The EU should go into the military economy, said the head of the European Council Charles Michel. It is expected that at the summit on March 21-22, the heads of state of the EU members will agree on joint purchases of weapons, increase the military budgets of countries and accelerating the supply of shells to Kiev. Despite the fact that the Russian army seems hopelessly oust in Ukraine, European politicians and the military are seriously afraid that in the very near future Vladimir Putin will unleash a new conflict, fraught with war against one of the European members of NATO, that is, in fact, against almost the whole of Europe. There is every reason for concern: the number of European armed forces has decreased significantly after the Cold War, weapons have also become less, and all the Bundeswehr shells will be enough for a maximum of two days of hostilities. Europeans, who have long relied on U.S. support, have to dramatically increase military spending, especially against the backdrop of statements by US presidential candidate Donald Trump, threatening to withdraw from NATO.

Europe is waiting for war

At the beginning of the year, the Commander-in-Chief of the Swedish Armed Forces, Mikael Büden, called on citizens to “be prepared for war,” and the Minister of Civil Defense, Karl-Oskar Bohlin, directly linked the military threat to Vladimir Putin’s actions in Ukraine. When discussion of this issue reached TikTok, psychological helplines in Sweden were bombarded by worried children and teenagers.

This was followed by alarmist statements from European politicians and military personnel regarding the impending war.

German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius said that it is necessary to prepare for the fact that Vladimir Putin one day decides to attack one of the NATO countries.

The Chief of the Defense Staff (General Staff) of the Romanian Armed Forces, Lieutenant General Gheorghita Vlad, predicted an inevitable military escalation in Moldova if the Russian army achieves success in Ukraine, and also predicted an increase in instability in the Balkans.

British Chief of the General Staff General Patrick Sanders called for “mobilizing the nation” in the face of the Russian threat. As a result, the government had to issue a separate clarification that this was about a “turn in public consciousness,” and not about plans to return to conscription.

British Chief of the General Staff General Patrick Sanders called for “mobilizing the nation” in the face of the Russian threat

Opinions differ on the timing of the Russian attack. The German publication BILD has published what it claims is a secret Bundeswehr document describing a likely war scenario between Russia and NATO. According to the material, a direct collision in the Baltic countries and the Suwalki corridor region is possible as early as the summer of 2025. True, for this to happen, the Kremlin will need, as a precondition, to carry out a new mobilization and achieve decisive success on the front in Ukraine this summer.

The British tabloid Daily Mail, in turn, pleased readers with a futuristic forecast of a hybrid attack on Europe in cyberspace, on land, on water and in the air in 2044, mentioning in particular Russian “tanks under the control of artificial intelligence” and special forces that will begin the invasion.

Between these two extremes – war in a year or in 20 years – lies most of the forecasts, which are somewhat more authoritative than the fantasies of the yellow press. Experts agree that it will take 6 to 10 years to restore the combat capability of the Russian Armed Forces to a level sufficient for at least a limited conflict with NATO. Boris Pistorius mentioned above gives a range of 5 to 8 years. Danish Defense Minister Troels Lund Poulsen is leaning towards 3–5 years, while the commander of the Norwegian army, General Eirik Kristoffersen, is based on 2–3 years in reserve.

Adding fuel to the fire are the scandalous statements of US Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump that he will encourage Russia to take aggressive action (literally “do whatever the hell it wants”) against those NATO countries that do not spend enough funds for defense, that is, less than 2% of GDP. Back in 2020, President Trump told the head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, that he would not come to the aid of Europe in case of war, would leave NATO, and at the same time asked to “repay the debt” of $400 billion that the Germans “saved” on defense spending.

Donald Trump’s scandalous statements that he will encourage Russia to take aggressive actions add fuel to the fire.

At the recently concluded Munich Security Conference, the general consensus was more or less that the post-1991 order was not only being challenged, but had ceased to exist. It is unclear what the new one will be, because if last year the event was held under the auspices of transatlantic unity in terms of unconditional support for Ukraine in the war, now the mood of the participants is characterized primarily by uncertainty.

As Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk wrote , the “post-war era” gave way to the “pre-war era,” apparently drawing parallels with the time before the outbreak of World War II. The current state of affairs in international relations really resembles the second half of the 1930s: as then, the world is faced with simultaneous major crises in different regions (then the expansion of Germany with its allies in Europe and Africa, the Japanese invasion of China, today the wars in Ukraine and in the Middle East), while institutions designed to ensure stability have proven completely ineffective (then the League of Nations, today the UN).

