Abstract: Following the 9/11 attack, the United States led the international community to fight jihadi terrorism. Over 20 years later, jihadi violence in the West is low, but the number of Sunni jihadi outfits around the world has increased. And while the central leaderships of both al-Qaida and the Islamic State appear in tatters, many of their affiliates are experiencing expansion. This article takes a holistic view of the jihadi movement, examining all of it—not just its two heavyweights, al-Qaida and the Islamic State, and their affiliates. It argues that factors of continuity, such as anti-regime grievances, the appeal of religious ideology, and the ability to hurt, are likely to maintain jihadism as a viable resistance ideology. It is true that the global ambitions of transnational jihadi groups have suffered setbacks in recent years and their actions have been hindered by material weaknesses, the power of nationalism and of sub-national identities, as well as internal conflicts among the movement’s leaders. However, jihadism is still a powerful force and is making inroads in various regions. The article warns that a more modest jihadi strategy with a regional focus is offering jihadis a new path forward, but also suggests that a sustainable jihadi success would require moderation that is simply antithetical to the nature of the ideology.

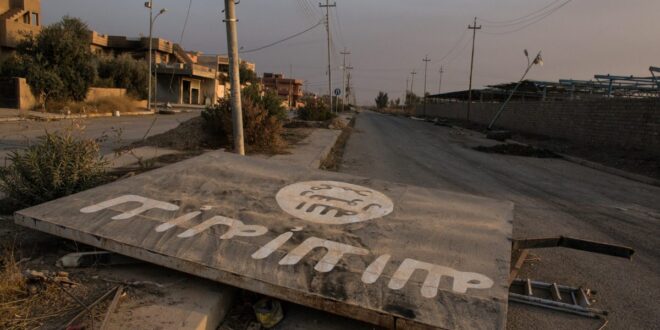

Recent years have been hard on the central leaderships of the jihadi movement’s heavyweights, the Islamic State and al-Qaida. The Islamic State lost its territorial possessions in the Middle East and has been cycling through leaders, losing three in less than two years.1 Meanwhile, al-Qaida has not carried out a spectacular terrorist attack in the West in nearly two decades, and in July 2022 lost its leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in an American strike. Over a year later, it has yet to announce a successor.2 Other jihadi groups had better fortune: The Taliban has returned to power in Afghanistan, while jihadi groups operating in Africa and affiliated with al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State have been making gains, especially in the Sahel.3 How does one make sense of these diverging trends and what do they reveal about the future of the jihadi movement?

Several scholars have warned that both policymakers and many academics are prematurely dismissing the potency of the jihadi threat.4 This article does not reject these warnings, but seeks to assess the future of Sunni jihadism in a more comprehensive manner, not looking only at the transnational jihadi groups, their affiliates, or a particular region, but at the broader jihadi movement. The guiding logic behind this choice is that the state of jihadi groups is not merely a function of their confrontation with enemy states, but also of the appeal of dissimilar jihadi objectives and strategies. Consequently, while transnational jihadi groups appear in decline, jihadism is here to stay. Factors of continuity, such as anti-regime grievances, the appeal of religious ideology, and the ability to hurt, are likely to maintain it as a viable resistance ideology. The hopes for better lives and greater freedoms expressed by millions during the Arab uprisings failed to translate to significant change, but they did not die. In fact, as long as some Muslims continue to strive for change, jihadism will remain a natural ideological resource. In the West, jihadism will also remain attractive for some struggling young Muslims.

At the same time, jihadis are hindered by perennial material weaknesses, the power of nationalism and of sub-national identities, and internal conflicts among the movement’s leaders.5 Such factors seem particularly detrimental for al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State, but might be less consequential for jihadi groups with narrower focus. Indeed, though the transnational model of jihadism, with its universal goals, has likely hit a wall, events such as the Gaza war may offer jihadis a chance to rejuvenate. Additionally, a more modest strategy with a regional focus, such as what is happening in the Sahel, seems to offer jihadis a new path forward. Moreover, contrary to Usama bin Ladin’s conclusions, the cases of the Taliban in Afghanistan and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in Syria’s Idlib province demonstrate that local jihad could result in some success. However, sustainable jihadi success—at the state, regional, or international level—would require moderation that is simply antithetical to the nature of the ideology and is more likely to produce criticism by other forces within the movement than to serve as a model for imitation.

Although the United States has begrudgingly accepted jihadi rule in some locations (e.g., post August 2021 Afghanistan), the United States and the international community continue to fight jihadis elsewhere (e.g., Somalia). This variation does not necessarily indicate misguided policies. However, it raises the suspicion that the U.S. and its Western allies have not developed a holistic view of the threat posed by the jihadi movement, and a coherent position on how much tolerance jihadism may receive. Now, when the jihadi threat to the West is in decline, and concomitantly, political pressures on governmental strategic planning are low, it would be wise if the United States planned for a possible upcoming jihadi resurgence.

This articlea is divided into five sections. In the first, the author offers background about the jihadi movement from its inception as a transnational movement during the 1980s. The second section focuses on the manner in which anti-regime grievances, framed through a religious lens, and the continued ability to hurt enemies, are likely to sustain jihadi violence for years to come. The third section focuses on the weakness of the jihadi movement, highlighting jihadis’ material weakness, their focus on bound-to-fail social engineering, and their proclivity for internal conflicts. The strategic options available for jihadi groups are explored in the fourth section, before the fifth section concludes with a discussion of the jihadi movement’s path forward.

