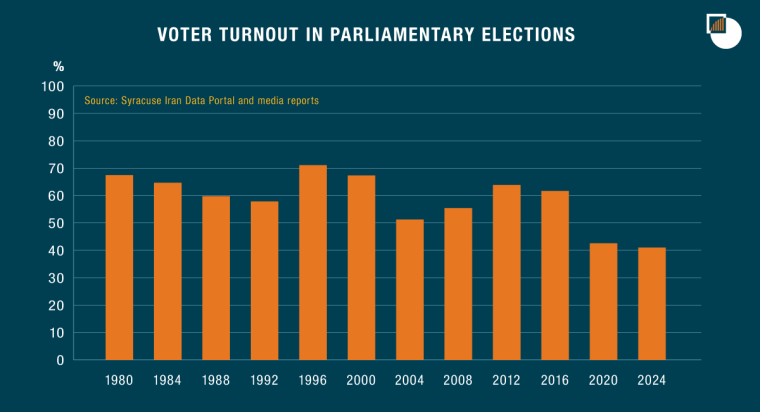

Turnout in Iran’s national polls was historically low, marking the third vote in a row in which most people stayed away. In parallel, conservatives tightened their hold on the Islamic Republic’s institutions. The two trends together highlight the growing gap between state and society.

On 1 March, Iran held its twelfth parliamentary election since the 1979 revolution as well as its sixth contest for the Assembly of Experts, the clerical body nominally tasked with selecting the next supreme leader. Official results indicate a turnout of 41 per cent, marking a historic low for the legislative race and the third consecutive electoral cycle in which the majority of voters stayed away – a sign of widespread frustration with the system and scepticism that political change can occur via the ballot box. The elections took place against the backdrop of severe economic, security, political and social challenges, as well as growing questions about who will succeed the present supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is 84. Almost three years after conservatives – adherents of the Islamic Republic’s core ideology – consolidated control of all branches of government, infighting within their ranks has intensified. So, too, has public discontent, as manifested in repeated rounds of mass unrest, the most recent being the nationwide “woman, life, freedom” demonstrations that erupted in September 2022 over the death of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, in “morality police” custody. The state violently repressed the protests, which shook the country for months.

Taken together, the population’s growing dissatisfaction and the system’s overt effort to deepen conservative political dominance underscore a widening divide between state and society. Should this gap continue to grow, it could put the country’s stability at risk. Yet for Iran’s leadership, the overriding imperative is strengthening ideological conformity and political control at the top, even at the cost of losing ever more of its legitimacy from below.

Shaping the Twelfth Parliament

Iranian elections have always been tightly regulated. But the trendline since 2020 has been one of increasingly restricted political expression, and falling participation, resulting in largely uncompetitive races with predictably conservative outcomes. In both the 2020 parliamentary elections and the 2021 presidential race that brought Ebrahim Raisi into office, the Guardian Council, an unelected oversight body, barred candidates who could threaten a conservative victory. These races saw historically low turnouts as well. These developments have allowed conservatives to cement their grip on both the parliament, or Majles, and the executive, giving them control of all instruments of power given that the judiciary, whose head is appointed by Ayatollah Khamenei, was already in their hands.

In the lead-up to the 2024 vote, there were already clear signs that, once again, turnout would be low and the system would hold another uncompetitive election to entrench conservative dominance, reflecting the deepening influence of its most ideologically hardline elements. In July 2023, an amendment to the parliamentary election law added more layers to process for vetting candidates, including expanding the authority of the above-referenced Guardian Council to shape the outcome of national polls. This change, most notably, gave the Council the power to disqualify politicians not just before the elections but even after voters had elected them. Critics including the Reformist Front, comprising over 30 reformist factions, decried the move as manipulation further tilting the playing field in the conservatives’ favour. Breaking with its tradition, the Front refrained from issuing a statement encouraging its members and supporters to register as candidates for the parliamentary race. Anticipating unfair elections, many reformist figures, whose fortunes have dwindled in recent years, did not register at all.

” [Turnout in the national polls] seemed all but certain to be depressed given the open wounds of the brutally crushed 2022 protests and persistently dire economic conditions. “

The system’s tighter exclusionary approach toward the elections further dimmed the prospects for turnout, which seemed all but certain to be depressed given the open wounds of the brutally crushed 2022 protests and persistently dire economic conditions. State-linked polling data leaked in 2023 projected just 30 per cent participation. Apathy and disillusionment had reached such an extent that even the idea of registering to run in the elections could elicit negative responses.