According to Ursula von der Leyen, war in Europe is unlikely to break out any time soon, but it no longer seems impossible. The key question that experts and journalists are asking is this : is Europe ready to defend itself from Russian aggression without US help?

Scholz, Macron, where are the shells?

Over the past 30 years, European countries have seriously reduced military spending, the size of their armies, massively abandoned compulsory conscription, sent for scrap metal or sold gigantic amounts of military equipment and weapons to third countries. The end of the Cold War allowed for the release of enormous resources: all armies of the world (not just European ones) experienced similar processes of reduction in numbers and reorientation towards counterinsurgency and humanitarian missions, since the likelihood of a major war was considered negligible.

According to McKinsey , Europeans saved between $1.6 trillion on defense between 1992 and 2022 (based on the NATO minimum of 2% of GDP) to $8.6 trillion (based on average spending since 1960). to 1992). In its most general form, this is usually called a “peace dividend” – when expenses previously spent on the defense sector are reduced and redirected to other needs, for example, to the development of healthcare and education.

For Germany, which at the end of the 1980s had the most powerful army in Europe, the figure for underfunding of defense is estimated at €394 billion. It is not surprising that in some areas, in particular in digitalization and the development of secure communications systems, the Bundeswehr remained at the level of 30 years prescription It’s hard to believe, but they still use faxes to transmit orders and keep paper documents.

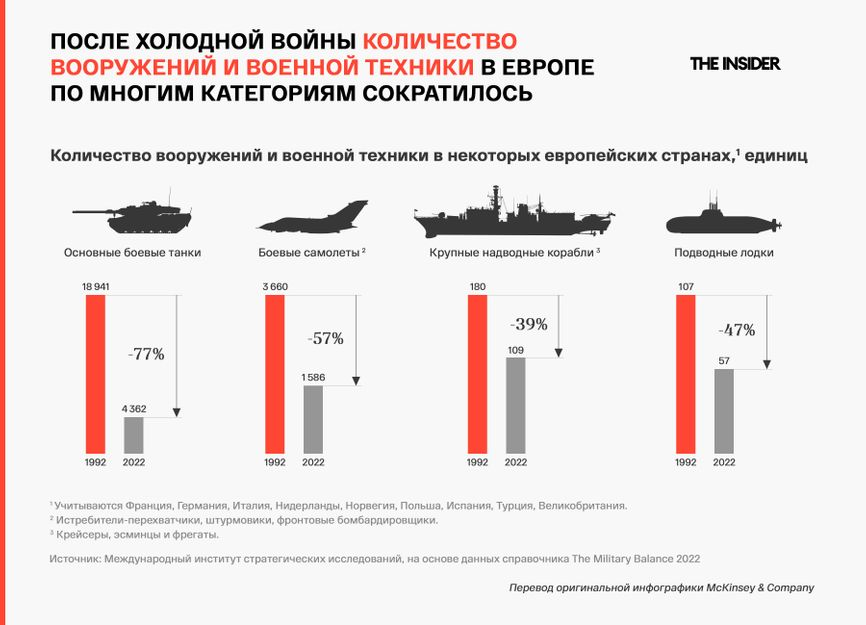

The size and equipment of the European armed forces in certain categories of military branches and types of military equipment has decreased several times over the 30 years from 1992 to 2022. Decommissioned models were replaced by more expensive and efficient, but much less widespread (“small-scale”) platforms. In particular, the number of tanks in service with the leading countries (Germany, France, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain and Turkey) decreased from 18,941 to 4,362 units, fighters – from 3,660 to 1,586 units, large surface ships – from 180 up to 109 units, submarines – from 107 to 57 units.

These two processes – the decommissioning of Cold War-era equipment and its gradual replacement with custom high-tech units – in combination have led to the fact that the armed forces as a whole are still dominated by outdated weapons. For the ground forces in Europe, about 50% of the available equipment was commissioned before 1990 or is based on technologies and solutions developed then, for the Air Force – about 35%, for the Navy – about 40-50%. In addition, even the available equipment was not maintained in proper condition: just remember the episode when, before sending six Spanish Leopard 2 tanks to Ukraine, it was necessary to spend millions of euros and several months on their repairs. This results in rather modest indicators of the combat readiness of existing military equipment and weapons.

The reductions also affected the size of the armed forces. In 1991, almost 1 million military personnel were stationed in Central and Northern Europe alone . By the end of the 2010s, their number decreased by 2.5 times. Today, the total number of armed forces of NATO member countries in Europe is slightly less than 2 million people – however, 460 thousand of them are in Turkey, and in continental Europe itself, France has the largest army, and this is only 200 thousand people.