The Jihadi Movement

Though jihadi groups operated in different Muslim countries (notably Egypt) prior to the 1980s, the war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan brought together members of jihadi groups and unaffiliated foreign volunteers, ultimately turning disparate actors into a social movement. This jihadi social movement includes multiple actors pursuing dissimilar objectives and using diverse strategies. Today’s jihadism involves established local, regional, and transnational groups alongside independent radical scholars, unaffiliated foreign fighters, cell-sized small leaderless groups, online sympathizers, and lone wolves. What unites Sunni jihadis and allows seeing them as components of one movement is their belief that an armed jihad is not only an instrumental necessity in order to restore ‘Islamic’ glory and helping oppressed Muslims, but is also a value in its own right. Some jihadis even elevate jihad further, claiming that there is no act of worship equal to jihad.6 Like other social movements, the jihadi movement features an important layer of agreement (the centrality of jihad), but also great variation between its numerous components.

Following the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, jihadis sought to harness the power of the movement and continue to operate elsewhere. They did not agree, however, on where they should direct their energies. Consequently, the 1990s were characterized by two jihadi strategic directions: one focused on fighting local regimes deemed insufficiently Islamic (‘the near enemy’) and the other focused on fighting non-Muslim forces occupying Muslim lands. Both strategies had important adherents, but success was elusive and, when experienced (in the cases of Bosnia and Chechnya), short lived.7 Bin Ladin and al-Qaida offered a way out of the rut, proposing a third strategy that put the United States—‘the far enemy’—at the center. Al-Qaida proposed jihadis would be able to attain their objectives in Muslim countries only after dealing with the American backers of Middle Eastern regimes. This strategy was based on provoking U.S. overreach, drawing the United States into a war of attrition it could not win, and using American excesses to mobilize a large number of Muslim sympathizers.

Despite two large scale attacks—on the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania (1998) and on the USS Cole (2000)—only after the 9/11 attacks did a deeply wounded and enraged United States shift its focus to jihadi terrorism. The United States swiftly shifted from underestimating the jihadi threat to exaggerating it, for a while making it the country’s main strategic priority. Shocked by the devastation, it acted as if 9/11 reflected the true scale of jihadi capabilities, rather than a fluke success attributable primarily to failures of the U.S. intelligence community and lax security conditions that are unlikely to be repeated. The U.S. response produced dubious results, which exposed the limits of its power. Although it did not experience another large-scale jihadi terrorist attack on its homeland, the United States came far from eliminating jihadi terrorism. In fact, since 9/11 and the subsequent U.S. quagmires in Afghanistan and Iraq, the jihadi movement has increased in size, geographical reach, and number of attacks.8 Moreover, as one observer notes, U.S. actions may have even increased instability throughout the world.9

Sustaining Factors

Though it has been about four decades since its emergence, some of the conditions that facilitated the rise of the jihadi movement are unlikely to change significantly. Some Muslims are likely to 1) retain anti-regime grievances; 2) find a religious frame to understand their grievances and to suggest a response; and 3) maintain the ability to hurt their enemies. Together, these factors suggest that the claimed decline of the jihadi movement in recent years is hardly a harbinger of the movement’s end.

- Continued Anti-Regime Grievances: A significant number of Muslim-majority countries have long suffered from repression, corruption, and poverty, producing numerous popular grievances against their rulers: It is no wonder jihadism emerged first in localized national contexts. The Arab Spring uprisings—the clearer expression of public dissatisfaction over the direction their countries are heading—brought a brief period of optimism, but no functional democracy has emerged in the Middle East and many lives have only further deteriorated under corrupt leaders and declining economies. Even Tunisia, long hailed as the one success story of Arab democratization, has since returned to its authoritarian ways.10

One may find cause for optimism in the success of Saudi Arabia (in pursuit of its Vision 2030) and other Gulf states in adopting more liberal policies and promoting economic development. These efforts have been received positively by many young Muslims, weakening jihadis’ ability to capitalize on what they see as “un-Islamic behavior” for increased recruitment. Deradicalization programs, especially in Saudi Arabia, also offer some promising ways to reduce the appeal of jihadis. However, the applicability and sustainability of these developments is unclear. There is still a not insignificant number of Saudi zealots who could be motivated to fight the regime for what they see as violation of Islamic tenets. Moreover, what may work in rich Arab countries could fail in poorer Muslim states that either would not take such expensive endeavors or would fail to implement them, assuring that anti-regime grievances that lead to jihadi mobilization will persist.

Recruitment could also be bolstered by dissatisfaction over governments’ reaction to external events (for example, Muslims’ displeasure with their governments’ responses to the ongoing war in Gaza). While jihadi attacks and challenges are not necessarily expected in all Muslim countries, and are not necessarily imminent, their continued potential must be recognized.

