Yemen’s Red Sea naval operations have drawn attention to Iran’s own strategic calculations for this vital maritime corridor, most of them driven by Tehran’s valid security and economic interests.

The Red Sea has been a crucial historical nexus for Iran, with its roots tracing back to ancient times when the Achaemenid Empire extended its influence along its shores. Over the centuries, from the Sassanid era to contemporary times, Iran’s connection with this strategic waterway has evolved and deepened, most notably through its ties with Yemen.

While, in the modern era, the Indian Ocean, Horn of Africa, and the Red Sea grew in strategic value under the pre-revolutionary reign of Mohammad Reza Shah, it is in recent decades that Tehran has made concerted efforts to forge multifaceted ties with Red Sea states, excluding Israel.

Under former Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, cooperation blossomed in counterterrorism, arms control, and military technology, and Tehran made a strategic decision to extend its operational theaters into new waterways further afield.

‘We’re securing these waterways’

It’s been a shocking development for Washington – which views Iran as its key adversary in West Asia – to watch its nemesis’ navy and commercial vessels swan into the various gulfs, straits, seas, and oceans once under US domain.

The Iranians have taken a page out of the American playbook: where the Pentagon goes to “thwart terrorism and piracy,” “police the seas,” and secure its maritime borders, so too does Iran, with even more credibility, because these waterways are its actual backyard.

As Dr Sadollah Zarei, director of the Tehran-based Andisheh Sazan Noor Institute, said in 2017, “US actions give us a behavior precedent in our naval reach.” The US naval presence in Iran’s neighboring waters “gives us even more right to be active in the Persian Gulf, in the Gulf of Aden, and other waters.” As a result, Zarei explained, “We are now in the Gulf of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.”

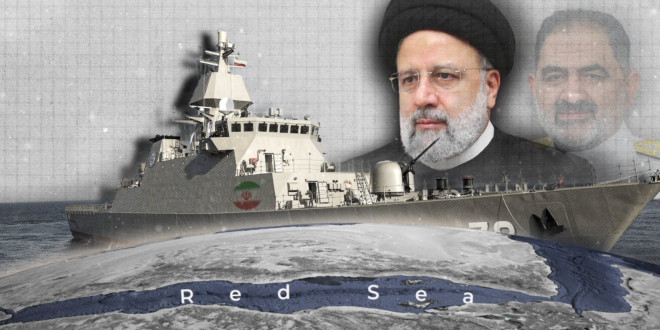

The turn of the millennium marked Iran’s heightened engagement in the Red Sea region, but post-2016, diplomatic ties frayed with several Red Sea countries, chiefly Saudi Arabia. Now, under Ebrahim Raisi’s presidency, this critical waterway is under renewed foreign policy focus.

The Red Sea is located between the Arabian Peninsula and northeastern Africa, the Bab al-Mandab strait, the Indian Ocean, and the Suez Canal. Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Jordan, and Israel are the neighbors of the Red Sea.

After the Beijing-brokered restoration of relations with Saudi Arabia last year, a November meeting between Iran’s Raisi and Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Riyadh and a telephone conversation between the two at the end of December have accelerated Tehran’s normalization efforts with Cairo.

Additionally, the recent successful restoration of mutual relations between Sudan and Iran after a seven-year hiatus marks another significant diplomatic achievement.

Pivot to Africa

Iran’s strategic pivot towards Africa, particularly the Red Sea, is intentional. Raisi’s historic three-nation Africa tour last year underscores Tehran’s ambitions to bolster its regional standing and marked the first visit by an Iranian president to the continent in 11 years.

Furthermore, his recent trip to Algeria earlier this month was the first of its kind to the North African country in 14 years.

Clearly, it is diplomacy and economy – not conflict – on Iran’s agenda as it actively seeks to counter US influence and mitigate western sanctions by engaging beyond West Asia.

From Tehran’s perspective, the emerging multipolar world order is defined by a series of coalitions, each vying for influence. In this context, the Red Sea holds immense geopolitical and geostrategic significance, attracting attention from both regional and extra-regional actors such as Russia, the UAE, China, and the US.

For instance, in Russia’s 2023 Foreign Policy Concept, Moscow prioritized the establishment of a multipolar international system and engagement with Africa.

Iran, now a member of BRICS+ and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), recognizes the shifting global dynamics and sees potential in trilateral cooperation among Moscow, Tehran, and Beijing to counterbalance Washington’s geopolitical influence in the region.