As a result, the term bonsai armies , that is, miniature copies of real armies, is often used in relation to European armies. This approach was logical within the framework of a concept that assigns to the armed forces only a supporting role of deterrence at the initial stage in the event of a major war. US intervention would then follow.

The huge European military-industrial complex has also been consistently shrinking since 1990, having actually lost some of its most important competencies. For example, since 2008, in Europe there was essentially the only production line left for the production of modern main battle tanks – the German Leopard 2. As of February 2023, the production capacities of all EU countries could produce an estimated only 230 thousand artillery ammunition per year – this is about a month volume of consumption during the war in Ukraine. France today is capable of producing only 2 thousand artillery rounds per month and only plans to increase the production volume to 3 thousand units. On the scale of the current war in Ukraine, this will be enough for one day of combat operations with maximum savings in ammunition.

The huge European military-industrial complex has been consistently shrinking since 1990, losing some of its most important competencies.

It is not surprising that the EU countries were unable to fulfill their promise to supply 1 million artillery ammunition to the Ukrainian Armed Forces by March 2024. For almost two years of war, they managed to send only 300 thousand 155 mm shells. According to some estimates , on peak days in terms of the intensity of artillery fire during the offensive in the Donbass in the summer of 2022, the Russian Armed Forces used more artillery ammunition than all available stocks in the British Army’s warehouses. The Bundeswehr probably only has enough ammunition for two days of fighting.

The Bundeswehr probably only has enough ammunition for two days of fighting.

Is Europe ready for war?

Even after the invasion of Ukraine, NATO countries (not including the US) increased their total defense spending by just 2% in 2022 and by 8.3% in 2023 (both estimates). Only 11 countries out of 31 participants meet the requirement to spend at least 2% of GDP on defense (at constant 2015 prices). In Germany, back in February 2022, they announced a radical revision of the defense construction policy, but €100 billion has not yet been allocated for the modernization of the armed forces. German defense spending in 2023 is estimated at just 1.2% of GDP.

Today, Europe is most likely not capable of waging a classic conventional war, which requires gigantic amounts of equipment and ammunition. Without the United States, European countries find themselves in a vulnerable position in the event of an unconventional, that is, nuclear conflict. European nuclear powers France and Great Britain have only 500 warheads between them – 10 times less than the Russian arsenal.

On the other hand, historically, French nuclear doctrine was based not on the use of a limited number of special ammunition directly on the battlefield, but on the threat of attacks on Soviet cities, which was supposed to convince the leadership of the USSR not to attack French territory. However, natural questions arise as to how applicable this strategy is to the protection of not only French, but also “pan-European” interests: The Economist magazine, discussing the European nuclear doctrine, rhetorically asks whether President Emmanuel Macron is ready to “exchange Toulouse for Tallinn.”

Defense policy reversal

It cannot be said that Europe does not realize the seriousness of the current situation. Before our eyes, long-term trends are being broken: industrial war has returned to the European continent, a large-scale conflict with Russia has turned from a hypothetical threat into a highly probable one, NATO has finally acquired a new meaning after the disappearance of the enemy in the person of the Warsaw Pact Organization.

In June 2022, the Alliance’s strategic concept identified Russia for the first time as the most significant and direct threat. In 2024, according to forecasts , the total military spending of European NATO members on average will reach exactly 2% of GDP ($380 billion).

For the first time, Russia was identified as the most significant and direct threat to NATO

According to McKinsey , the total increase in military budgets in Europe for the period from 2022 to 2028 will be $700–800 billion. The volume of orders from the seven largest European defense concerns reached $300 billion at the end of 2023. By 2025, the volume of production of artillery ammunition is expected caliber 155 mm will grow to 1.25 million per year.

The European Commission presented the first defense strategy in the history of the organization. According to the draft document, until 2030, EU states will spend at least half of their military spending on intra-member procurement, and by 2035 this figure should increase to 60%. It is also planned to carry out at least 40% of defense procurement on a collective basis by 2030.

But the size of the military, the health of military equipment and the level of defense spending are not the only variables to consider. Equally (if not more) important in the event of a full-scale conflict will be the sustainability of critical infrastructure, including digital infrastructure, and the readiness of the transport network and population. In addition, on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference, the creation of a kind of “European dimension of NATO” was discussed in case the United States really abandoned its defense obligations.

How likely is conflict in Europe?

As long as the Russian army is fighting against Ukraine, the likelihood of a new conflict, especially with a NATO country, seems insignificant. Meanwhile, some experts and politicians from the West proceed from the following premise : Russian ground forces actually suffered significant damage during the war against Ukraine, but the air and naval forces retain significant combat potential, not to mention a gigantic nuclear arsenal.