Similarly, Muslims residing in non-Muslim countries, particularly in the West, are likely to retain grievances against the non-Muslim majority and state authorities. These grievances may not be based on actual religious discrimination, but often will be framed in this way, whether by jihadi proponents or by populist right-wing parties in the West. For example, though many of the problems faced by French Muslims living in poor suburbs reflect societal ills, they were often portrayed and understood by politicians and even scholars as reflecting Muslims’ inability to embrace Western values.11 Rising tensions in the Middle East, particularly between Israel and the Palestinians, serve as another mechanism that could increase jihadi attacks in the West,12 primarily via lone wolves or through small groups of aggrieved individuals who came together as a by-product of the mobilization for pro-Palestinian demonstrations. Such attacks are likely to focus on Jewish targets but may also seek to target states viewed as overly supportive of Israel. Ultimately, between governments’ failed integration efforts, populist right-wing parties promoting Islamophobia, and jihadi entrepreneurs who frame grievances in religious terms, some Muslims in the West are likely to be hostile to, and to take action against, their states.

- Religious Frames and Solutions: Jihadism is likely to remain an available ideology to guide those seeking to fight over their grievances. Though Islam is not the only ideological resource that anti-regime activists could use to challenge their rulers, it is a natural reservoir of ideas about how to understand the reality of the inhabitants of Muslim countries or of Muslims in non-Muslim countries and about what sort of action must be taken to remedy injustices. This is especially the case in Muslim-majority countries that rely on the country’s religious identity to legitimize the regime’s rule, such as Saudi Arabia. The use of Islam for regime legitimacy is a double-edge sword: It can strengthen regime stability, but it also exposes the regime to attacks by religious extremists challenging its understanding of Islam. Even when a regime in a Muslim-majority country does not seek religious legitimacy, Islamically appropriate behavior may still be important for large percentages of the population. Jihadis thus offer a religious alternative to failing secular systems.

It is true that the overwhelming majority of Muslims reject jihadi views of Islam.13 Furthermore, as the cases of Saudi and other Gulf regimes show, states may gain domestic legitimacy through economic development and social change, rather than based on religion and piety. However, the sustainability of that model and the reforms it is based on are still in doubt. It is also doubtful it is a viable option for poorer Muslim countries. Moreover, even if most Muslims accepted the new direction their countries are taking, all it would take for a jihadi threat to emerge is a small group of dedicated operatives holding a religiously extreme ideology. In fact, reforms that would be viewed as undermining the Islamic nature of states, could serve as a cause for jihadi violence. Finally, given that Islamic texts, like those of all religions, can be interpreted in a radical way and some Muslims adhere to radical understandings of Islam, the jihadi movement should be able to survive.

In Western countries, a jihadi ideology could be particularly salient. In Muslim countries, jihadis debate about what constitutes “proper” Islam. In the West, however, both Islamists and right-wing populists seek to highlight the distinctions between Muslims and the rest of the public. One of the Islamic State’s objectives in its attacks in the West was to ‘erase the gray zone’ that allowed Muslims in the West to ignore the fact that they live among non-Muslims. These were designed to increase Islamophobia so that Western non-Muslims would view all Muslims as a threat and make their living in the West unbearable, even impossible. The Islamic State hoped that by triggering further Islamophobia, it could persuade Western Muslims to either immigrate to the Islamic State’s territories or stay in the West to commit terrorism in its name.14 Events such as the war in Gaza may further alienate some European Muslims,b dissatisfied by their countries’ responses, and push them to join the jihadi efforts.

- The Ability to Hurt: The 9/11 attack was a tremendous, but catastrophic, success for al-Qa

ida. The United States and many other countries treated 9/11 not as an exception, but as a reflection of al-Qaida’s prowess. For that reason, the United States focused considerable attention and resources on preempting a second strike.15 In reality, 9/11 relied on U.S. intelligence failures and lots of luck.16 The attack shows an actor may occasionally punch above its weight, even if only briefly.

Jihadi actors seem incapable of repeating 9/11-scale attacks, but their ability to hurt is hardly insignificant. Indeed, technological advances make planning attacks, as well as obtaining or producing means of violence, easier. There are also many low-tech options for jihadis that involve the easy repurposing of objects as weapons (for example, using a car to run over people or rigging toy drones with explosives). In the United States, easy access to firearms ensures that determined jihadis could cause lots of damage.

Meanwhile, states’ abilities to stop non-state violence is limited. Many states, especially in the West, are well positioned—with the aid of technological advancements—to prevent the worst terrorist attacks, and they often succeed in reducing jihadis’ access to lethal weapons. But such success only mitigates the threat; it does not eliminate it. Small-scale attacks, especially by previously unknown perpetrators, are notoriously hard to stop.17 Though the strategic value of such attacks is in doubt, many jihadi perpetrators are content to carry out attacks with a low fatality count because they still provide them with a sense of contribution to the general fight and assurances about their imagined place in heaven.

The impact of the ability to hurt depends not only on the level of violence, but also on how states perceive the damage they suffered (often informed by the public’s response to the attack). Attacks producing the same number of fatalities can result in varied levels of public pain and public pressure for a particular type of state response. Prior expectations also matter. A state accustomed to a certain level of violence may feel lesser pressure to react to jihadi attacks.