Torn between the desire to maintain a façade of electoral legitimacy and purging the system of even its loyal critics, the leadership simultaneously encouraged the people to register and tightened the screws on its vetting process. On paper, the parliamentary contest looked quantitatively impressive. When the parliamentary campaign officially began in August 2023, nearly 49,000 persons pre-registered to run – a figure almost three times higher than in 2020. Part of the reason was new measures: an Interior Ministry text message campaign inviting people to sign up and a streamlined online registration process. About 25,000 candidates completed their registration after authorities had verified their personal information. Subsequently, the Interior Ministry and Guardian Council approved the eligibility of around 15,200 candidates – again, three times the 2020 pool and the largest in post-revolutionary history. But, in this case, quantity did not translate into quality, as most of these candidates were not well-known figures.

Not surprisingly, the system’s critics started calling for snubbing the elections. For example, Narges Mohammadi, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, issued a statement from Tehran’s Evin prison urging people “to declare the illegitimacy of the Islamic Republic” by boycotting the vote, a step she described as “a political necessity and a moral duty”. In the charged atmosphere, many politicians, including former officials, calculated that their participation would be construed as endorsement of an electoral ruse.

” The Reformist Front announced that … it would not endorse any candidates for office. “

Discredited after years of encouraging voting despite the unfree, unfair nature of Iranian elections, only to see the conservatives stymie any possibility of reform, the Reformist Front announced that, unlike in 2020, it would not endorse any candidates for office, though it stopped short of calls to boycott the elections. Most of the Front’s politicians believed that they could not persuade people who had lost hope in the ballot box to vote for them. A senior Front member told Crisis Group that “if society still had any trust in us … then we could have participated in the elections, even with proxy candidates with no organisational ties to us”. By choosing to abstain, they aimed to contribute to a record-low turnout, showing solidarity with the frustrated citizenry, while hoping against hope that the government would realise the urgency of overhauling its approach to governance.

Beyond the boycotters and the tactically disengaged, there was another constituency looking for a way to express its opposition to the regime. This group comprised a minority of reformists, along with some centrists, who in Iran’s fluid factional landscape stand between the reformists and conservatives. They sought to dilute the hardliners’ strength by electing at least a few parliamentarians who could voice popular demands – essentially, a protest bloc operating within the system’s parameters. These factions endorsed 165 candidates, gaining support from figures like former President Hassan Rouhani (himself a centrist). Rouhani urged people to buck the disengagement trend and vote for candidates disgruntled with the status quo. “This is the first time I see that both the ruling minority and a majority of the public want the same thing”, Rouhani said in January. “The ruling minority wants an election where no one shows up at the ballot box. The majority of people don’t want to cast votes”.

In the end, though, neither reformists nor other political opposition were in a position to mount a meaningful challenge to the conservative camp. The latter, in turn, found itself consumed with internal rather than external political battles. The major fault line was competition among conservative establishment and hardliners; the latter espouse, even by regime standards, stridently ideological views on social, cultural and foreign policy issues. In some instances, conservative politicians launched highly personal attacks upon one another, resulting in multiple candidate lists in several populous districts. Three main factions conducted separate campaigns: the Coalition Council, whose members are more technocrats and allies of Parliament Speaker Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf; the Unity Council, representing the old-guard traditional conservatives; and the hardline groups, mainly the Endurance Front.

Election Results

While some parliamentary results are technically pending run-offs, the big picture was clear before ballots were cast: not only tightened conservative control, but an increasingly hardline bent. The centre of Iranian politics will thus shift further to the right – a pattern that is now nearly two decades old. Overall, 245 candidates were elected, with second rounds needed to determine the fate of 45 other seats in fifteen provinces, including Tehran, where none of the candidates passed the 20 per cent threshold of valid votes. It seems that around 40 candidates endorsed by reformist and centrist factions have secured seats, though it remains to be seen whether they can coalesce in an effective minority bloc.