Over the years, western states and their regional allies have actively sought to create geopolitical challenges and isolate Iran – notably, Israel, which remains a formidable adversary along the Red Sea coast. To counter such threats, Iran has consistently aimed to neutralize hostile actions against it by increasing its geopolitical weight in this region.

Iran has, therefore, strategically focused attention on bolstering its influence in the vicinity of the Red Sea’s critical waterways. The emergence of the Ansarallah-led, de-facto government in Yemen provided an opportune moment for Tehran to deepen its influence in the region.

Another rationale for Iran’s expanding presence in the Red Sea is the region’s significant economic and geo-economic potential. With its abundant primary resources and growing consumer market, Africa presents a promising partnership opportunity for Tehran.

Aiming to boost trade with Africa tenfold, Iran is formulating strategies to enhance economic and trade ties with African states, aligning its focus with economic and geo-economic objectives to bolster its national power.

Last summer, President Raisi acknowledged that Iran’s share of the African economy “is very low.”

Apart from supporting Palestine, the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran defends the values of the Islamic Revolution by strengthening internal independence and confronting the domination of domineering countries.

In light of this, Iran also seeks to expand its soft power by increasing its presence in the Red Sea.

Expanding Iran’s strategic depth

According to Iranian policymakers, security is an interconnected concept, and the security of the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea are related.

On 3 January, Iran’s Permanent Representative to the UN pointed out Iran’s importance to maritime security and freedom of navigation, noted in a letter to Antonio Guterres, the Secretary General of the UN, and the French Ambassador to the UN, who holds the rotating presidency of the Security Council:

America cannot deny or cover up this undeniable fact: The fact that the recent events in the Red Sea are directly related to the continuation of Israeli crimes against the Palestinian people in Gaza.

In January, Iran’s foreign minister criticized the US for its efforts to militarize the Red Sea. In response to Washington’s plan to form a naval alliance in the Red Sea, Iranian Defense Minister Mohammad Reza Ashtiani said on 17 December: “The Red Sea is considered Iran’s territory, and no one can maneuver.”

In early March, Major General Yahya Rahim Safavi, a former chief commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC), said, “The depth of our strategic defense is the Mediterranean Sea.” He added, “We should expand our strategic [defense] depth by 5,000 kilometers (3,106 miles).” Safavi also described the Mediterranean and Red Seas as “strategic spots.”

The US and its allies have sought to justify their imposition in the Red Sea due to Tehran’s support for Sanaa. While the Iranians have repeatedly denied involvement in the Ansarallah Red Sea operations, the Islamic Republic considers the waterway as a legitimate field for resisting Israeli aggression and supports pressuring Tel Aviv to halt its genocidal war on Gaza via these operations.

In addition, due to Iran’s technological power and the innovation and development of effective and smart weapons, Iran will have the possibility of establishing a naval base in the Red Sea and sending weapons to African countries and the region through the Red Sea.

Raisi’s Red Sea policy

Although Iran’s future approach to the Red Sea is subject to numerous political, economic, international, and security considerations, factors such as economic sanctions and the responses of other powers also hold significance.

Yet, shifts in US policy in West Asia, dwindling global interests, geopolitical changes, and a trend towards pragmatic policies will remain pivotal variables for Tehran’s strategic focus on the Red Sea. Iran’s overarching goal is to resolve conflicts, normalize diplomatic relations, and broaden cooperation with Red Sea countries across various domains.

Tehran prioritizes enhancing or broadening ties with Red Sea-bordering states, excluding Israel, while strategically leveraging the Red Sea as a geopolitical asset. Iran’s active presence serves the dual purpose of safeguarding international waterways and maritime traffic, combating piracy, and preparing to counter both official and unofficial threats and conspiracies, including the escort of commercial ships, oil tankers, and fishing vessels.

Iran is poised to expand its sphere of influence, foster intelligence cooperation among Red Sea littoral states, and potentially pursue regional security collaboration, including the establishment of a naval alliance with friendly states in the region.

The Red Sea, viewed as a gateway to international trade and Africa, offers Iran an alternative route to circumvent sanctions. As such, Iran may intensify its presence in the Red Sea’s free zones and invest in energy, oil, electricity, infrastructure, and port development.

Additionally, as an official member of BRICS, Tehran may seek to maximize its economic influence by bolstering the North–South international corridor, enhancing banking cooperation, promoting the use of national currencies, and increasing Iranian exports. Such initiatives would be carefully aligned with the interests of regional stakeholders.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News