Ultimately, the long odds jihadis face will not necessarily discourage their operations. Under the guise of religion, many see victory over the ‘infidels’ as inevitable, even if it takes a long time, because it is divinely ordained. Religious precepts are also used to explain away defeats.18 Moreover, jihadi actors focusing on short-term objectives, such as preventing a regime from establishing order, releasing prisoners, or avenging fallen comrades, may continue operating even when the chances of achieving their long-term political objectives are slim.

Though the motivation for anti-state action, extreme Islamic precepts, and the ability to hurt are likely to remain relevant, these are not the only factors determining the magnitude of the jihadi threat. States’ perceptions often miss the true objective scale of the threat. States that ignored the rise of jihadism, or that, like Pakistan, tried to ride the jihadi tiger, paid a heavy price.19 On the other hand, states that overreacted to jihadi attacks caused chaos that ultimately benefited jihadi groups. The U.S.-led 2003 invasion of Iraq, for example, brought new life to the jihadi movement, which was on the ropes at the time. Thus, states’ actions, especially responses to jihadi violence, could counterproductively impact the appeal of jihadism and encourage jihadi mobilization.

The Weaknesses of the Jihadi Movement

Though anti-regime grievances, the centrality of Islam, and the ability to hurt point to the potential longevity of jihadism, the movement simultaneously suffers from endemic problems that reduce its appeal and effectiveness. First, jihadis tend to be weak actors, relatively small in numbers, and lacking in resources compared to their state enemies. The more encompassing the political entity they seek to create, the less likely they are to produce a winning strategy and the more likely they are to trigger a foreign intervention. Capabilities are, thus, a primary challenge. Second, jihadis seek to reorganize society. However, the more their success depends on social engineering, the less likely they are to succeed. Third, the more encompassing a group’s objectives, the more likely they are to trigger internal conflicts within the movement.

- Power and Strategy: Jihadis face problems similar to other armed non-state actors challenging state authorities. In almost all cases, the state is stronger than its non-state challengers. In fact, the use of terrorism is often indicative of non-state actors’ weakness.20 Stronger groups may be able to turn to insurgency tactics, but even they face long odds. Moreover, even weak states are not easy to beat, especially when they receive foreign aid. Jihadis’ revisionist goals and their violent and repressive ideology often lead states to view them as an international problem and thus trigger external involvement in a way other non-state actors do not.21

Before 9/11, jihadis, having failed in their limited struggles against the ‘near enemy,’ were unprepared for large-scale initiatives. Bin Ladin nonetheless opted for an ambitious strategy, taking on the greatest power in the international system.22 Al-Qa`ida’s lack of sufficient resources was only part of the problem: Tailoring an appropriate strategy to jihadis’ political objectives magnified the challenge,23 and the greater the ambition, the harder it was to design an effective strategy.

In al-Qa`ida’s case, bin Ladin’s America-first strategy required attacking the United States in a manner that would force it to abandon its Muslim allies. The strategy was linked to notions of U.S. hegemony and was ripe with misperceptions about the United States’ role in the world, Muslim regimes’ agency, and jihadi power and appeal. The Arab Spring uprising exposed the strategy’s flaws. Contrary to bin Ladin’s predictions, Arab publics brought down oppressive regimes, including American allies, but the United States did not intervene. In Libya, the United States even actively contributed to the regime’s downfall.24

The Islamic State’s caliphate-based strategy offered a means to unite Muslims against their non-Muslim enemies while de-emphasizing the United States’ centrality to jihadi plans. As a caliph has authority over all Muslims, no matter where they reside, the caliphate was conceived to unite the umma, the Muslim nation, in general, and the jihadi movement in particular, behind the Islamic State. Such a strategy allowed maximizing the ‘umma’s’ potential to protect Muslims from non-Muslim enemies and launching a campaign to expand the territory under ‘Islamic’ rule.25 However, the group’s leaders exaggerated their ability to force unity on all jihadis, let alone appeal to the Muslim masses. Importantly, it did not have a successful strategy to link together islands of jihadi rule and create a viable contiguous state.26

Although the Islamic State achieved more than any other jihadi group, its success was still very limited and short-lived, exposing the group’s limitations and, more generally, the limits of the jihadi project. Transnational jihadis seek to bring Muslims of different states together under one political authority. Such a goal requires not only scoring success in several geographical locations, but also linking them together to create a bigger and more powerful entity that can proceed the expansion process.27 But the Islamic State, even at its peak success (2014) was unable to aggregate its different operations. Under near ideal conditions (weakness of the Iraqi regime and military, no U.S. forces present in Iraq, and turmoil across the border in Syria due to civil war), it was able to erase, at least for a while, the borders between Iraq and Syria, but go no further.28 Elsewhere it relied on isolated islands of territorial control, only to reveal that its expansion efforts were quickly being met by its opponents’ power.29

Central to jihadism’s weakness is its inability to offer a solution for its vulnerability to air power. The Islamic State’s greatest success took place before the United States joined the fight. Once the United States brought its airpower, the Islamic State’s ability to expand was curtailed, as became evident in the battle for the Syrian Kurdish border town of Kobani (fall 2014). U.S. airpower forced the Islamic State to move away from deploying battalion-size formations to using much smaller units that would be less vulnerable to attacks from the air.30 But such a reorganization also meant the Islamic State lost its ability to conduct large-scale conventional operations whenever a credible aerial threat existed.