Despite the regime’s effort to cajole strong participation – and notwithstanding its claims of succeeding in that goal – the numbers show a depressed picture. Turnout continued its decline to a post-1979 nadir – 41 per cent, by the official tally (which some think is inflated), 1.5 per cent lower than in 2020; all but a handful of provinces recorded lower turnout than four years ago. As in the past, turnout fared better in the peripheries, where voters are apt to choose politicians whom they believe will advocate in the capital for investment in local development. It was highest – at 65.74 per cent – in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmed, a south-western province home to a significant Lor ethnic minority. But even there it dropped from 70.66 percent in 2020. In contrast, the populous Tehran, Alborz and Esfahan provinces saw some of the lowest rates, ranging from 26 to 37 per cent.

” While conservatives secured around half of the 30 seats, the remainder were left vacant due to a failure to hit a minimal threshold of 20 per cent of valid votes. “

The participation rate in the city of Tehran, where voting patterns are more of a political barometer, has not yet been officially announced. But initial results indicated that while conservatives secured around half of the 30 seats, the remainder were left vacant due to a failure to hit a minimal threshold of 20 per cent of valid votes. No reformist or centrist won, and none is among the 32 candidates competing for the remaining sixteen seats in the runoff. Seyed Mahmood Nabavian from the doctrinaire Endurance Front emerged as the top vote winner in Tehran – a symbolic victory that positions him as a potential candidate for the parliament speakership, whose embattled incumbent, Qalibaf, finished fourth in the number of votes. Remarkably, however, Nabavian’s tally was still around 30 per cent less than that of the candidate who finished thirtieth in vote count in 2020 and less than any other candidate who ranked first in Tehran over the last eleven electoral cycles.

The highly limited contestation could produce only one outcome: a conservative victory. In these circumstances, the record-low turnout was likewise no surprise. But two important developments stand out. First, even some of the system’s loyal opposition appear to have abandoned hope that the Islamic Republic’s elections can deliver a better future. One such figure who refrained from voting was former reformist President Mohammad Khatami, who had always advocated using any opportunity, however slim, to pursue course corrections via the ballot box. “This time, I decided that if I can’t do anything for the people, I will stand in solidarity with the multitude of discontented individuals”, Khatami said. Secondly, even if one takes the announced turnout at face value, it tells only part of the story of a profoundly disaffected electorate. For the third national election in a row, the majority abstained from voting. Of those who did participate, according to the official figures, 8 per cent (equivalent to roughly 3 per cent of all eligible voters) cast invalid ballots, in what some interpret as an intentional act of protest.

For a system born of a popular revolution and which has long heralded voter participation as a measure of its legitimacy, the continued slippage of turnout ought to ring alarm bells about the extent of public discontent. Yet the regime has celebrated the election results as a victory over the opposition at home and abroad, claiming the polls were successful because the turnout was only marginally off from 2020. Ayatollah Khamenei, who once derided 40 per cent participation rates in other countries as a “shameful” sign of popular mistrust in government, called the 2024 turnout a “remarkable, epic move”, foiling purported foreign plots against participation. This veneer of victory claimed by the establishment not only overlooks the growing lack of support from 60 per cent of the electorate, but also risks entrenching the government’s tendency to double down in the face of growing challenges instead of addressing core grievances. Such self-approbation mirrored the regime’s previous dismissal of the 2022 protests as the result of foreign intrigue, rather than a reflection of deep, simmering public discontent – a dangerous pattern that could eventually undermine the country’s stability.

Assembly of Experts

At the same time that they voted for the twelfth parliament, Iranians chose among candidates for the Assembly of Experts, an institution that wields the power to determine the system’s most influential role – that of the supreme leader. With 88 seats up for grabs, the council, comprising exclusively jurists (experts in Shiite Islamic jurisprudence), is increasingly in the spotlight given the supreme leader’s advancing age and thus the looming question of succession. The assembly, which convenes for eight-year terms, has historically exercised its authority only to appoint the leader, with other responsibilities that it enjoys under the constitution, such as dismissal of, and supervision over, the leader, remaining untested.

” The elections were barely competitive in around half of Iran’s provinces. “

The 2024 assembly elections marked a notable decline in engagement among the clergy, with only 501 jurists registering to run – a sharp decrease from the 801 candidates in the previous cycle. The Guardian Council further narrowed the field, approving just 144 contenders in a stringent vetting process. Thus, the elections were barely competitive in around half of Iran’s provinces, with the number of candidates less than twice the number of seats. In one province, for example, five seats were contested by only six individuals. Among the prominent figures barred from running was former President Rouhani, a three-time Assembly incumbent. Rouhani’s disqualification signalled that the country’s conservative leadership has no appetite for hearing even modestly dissenting views when it comes time to decide who and what will follow Ayatollah Khamenei. But even such measures may not prevent considerable fractiousness within the conservative camp when the time comes to determine his successor.