The Kremlin’s largely uncritical claims about unprecedented growth in production in the defense sector and record levels of volunteer recruitment add to the picture of the threat looming over Europe. In particular, we are talking about the production of 4 million artillery ammunition per year and the involvement of 400 thousand contract soldiers even without mobilization.

At the same time, European countries have significantly depleted their arsenals, transferring a lot of equipment not only from storage, but directly from the availability of national armed forces. According to the head of the Rheinmetall concern, Armin Papperger, it will take Europe 10 years to restore reserves to the level they had before the start of the war in Ukraine, and this, of course, can be seen in Moscow as a kind of “window of opportunity”, especially in the case if the United States is somehow made to doubt its willingness to stand up for its European allies.

It will take Europe 10 years to restore supplies to the level they had before the war in Ukraine.

Possible scenarios for a future conflict include:

an attempt to attack the Suwalki corridor, separating the Kaliningrad region of the Russian Federation from the territory of Belarus;

an attack (not necessarily purely military, hybrid options are also possible) on one of the Baltic countries in order to test the Alliance’s readiness to challenge one of the two largest nuclear powers (here a comparison is appropriate with the popular slogan in France before the start of the previous world war, “Why die for Danzig? “);

attack or provocation on the border with Finland (say, the threat of an artificial influx of migrants).

The likelihood of one of these scenarios being realized is increased by uncertainty regarding long-term financing for Ukraine, as well as doubts about the preservation of Euro-Atlantic unity if Donald Trump comes to power in the United States.

Since 2014, the Kremlin has consistently raised the stakes in its confrontational foreign policy: it annexed Crimea and invaded the Donbass, began to intervene in the civil war in Syria and actively move closer to Iran, finally launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine and finally integrated itself into the “axis of evil” with Iran and DPRK. In this context, an attack on one of the NATO countries seems very logical if the Kremlin expects that Brussels will consider the negotiation process more preferable than a war with the prospect of an exchange of nuclear strikes.

However, everything is not so rosy in the Russian economy, and so far time is working against it. In addition, the analysis shows that the figures for the incredible increase in defense production in Russia are many times overestimated. At least, significant growth in the military-industrial complex is not recorded by indirect data on the production of chemical products, metals, electricity consumption, loading on the railway network, and so on. There will probably be an increase, but not exponentially.

The total defense budget of NATO countries in 2023 is estimated at $1.1 trillion, even excluding the United States this is $356 billion. For the European members of the Alliance, the total defense budget for 2023 is $347 billion, for 2024 – $380 billion. This is twice as much as the Russian military expenditures in 2023, which amounted (estimated, since they are now mostly classified) to at least 13.4 trillion rubles (at current exchange rates – about $150 billion). In 2019–2021, 3.0–3.6 trillion rubles were spent on defense, in 2022 – 8.4 trillion rubles. Even more is planned for 2024 – 14.7 trillion rubles (at the current exchange rate – about $160 billion).

Keeping military spending at more than 40% of all federal budget expenditures and 6% of national GDP for any length of time seems extremely unlikely. In fact, Putin himself openly says that the West will not be able to “repeat the trick of the 1980s” and drag Russia into an arms race.

It will be difficult for Russia to keep military spending at a level of more than 40% of the budget and 6% of national GDP for a long time

As for the Russian Armed Forces itself, some experts, for example, Pavel Luzin, a visiting fellow at the Fletcher School of Tufts University (USA), are inclined to believe that Putin’s military machine is experiencing organizational and logistical degradation. According to some estimates , Russia will reach the peak of its military capabilities in 2024–2025. Accordingly, if the Ukrainian Armed Forces, with the help of their allies, survive, then this will be followed by a long-term change in the balance of power: the Russian side will largely exhaust its ability to remove equipment from storage, but in the West, on the contrary, the production of new equipment and ammunition should reach significant volumes.

In other words, all this does not indicate an increase in Russia’s military potential, but rather its depletion. Of course, this does not mean at all that the Kremlin will not decide on a new military conflict in Europe (the very fact of aggression against Ukraine proves that nothing can be ruled out), but there are few objective prerequisites for this, and the likelihood of achieving any foreign policy goals in this way is even less.

And the key question here is the outcome of the current Russian-Ukrainian war. Most likely, new “special operations” in Central and Eastern Europe will only become a reality if the Kremlin is decisively successful in Ukraine. And such an outcome seems likely only if Kyiv’s allies fail to provide military support at the proper level. If the Ukrainian Armed Forces survive in 2024, then the Russian side will have to go on the defensive, when there can be no talk of any new military operations.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News