Given these shortcomings, jihadis are more likely to succeed when fighting in the periphery, and especially in weak states that feature multiple fighting forces and the disinterest of great powers. Jihadis have a track record of linking themselves to local conflicts. In weak states, where state authorities have little control, society is fragmented, and order lacking, jihadis can take advantage of regimes’ limits to establish bases of support (including local safe havens), gain resources, and more generally, fill power vacuums left by failing governments.31 However, jihadi power is constrained in such locations as well because jihadi groups often get entangled in tribal rivalries. Furthermore, each jihadi success increases the threat of a foreign intervention, as shown by the 2013 French intervention that destroyed jihadi rule in northern Mali. Jihadis may have an easier time if they quickly topple a local regime and assume control over its military assets, especially airplanes (and in Pakistan, the holy grail—nuclear weapons). However, quick success is extremely rare. Moreover, locations where such a jihadi strategy may succeed are not likely to supply jihadis with sufficient capabilities (airpower in particular) and trained manpower to effectively use against technologically advanced militaries.

- Social Engineering: In jihadi eyes, religion trumps all other identity markers and should be the primary factor informing individual and communal behavior. Initially, jihadi groups focused on toppling local regimes and establishing, in their stead, sharia rule. These are objectives that may change the nature of individual states, but not of the international system. Following the rise of al-Qa`ida and then the Islamic State, jihad has undergone an upward scale shift. No longer mere lip service to the global umma, transnational jihadi groups have taken the fight against the ‘infidels’ to the global level, envisioning jihad as mandatory until Islam reigns supreme. Such a vision conflicts with the state-based order and the quest for interstate peace and stability.32

Instead of settling for power within the existing society of states, the transnational variants of the jihadi movement that have come to dominate the movement are seeking to overturn the system. They seek a shift from a state-based order to radical Islamist order; from one encompassing multiple actors holding equally legitimate rights and obligations to one dominated by a caliphate in which there is no room for other states (let alone non-Muslim states); and from one in which all people are deemed equal to one in which non-Muslims are inferior. This attitude, elevating religious above national identity, is also manifested in the call on Muslims to become foreign fighters.33

The rise of transnational jihadi groups complicated the activities of localized jihadi groups as well. The United States’ failure to make sense of the diversity within the jihadi movement led to the capture of many non-al-Qa`ida jihadis, even though they did not seek to fight the United States.34 Unable to escape the trap, some jihadi groups, such as the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG),35 issued long revision documents and abandoned violence.

Others formed relations with al-Qaida, which began branching out in 2003, incorporating local jihadi groups. The Islamic State followed suit in the following decade, incorporating localized conflicts into the jihadi transnational campaign. Such expansion gave localized conflicts a stronger religious flavor. But it came with a price, weakening the ability of these new al-Qaida and Islamic State outfits to use nationalistic tropes as a way to strengthen their local appeal. Expansion also boosted the anxieties of external actors, increasing the threat of external intervention. Ironically, notwithstanding the global aspirations of al-Qaida and the Islamic State, and the statements their branches have been issuing in response to events outside their immediate conflict zone,36 their branches still maintained their focus on local enemies (to the chagrin of al-Qaida leaders), producing internal incoherence as both al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State faced conflicting impulses.37

The formation of al-Qaida and Islamic State branches essentially coopted local jihads into the grand vision of a global caliphate. Over time, however, it became evident that these affiliates did not abandon their local focus, even as they maintained their formal allegiance to their organizations’ transnational leadership. As the examples of al-Qaida and Islamic State affiliates JNIM, ISWAP, and ISCAP show, a formal affiliation with the two transnational jihadi heavyweights could aid—or at the least, does not necessarily harm—the armed expansion of local jihadi groups. However, while the benefits of affiliation might be sufficiently great for jihadi groups in the periphery, they are more limited in areas of greater strategic significance in the heart of the Middle East. Perhaps the greatest disadvantage of affiliation with al-Qaida and the Islamic State is that such affiliation denies jihadi groups international political legitimacy, needed for sustainable political gains. Facing this dilemma, HTS signaled a shift back to the model of local jihad, when it abandoned, by 2017, its affiliation with al-Qaida and stated its disinterest in fighting outside of Syria.38 Even bin Ladin recognized the costs of affiliation for local groups, advising the Somali al-Shabaab to keep its close relationship with al-Qa`ida a secret.39

Jihadis’ social engineering efforts went beyond the intended shift from a state-based order to a religiously based order. It required radical change in the way people, especially Muslims, perceive themselves and their religion. The transnational jihadi groups envisioned a world in which Muslims prioritize their religious identity, relegating other identity markers to inferior significance, or all together to oblivion. This is a problem for many Muslims who are attached to their national and tribal identities. It is much worse for non-Muslims who would end up relegated to the bottom of the social ladder.