The results indicate that 45 per cent of the Assembly’s composition has changed, with most of the incoming jurists closely affiliated with Ayatollah Khamenei. Tellingly, Mohammad Sadegh Amoli-Larijani, a former chief justice and the current head of the Expediency Council, a body that advises the supreme leader, who had become critical of the Guardian Council’s exclusionary practices, failed to garner enough votes to keep his seat. He was widely considered a potential successor to Khamenei. Thus, even the circle containing the system’s most trusted insiders is continuing to shrink.

The Big Picture

The conservative drive to dominate all branches of government in the Islamic Republic is an attempt at political “purification”, eliminating moderate elements from governance to create even more space for the next generation of adherents to the revolutionary worldview. Its proponents believe that the government, military and other institutions need to be cleansed of all those whom they consider disloyal or ideologically wobbly. Such sentiments are longstanding, and various oversight bodies like the Guardian Council – which reviews electoral slates to remove those it considers ideologically beyond the pale – have intervened for years to stymie development of the system’s republican aspects. But these efforts seem to be accelerating, and the parameters of who is deemed acceptable as a candidate in national elections narrowing, over the last four years, as Ayatollah Khamenei’s succession looms larger. As Abbas Abdi, a prominent Iranian sociologist put it, “We have passed the initial stages of purification, and now reached the enrichment phase. The advanced political centrifuges are spinning at maximum speed”.

The consolidation of power among the regime’s most conservative elements bodes ill for its ability to address Iran’s accumulating challenges. The state of the economy remains woeful, despite modest growth after a decade-long slump. Diplomacy that could help it, by securing relief from U.S. and other sanctions, appears moribund, while corruption and mismanagement are pervasive. The government’s pivot toward closer ties with Russia and China has yet to yield tangible economic benefits. With inflation soaring above 40 per cent over the last three years, purchasing power has plummeted, with no major relief in sight. The national currency has been particularly volatile; since Raisi’s inauguration in 2021, the exchange rate has surged from 250,000 rials to the dollar to more than 600,000. The security apparatus smashes peaceful dissent with an iron fist, but it has failed to repel recurrent attacks by state and non-state adversaries. In the political sphere, the divided conservative camp has struggled to legislate effectively, failing to pass key bills, including those promoting transparency – a core commitment of the outgoing eleventh parliament.

” The … government has imposed more conservative cultural mandates, a move at odds with a society leaning toward diminished religiosity. “

The same government has imposed more conservative cultural mandates, a move at odds with a society leaning toward diminished religiosity, as evidenced by state-conducted polls. In the summer of 2021, Raisi decreed additional dress code restrictions for women, leading the “morality police” to accost more women its officers judged to be immodestly attired. These policies are broadly unpopular. Outrage at them erupted as part of the 2022 protests, which quickly took a wider anti-regime tone. Polls indicate that over three quarters of the population are either unconcerned with women forgoing the hijab or inclined to keep their objections to themselves when they encounter a woman not wearing one. The government highlighted its intrusive approach when parliament enacted the Rejuvenation of the Population and Support of Family Law in November 2021, which imposes fresh limitations on women’s reproductive rights. In this and other realms, government decrees and public attitudes are ever more dissonant. Its inclination to suppress socio-political frustration instead of addressing its root causes prompted former President Khatami to warn that the system was “overthrowing itself” by doubling down on, instead of reconsidering, unpopular policies.

The prognosis for the Islamic Republic is bleak: a government formed by a shrinking minority, pursuing maximalist ideological goals that are deeply out of sync with those of a growing majority. While minority rule does not pose an imminent existential threat to the system, it will almost certainly further weaken it in the long run. The disconnect foreshadows continued failures in addressing social, political and economic challenges, and thus a deepening legitimacy crisis for the Islamic Republic and its ostensibly representative institutions. If the goal is to concede on popular legitimacy in favour of unity at the top, even that may prove questionable: internal conservative disputes, centred not on ideology but on power struggles, will hamper efforts to consolidate power in preparation for an inevitable leadership transition.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News