Transnational jihadis’ plans for such a transformation proved detached from Muslims’ realities. Most Muslims still see their state or clan, not their religion, as their primary political identity marker. And as the Saudi case, noted above, reveals, when the state delivers on its social and economic promises, popular public opinion strengthens its position, while reducing the appeal of religious zealots. Moreover, even Muslims who prioritize religion tend to hold much more moderate views of Islam than jihadis. They may hope for more Islam in family affairs, but not in politics.40 In fact, the overwhelming majority of Muslims worldwide reject jihadism, especially its transnational variant, as too extreme.41 A majority of Muslims also dislike the idea that Islamic scholars (even non-jihadis) would assume a greater role in government.42 These Muslim attitudes reduce the potential of jihadi mobilization and indicate that jihadis must overcome not just non-Muslim opposition but also Muslims’ attitudes, effectively rendering the achievement of their political objectives pipe dreams.

- Intra-Jihadi Conflicts: Though internal disagreements are common in social movements, their impact is greater in armed extremism. This is especially true in the jihadi movement because the material weakness jihadis face in attaining their more expansive objectives requires considerably greater cooperation. But the jihadi camp is plagued with internal conflicts that not only prevent collaboration but also produce fratricidal violence.43 Often clothed as religious differences, these internal conflicts tend to become a matter of binary choice between good and bad, rather than a legitimate difference of interpretation. Moreover, viewed as a matter of ‘Islamically’ correct behavior, jihadis often reject other jihadis’ position as incompatible with Islam, thus making a compromise much harder and escalation likelier.44

Internal divisions have characterized the jihadi movement since the 1980s, especially as veterans of the war in Afghanistan contemplated their next fight. The main disagreement was between fighting the ‘near enemy’ and fighting a ‘defensive jihad’ against foreign occupiers.45 It was a source of tension during that time in part because jihadis competed over the same funding sources: bin Ladin and his Saudi connections.46 While during the 1990s jihadis pursued both goals, they still argued about which was a priority; jihadis especially disagreed about the Islamic legitimacy of the Taliban regime.47

The appearance of transnational strategies made direct conflict among jihadis more likely. Transnational strategies conflicted with those focused on fighting the ‘near enemy.’ Moreover, viewing intra-movement relations through the lens of authority and allegiance escalated disagreements as they were often seen as a manifestation of some jihadis’ apostasy (punishable by death), rather than a matter of normal difference of opinions. The Islamic State’s declaration of a caliph and a caliphate magnified jihadi internal conflict. Claiming global authority, the Islamic State was unwilling to tolerate diversity within the movement and sought to dominate it. Instead of accepting the promotion of multiple jihadi projects simultaneously as legitimate, the Islamic State sought to control all jihadis, demanding they dismantle all groups and accept its sole authority. Those refusing the caliph’s authority were labeled enemies and even apostates. As a result, rather than uniting all jihadis under one group, the Islamic State increased internal divisions and led jihadis of different groups to be preoccupied with each other, sometimes at the expense of the original reason for their formation, fighting against their adversaries.48

Strategic Options

Looking to the future, what strategic options are available to the jihadi movement? Thus far, the movement has presented five main strategies:

fight the ‘near enemy.’ Although in theory jihadis could pursue a military coup (an approach the Egyptian Islamic Jihad favored), fighting the ‘near enemy’ usually meant organizing the masses against the regime.49

fight non-Muslim countries that invaded a Muslim country (‘defensive jihad’);50

fight the ‘far enemy,’ primarily the United States, seen as preventing jihadis from toppling the local regimes;51

form a caliphate to mobilize the umma for both ‘defensive jihad’ to protect Muslims and their lands, and for ‘offensive jihad’ to expand the territory under Muslim control;52

rely on lone wolves producing numerous attacks.53

Although all these strategies were tried and failed, they did not all lose their appeal. Some could be revived if perceptions change about their past utility and there are new conditions more conducive to their success. Ironically, the America-first strategy, which bin Ladin championed and resulted in the expansion of the jihadi movement, appears the least suitable at present. In addition to its shortcomings noted earlier, one wonders how relevant this approach is given shifts in the global balance of power and emerging multipolarity. Due to these systemic changes, this strategy could neither provide a solid story why and how fighting the United States would resolve the umma’s problems, nor account for the expanded role of other actors in the international system. China, in particular, must now be incorporated into any transnational jihadi narratives. It increased its involvement in Muslim countries considerably in the past decade,54 while at home China is engaging in what U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken called “ongoing genocide and crimes against humanity” of its Uyghur Muslim minority.55

Notwithstanding the shifts in the global balance of power, which weakened the strategic justification for attacking the United States, successful attacks on the United States might still be attractive as a way to signal audacity to fellow jihadis and attract new recruits. Sara Harmouch offers a compelling argument that under al-Qaida’s new leadership, it has been building capacity and planning for such attacks.56 It will not be a surprise if al-Qaida will wait until it is ready to carry out a new spectacular attack before announcing a new leader. Although a strategy focused on the United States is bound to fail, strong and lingering anti-American sentiments make hurting the United States still highly appealing to jihadis. U.S. support for Israel’s war on Hamas provides additional incentives for attacking American targets. However, while the will is there, al-Qa`ida’s ability to inflict priorities-changing attacks on the United States is in doubt.

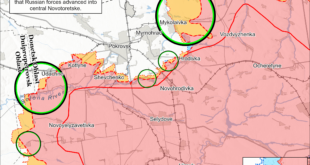

The caliphate-based strategy that the Islamic State promoted saw early success, but the collapse of the caliphate exposed the model’s shortcomings. Islamic State rule never resembled the ideal visions of life under a caliphate, but its ultimate failure did not destroy jihadis’ dreams about its future restoration. Moreover, though this grand vision suffered a severe hit when the Islamic State lost its territories in Iraq and Syria, ideas about islands of jihadi rule that would over time be consolidated into fewer and larger political entities are likely to remain appealing. Although the Islamic State could not hold its possessions in the strategically important Middle East, the periphery (especially Africa), where disorder and military coups are common, state control is weak, and borders are porous, offers much better prospects of growth and success as evidenced by the expansion of al-Qa`ida’s JNIM and the Islamic State’s Sahel branch.57 But the Islamic State’s attempt to create an enduring caliphate also reveals that attempts to foist a caliph on Muslims will be poorly received. Moreover, appropriating the caliph position and demanding subservience from other jihadi groups could produce infighting and consequently undermine the movement’s goals.58

More limited strategies may have better chances of success. Though the international community proved wary of jihadi states, when these states appear sufficiently constrained and unlikely to be used to destabilize other (especially neighboring) countries, they could be tolerated. Indeed, HTS in Syria is ruling a small emirate in the Idlib’s governorate and the Taliban is ruling Afghanistan. Though they do not enjoy international recognition, they may provide a more sustainable model for jihadism. It must be noted, though, that the inferior status of these two unrecognized regimes, and in general jihadi actors’ inability to accept the state-based order as legitimate, make even their success uncertain. HTS’ emirate is in a particularly perilous position, controlling only a small part of Syria, lacking international recognition of its statelet, and susceptible to collapse without Turkey’s backing.59 The Taliban’s situation is somewhat better; the international community’s rejection of the Taliban makes its rule more difficult and essentially invites internal challengers to confront the regime,60 but the state they control, Afghanistan, has long enjoyed international recognition.

Jihadis may also go bigger, aiming for regional emirates, especially in areas where the state has failed to put down strong roots and areas of limited strategic importance for the great powers. Jihadis are more likely to succeed where the power of nationalism is low, and where the state is essentially a quasi-state,61 demonstrating many of the symbolic trappings of a state, yet internally hollow with very little capacity to service their citizens. Africa, then, appears the most promising location for jihadi success. In Africa, jihadis are demonstrating their ability to take advantage of inter-ethnic or inter-tribe conflicts to gain power. Their Islamist message offers the public a set of beliefs and ideas to unite around when national identity fails. Jihadis may also link themselves with some tribes to capture the state and impose their views through their ally ethnic group. Reflecting increased worries about jihadi activities in Africa, the most recent U.N. report tracking the jihadi global terror threat stated: “In West Africa and the Sahel, violence and threat have escalated again, and the dynamics have become yet more complex. Some Member States are concerned that greater integration of terrorist groups in the region, and freedom of manoeuvre, raises the risk of a safe operating base developing from which they could project threat further, with implications for regional stability.”62

But jihadi efforts to take advantage of local cleavages could also backfire. Jihadis may end up being identified with a particular tribe or ethnic group, and generate opposition from other ethnic groups and tribes.63 Jihadis might also find their struggle hijacked by non-religious interests.c

Looking Ahead

The war in Gaza, following Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel, has increased concerns about a resurgence of jihadi terrorism, especially in the West.64 It is certainly a “galvanising cause” for transnational jihadis,65 and one al-Qa`ida has already used to support its old narrative about the need to center the fight against the United States as Israel’s sponsor, and about the betrayal of the Arab regimes, which requires pious Muslims to step in and assume their ‘Islamic’ responsibilities.66 There is little doubt that the war has already radicalized some Muslims. There has been an uptick in lone wolf attacks by jihadis,67 and the war will likely boost recruitment to jihadi groups (especially to those groups who could persuasively link their work to the plight of Palestinians).However, one must not exaggerate the likely impact of the Gaza war on the jihadi scene. For one, relations between jihadi groups and Hamas (associated with the Muslim Brotherhood strand within Islam) have been shaky at best, and at times hostile.68 Second, as Tricia Bacon argues, the current lack of compelling leaders within the jihadi movement undercuts their ability to take advantage of the emerging new opportunities.69 Third, although the war clearly upsets the Muslim street, at least among the rich Gulf states social and economic reforms, alongside efforts to counter the jihadi narrative, constrain jihadis’ ability to take advantage of the public outrage.

At the bottom line, though the jihadi movement is resilient, it is also weak. Although its end is not in sight, the movement’s prospects of success are dim and the war in Gaza is highly unlikely to change that. In the West, the jihadi threat is real, but small. It often reflects societal problems of integration, inequality, and racism, clothed in a radical Islamist discourse. The threat is focused on terrorist attacks (mostly by lone wolves or small-scale directed attacks) that may cost lives, but would have little strategic impact, at least as long as the attack’s target avoids overreaction that would turn, unnecessarily, a tactical jihadi success into a strategic event. Otherwise, jihadism’s impact on developed countries is mostly indirect, usually taking the form of waves of migrants escaping war zones and jihadi brutality for the safety and economic potential of the West.

In the Muslim world, the picture is more complex: After attempts to overthrow the regimes of more established Muslim states (such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Algeria) failed, the main jihadi threat is in the Muslim periphery, primarily in Africa. Conflicts in such locations tend to be so muddled, with numerous actors complicating the fight,70 that external intervention by the West becomes less likely. And when it does take place, the interveners’ staying power is limited, as it often becomes clear that staying the course is unlikely to produce success but, rather, lead the intervener into a quagmire. For example, France abandoned its missions in Mali and Burkina Faso after seeing its influence waning and the likelihood of bringing stability to the region greatly diminished by military coups in its partner states and the hiring of Wagner mercenaries, notorious for human rights violations.71

The Sahel may also be the harbinger of a new jihadi strategy that is regionally focused, as different jihadi groups are gradually coalescing into one large arena encompassing Mali, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Togo, and Nigeria. Operating from different directions and taking advantage of the weak institutionalization of the region’s states and porous borders, jihadis of al-Qa`ida and Islamic State branches may slowly connect the different arenas and advance toward the Atlantic coast. But there is an important caveat: Such a regional model might work only in regions with low strategic significance for the great powers and while the international community is preoccupied elsewhere. Moreover, the durability of the jihadis’ success is in doubt: jihadi actors might thrive in chaos, but their ultimate objective is the production of a jihadi order and they are far from being able to achieve it.

Additionally, it is not clear to what extent jihadi organizations in Africa reflect jihadi beliefs and goals. Often jihadism is superimposed on local cleavages (ethnic, clans).72 In some cases, local actors would turn to jihadi discourse as a way to gain public support, donations from rich Muslim donors, support from existing jihadi groups, volunteers, and moral authority. For example, the successful al-Qa`ida Sahelian sub-branch, JNIM, is currently led by Iyad Ag Ghaly, a Tuareg politician turned jihadi, and Amadou Koufa, a Fulani, not well credentialed jihadis, but latecomers to jihad. One may wonder whether a successful establishment of an emirate in Mali would present the world with a jihadi state, or, as this author finds more likely, ethnic-based government in jihadi clothes that could be stripped of its extreme religious commitments for political recognition and external aid. The needs of these war-torn countries suggest that any sustainable success would require the emerging jihadi ruling class to abandon jihadism and seek their country’s re-incorporation into the society of states.

The regional model of jihadi activity is also compatible with fighting the ‘near enemy.’ After all, the regional model assumes a region in which states suffer from severe control problems. To some extent, the regional model is built on bringing together local jihads. However, if in the past jihadis tried to topple strong regimes in the heart of the Middle East, the new local jihads take place in countries that suffer from severe control problems. This also means these struggles are less likely to be based on urban terrorism, and more on guerrilla tactics.

Although the jihadi brand name makes it unlikely that the international community would offer external recognition to a jihadi state (especially if the successful jihadi group were affiliated with al-Qaida or the Islamic State), in some cases jihadi groups could still run a country or an entity resembling a state, the way HTS is ruling Syria’s Idlib governorate.73 However, such jihadi rule remains at the mercy of state actors. Jihadis’ foray into governance may ease their acceptance by the international community: bothered with the provision of daily public service, groups will have fewer resources to dedicate to expansion and violence. Moreover, by providing services, perhaps even through cooperative enterprises with foreign NGOs, ruling groups could demonstrate to the international community that they are ready to become responsible actors within the state-based order. Jihadi entities may also demonstrate their ability to contribute to international order by taking steps against al-Qaida and the Islamic State, as HTS has been doing in recent years.d

And here lies the ultimate dilemma for the jihadi movement: the closer it gets to attaining political objectives, the greater the pressure it would face to conform to ‘normal’ politics and abandon much of what makes it a jihadi movement.

This dilemma also requires the United States to reconsider its approach to jihadi success. Painful as the 9/11 attack was, American overreaction helped the expansion of the jihadi movement. The United States has learned some important lessons since. It understands not only the need to keep an eye and prevent, when possible, the emergence of jihadi safe havens, but also how its own actions may enhance the appeal of jihadism. Consequently, although in principle the United States rejects all jihadi groups, in practice it has tolerated some form of jihadi rule. In this manner, the United States has revealed that it learned to make distinctions between (and within) jihadi groups and arenas, as well as its greater proclivity for more nuanced response to dissimilar jihadi threats.

The current decline of the major transnational jihadi groups may lead the United States to reduce its attention to the jihadi threat. This would be a mistake. Instead, the United States and its international allies should take advantage of the opportunity to refine their strategy to dealing with the jihadi movement while tensions are still relatively low and political considerations less weighty. It should embrace that opportunity. The jihadi movement is still here, it is still dangerous, and it is going nowhere. The United States and the international community should be ready for this reality.

Substantive Notes

[a] Editor’s Note: This article is the second in a new recurring series in CTC Sentinel entitled “On the Horizon” that examines emerging counterterrorism challenges and long-term developments.

Citations

[1] Daniele Garofalo, “Islamic State Announces New Leader and Spokesman,” Daniele Garofalo Monitor, August 5, 2023.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News